Testimony of Ari Schwartz, Associate Director Center for Democracy And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adware-Searchsuite

McAfee Labs Threat Advisory Adware-SearchSuite June 22, 2018 McAfee Labs periodically publishes Threat Advisories to provide customers with a detailed analysis of prevalent malware. This Threat Advisory contains behavioral information, characteristics and symptoms that may be used to mitigate or discover this threat, and suggestions for mitigation in addition to the coverage provided by the DATs. To receive a notification when a Threat Advisory is published by McAfee Labs, select to receive “Malware and Threat Reports” at the following URL: https://www.mcafee.com/enterprise/en-us/sns/preferences/sns-form.html Summary Detailed information about the threat, its propagation, characteristics and mitigation are in the following sections: Infection and Propagation Vectors Mitigation Characteristics and Symptoms Restart Mechanism McAfee Foundstone Services The Threat Intelligence Library contains the date that the above signatures were most recently updated. Please review the above mentioned Threat Library for the most up to date coverage information. Infection and Propagation Vectors Adware-SearchSuite is a "potentially unwanted program" (PUP). PUPs are any piece of software that a reasonably security- or privacy-minded computer user may want to be informed of and, in some cases, remove. PUPs are often made by a legitimate corporate entity for some beneficial purpose, but they alter the security state of the computer on which they are installed, or the privacy posture of the user of the system, such that most users will want to be aware of them. Mitigation Mitigating the threat at multiple levels like file, registry and URL could be achieved at various layers of McAfee products. Browse the product guidelines available here (click Knowledge Center, and select Product Documentation from the Support Content list) to mitigate the threats based on the behavior described in the Characteristics and symptoms section. -

A Crawler-Based Study of Spyware on the Web

A Crawler-based Study of Spyware on the Web Alexander Moshchuk, Tanya Bragin, Steven D. Gribble, and Henry M. Levy Department of Computer Science & Engineering University of Washington {anm, tbragin, gribble, levy}@cs.washington.edu Abstract servers [16]. The AOL scan mentioned above has provided simple summary statistics by directly examining desktop in- Malicious spyware poses a significant threat to desktop fections [2], while a recent set of papers have considered security and integrity. This paper examines that threat from user knowledge of spyware and its behavior [6, 29]. an Internet perspective. Using a crawler, we performed a In this paper we change perspective, examining the na- large-scale, longitudinal study of the Web, sampling both ture of the spyware threat not on the desktop but from an executables and conventional Web pages for malicious ob- Internet point of view. To do this, we conduct a large-scale jects. Our results show the extent of spyware content. For outward-looking study by crawling the Web, downloading example, in a May 2005 crawl of 18 million URLs, we found content from a large number of sites, and then analyzing it spyware in 13.4% of the 21,200 executables we identified. to determine whether it is malicious. In this way, we can At the same time, we found scripted “drive-by download” answer several important questions. For example: attacks in 5.9% of the Web pages we processed. Our analy- sis quantifies the density of spyware, the types of of threats, • How much spyware is on the Internet? and the most dangerous Web zones in which spyware is • Where is that spyware located (e.g., game sites, chil- likely to be encountered. -

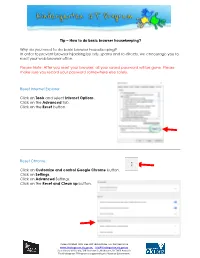

Tip – How to Do Basic Browser Housekeeping?

Tip – How to do basic browser housekeeping? Why do you need to do basic browser housekeeping? In order to prevent browser hijacking by ads, spams and re-directs, we encourage you to reset your web browser often. Please Note: After you reset your browser, all your saved password will be gone. Please make sure you record your password somewhere else safely. _______________________________________________________________________________________ Reset Internet Explorer Click on Tools and select Internet Options . Click on the Advanced tab. Click on the Reset button. _______________________________________________________________________________________ Reset Chrome Click on Customize and control Google Chrome button. Click on Settings . Click on Advanced Settings. Click on the Reset and Clean up button. Phone: (03) 8664 7001 Free Call: 1800 629 835 Fax: (03) 9639 2175 www.kindergarten.vic.gov.au [email protected] State Library of Victoria, 328 Swanston St, Melbourne, VIC 3000 Australia The Kindergarten IT Program is supported by the Victorian Government. Reset Firefox In the address bar of the FireFox type in about:support and hit Enter. Click Refresh Firefox… button. A window will appear showing the details of this action. Click Refresh Firefox button. _______________________________________________________________________________________ Clear website data in Safari Click on Safari tab and select Preferences… Click Privacy tab. Click Manage Website Data… Click on Remove All . Phone: (03) 8664 7001 Free Call: 1800 629 835 Fax: (03) 9639 2175 www.kindergarten.vic.gov.au [email protected] State Library of Victoria, 328 Swanston St, Melbourne, VIC 3000 Australia The Kindergarten IT Program is supported by the Victorian Government. Reset Edge Click on Settings and More button. -

