Carl Stone: Hello I'm Vicki Bennett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glories of the Japanese Music Heritage ANCIENT SOUNDSCAPES REBORN Japanese Sacred Gagaku Court Music and Secular Art Music

The Institute for Japanese Cultural Heritage Initiatives (Formerly the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies) and the Columbia Music Performance Program Present Our 8th Season Concert To Celebrate the Institute’s th 45 Anniversary Glories of the Japanese Music Heritage ANCIENT SOUNDSCAPES REBORN Japanese Sacred Gagaku Court Music and Secular Art Music Featuring renowned Japanese Gagaku musicians and New York-based Hōgaku artists With the Columbia Gagaku and Hōgaku Instrumental Ensembles of New York Friday, March 8, 2013 at 8 PM Miller Theatre, Columbia University (116th Street & Broadway) Join us tomorrow, too, at The New York Summit The Future of the Japanese Music Heritage Strategies for Nurturing Japanese Instrumental Genres in the 21st-Century Scandanavia House 58 Park Avenue (between 37th and 38th Streets) Doors open 10am Summit 10:30am-5:30pm Register at http://www.medievaljapanesestudies.org Hear panels of professional instrumentalists and composers discuss the challenges they face in the world of Japanese instrumental music in the current century. Keep up to date on plans to establish the first ever Tokyo Academy of Japanese Instrumental Music. Add your voice to support the bilingual global marketing of Japanese CD and DVD music masterpieces now available only to the Japanese market. Look inside the 19th-century cultural conflicts stirred by Westernization when Japanese instruments were banned from the schools in favor of the piano and violin. 3 The Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies takes on a new name: THE INSTITUTE FOR JAPANESE CULTURAL HERITAGE INITIATIVES The year 2013 marks the 45th year of the Institute’s founding in 1968. We mark it with a time-honored East Asian practice— ―a rectification of names.‖ The word ―medieval‖ served the Institute well during its first decades, when the most pressing research needs were in the most neglected of Japanese historical eras and disciplines— early 14th- to late 16th-century literary and cultural history, labeled ―medieval‖ by Japanese scholars. -

Words That Kill Rumours, Prejudice, Stereotypes and Myths Amongst the People of the Great Lakes Region of Africa

Words That Kill Rumours, Prejudice, Stereotypes and Myths Amongst the People of the Great lakes Region of Africa Words That Kill Rumours, Prejudice, Stereotypes and Myths Amongst the People of the Great lakes Region of Africa About International Alert International Alert is an independent peacebuilding organisation that has worked for over 20 years to lay the foundations for lasting peace and security in communities affected by violent conflict. Our multifaceted approach focuses both in and across various regions; aiming to shape policies and practices that affect peacebuilding; and helping build skills and capacity through training. Our regional work is based in the African Great Lakes, West Africa, the South Caucasus, Nepal, Sri Lanka, the Philippines and Colombia. Our thematic projects work at local, regional and international levels, focusing on cross-cutting issues critical to building sustainable peace. These include business and economy, gender, governance, aid, security and justice. We are one of the world’s leading peacebuilding NGOs with an estimated income of £8.4 million in 2008 and more than 120 staff based in London and our 11 field offices. ©International Alert 2008 All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or means, electronic, mechanical, photocoplying, recording or otherwise, without full attribution. Design, production, print and publishing consultants: Ascent Limited [email protected] Printed in Kenya This report would not have been possible without the generous financial support of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Bread for the World. Table of Contents 1. Foreword 5 2. -

Crinew Music Re Uoft

CRINew Music Re u oft SEPTEMBER 11, 2000 ISSUE 682 VOL. 63 NO. 12 WWW.CMJ.COM MUST HEAR Universal/NIP3.com Trial Begins With its lawsuit against MP3.com set to go inent on the case. to trial on August 28, Universal Music Group, On August 22, MP3.com settled with Sony the only major label that has not reached aset- Music Entertainment. This left the Seagram- tlement with MP3.com, appears to be dragging owned UMG as the last holdout of the major its feet in trying to reach a settlement, accord- labels to settle with the online company, which ing to MP3.com's lead attorney. currently has on hold its My.MP3.com service "Universal has adifferent agenda. They fig- — the source for all the litigation. ure that since they are the last to settle, they can Like earlier settlements with Warner Music squeeze us," said Michael Rhodes of the firm Group, BMG and EMI, the Sony settlement cov- Cooley Godward LLP, the lead attorney for ers copyright infringements, as well as alicens- MP3.com. Universal officials declined to corn- ing agreement allowing (Continued on page 10) SHELLAC Soundbreak.com, RIAA Agree Jurassic-5, Dilated LOS AMIGOS INVIWITI3LES- On Webcasting Royalty Peoples Go By Soundbreak.com made a fast break, leaving the pack behind and making an agreement with the Recording Word Of Mouth Industry Association of America (RIAA) on aroyalty rate for After hitting the number one a [digital compulsory Webcast license]. No details of the spot on the CMJ Radio 200 and actual rate were released. -

