248 the Chii1·Ch of Ireland. of Them Might Have Sought and Obtained

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

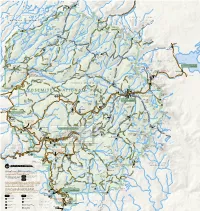

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK O C Y Lu H M Tioga Pass Entrance 9945Ft C Glen Aulin K T Ne Ee 3031M E R Hetc C Gaylor Lakes R H H Tioga Road Closed

123456789 il 395 ra T Dorothy Lake t s A Bond C re A Pass S KE LA c i f i c IN a TW P Tower Peak Barney STANISLAUS NATIONAL FOREST Mary Lake Lake Buckeye Pass Twin Lakes 9572ft EMIGRANT WILDERNESS 2917m k H e O e O r N V C O E Y R TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST N Peeler B A Lake Crown B C Lake Haystack k Peak e e S Tilden r AW W Schofield C TO Rock Island OTH IL Peak Lake RI Pass DG D Styx E ER s Matterhorn Pass l l Peak N a Slide E Otter F a Mountain S Lake ri e S h Burro c D n Pass Many Island Richardson Peak a L Lake 9877ft R (summer only) IE 3010m F LE Whorl Wilma Lake k B Mountain e B e r U N Virginia Pass C T O Virginia S Y N Peak O N Y A Summit s N e k C k Lake k c A e a C i C e L C r N r Kibbie d YO N C n N CA Lake e ACK AI RRICK K J M KE ia in g IN ir A r V T e l N k l U e e pi N O r C S O M Y Lundy Lake L Piute Mountain N L te I 10541ft iu A T P L C I 3213m T Smedberg k (summer only) Lake e k re e C re Benson Benson C ek re Lake Lake Pass C Vernon Creek Mount k r e o Gibson e abe Upper an r Volunteer McC le Laurel C McCabe E Peak rn Lake u Lake N t M e cCa R R be D R A Lak D NO k Rodgers O I es e PLEASANT EA H N EL e Lake I r l Frog VALLEY R i E k G K C E LA e R a e T I r r Table Lake V North Peak T T C N Pettit Peak A INYO NATIONAL FOREST O 10788ft s Y 3288m M t ll N Fa s Roosevelt ia A e Mount Conness TILT r r Lake Saddlebag ILL VALLEY e C 12590ft (summer only) h C Lake ill c 3837m Lake Eleanor ilt n Wapama Falls T a (summer only) N S R I Virginia c A R i T Lake f N E i MIGUEL U G c HETCHY Rancheria Falls O N Highway 120 D a MEADOW -

December 1942

Vol . XXI December, 1942 No. 12 Yosemite Nature Notes THE MONTHLY PUBLICATION OF THE YOSEMITE NATURALIST DEPARTMENT AND THE YOSEMITE NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION F. A . Kittredge, Superintendent C. F . Brockman, Park Naturalist M. E . Beatty, Assoc. Park Naturalist H . C . Parker, Ass 't Park Naturalist VOL . XXI DECEMBER, 1942 NO . 12 INTO THE BACK COUNTRY By Bob W. Prudhomme, Museum Assistant You have all heard of the world- Hemlock and of the White-bark Pine famous wonders of Yosemite Valley, which ascend high upon the moun- its cliffs and thundering waterfalls, tain slopes—trees which might well but I wonder how many of you are be called the "Sentinels of the High aware of the vast wilderness of Sierra ." And, too, the alpenglow peaks and passes, and the countless from May Lake is unforgettable, as lakes and lush mountain meadows the dying sun throws its rich colors that lie waiting along the trails be- of rose and coral over the landscape. yond the crowds on the valley floor . Such great mountains as Conness, On the week-end of August 22, Dana, Gibbs and Mammoth as 1942, a fellow employee and the viewed from a vantage point above writer were fortunate to spend two the lake, assume a new beauty quite days at May Lake, a beautiful gla- distinct from their appearance earl- cial tarn nestled at the foot of Mount ier in the day . Then, as nightfall Hoffmann, which stands in the an- casts its heavy shadows over the proximate center of the park . There range and the first evening star ap- are few areas in the Yosemite region rears, the warmth and friendship of which combine such a variety of the campfire beckon. -