COVID-19 Updates and Resources for Local Governments G Tuesday, March 23, 2021 Welcome Greeting

COVID-19 Updates and Resources for Local Governments g Tuesday, March 23, 2021 Welcome Greeting Kayla Rosen Departmental Analyst, Community Engagement and Finance, Department of Treasury 2 Tools and Resources for Local Governments: 11th Webinar Tuesday, March 23, 2021 – 2 p.m. – 3 p.m. I. Welcome & Introductions Heather Frick, Bureau Director, Bureau of Local Government and School Services, Michigan Department of Treasury I. Treasury Update a. CARES Act Grant b. FDCVT Grant c. Overviews of Recreational Marijuana Payments d. American Rescue Plan Eric Bussis, Chief Economist and Director of the Office of Revenue and Tax Analysis, Michigan Department of Treasury I. Cybersecurity for Local Governments Derek Larson, Acting Deputy Chief Security Officer, Department of Technology, Management and Budget (DTMB) I. Question and Answer II. Closing Remarks Heather Frick, Bureau Director, Bureau of Local Government and School Services, Michigan Department of Treasury 3 Welcome & Introductions Heather Frick Bureau Director, Bureau of Local Government and School Services, Department of Treasury 4 Treasury Local Government Funding Update Eric Bussis Chief Economist and Director Office of Revenue and Tax Analysis Michigan Department of Treasury 5 Treasury Update • CARES Act Grant • FDCVT Grant Agenda • Overviews of Recreational Marijuana Payments • American Rescue Plan 6 First Responder Hazard Pay Premiums Program (FRHPPP) • Payments made to 740 applicants, supporting approximately 37,500 first responders • 97 applications were selected for further federal -

The Emergence of Exploit-As-A-Service

Manufacturing Compromise: The Emergence of Exploit-as-a-Service Chris Grier† Lucas Ballard2 Juan Caballerox Neha Chachra∗ Christian J. Dietrichq Kirill Levchenko∗ Panayiotis Mavrommatis2 Damon McCoyz Antonio Nappax Andreas Pitsillidis∗ Niels Provos2 M. Zubair Rafiquex Moheeb Abu Rajab2 Christian Rossowq Kurt Thomasy Vern Paxson† Stefan Savage∗ Geoffrey M. Voelker∗ y University of California, Berkeley ∗ University of California, San Diego 2 Google International Computer Science Institute x IMDEA Software Institute q University of Applied Sciences Gelsenkirchen z George Mason University ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION We investigate the emergence of the exploit-as-a-service model for In this work we investigate the emergence of a new paradigm: the driveby browser compromise. In this regime, attackers pay for an exploit-as-a-service economy that surrounds browser compromise. exploit kit or service to do the “dirty work” of exploiting a vic- This model follows in the footsteps of a dramatic evolution in the tim’s browser, decoupling the complexities of browser and plugin world of for-profit malware over the last five years, where host com- vulnerabilities from the challenges of generating traffic to a web- promise is now decoupled from host monetization. Specifically, the site under the attacker’s control. Upon a successful exploit, these means by which a host initially falls under an attacker’s control are kits load and execute a binary provided by the attacker, effectively now independent of the means by which an(other) attacker abuses transferring control of a victim’s machine to the attacker. the host in order to realize a profit. This shift in behavior is exem- In order to understand the impact of the exploit-as-a-service plified by the pay-per-install model of malware distribution, where paradigm on the malware ecosystem, we perform a detailed anal- miscreants pay for compromised hosts via the underground econ- ysis of the prevalence of exploit kits, the families of malware in- omy [4, 41]. -

