Jackie Robinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numbered Panel 1

PRIDE 1A 1B 1C 1D 1E The African-American Baseball Experience Cuban Giants season ticket, 1887 A f r i c a n -American History Baseball History Courtesy of Larry Hogan Collection National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 1 8 4 5 KNICKERBOCKER RULES The Knickerbocker Base Ball Club establishes modern baseball’s rules. Black Teams Become Professional & 1 8 5 0 s PLANTATION BASEBALL The first African-American professional teams formed in As revealed by former slaves in testimony given to the Works Progress FINDING A WAY IN HARD TIMES 1860 – 1887 the 1880s. Among the earliest was the Cuban Giants, who Administration 80 years later, many slaves play baseball on plantations in the pre-Civil War South. played baseball by day for the wealthy white patrons of the Argyle Hotel on Long Island, New York. By night, they 1 8 5 7 1 8 5 7 Following the Civil War (1861-1865), were waiters in the hotel’s restaurant. Such teams became Integrated Ball in the 1800s DRED SCOTT V. SANDFORD DECISION NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BA S E BA L L PL AY E R S FO U N D E D lmost as soon as the game’s rules were codified, Americans attractions for a number of resort hotels, especially in The Supreme Court allows slave owners to reclaim slaves who An association of amateur clubs, primarily from the New York City area, organizes. R e c o n s t ruction was meant to establish Florida and Arkansas. This team, formed in 1885 by escaped to free states, stating slaves were property and not citizens. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

2017 Information & Record Book

2017 INFORMATION & RECORD BOOK OWNERSHIP OF THE CLEVELAND INDIANS Paul J. Dolan John Sherman Owner/Chairman/Chief Executive Of¿ cer Vice Chairman The Dolan family's ownership of the Cleveland Indians enters its 18th season in 2017, while John Sherman was announced as Vice Chairman and minority ownership partner of the Paul Dolan begins his ¿ fth campaign as the primary control person of the franchise after Cleveland Indians on August 19, 2016. being formally approved by Major League Baseball on Jan. 10, 2013. Paul continues to A long-time entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sherman has been responsible for establishing serve as Chairman and Chief Executive Of¿ cer of the Indians, roles that he accepted prior two successful businesses in Kansas City, Missouri and has provided extensive charitable to the 2011 season. He began as Vice President, General Counsel of the Indians upon support throughout surrounding communities. joining the organization in 2000 and later served as the club's President from 2004-10. His ¿ rst startup, LPG Services Group, grew rapidly and merged with Dynegy (NYSE:DYN) Paul was born and raised in nearby Chardon, Ohio where he attended high school at in 1996. Sherman later founded Inergy L.P., which went public in 2001. He led Inergy Gilmour Academy in Gates Mills. He graduated with a B.A. degree from St. Lawrence through a period of tremendous growth, merging it with Crestwood Holdings in 2013, University in 1980 and received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s and continues to serve on the board of [now] Crestwood Equity Partners (NYSE:CEQP). -

“The Royals of Sir Cedric” by Steve Treder of the Hardball Times December 21, 2004

“The Royals of Sir Cedric” by Steve Treder of The Hardball Times December 21, 2004 At its inception, the most successful expansion franchise in pre-free agency baseball history didn’t impress many observers. The Kansas City Royals devoted most of their expansion draft picks to unproven young players, in distinct contrast to the approach taken by their companion A.L. expansion team, the Seattle Pilots. Take a look at the first ten choices of each club, noting each player’s age and major league experience as of the October 15, 1968 draft: Royals: Player Age ML Seasons ML Experience 1. Roger Nelson 24 2 78 innings 2. Joe Foy 25 3 1,515 at-bats 3. Jim Rooker 26 1 5 innings 4. Joe Keough 22 1 98 at-bats 5. Steve Jones 27 2 36 innings 6. Jon Warden 22 1 37 innings 7. Ellie Rodriguez 22 1 24 at-bats 8. Dave Morehead 25 6 665 innings 9. Mike Fiore 24 1 19 at-bats 10. Bob Oliver 25 1 2 at-batsAverage Age - 24.2 Average ML Seasons - 1.9 Average ML Experience - 332 at-bats, 164 innings Pilots: Player Age ML Seasons ML Experience 1. Don Mincher 30 9 2,476 at-bats 2. Tommy Harper 28 7 2,547 at-bats 3. Ray Oyler 30 4 986 at-bats 4. Gerry McNertney 32 4 537 at-bats 5. Buzz Stephen 24 1 11 innings 6. Chico Salmon 27 5 1,304 at-bats 7. Diego Segui 31 7 889 innings 8. Tommy Davis 29 10 4,032 at-bats 9. -

![1939-07-14 [P B-6]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5819/1939-07-14-p-b-6-485819.webp)

1939-07-14 [P B-6]