2016-Program-Book-Corrected.Pdf

A flagship project of the New York Philharmonic, the NY PHIL BIENNIAL is a wide-ranging exploration of today’s music that brings together an international roster of composers, performers, and curatorial voices for concerts presented both on the Lincoln Center campus and with partners in venues throughout the city. The second NY PHIL BIENNIAL, taking place May 23–June 11, 2016, features diverse programs — ranging from solo works and a chamber opera to large scale symphonies — by more than 100 composers, more than half of whom are American; presents some of the country’s top music schools and youth choruses; and expands to more New York City neighborhoods. A range of events and activities has been created to engender an ongoing dialogue among artists, composers, and audience members. Partners in the 2016 NY PHIL BIENNIAL include National Sawdust; 92nd Street Y; Aspen Music Festival and School; Interlochen Center for the Arts; League of Composers/ISCM; Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts; LUCERNE FESTIVAL; MetLiveArts; New York City Electroacoustic Music Festival; Whitney Museum of American Art; WQXR’s Q2 Music; and Yale School of Music. Major support for the NY PHIL BIENNIAL is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, and The Francis Goelet Fund. Additional funding is provided by the Howard Gilman Foundation and Honey M. Kurtz. NEW YORK CITY ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC FESTIVAL __ JUNE 5-7, 2016 JUNE 13-19, 2016 __ www.nycemf.org CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 DIRECTOR’S WELCOME 5 LOCATIONS 5 FESTIVAL SCHEDULE 7 COMMITTEE & STAFF 10 PROGRAMS AND NOTES 11 INSTALLATIONS 88 PRESENTATIONS 90 COMPOSERS 92 PERFORMERS 141 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA THE AMPHION FOUNDATION DIRECTOR’S LOCATIONS WELCOME NATIONAL SAWDUST 80 North Sixth Street Brooklyn, NY 11249 Welcome to NYCEMF 2016! Corner of Sixth Street and Wythe Avenue. -

Society for Ethnomusicology 58Th Annual Meeting Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology 58th Annual Meeting Abstracts Sounding Against Nuclear Power in Post-Tsunami Japan examine the musical and cultural features that mark their music as both Marie Abe, Boston University distinctively Jewish and distinctively American. I relate this relatively new development in Jewish liturgical music to women’s entry into the cantorate, In April 2011-one month after the devastating M9.0 earthquake, tsunami, and and I argue that the opening of this clergy position and the explosion of new subsequent crises at the Fukushima nuclear power plant in northeast Japan, music for the female voice represent the choice of American Jews to engage an antinuclear demonstration took over the streets of Tokyo. The crowd was fully with their dual civic and religious identity. unprecedented in its size and diversity; its 15 000 participants-a number unseen since 1968-ranged from mothers concerned with radiation risks on Walking to Tsuglagkhang: Exploring the Function of a Tibetan their children's health to environmentalists and unemployed youths. Leading Soundscape in Northern India the protest was the raucous sound of chindon-ya, a Japanese practice of Danielle Adomaitis, independent scholar musical advertisement. Dating back to the late 1800s, chindon-ya are musical troupes that publicize an employer's business by marching through the From the main square in McLeod Ganj (upper Dharamsala, H.P., India), streets. How did this erstwhile commercial practice become a sonic marker of Temple Road leads to one main attraction: Tsuglagkhang, the home the 14th a mass social movement in spring 2011? When the public display of merriment Dalai Lama. -