Sierra Nevada Mountain Yellow-Legged Frog

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF INTERIOR CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL ) PETITION TO LIST THE SIERRA DIVERSITY AND PACIFIC RIVERS ) NEVADA MOUNTAIN YELLOW- COUNCIL ) LEGGED FROG (RANA MUSCOSA) AS ) AN ENDANGERED SPECIES UNDER ) THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT Petitioners ) ________________________________ ) February 8, 2000 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Center for Biological Diversity and Pacific Rivers Council formally request that the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“USFWS”) list the Sierra Nevada population of the mountain yellow-legged frog (Rana muscosa) as endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. § 1531 - 1544. These organizations also request that mountain yellow- legged frog critical habitat be designated concurrent with its listing. The petitioners are conservation organizations with an interest in protecting the mountain yellow-legged frog and all of earth’s remaining biodiversity. The mountain yellow-legged frog in the Sierra Nevada is geographically, morphologically and genetically distinct from mountain yellow legged frogs in southern California. It is undisputedly a “species” under the ESA’s listing criteria and warrants recognition as such. The mountain yellow-legged frog was historically the most abundant frog in the Sierra Nevada. It was ubiquitously distributed in high elevation water bodies from southern Plumas County to southern Tulare County. It has since declined precipitously. Recent surveys have found that the species has disappeared from between 70 and 90 percent of its historic localities. What populations remain are widely scattered and consist of few breeding adults. Declines were first noticed in the 1950's, escalated in the 1970's and 1980's, and continue today. What was recently thought to be one of the largest remaining populations, containing over 2000 adult frogs in 1996, completely crashed in the past three years; only 2 frogs were found in the same area in 1999. -

Wes Hildreth

Transcription: Grand Canyon Historical Society Interviewee: Wes Hildreth (WH), Jack Fulton (JF), Nancy Brown (NB), Diane Fulton (DF), Judy Fierstein (JYF), Gail Mahood (GM), Roger Brown (NB), Unknown (U?) Interviewer: Tom Martin (TM) Subject: With Nancy providing logistical support, Wes and Jack recount their thru-hike from Supai to the Hopi Salt Trail in 1968. Date of Interview: July 30, 2016 Method of Interview: At the home of Nancy and Roger Brown Transcriber: Anonymous Date of Transcription: March 9, 2020 Transcription Reviewers: Sue Priest, Tom Martin Keys: Grand Canyon thru-hike, Park Service, Edward Abbey, Apache Point route, Colin Fletcher, Harvey Butchart, Royal Arch, Jim Bailey TM: Today is July 30th, 2016. We're at the home of Nancy and Roger Brown in Livermore, California. This is an oral history interview, part of the Grand Canyon Historical Society Oral History Program. My name is Tom Martin. In the living room here, in this wonderful house on a hill that Roger and Nancy have, are Wes Hildreth and Gail Mahood, Jack and Diane Fulton, Judy Fierstein. I think what we'll do is we'll start with Nancy, we'll go around the room. If you can state your name, spell it out for me, and we'll just run around the room. NB: I'm Nancy Brown. RB: Yeah. Roger Brown. JF: Jack Fulton. WH: Wes Hildreth. GM: Gail Mahood. DF: Diane Fulton. JYF: Judy Fierstein. TM: Thank you. This interview is fascinating for a couple different things for the people in this room in that Nancy assisted Wes and Jack on a hike in Grand Canyon in 1968 from Supai to the Little Colorado River. -

![Yosemite National Park [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4323/yosemite-national-park-pdf-1784323.webp)

Yosemite National Park [PDF]