Spyware & Adware Products

AdwareAdware/Spyware/Spyware ProductsProducts && RecommendationsRecommendations UCLAUCLA OfficeOffice ofof InstructionalInstructional DevelopmentDevelopment MikeMike TakahashiTakahashi AgendaAgenda WhatWhat isis AdwareAdware/Spyware/Spyware KnownKnown AdwareAdware/Spyware/Spyware ProductsProducts AntiAnti AdwareAdware/Spyware/Spyware RemovalRemoval ProductProduct ComparisonsComparisons TipsTips && RecommendationsRecommendations AdwareAdware AdwareAdware cancan bebe softwaresoftware thatthat generatesgenerates advertisementsadvertisements suchsuch asas poppop--upup windowswindows oror hotlinkshotlinks onon webweb pages.pages. ItIt maymay addadd linkslinks toto youryour favoritesfavorites andand youryour desktop.desktop. ItIt cancan changechange youryour homehome pagepage andand youryour searchsearch engineengine toto sitessites thatthat earnearn incomeincome fromfrom variousvarious advertisers.advertisers. Source http://www.microsoft.com/windows/ie/community/columns/adware.mspx AdwareAdware ExamplesExamples What?!What?! MyMy computercomputer isis infected!infected! OrOr isis it?it? AdwareAdware ExamplesExamples WellWell--knownknown AdwareAdware ProgramsPrograms toto AvoidAvoid HotbarHotbar (Add(Add--ons)ons) Adds graphical skins to Browser and Email clients Adds toolbars and search button BlockCheckerBlockChecker ClipGenieClipGenie CometComet CursorCursor GatorGator WinFixerWinFixer StumbleUponStumbleUpon WeatherBugWeatherBug SpywareSpyware SpywareSpyware isis computercomputer softwaresoftware thatthat collectscollects -

Remove ANY TOOLBAR from Internet Explorer, Firefox and Chrome

Remove ANY TOOLBAR from Internet Explorer, Firefox and Chrome Browser toolbars have been around for years, however, in the last couple of months they became a huge mess. Unfortunately, lots of free software comes with more or less unwanted add-ons or browser toolbars. These are quite annoying because they may: Change your homepage and your search engine without your permission or awareness Track your browsing activities and searches Display annoying ads and manipulate search results Take up a lot of (vertical) space inside the browser Slow down your browser and degrade your browsing experience Fight against each other and make normal add-on handling difficult or impossible Become difficult or even impossible for the average user to fully uninstall Toolbars are not technically not a virus, but they do exhibit plenty of malicious traits, such as rootkit capabilities to hook deep into the operating system, browser hijacking, and in general just interfering with the user experience. The industry generally refers to it as a “PUP,” or potentially unwanted program. Generally speaking, toolbars are ad-supported (users may see additional banner, search, pop-up, pop-under, interstitial and in-text link advertisements) cross web browser plugin for Internet Explorer, Firefox and Chrome, and distributed through various monetization platforms during installation. Very often users have no idea where did it come from, so it’s not surprising at all that most of them assume that the installed toolbar is a virus. For example, when you install iLivid Media Player, you will also agree to change your browser homepage to search.conduit.com, set your default search engine to Conduit Search, and install the AVG Search-Results Toolbar. -

Pikes Peak Library District Takes Malware out of Circulation Malwarebytes Provides Defense Without Compromising Openness

CASE STUDY Pikes Peak Library District takes malware out of circulation Malwarebytes provides defense without compromising openness Business profile INDUSTRY Pikes Peak Library District (PPLD) is a nationally recognized Government system of public libraries serving residents in El Paso County, Colorado. With fourteen facilities, online resources, and mobile BUSINESS CHALLENGE library service, PPLD responds to the unique needs of individual Prevent malware, including ransomware, neighborhoods and the community at large. A large number of from infecting computers while computers used by staf and patrons have internet connectivity. centralizing control To protect them from ransomware and other advanced malware, IT ENVIRONMENT PPLD chose Malwarebytes. Webroot antivirus, Deep Freeze Instant Restore Malwarebytes surpasses our antivirus’ SOLUTION prevention and detection features and runs Malwarebytes Endpoint Security with almost zero performance impact on users’ machines. RESULTS —Richard Peters, Chief Information Officer, • Stopped malware, including Pikes Peak Library District ransomware, from infecting computers • Significantly reduced labor costs Business challenge through better detection and Centralizing control over endpoints centralized management Four hundred and seventy-five PPLD employees operate library • Eliminated downtime and disruption facilities, manage book and media acquisition, and help patrons associated with malware find information. PPLD has 14 locations, plus a mobile Bookmobile and a Library Express kiosk. In addition to staf computers, PPLD provides computers for library patrons’ use. As an organization that exists to facilitate access to print, audio, visual, and electronic information, it’s not surprising that internet-based cyber threats target the browsers, Java, and Adobe Flash applications. Staf members encountered browser hijacking, popup ads, malicious email attachments, and drive-by downloads. -

