Edsger Wybe Dijkstra (1930–2002): a Portrait of a Genius Krzysztof R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Software Development Career Pathway

Career Exploration Guide Software Development Career Pathway Information Technology Career Cluster For more information about NYC Career and Technical Education, visit: www.cte.nyc Summer 2018 Getting Started What is software? What Types of Software Can You Develop? Computers and other smart devices are made up of Software includes operating systems—like Windows, Web applications are websites that allow users to contact management system, and PeopleSoft, a hardware and software. Hardware includes all of the Apple, and Google Android—and the applications check email, share documents, and shop online, human resources information system. physical parts of a device, like the power supply, that run on them— like word processors and games. among other things. Users access them with a Mobile applications are programs that can be data storage, and microprocessors. Software contains Software applications can be run directly from a connection to the Internet through a web browser accessed directly through mobile devices like smart instructions that are stored and run by the hardware. device or through a connection to the Internet. like Firefox, Chrome, or Safari. Web browsers are phones and tablets. Many mobile applications have Other names for software are programs or applications. the platforms people use to find, retrieve, and web-based counterparts. display information online. Web browsers are applications too. Desktop applications are programs that are stored on and accessed from a computer or laptop, like Enterprise software are off-the-shelf applications What is Software Development? word processors and spreadsheets. that are customized to the needs of businesses. Popular examples include Salesforce, a customer Software development is the design and creation of Quality Testers test the application to make sure software and is usually done by a team of people. -

Chapter 1: Introduction What Is an Operating System?

Chapter 1: Introduction What is an Operating System? Mainframe Systems Desktop Systems Multiprocessor Systems Distributed Systems Clustered System Real -Time Systems Handheld Systems Computing Environments Operating System Concepts 1.1 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne 2002 What is an Operating System? A program that acts as an intermediary between a user of a computer and the computer hardware. Operating system goals: ) Execute user programs and make solving user problems easier. ) Make the computer system convenient to use. Use the computer hardware in an efficient manner. Operating System Concepts 1.2 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne 2002 1 Computer System Components 1. Hardware – provides basic computing resources (CPU, memory, I/O devices). 2. Operating system – controls and coordinates the use of the hardware among the various application programs for the various users. 3. Applications programs – define the ways in which the system resources are used to solve the computing problems of the users (compilers, database systems, video games, business programs). 4. Users (people, machines, other computers). Operating System Concepts 1.3 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne 2002 Abstract View of System Components Operating System Concepts 1.4 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne 2002 2 Operating System Definitions Resource allocator – manages and allocates resources. Control program – controls the execution of user programs and operations of I/O devices . Kernel – the one program running at all times (all else being application programs). -

Computing Versus Human Thinking

By Peter Naur, recipient of ACM’s 2005 A.M. Turing Award Computing Versus Human Thinking n this presentation I shall give you an overview of efforts. Indeed, I have found that a large part of what Imy works from the past fifty years concerning the is currently said about human thinking and about sci- issue given in the title. Concerning this title I entific and scholarly activity is false and harmful to invite you to note particularly the middle word, ‘ver- our understanding. I realize that my presentation of sus’. This word points to the tendency of my efforts some of these issues may be offensive to you. This I around this theme, to wit, to clarify the contrast regret, but it cannot be avoided. between the two items, computing and human thinking. This tendency of my work has found its DESCRIPTION AS THE CORE ISSUE OF SCIENCE AND ultimate fulfilment in my latest result, which is a SCHOLARSHIP description of the nervous system showing that this The tone of critique and rejection of established system has no similarity whatever to a computer. ideas has its roots in my earliest activity, from its very It is ironic that my present award lecture is given beginning more than fifty years ago. Already in my under the title of Turing. As a matter of fact, one part work in astronomy, around 1955, a decisive item in of my work concerning computing and human think- my awareness came from Bertrand Russell’s explicit ing has been an explicit critique, or rejection, of the rejection of any notion of cause as a central issue of ideas of one prominent contribution from Alan Tur- scientific work. -

A Politico-Social History of Algolt (With a Chronology in the Form of a Log Book)

A Politico-Social History of Algolt (With a Chronology in the Form of a Log Book) R. w. BEMER Introduction This is an admittedly fragmentary chronicle of events in the develop ment of the algorithmic language ALGOL. Nevertheless, it seems perti nent, while we await the advent of a technical and conceptual history, to outline the matrix of forces which shaped that history in a political and social sense. Perhaps the author's role is only that of recorder of visible events, rather than the complex interplay of ideas which have made ALGOL the force it is in the computational world. It is true, as Professor Ershov stated in his review of a draft of the present work, that "the reading of this history, rich in curious details, nevertheless does not enable the beginner to understand why ALGOL, with a history that would seem more disappointing than triumphant, changed the face of current programming". I can only state that the time scale and my own lesser competence do not allow the tracing of conceptual development in requisite detail. Books are sure to follow in this area, particularly one by Knuth. A further defect in the present work is the relatively lesser availability of European input to the log, although I could claim better access than many in the U.S.A. This is regrettable in view of the relatively stronger support given to ALGOL in Europe. Perhaps this calmer acceptance had the effect of reducing the number of significant entries for a log such as this. Following a brief view of the pattern of events come the entries of the chronology, or log, numbered for reference in the text. -