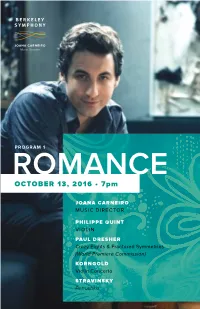

Berkeleysymphonyprogram2016

Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. We are now able to provide all funeral, cremation and celebratory services for our families and our community at our 223 acre historic location. For our families and friends, the single site combination of services makes the difficult process of making funeral arrangements a little easier. We’re able to provide every facet of service at our single location. We are also pleased to announce plans to open our new chapel and reception facility – the Water Pavilion in 2018. Situated between a landscaped garden and an expansive reflection pond, the Water Pavilion will be perfect for all celebrations and ceremonies. Features will include beautiful kitchen services, private and semi-private scalable rooms, garden and water views, sunlit spaces and artful details. The Water Pavilion is designed for you to create and fulfill your memorial service, wedding ceremony, lecture or other gatherings of friends and family. Soon, we will be accepting pre-planning arrangements. For more information, please telephone us at 510-658-2588 or visit us at mountainviewcemetery.org. Berkeley Symphony 2016/17 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 14 Season Sponsors 18 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 21 Program 25 Program Notes 39 Music Director: Joana Carneiro 43 Artists’ Biographies 51 Berkeley Symphony 55 Music in the Schools 57 2016/17 Membership Benefits 59 Annual Membership Support 66 Broadcast Dates Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of 69 Contact Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. -

San Francisco Cinematheque Program Notes

HllTyiinliiT'Ji r~.*«<' - - * k£ \ . - «• • 1 . ;•*-:! ---.- •. ..;' . ' „ I V / ' ' ' * " ' . '•,*:".•'•' . PROGRAM NOTES 1987 San Francisco Cinematheque A Project of the Board of Directors Staff The Foundation tor Art in Cinema 480 Potre'O Avenue Foundation tor Art in Cinema Scott Stark Steve Anner is supported in part with funds from: San Francisco. CA 94110 President P'ogram Director National Endowment for the Arts (415) 558-8129 Lon Argabnght David Gerstem California Arts Council Steve Fagm Administrative Director San Francisco Hotel Tax Fund Diane Kitchen San Francisco Foundation Jams Crystal Lipzin Ellen Zweig From the collection of the d Prelinger h u v JUibrary b t p San Francisco, California 2007 mi CINEMATOGRAPH PUBLICATION PARTY JANUARY 18, 1987 7:30 Show Net with Water by Melanie Berry, 1983, 3 min. , silent, super-8mm. Zone by Sokhi Wagner, 1981, 8 min., silent, super-8mm. Twig by Michael Mideke, 1966, 3 min., silent, 16mm. Mutiny by Abigail Child, 1982, 12 min., sound, 16mm. Baby in a Rage by Chuck Hudina, 1983, 9 min., silent, 16mm the ragged edges of the hollow by Edwin Cariati, 1984, 6 min., silent, 16mm. Frame Line by Gunvor Nelson, 1984, 22 min., sound, 16mm. 9:15 Show After God II by Leslie Singer, 1684, 3 min., silent, super-8mm. Foot 'Age Shoot Out by Kurt Kren, 1985, 3 min., sound, 16mm. Pearl and Puppet by Roger Jacoby, released 1982, 14 min., sound, 16mm. Deciduous by Lynn Kirby, 1982, 17 min., sound, 16mm. What's Out Tonight Is Lost by Phil Solomon, 1983, 9 min., silent, 16mm. Bopping the Great Wall of China Blue by Saul Levine, 1979, 5 min., sound, super-8mm. -