To Carson City, Nev il 395 ra T Emigrant Dorothy L ake Lake t s Bond re C Pass HUMBOLDT-TOIYABE Maxwell NATIONAL FOREST S E K Lake A L c i f i c IN a Mary TW P Lake Tower Peak Barney STANISLAUS NATIONAL FOREST Lake Buckeye Pass Huckleberry Twin Lakes 9572 ft EMIGRANT WILDERNESS Lake 2917 m HO O k N e V e O E r Y R C N Peeler A W Lake Crown C I Lake L D Haystack k e E Peak e S R r A Tilden W C TO N Schofield OT Rock Island H E Lake R Peak ID S Pass G E S s Styx l l Matterhorn Pass a F Peak Slide Otter ia Mountain Lake r e Burro h Green c Pass D n Many Island Richardson Peak a Lake L Lake 9877 ft R (summer only) IE 3010 m F E L Whorl Wilma Lake k B Mountain e B e r U N Virginia Pass C T O Virginia S Y N Peak O N Y A Summit s N e k C k Lake k A e a ic L r C e Kibbie N r d YO N C Lake n N A I C e ACK A RRICK J M KE ia K in N rg I i A r V T e l N k l i U e e p N O r C S M O Lundy Lake Y L Piute Mountain N L te I 10541 ft iu A T P L C I 3213 m T (summer only) Smedberg Benson k Lake e Pass k e e r e C r Benson C Lake k Lake ee Cree r Vernon k C r o e Upper n Volunteer cCab a M e McCabe l Mount Peak E Laurel k n r Lake Lake Gibson e u e N t r e McC C a R b R e L R a O O A ke Rodgers I s N PLEASANT A E H N L Lake I k E VALLEY R l Frog e i E k G K e E e a LA r R e T I r C r Table Lake V T T North Peak C Pettit Peak N A 10788 ft INYO NATIONAL FOREST O Y 3288 m M t ls Saddlebag al N s Roosevelt F A e Lake TIL a r Lake TILL ri C VALLEY (summer only) e C l h Lake Eleanor il c ilt n Mount Wapama Falls T a (summer only) N S Conness R I Virginia c HALL -

The Ancient Glaciers of the Sierra. John Muir

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons John Muir: A Reading Bibliography by Kimes John Muir Papers 12-1-1880 The Ancient Glaciers of the Sierra. John Muir Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/jmb Recommended Citation Muir, John, "The Ancient Glaciers of the Sierra." (1880). John Muir: A Reading Bibliography by Kimes. 192. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/jmb/192 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the John Muir Papers at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in John Muir: A Reading Bibliography by Kimes by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. '\ .. ~ ... \~~. ~' · 55° THE CALIFORNIAN. which she had arisen perfectly forgetful of me, my father's voice that I hear chiming always in of her marriage, of all but the haunting con my ears, eager and imperious? And in your scioiisness of a roo ted sorrow. Her father had face there is a look I have only observed late j died abroad, and her mother and sister returned ly, when you come to sit by me, that rem inds to find that the estate had melted away in the me of some one I have seen before. Who is .k . settlement, and now they were taking scholars. it? Who can it be?" Neil seemed to understand their position, but I fixed her eyes with mine. I will.ed her to any intellectual employment distressed her si nce know me, now at this supreine moment, with her iilness ; so, with the influence of her father's the passion of prayer. -

Yosemite Conservancy Spring.Summer 2012 :: Volume 03

YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY SPRING.SUMMER 2012 :: VOLUME 03 . ISSUE 01 Inspiring the Next Generation of Park Stewards INSIDE Youth Share Their Inspirational Stories Outdoor Adventures with a Conservancy Naturalist Expert Insights on Protecting Yosemite’s Bears Q&A With National Park Service Rangers COVER PHOTO: © COURTESY OF NPS. PHOTO: (RIGHT) © COURTESY OF NPS. OF NPS. (RIGHT) © COURTESY OF NPS. PHOTO: © COURTESY PHOTO: COVER MISSION Providing for Yosemite’s future is our passion. We inspire people to support projects and programs that preserve and protect Yosemite National Park’s resources and enrich the visitor experience. PRESIDENT’S NOTE YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY COUNCIL MEMBERS Youth in Yosemite: CHAIRMAN PRESIDENT & CEO John Dorman* Mike Tollefson* Changing Lives & VICE CHAIR VICE PRESIDENT Inspiring Stewardship Christy Holloway* & COO Jerry Edelbrock o you remember that first moment when you were spellbound by Yosemite? COUNCIL For me, it was visiting the park with Michael & Jeanne Adams Bob & Melody Lind Dmy family when I was five years old. I Lynda & Scott Adelson Sam & Cindy Livermore was mesmerized by the granite walls rising up Gretchen Augustyn Anahita & Jim Lovelace from the valley floor. Their sheer scale and Susan & Bill Baribault Lillian Lovelace Meg & Bob Beck Carolyn & Bill Lowman majesty continues to captivate me each and Suzy & Bob* Bennitt Dick Otter every time I visit Yosemite. David Bowman & Sharon & Phil* Gloria Miller Pillsbury At the Conservancy we understand the power of interacting with nature to bring Tori & Bob Brant Bill Reller Marilyn & Allan Brown Skip* & Frankie Rhodes about life-altering experiences. That’s why we are providing funding to cultivate the Marilyn & Don R. -