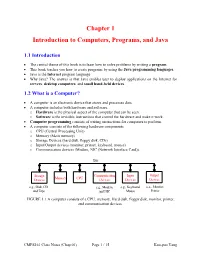

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java 1.1 Introduction • The central theme of this book is to learn how to solve problems by writing a program . • This book teaches you how to create programs by using the Java programming languages . • Java is the Internet program language • Why Java? The answer is that Java enables user to deploy applications on the Internet for servers , desktop computers , and small hand-held devices . 1.2 What is a Computer? • A computer is an electronic device that stores and processes data. • A computer includes both hardware and software. o Hardware is the physical aspect of the computer that can be seen. o Software is the invisible instructions that control the hardware and make it work. • Computer programming consists of writing instructions for computers to perform. • A computer consists of the following hardware components o CPU (Central Processing Unit) o Memory (Main memory) o Storage Devices (hard disk, floppy disk, CDs) o Input/Output devices (monitor, printer, keyboard, mouse) o Communication devices (Modem, NIC (Network Interface Card)). Bus Storage Communication Input Output Memory CPU Devices Devices Devices Devices e.g., Disk, CD, e.g., Modem, e.g., Keyboard, e.g., Monitor, and Tape and NIC Mouse Printer FIGURE 1.1 A computer consists of a CPU, memory, Hard disk, floppy disk, monitor, printer, and communication devices. CMPS161 Class Notes (Chap 01) Page 1 / 15 Kuo-pao Yang 1.2.1 Central Processing Unit (CPU) • The central processing unit (CPU) is the brain of a computer. • It retrieves instructions from memory and executes them. -

FUNDAMENTALS of COMPUTING (2019-20) COURSE CODE: 5023 502800CH (Grade 7 for ½ High School Credit) 502900CH (Grade 8 for ½ High School Credit)

EXPLORING COMPUTER SCIENCE NEW NAME: FUNDAMENTALS OF COMPUTING (2019-20) COURSE CODE: 5023 502800CH (grade 7 for ½ high school credit) 502900CH (grade 8 for ½ high school credit) COURSE DESCRIPTION: Fundamentals of Computing is designed to introduce students to the field of computer science through an exploration of engaging and accessible topics. Through creativity and innovation, students will use critical thinking and problem solving skills to implement projects that are relevant to students’ lives. They will create a variety of computing artifacts while collaborating in teams. Students will gain a fundamental understanding of the history and operation of computers, programming, and web design. Students will also be introduced to computing careers and will examine societal and ethical issues of computing. OBJECTIVE: Given the necessary equipment, software, supplies, and facilities, the student will be able to successfully complete the following core standards for courses that grant one unit of credit. RECOMMENDED GRADE LEVELS: 9-12 (Preference 9-10) COURSE CREDIT: 1 unit (120 hours) COMPUTER REQUIREMENTS: One computer per student with Internet access RESOURCES: See attached Resource List A. SAFETY Effective professionals know the academic subject matter, including safety as required for proficiency within their area. They will use this knowledge as needed in their role. The following accountability criteria are considered essential for students in any program of study. 1. Review school safety policies and procedures. 2. Review classroom safety rules and procedures. 3. Review safety procedures for using equipment in the classroom. 4. Identify major causes of work-related accidents in office environments. 5. Demonstrate safety skills in an office/work environment. -

An Early Program Proof by Alan Turing F

An Early Program Proof by Alan Turing F. L. MORRIS AND C. B. JONES The paper reproduces, with typographical corrections and comments, a 7 949 paper by Alan Turing that foreshadows much subsequent work in program proving. Categories and Subject Descriptors: 0.2.4 [Software Engineeringj- correctness proofs; F.3.1 [Logics and Meanings of Programs]-assertions; K.2 [History of Computing]-software General Terms: Verification Additional Key Words and Phrases: A. M. Turing Introduction The standard references for work on program proofs b) have been omitted in the commentary, and ten attribute the early statement of direction to John other identifiers are written incorrectly. It would ap- McCarthy (e.g., McCarthy 1963); the first workable pear to be worth correcting these errors and com- methods to Peter Naur (1966) and Robert Floyd menting on the proof from the viewpoint of subse- (1967); and the provision of more formal systems to quent work on program proofs. C. A. R. Hoare (1969) and Edsger Dijkstra (1976). The Turing delivered this paper in June 1949, at the early papers of some of the computing pioneers, how- inaugural conference of the EDSAC, the computer at ever, show an awareness of the need for proofs of Cambridge University built under the direction of program correctness and even present workable meth- Maurice V. Wilkes. Turing had been writing programs ods (e.g., Goldstine and von Neumann 1947; Turing for an electronic computer since the end of 1945-at 1949). first for the proposed ACE, the computer project at the The 1949 paper by Alan M. -