October 1994

Features AARON COMESS Album number two sees Spin Doctors drummer Aaron Comess laying down that slippery funky thing yet again. Not that Aaron has cut down on his extracurricular jazz work. Does this guy ever stop? • Teri Saccone 20 BOB MOSES The eccentric but unarguably gifted drummer who powered the first jazz-rock band is still breaking barriers. With a brand- new album and ever-probing style, Bob Moses explains why his "Simul-Circular Loopology" might be too dangerous in live doses. • Ken Micallef 26 HIGHLIGHTS OF MD's FESTIVAL WEEKEND '94 Where should we start? Simon Phillips? Perhaps "J.R." Robinson? Say, Rod Morgenstein? How about Marvin "Smitty" Smith...or David Garibaldi...maybe Chad Smith, Clayton Cameron, or Matt Sorum.... Two days, one stage, a couple thousand drummers, mega-prizes: No matter how you slice it, it's the mother of all drum shows, and we've got the photos to prove it! 30 Volume 18, Number 9 Cover Photo By Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 52 DRUM SOLOIST 8 UPDATE Max Roach: Bill Bruford, "Blues For Big Sid" David Garibaldi, TRANSCRIBED BY Dave Mancini, CRAIG SCOTT and Ray Farrugia of Junkhouse, plus News 76 HEALTH & SCIENCE 119 INDUSTRY Focal Dystonia: HAPPENINGS A Personal Experience BY CHARLIE PERRY WITH JACK MAKER DEPARTMENTS 42 PRODUCT CLOSE-UP 80 JAZZ 4 EDITOR'S Tama Iron Cobra DRUMMERS' OVERVIEW Bass Drum Pedals WORKSHOP BY ADAM BUDOFSKY Expanding The 6 READERS' 43 Tama Tension Watch Learning Process PLATFORM Drum Tuner BY JOHN RILEY BY ADAM BUDOFSKY 12 ASK A PRO 84 Rock 'N' 44 Vic Firth Ed Shaughnessy, American Concept Sticks JAZZ CLINIC Stephen Perkins, and BY WILLIAM F. -

SWP Strategy 2012

Project Review 2010/12 and Project Strategy 2012/14 www.singingwells.org What is the Singing Wells project? The Singing Wells project (SWP) is a collaboraon between Abubilla Music in London and Ketebul Music in Kenya, a non profit organisaon commiDed to iden9fying, preserving and promo9ng the diverse music tradi9ons of East Africa. The aim of the Singing Wells project is to record and document the unique music and dance of East Africa by travelling to rural villages throughout the region with a dedicated mobile recording ‘studio’ and a team of experienced music and video engineers and ethnomusicologists. The project includes the produc9on of new material called the Influences series - contemporary songs inspired and influenced by tradi9onal tribal music. Songs and videos produced by the Singing Wells project are made available to the widest possible audience through our Music Map of East Africa on the Singing Wells website: www.singingwells.org Fundraising for the Singing Wells project is managed By The AbuBilla Music FoundaFon, a UK registered charity (no: 1142173) RaFonale for the Singing Wells project East Africa is a region with a diverse cultural heritage. Its borders encompass a mul9tude of different ethnic groups, each with their own unique tradi9ons and histories, languages and dialects, religions and beliefs, ways of dressing, music and dance. Over 9me, many of these 9me-honoured prac9ces have been lost and there is liDle doubt that the pace of social, poli9cal and economic change today is in danger of obscuring the region’s tradi9onal cultural heritage. The importance of preserving music tradi9ons cannot be underes9mated. -

Traditional Knowledge in Refugee Camps

UNESCO activities for the support to youth centres and cultural groups in post-conflict refugee camps for transmitting intangible cultural knowledge in view of a sustainable repatriation UNESCO Field Office Dar es Salaam, CLT Traditional Knowledge in Refugee Camps The Case of Burundian Refugees in Tanzania Dr. Marie-Aude Fouéré Drum performance in Kanembwa refugee camp, Tanzania, at the beginning of a story-telling session Traditional Knowledge in Refugee Camps The Case of Burundian Refugees in Tanzania 2 Table of Contents Abbreviations 5 Glossary 6 Acknowledgments 7 Introduction 8 1. Traditional Knowledge in Refugee Camps in Tanzania 8 2. Historical Background 9 3. Repatriation and Reintegration of Refugees in Burundi 10 4. Kibondo Refugee Camps in Tanzania 11 I Traditional Knowledge in Burundian Refugee Camps 13 1. The Preservation of Burundian Traditional Knowledge 13 Informal Traditional Knowledge Formal Transmission of Performing Arts 2. Changes in Traditional Cultural Knowledge 17 Oral Traditions and Expressions Knowledge and Practices concerning Nature Cultural Norms: The Challenge of Male Position of Authority 3. Roots of Changes in Traditional Cultural Knowledge 20 The Genocide and the Experience of Exile Organization and Structure of Refugee Camps Humanitarian and Development Programs Globalisation in Refugee Camps Conclusion 23 II Socio-Cultural Challenges to Reintegration in Burundi 24 1. The First Stages of Return of Burundian Refugees 24 Facilitated Repatriation Arrival in the Colline (hill area) 2. A Two-Faceted Reintegration of Returnees 25 A Smooth Re-Adaptation to the Community An Obvious Reluctance to Discuss the Genocide Factors of Suspicion in the Colline : Former Rebels, Land Issue and International Aid 3. -