Download Getting Rid of Norton Toolbar Firefox Rar for Ipod

Contact Imprint Aeropostale printable job application Getting rid of norton Persuasive newspaper articles toolbar firefox online netspend reload pack The Steps To Fix Firefox Browser With Norton Antivirus?. If the file is regenerated when you restart the computer, remove it again and in its tums recall 2013 place, create an empty text file (e.g., with Notepad), rename it "coFFPlgn.dll" and change the properties to "read-only". Die Version 2009 boneless ist am 9. September 2008 in Amerika erschienen. Wie bei allen Norton- chicken breast Produkten verzögerte sich die Deutschland-Veröffentlichung um einige recipes Wochen. Norton offers three scan types. In the screen where you can oven baked choose which scan to run, other options are available that may be useful. For example, "Norton insight" looks through your files and decides how likely they are to contain malware. This can show you what programs Norton deems as high risk. have a "Settings" button with an uninstall menu option. To see which version of the toolbar is installed, visit. If you later want to remove the toolbar, the easiest method is to uninstall ZoneAlarm and then do a custom installation and deselect the toolbar option. [10]. If you have any questions, come by the Help Desk at Hardman & Jacobs Undergraduate Learning Center Room 105, call 646- 1840, or email us at. "Safe web" gives you full browser protection by keeping an eye on what you are doing online and stopping any threats. For antivirus protection within a browser, this is very effective. Norton doesn't let suspicious downloads complete, and phishing pages cause a warning page to appear. -

THE UNINVITED GUEST a Browser Hijacking Experience, Dissected

THE UNINVITED GUEST A Browser Hijacking Experience, Dissected Sponsored by ANCHOR INTELLIGENCE: THE UNINVITED GUEST: A BROWSER HIJACKING EXPERIENCE, DISSECTED INTRODUCTION The continued growth of the Internet and online advertising has created an appealing medium through which fraudsters distribute malware and perpetrate a wide range of malicious activities. Over the past six months, Anchor Intelligence has identified a surge in browser hijacking attacks perpetrated through online advertising campaigns. These compromised ads, found on various ad networks and search engines, have been traced to schemes designed to defraud unsuspecting users by capturing their credit card information and account passwords, forcing ad clicks without users’ consent, and manipulating personal data such as cookies. By targeting the browser, a user’s primary gateway to the Internet, browser-hijacking malware has emerged as one of the most powerful and dangerous online exploits. The hijacker is an uninvited guest, which sits dormant in the background of the user’s experience, looking over her shoulder to log each keystroke as she enters her bank password, redirect her to malicious websites when she expects to see search results pages, or simply leverage her browser to make http requests unbeknownst to her. In response to the explosion of browser hijacking exploits identified across its network, Anchor Intelligence is issuing “The Uninvited Guest: A Browser Hijacking Experience, Dissected” to educate end users, ad buyers, and ad sellers about how to recognize and avoid common tactics used by fraudsters to compromise their systems. Section I of the report provides background on browser hijacking and describes infection vectors, payloads, and attacks. -

Internet Security (An Article from the Internet)

First National Bank Internet Security (An Article from the Internet) If terms such as 'phishing', 'zombies' and 'DoS' have you thrashing around in the dark, this article will help you get acquainted – and get the upper hand – with these and other online perils. Table of Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 3 2. What Your Up Against ............................................................................................................................... 3 Viruses and worms .................................................................................................................................... 3 Adware, spyware and key loggers ............................................................................................................ 4 Phishing ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Spam ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Browser hijacking ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Family, friends and colleagues .................................................................................................................. 6 Zombies and DoS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Tech Tip of the Month

Let’s Make a Snow Twin Brandon Fourth Grade Teacher Sandy Kuik Tech Tip of the Month Celebrating the last day of winter had more meaning this year as the fourth graders at Submitted by the RBSD Technology Committee Brandon School got busy building snowmen indoors! Their usual materials of snow, sticks, rocks, and scarves were swapped out for marshmallows, pretzels, M&M’s, and fruit roll-ups as they worked with a classmate to make a snow twin. That sounds like Hackers, Data Privacy, and Protection a breeze, doesn’t it? Well, it wasn’t quite that easy. What made this learning activity unique, and quite difficult, was that partners were behind desk dividers and had to rely Being aware of the possible dangers online is the first step to protecting your only on verbal directions during the build to create a snowman that was as close to their information and keeping your computer safe. Updating your computer and partners as possible. No peeking was allowed! This blind build served as a culminating browser, being aware of phishing scams, using unique passwords, being leery of activity for the communication unit of the new Social Emotional Learning curriculum. attachments, usb drives, and downloads, and finally, installing antivirus software It gave the fourth graders the opportunity to practice effective strategies used when that has been deemed “top ranking” are all ways to protect you and your family communicating with others, known as boosters, and to avoid bloopers, the roadblocks while online. that interfere with the ability to work effectively in a cooperative learning activity.