Yosemite Guide

G 83 after a major snowfall. major a after Note: Service to stops 15, 16, 17, and 18 may stop stop may 18 and 17, 16, 15, stops to Service Note: Third Class Mail Class Third Postage and Fee Paid Fee and Postage US Department Interior of the December 17, 2008 - February 17, 2009 17, February - 2008 17, December Guide Yosemite Park National Yosemite America Your Experience US Department Interior of the Service Park National 577 PO Box CA 95389 Yosemite, Experience Your America Yosemite National Park Vol. 34, Issue No.1 Inside: 01 Welcome to Yosemite 05 Programs and Events 06 Services and Facilities 10 Special Feature: Lincoln & Yosemite Dec ‘08 - Feb ‘09 Yosemite Falls. Photo by Christine White Loberg Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park December 17, 2008 - February 17, 2009 Yosemite Guide Experience Your America Yosemite National Park Yosemite Guide December 17, 2008 - February 17, 2009 Welcome to Yosemite Keep this Guide with You to Get the Most Out of Your Trip to Yosemite National Park information on topics such as camping and hiking. Keep this guide with you as you make your way through the park. Pass it along to friends and family when you get home. Save it as a memento of your trip. This guide represents the collaborative energy of the National Park Service, The Yosemite Fund, DNC Parks & Resorts at Yosemite, Yosemite Association, The Ansel Adams Gallery, and Yosemite Institute—organizations dedicated to Yosemite and to making Illustration by Lawrence W. Duke your visit enjoyable and inspiring (see page 11). -

Yosemite Today

G 83 Third Class Mail Class Third Postage and Fee Paid Fee and Postage US Department Interior of the Park National Yosemite America Your Experience June – July 2008 July – June Guide Yosemite US Department Interior of the Service Park National 577 PO Box CA 95389 Yosemite, Experience Your America Yosemite National Park Vol.33, Issue No.1 Inside: 01 Welcome to Yosemite 09 Special Feature: Yosemite Secrets 10 Planning Your Trip 14 Programs and Events Jun-Jul 2008Highcountry Meadow. Photo by Ken Watson Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park June 11 – July 22 Yosemite Guide Experience Your America Yosemite National Park Yosemite Guide June – July 2008 Welcome to Yosemite Keep this Guide with you to Get the Most Out of Your Trip to Yosemite National Park park, then provide more detailed infor- mation on topics such as camping and hiking. Keep this guide with you as you make your way through the park. Pass it along to friends and family when you get home. Save it as a memento of your trip. This guide represents the collaborative energy of the National Park Service, The Yosemite Fund, DNC Parks & Resorts at Yosemite, Yosemite Association, The Ansel Adams Gallery, and Yosemite Institute—organizations Illustration by Lawrence W. Duke dedicated to Yosemite and to making your visit enjoyable and inspiring (see The Yosemite page 23). Experience National parks were established to John Muir once wrote, “As long as I preserve what is truly special about live, I’ll hear waterfalls and birds and Giant Sequoias. NPS Photo America. -