On-The-Fly Garbage Collection: an Exercise in Cooperation

8. HoIn, B.K.P. Determining lightness from an image. Comptr. Graphics and Image Processing 3, 4(Dec. 1974), 277-299. 9. Huffman, D.A. Impossible objects as nonsense sentences. In Machine Intelligence 6, B. Meltzer and D. Michie, Eds., Edinburgh U. Press, Edinburgh, 1971, pp. 295-323. 10. Mackworth, A.K. Consistency in networks of relations. Artif. Intell. 8, 1(1977), 99-118. I1. Marr, D. Simple memory: A theory for archicortex. Philos. Trans. Operating R.S. Gaines Roy. Soc. B. 252 (1971), 23-81. Systems Editor 12. Marr, D., and Poggio, T. Cooperative computation of stereo disparity. A.I. Memo 364, A.I. Lab., M.I.T., Cambridge, Mass., 1976. On-the-Fly Garbage 13. Minsky, M., and Papert, S. Perceptrons. M.I.T. Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1968. Collection: An Exercise in 14. Montanari, U. Networks of constraints: Fundamental properties and applications to picture processing. Inform. Sci. 7, 2(April 1974), Cooperation 95-132. 15. Rosenfeld, A., Hummel, R., and Zucker, S.W. Scene labelling by relaxation operations. IEEE Trans. Systems, Man, and Cybernetics Edsger W. Dijkstra SMC-6, 6(June 1976), 420-433. Burroughs Corporation 16. Sussman, G.J., and McDermott, D.V. From PLANNER to CONNIVER--a genetic approach. Proc. AFIPS 1972 FJCC, Vol. 41, AFIPS Press, Montvale, N.J., pp. 1171-1179. Leslie Lamport 17. Sussman, G.J., and Stallman, R.M. Forward reasoning and SRI International dependency-directed backtracking in a system for computer-aided circuit analysis. A.I. Memo 380, A.I. Lab., M.I.T., Cambridge, Mass., 1976. A.J. Martin, C.S. -

Anna Lysyanskaya Curriculum Vitae

Anna Lysyanskaya Curriculum Vitae Computer Science Department, Box 1910 Brown University Providence, RI 02912 (401) 863-7605 email: [email protected] http://www.cs.brown.edu/~anna Research Interests Cryptography, privacy, computer security, theory of computation. Education Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA Ph.D. in Computer Science, September 2002 Advisor: Ronald L. Rivest, Viterbi Professor of EECS Thesis title: \Signature Schemes and Applications to Cryptographic Protocol Design" Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA S.M. in Computer Science, June 1999 Smith College Northampton, MA A.B. magna cum laude, Highest Honors, Phi Beta Kappa, May 1997 Appointments Brown University, Providence, RI Fall 2013 - Present Professor of Computer Science Brown University, Providence, RI Fall 2008 - Spring 2013 Associate Professor of Computer Science Brown University, Providence, RI Fall 2002 - Spring 2008 Assistant Professor of Computer Science UCLA, Los Angeles, CA Fall 2006 Visiting Scientist at the Institute for Pure and Applied Mathematics (IPAM) Weizmann Institute, Rehovot, Israel Spring 2006 Visiting Scientist Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 1997 { 2002 Graduate student IBM T. J. Watson Research Laboratory, Hawthorne, NY Summer 2001 Summer Researcher IBM Z¨urich Research Laboratory, R¨uschlikon, Switzerland Summers 1999, 2000 Summer Researcher 1 Teaching Brown University, Providence, RI Spring 2008, 2011, 2015, 2017, 2019; Fall 2012 Instructor for \CS 259: Advanced Topics in Cryptography," a seminar course for graduate students. Brown University, Providence, RI Spring 2012 Instructor for \CS 256: Advanced Complexity Theory," a graduate-level complexity theory course. Brown University, Providence, RI Fall 2003,2004,2005,2010,2011 Spring 2007, 2009,2013,2014,2016,2018 Instructor for \CS151: Introduction to Cryptography and Computer Security." Brown University, Providence, RI Fall 2016, 2018 Instructor for \CS 101: Theory of Computation," a core course for CS concentrators. -