■■■ Reds Bob Up With Bigger Lead Than Yankees as Start Second Half ■ Majors y Sports Mirror Lose or Draw Champions Drop Hartnett Draws Bv MM Auoclatod Preu. Win, Today a year ago—Lefty Grove, star Red Sox pitcher, forced out By FRANCIS E. STAN. 6th in Row as of game in sixth inning with First Blood in sudden arm ailment as he won An Authority Speaks on Joe Gordon 14th game of season. Three United If it did nothing else, baseball's latest all-star show exposed the ln- years ago—Full States team of 384 athletes as- flelding greatness of Joe Gordon for all to see. The young Yankee second Bosox Win sured for Berlin Olympics as baseman emerged sharing the heroics with Bob Feller, who is getting some Cub-Phil Feud women’s track team raised funds recognition of his own, and around the country now the critics are saying to send IS. that Gordon is the No. 1 man at his position. National Pacemakers Five years ago—Cavalcade won Bill Reinhart was talking about the youngster a few days before the Trounces Club Irked $30,000 Arlington Classic, beat- all-star game. Reinhart is George Washington's football and basket ball Blank Giants, Go ing Discovery by four lengths; Because Lou Gehrig, ill with coach and one of the two men who know Gordon best. The other is Arny Idled lumbago, kept record of in- Manager Joe McCarthy of the Yankees. 6V2 Games Up string games At 'Dream' Game tact by batting in first inning for • “He's the finest .young ballplayer I ever saw at the start of his career,” JUDSON BAILEY, Yanks. -

Kit Young's Sale

KIT YOUNG’S SALE #91 1952 ROYAL STARS OF BASEBALL DESSERT PREMIUMS These very scarce 5” x 7” black & white cards were issued as a premium by Royal Desserts in 1952. Each card includes the inscription “To a Royal Fan” along with the player’s facsimile autograph. These are rarely offered and in pretty nice shape. Ewell Blackwell Lou Brissie Al Dark Dom DiMaggio Ferris Fain George Kell Reds Indians Giants Red Sox A’s Tigers EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX EX+ EX+/EX-MT EX+ $55.00 $55.00 $39.00 $120.00 $55.00 $99.00 Stan Musial Andy Pafko Pee Wee Reese Phil Rizzuto Eddie Robinson Ray Scarborough Cardinals Dodgers Dodgers Yankees White Sox Red Sox EX+ EX+ EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT $265.00 $55.00 $175.00 $160.00 $55.00 $55.00 1939-46 SALUTATION EXHIBITS Andy Seminick Dick Sisler Reds Reds EX-MT EX+/EX-MT $55.00 $55.00 We picked up a new grouping of this affordable set. Bob Johnson A’s .................................EX-MT 36.00 Joe Kuhel White Sox ...........................EX-MT 19.95 Luke Appling White Sox (copyright left) .........EX-MT Ernie Lombardi Reds ................................. EX 19.00 $18.00 Marty Marion Cardinals (Exhibit left) .......... EX 11.00 Luke Appling White Sox (copyright right) ........VG-EX Johnny Mize Cardinals (U.S.A. left) ......EX-MT 35.00 19.00 Buck Newsom Tigers ..........................EX-MT 15.00 Lou Boudreau Indians .........................EX-MT 24.00 Howie Pollet Cardinals (U.S.A. right) ............ VG 4.00 Joe DiMaggio Yankees ........................... -

The 112Th World Series Chicago Cubs Vs

THE 112TH WORLD SERIES CHICAGO CUBS VS. CLEVELAND INDIANS SUNDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2016 GAME 5 - 7:15 P.M. (CT) FIRST PITCH WRIGLEY FIELD, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 2016 WORLD SERIES RESULTS GAME (DATE RESULT WINNING PITCHER LOSING PITCHER SAVE ATTENDANCE Gm. 1 - Tues., Oct. 25th CLE 6, CHI 0 Kluber Lester — 38,091 Gm. 2 - Wed., Oct. 26th CHI 5, CLE 1 Arrieta Bauer — 38,172 Gm. 3 - Fri., Oct. 28th CLE 1, CHI 0 Miller Edwards Allen 41,703 Gm. 4 - Sat., Oct. 29th CLE 7, CHI 2 Kluber Lackey — 41,706 2016 WORLD SERIES SCHEDULE GAME DAY/DATE SITE FIRST PITCH TV/RADIO 5 Sunday, October 30th Wrigley Field 8:15 p.m. ET/7:15 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio Monday, October 31st OFF DAY 6* Tuesday, November 1st Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 7* Wednesday, November 2nd Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio *If Necessary 2016 WORLD SERIES PROBABLE PITCHERS (Regular Season/Postseason) Game 5 at Chicago: Jon Lester (19-5, 2.44/2-1, 1.69) vs. Trevor Bauer (12-8, 4.26/0-1, 5.00) Game 6 at Cleveland (if necessary): Josh Tomlin (13-9, 4.40/2-0/1.76) vs. Jake Arrieta (18-8, 3.10/1-1, 3.78) SERIES AT 3-1 CUBS AND INDIANS IN GAME 5 This marks the 47th time that the World Series stands at 3-1. Of • The Cubs are 6-7 all-time in Game 5 of a Postseason series, the previous 46 times, the team leading 3-1 has won the series 40 including 5-6 in a best-of-seven, while the Indians are 5-7 times (87.0%), and they have won Game 5 on 26 occasions (56.5%). -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