Yosemap1.Pdf

Dorothy Lake Pass Emigrant il Lake ra T Dorothy Lake k Bond e e r Pass C S E Maxwell t K s A Lake L e r C y r r e Tower N h I C TW Peak STANISLAUS NATIONAL FOREST c Mary Barney fi Lake HUMBOLDT-TOIYABE i Buckeye Pass Lake Huckleberry c 9572 ft Lake a P 2917 m H EMIGRANT WILDERNESS Twin Lakes O NATIONAL FOREST O N V O Peeler E Y Lake R k N Crown e Lake e A k r rk C e W o Haystack C e F r I Rock Tilden Peak C AW t S TO L s O a Island T E Lake H D Schofield Matterhorn Styx Pass R s E I l D Peak l G Peak Pass D ia R a L r E F N E e Slide Otter I h F c Burro E Lake n Mountain Green E a Pass S Lake Richardson Peak (staffed L R S Many 9877 ft B Island intermittently) B 3010 m Lake k U Whorl e Wilma Lake T e r S Mountain C Virginia Pass N N O Virginia O k Y e Y e Peak Summit N r s N A C Lake e k k c C i A a r N L C O Kibbie Y d N CA Lake n AI N ERRICK a 167 M K e i K K r n C i A e rg J N l i I l V i A T p N S N k O U e re Y (staffed intermittently) O To C N Piute M A Carson City, Nev. -

Francis M. Fultz Papers LSC.0138

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5p3006g3 No online items Finding Aid for the Francis M. Fultz papers LSC.0138 Finding aid prepared by Manuscripts Division staff, 1990s; Kuhelika Ghosh, 2019 UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2019 April 01. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Francis M. LSC.0138 1 Fultz papers LSC.0138 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Francis M. Fultz papers Creator: Fultz, Francis M. (Francis Marion), 1857- Identifier/Call Number: LSC.0138 Physical Description: 105.8 Linear Feet(67 boxes, 38 oversize boxes, 1 oversize folder) Date (inclusive): 1845-1945 Abstract: Francis M. Fultz (1857-1948) was a school superintendent before becoming the director of conservation and reforestation in Los Angeles City Schools (1925-1932). He also lectured on subjects ranging from California, Hawaii and Yellowstone to camping, wildflowers and weeds. The collection consists of the manuscripts of 37 books and articles by Fultz, as well as carbons, early drafts, illustrations and research notes, books and periodicals containing articles by Fultz. The collection also contains runs of the Sierra Club bulletin, Trails and other periodicals, pamphlets and bound volumes, and lantern slides. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Conditions Governing Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE: Open for research. -

THE YOSEMITE BOOK by Josiah D. Whitney (1869)

Next: Chapter I: Introductory THE YOSEMITE BOOK by Josiah D. Whitney (1869) • Table of Contents • List of Photographs • [List of Illustrations appearing in The Yosemite Guide-Book (1870)] • Chapter I: Introductory • Chapter II: General • Chapter III: The Yosemite Valley • Chapter IV: The High Sierra • Chapter IV: The High Sierra [additional material from The Yosemite Guide-Book (1870)] • Chapter V: The Big Trees • Map of the Yosemite Valley... by C. King and J. T. Gardner (1865). • Map of a portion of the Sierra Nevada adjacent to the Yosemite Valley by Chs. F. Hoffman and J. T. Gardner (1863-1867). Introduction Josiah D. Whitney, 1863 California Geological Survey, December 1863: Chester Averill, assistant, William M. Gabb, paleontologist, William Ashburner, field assistant, Josiah D. Whitney, State Geologist, Charles F. Hoffmann, topographer, Clarence King, geologist and William H. Brewer, botanist (Bancroft Library). Josiah Dwight Whitney, Jr. was born 1819 in Massachusetts. He graduated at Yale and surveyed several areas in America and Europe as a geologist. In 1865, he was appointed professor of geology by Harvard in 1865 and received an honorary doctorate from Yale in 1870. In 1860 Whitney was appointed state geologist of California in 1860. Whitney, along with William H. Brewer, Clarence King, Lorenzo Yates, and others, made an extensive survey of California, including the Sierra Nevada and Yosemite region. Some California legislators though his job was just discovering gold and mineral wealth in the state. Whitney would have none of that and conducted a thorough scientific survey of the state. He published a well-regarded six-volume series Geological Survey of California (1864 - 1870), and this excellent volume, The Yosemite Book, among others.