What Every Computer Scientist Should Know About Floating-Point Arithmetic

What Every Computer Scientist Should Know About Floating-Point Arithmetic DAVID GOLDBERG Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, 3333 Coyote Hill Road, Palo Alto, CalLfornLa 94304 Floating-point arithmetic is considered an esotoric subject by many people. This is rather surprising, because floating-point is ubiquitous in computer systems: Almost every language has a floating-point datatype; computers from PCs to supercomputers have floating-point accelerators; most compilers will be called upon to compile floating-point algorithms from time to time; and virtually every operating system must respond to floating-point exceptions such as overflow This paper presents a tutorial on the aspects of floating-point that have a direct impact on designers of computer systems. It begins with background on floating-point representation and rounding error, continues with a discussion of the IEEE floating-point standard, and concludes with examples of how computer system builders can better support floating point, Categories and Subject Descriptors: (Primary) C.0 [Computer Systems Organization]: General– instruction set design; D.3.4 [Programming Languages]: Processors —compders, optirruzatzon; G. 1.0 [Numerical Analysis]: General—computer arithmetic, error analysis, numerzcal algorithms (Secondary) D. 2.1 [Software Engineering]: Requirements/Specifications– languages; D, 3.1 [Programming Languages]: Formal Definitions and Theory —semantZcs D ,4.1 [Operating Systems]: Process Management—synchronization General Terms: Algorithms, Design, Languages Additional Key Words and Phrases: denormalized number, exception, floating-point, floating-point standard, gradual underflow, guard digit, NaN, overflow, relative error, rounding error, rounding mode, ulp, underflow INTRODUCTION tions of addition, subtraction, multipli- cation, and division. It also contains Builders of computer systems often need background information on the two information about floating-point arith- methods of measuring rounding error, metic. -

Florida Course Code Directory Computer Science Course Information 2019-2020

FLORIDA COURSE CODE DIRECTORY COMPUTER SCIENCE COURSE INFORMATION 2019-2020 Section 1007.2616, Florida Statutes, was amended by the Florida Legislature to include the definition of computer science and a requirement that computer science courses be identified in the Course Code Directory published on the Department of Education’s website. DEFINITION: The study of computers and algorithmic processes, including their principles, hardware and software designs, applications, and their impact on society, and includes computer coding and computer programming. SECONDARY COMPUTER SCIENCE COURSES Middle and high schools in each district, including combination schools in which any of grades 6-12 are taught, must provide an opportunity for students to enroll in a computer science course. If a school district does not offer an identified computer science course the district must provide students access to the course through the Florida Virtual School (FLVS) or through other means. COURSE NUMBER COURSE TITLE 0200000 M/J Computer Science Discoveries 0200010 M/J Computer Science Discoveries 1 0200020 M/J Computer Science Discoveries 2 0200305 Computer Science Discoveries 0200315 Computer Science Principles 0200320 AP Computer Science A 0200325 AP Computer Science A Innovation 0200335 AP Computer Science Principles 0200435 PRE-AICE Computer Studies IGCSE Level 0200480 AICE Computer Science 1 AS Level 0200485 AICE Computer Science 2 A Level 0200490 AICE Information Technology 1 AS Level 0200495 AICE Information Technology 2 A Level 0200800 IB Computer -

Introduction to High Performance Computing

Introduction to High Performance Computing Shaohao Chen Research Computing Services (RCS) Boston University Outline • What is HPC? Why computer cluster? • Basic structure of a computer cluster • Computer performance and the top 500 list • HPC for scientific research and parallel computing • National-wide HPC resources: XSEDE • BU SCC and RCS tutorials What is HPC? • High Performance Computing (HPC) refers to the practice of aggregating computing power in order to solve large problems in science, engineering, or business. • Purpose of HPC: accelerates computer programs, and thus accelerates work process. • Computer cluster: A set of connected computers that work together. They can be viewed as a single system. • Similar terminologies: supercomputing, parallel computing. • Parallel computing: many computations are carried out simultaneously, typically computed on a computer cluster. • Related terminologies: grid computing, cloud computing. Computing power of a single CPU chip • Moore‘s law is the observation that the computing power of CPU doubles approximately every two years. • Nowadays the multi-core technique is the key to keep up with Moore's law. Why computer cluster? • Drawbacks of increasing CPU clock frequency: --- Electric power consumption is proportional to the cubic of CPU clock frequency (ν3). --- Generates more heat. • A drawback of increasing the number of cores within one CPU chip: --- Difficult for heat dissipation. • Computer cluster: connect many computers with high- speed networks. • Currently computer cluster is the best solution to scale up computer power. • Consequently software/programs need to be designed in the manner of parallel computing. Basic structure of a computer cluster • Cluster – a collection of many computers/nodes. • Rack – a closet to hold a bunch of nodes.