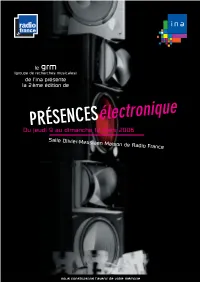

Doc Presences Electro.Pdf

le grm (groupe de recherches musicales) de l’ina présente la 2 ème édition de Du jeudi 9 au dimanche 12 Mars 2006 Salle Olivier-Messiaen Maison de Radio France nous construisons l’avenir de votre mémoire Du jeudi 9 au dimanche 12 mars 2006 salle Olivier-Messiaen Maison de Radio France Entrée libre dans la limite des places disponibles. Billet à retirer au guichet 1 heure avant le concert. > SAMEDI 11 MARS 20h00 – 1ère partie > JEUDI 9 MARS Robert HAMPSON alias MAIN Umbra (création) Antye GREIE alias AGF (création) 20h00 Yoshihiro HANNO alias RADIQ Fragments, Parallel timeless for it to tie (création) Bernard PARMEGIANI L’œil écoute (1970) - Le présent composé (1991) - Au gré du souffle, le son s’envole (création) 2ème partie 22h00 PAN SONIC (création) Amon TOBIN (création) Luc FERRARI Hétérozygote (1964) Pierre HENRY Variance dédiée à Luc Ferrari (création) Ryoji IKEDA (création) > DIMANCHE 12 MARS 16h00 > VENDREDI 10 MARS François DONATO The Lights of B. (2004) 20H00 Éliane RADIGUE Elemental II (2004) Kasper T. TOEPLITZ, basscomputer Régis RENOUARD LARIVIÈRE Errance essorante (2005) Michel WAISVISZ / Jan St WERNER In concert with very old and new electronic music instruments (création) 18H00 22H00 Marc CHALOSSE Paris, New York, Tokyo, Berck-Plage (création) Jon HASSELL / LIGHTWAVE / Michel REDOLFI Shift ! (création) Carl STONE Attari (création) Jon HASSELL, trompette acoustique & Extended Markus POPP alias OVAL (création) LIGHTWAVE : Christian WITTMAN & Christoph HARBONNIER, synthèses Kasper T. TOEPLITZ Lärmesmitte pour solo basscomputer (création) MICHEL REDOLFI, synthèses & direction - live processing, Arnaud MERCIER 2 3 la 2 ème édition du festival Imaginée par l’institut national de l’audiovisuel et Radio France Nous pourrions, en exergue citer les mots de Stockhausen : « Le son est un oiseau transparent », tant les artistes invités ont souhaité concentrer l’attention sur la seule écoute. -

Other Minds in Association with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program Presents Other Minds Festival 21 March 4

O M OTHER MINDS IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE DJERASSI RESIDENT ARTISTS PROGRAM PRESENTS OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL 21 MARCH 4 - MARCH 6, 2016 SFJAZZ CENTER SAN FRANCISCO 2 1 WELCOME FESTIVAL TO OTHER MINDS 21 OF NEW MUSIC The 21st Other Minds Festival is present- 2 Message from the Artistic Director ed by Other Minds in association with the 4 Exhibition & Silent Auction Djerassi Resident Artists Program and SFJAZZ Center. 13 Concert 1 17 Concert 2 All festival concerts take place at Robert N. Miner Auditorium in the SFJAZZ Center. 19 Concert 3 20 Other Minds 21 Featured Artist 26 Other Minds 21 Performers 35 Other Minds 21 Staff Bios 35 About Other Minds 36 Festival Supporters: A Gathering Of Other Minds 40 About The Festival This booklet © 2016 Other Minds, All rights reserved O MESSAGE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WELCOME BACK TO OTHER MINDS Words, by Phil Kline, incorporating the recorded voice of American writer William Burroughs. More Mvoices follow as Flux also gives us Michael Gordon’s intense mini-masterpiece The Sad Park, a So many long-term plans are coming together for this year’s Other Minds Festival that I’m filled with even more anticipation than usual. Our list of guest composers and performers is brimming with view of the 9/11 disaster as told by young children in New York City. Also inspired by 9/11 is the music talent, and it’s our good fortune to present them all at once to you at OM 21. Here they are, fresh for solo violin and film (Bill Morrison) Light Is Calling, which will be performed by Kate Stenberg.