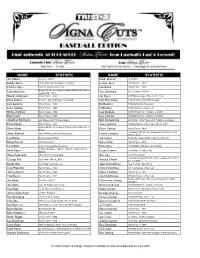

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

Mediaguide.Pdf

American Legion Baseball would like to thank the following: 2017 ALWS schedule THURSDAY – AUGUST 10 Game 1 – 9:30am – Northeast vs. Great Lakes Game 2 – 1:00pm – Central Plains vs. Western Game 3 – 4:30pm – Mid-South vs. Northwest Game 4 – 8:00pm – Southeast vs. Mid-Atlantic Off day – none FRIDAY – AUGUST 11 Game 5 – 4:00pm – Great Lakes vs. Central Plains Game 6 – 7:30pm – Western vs. Northeastern Off day – Mid-Atlantic, Southeast, Mid-South, Northwest SATURDAY – AUGUST 12 Game 7 – 11:30am – Mid-Atlantic vs. Mid-South Game 8 – 3:30pm – Northwest vs. Southeast The American Legion Game 9 – Northeast vs. Central Plains Off day – Great Lakes, Western Code of Sportsmanship SUNDAY – AUGUST 13 Game 10 – Noon – Great Lakes vs. Western I will keep the rules Game 11 – 3:30pm – Mid-Atlantic vs. Northwest Keep faith with my teammates Game 12 – 7:30pm – Southeast vs. Mid-South Keep my temper Off day – Northeast, Central Plains Keep myself fit Keep a stout heart in defeat MONDAY – AUGUST 14 Game 13 – 3:00pm – STARS winner vs. STRIPES runner-up Keep my pride under in victory Game 14 – 7:00pm – STRIPLES winner vs. STARS runner-up Keep a sound soul, a clean mind And a healthy body. TUESDAY – AUGUST 14 – CHAMPIONSHIP TUESDAY Game 15 – 7:00pm – winner game 13 vs. winner game 14 ALWS matches Stars and Stripes On the cover Top left: Logan Vidrine pitches Texarkana AR into the finals The 2017 American Legion World Series will salute the Stars of the ALWS championship with a three-hit performance and Stripes when playing its 91st World Series (92nd year) against previously unbeaten Rockport IN. -

Achieve Gr. 6-A League of Their

5/17/2021 Achieve3000: Lesson Printed by: Thomas Dietz Printed on: May 17, 2021 A League of Their Own Article RED BANK, New Jersey (Achieve3000, May 5, 2021). From 1920 into the 1950s, summer Sundays in parts of Kansas City revolved around Black baseball games. Families dressed in their best. Crowds by the thousands gravitated to the stadium. Fans watched their Kansas City Monarchs play the Chicago American Giants, the Homestead Grays, or the Newark Eagles. It was more than a joyful day out at the ballgame. It was a celebration. That scene captures the excitement of the "Negro Leagues," as they were known at the time. In that era, segregation policies blocked Black citizens from enjoying many aspects of American life. This included Major League Photo Credit: AP Photo/Matty Baseball. Black baseball teams were a source of fun and community pride. Zimmerman, File In this photo from 1942, Kansas City Chicago-based Andrew "Rube" Foster had the grand vision to launch the Monarchs pitcher Leroy Satchel Negro National League. It started in 1920 with eight teams. In 1933, the Paige warms up before a Negro League game. New Negro National League was founded, followed by the Negro American League. The financial fortunes of the Negro Leagues would ebb and flow over the next three decades. But their popularity and high-level of play stayed strong. Between World War I (1914–1918) and World War II (1939–1945), baseball's place as America's national pastime was indisputable. The segregated Major Leagues fielded Hall of Fame legends like Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Dazzy Vance. -

'72 Rewind: a New Murderers' Row?

'72 Rewind: A New Murderers' Row? (The Chicago Baseball Museum will pay tribute to Dick Allen and the 1972 White Sox in a June 25 fundraiser at U.S. Cellular Field. We will chronicle the events of that epic season here in the weeks ahead. Sport magazine published this story in its August, 1972 edition.) By George Vass Posted on Monday, May 28 In Chuck Tanner's mind there is no question that he has a new “Murderer's Row” in the making in his White Sox. “I'm already convinced that this is the most power- ful hitting team the Sox have had in their history,” said Manager Tanner, “although I don't know if you could call it a 'Murderers' Row' in the old sense. “But potentially it is a 'Murderers' Row' of a differ- ent kind. What I mean by that is that while we have great home run power we also have a balance of fine line-drive hitters, men like Pat Kelly. We have both power and .300 hitting in good balance in our line-up. Allen, Melton and May form one of “When the phrase Murderers' Row is used it brings baseball's potent power trios. to mind the kind of teams in the past that had great home run power, but not necessarily the line-drive hitting, the balance of speed and power that we have.” As the Sox amply demonstrated by their early foot this season, led by the bombardment of Bill Melton, Dick Allen, Carlos May, Ed Herrmann, and Ken Henderson, they have the kind of power attributed to legendary clubs of the past.