Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The European Council Maastricht

THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL MAASTRICHT 23-24 MARCH 1981 Documents in the dossier include: Conclusions Session of the European Council Reproduced from The European Council Dossier ofthe Group ofthe European People s Party Luxembourg 1990 Maastricht European Council Reproduced from the Bulletin ofthe European Communities, No. 3/1981 Meeting of the European Council in Maastricht European Community News No. 11/1981 European Community Information Service Washington DC CONCLUSIONS OF THE SESSIONS OF TIlE EUROPEAN CODNCR.. (1975 - 1990) Maastric:ht, 23 and 24 March 1981 Session of the European Council Maastricht, 23 and 24 March 1981 Conclusions Economic and social situation The European Council devoted a considerable part of its meeting to a detailed and searching review of the present state of the European Community. There was Ui1animous agreement that in the present difficult economic conditions the Community remains an essential achievement and an indispensable instrument for limiting the ef- fects of the recession and bringing about the return, on a sound and stable .......;;S, of sustained eco- nomic growth and satisfactory levels of employment. To achieve this puIpose and reduce the level of inflation the European Council concluded that the continuation of prudent monetary policies, a healthy budgetary management, and the reorientation of public and private expenditure in the di- rection of productive investment are major elements. The European Council expressed the view that the reinforcement of the economic structure of the Member States requires an effort that must be maintained over a number of years and that short-term demand stimuli will turn out to be ineffective. The European Council welcomed the recent economic measures taken by the Governments of some member countries. -

The Hijacking of PK326 by Jeffrey Balkind

THE WORLD BANK GROUP ARCHIVES PUBLIC DISCLOSURE AUTHORIZED Folder Title: Notes and correspondence - Life and Death on a Tarmac - The Hijacking of PK326 by Jeffrey Balkind Folder ID: 30293587 Series: World Bank Group Field Coordinator security policy and planning Dates: 1/1/1981 – 12/31/1994 Fonds: Personal Papers of James L. Theodores ISAD Reference Code: WB IBRD/IDA WB_IBRD/IDA_109-02 Digitized: 2/13/2020 To cite materials from this archival folder, please follow the following format: [Descriptive name of item], [Folder Title], Folder ID [Folder ID], ISAD(G) Reference Code [Reference Code], [Each Level Label as applicable], World Bank Group Archives, Washington, D.C., United States. The records in this folder were created or received by The World Bank in the course of its business. The records that were created by the staff of The World Bank are subject to the Bank’s copyright. Please refer to http://www.worldbank.org/terms-of-use-earchives for full copyright terms of use and disclaimers. THE WORLD BANK Washington, D.C. © International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / International Development Association or The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org PUBLIC DISCLOSURE AUTHORIZED Arclir .. i~.. II III II /1111 /II /I IllI I IllII Ill III /I III ll/II ll I/ Iii <:. ~· 30293587 ··· ·· .. ·· A2016-001 0th # Notes and correspondence . Life er . 3 3970188 Jeffrey Ba/kind and Death on a Tarmac • The H" k' DECLASSIFIED !Jae ing of PK326 by Wll'Il . ,;~ STRICTION WBG Archives 202-667-7947 (H) ; 458-9116 1829- 19th, Street, N.W . -

Nov. 1974-Feb. 1949; #1-11

The materials listed in this document are available for research at the University of Record Series Number Illinois Archives. For more information, email [email protected] or search http://www.library.illinois.edu/archives/archon for the record series number. 24/1/0/30 Chancellor Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs Cope Action Records, 1974- Box 1: Nov. 1974-Feb. 1949; #1-11 Box 2: March 1979-March 1981; #12-27 Alphabetical list, by department Department Report # Date of Report A Administration, Higher, & Continuing Education, Dept. of 21 Sept. 1980 Advertising, Dept. of 11 Feb. 1979 Accountancy, Dept. of 28 May, 1981 Aeronautical & Astronautical Engineering, Dept. of 23 Jan. 1981 African Studies Program 15 March 1980 Agricultural Communications Office 30 June 1981 Agricultural Economics, Dept. of 4 Feb. 1976 Agricultural Engineering, Dept. of 6 July 1978 Agronomy, Dept. of 6 July 1978 Animal Science, Dept. of 10 Feb. 1979 Anthropology, Dept. of 3 Nov. 1975 Architecture 32 Jan. 1982 Art & Design, Dept. of 14 Aug. 1979 Asian Studies Center 15 March 1980 Astronomy, Dept. of 22 Nov. 1980 B Biochemistry, Dept. of 25 Feb. 1981 Botany, Dept of 27 March 1981 Business Administration, Dept. of 28 May 1981 C Ceramic Engineering, Dept. of 17 April 1980 Chemical Engineering, Dept. of 25 Feb. 1981 Chemistry, Dept. of 25 Feb. 1981 Civil Engineering, Dept. of 12 March 1979 Classics, Dept. of 27 Feb. 1981 Computer Science, Dept. of 12 March 1979 Comparative Literature Program 29 May 1981 D Dairy Science, Dept. of 30 June 1981 Dance, Dept. of 14 Aug. 1979 24/1/0/30 2 E Ecology, Ethology, & Evolution, Dept. -

Country Term # of Terms Total Years on the Council Presidencies # Of

Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council Elected Members Algeria 3 6 4 2004 - 2005 December 2004 1 1988 - 1989 May 1988, August 1989 2 1968 - 1969 July 1968 1 Angola 2 4 2 2015 – 2016 March 2016 1 2003 - 2004 November 2003 1 Argentina 9 18 15 2013 - 2014 August 2013, October 2014 2 2005 - 2006 January 2005, March 2006 2 1999 - 2000 February 2000 1 1994 - 1995 January 1995 1 1987 - 1988 March 1987, June 1988 2 1971 - 1972 March 1971, July 1972 2 1966 - 1967 January 1967 1 1959 - 1960 May 1959, April 1960 2 1948 - 1949 November 1948, November 1949 2 Australia 5 10 10 2013 - 2014 September 2013, November 2014 2 1985 - 1986 November 1985 1 1973 - 1974 October 1973, December 1974 2 1956 - 1957 June 1956, June 1957 2 1946 - 1947 February 1946, January 1947, December 1947 3 Austria 3 6 4 2009 - 2010 November 2009 1 1991 - 1992 March 1991, May 1992 2 1973 - 1974 November 1973 1 Azerbaijan 1 2 2 2012 - 2013 May 2012, October 2013 2 Bahrain 1 2 1 1998 - 1999 December 1998 1 Bangladesh 2 4 3 2000 - 2001 March 2000, June 2001 2 Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council 1979 - 1980 October 1979 1 Belarus1 1 2 1 1974 - 1975 January 1975 1 Belgium 5 10 11 2007 - 2008 June 2007, August 2008 2 1991 - 1992 April 1991, June 1992 2 1971 - 1972 April 1971, August 1972 2 1955 - 1956 July 1955, July 1956 2 1947 - 1948 February 1947, January 1948, December 1948 3 Benin 2 4 3 2004 - 2005 February 2005 1 1976 - 1977 March 1976, May 1977 2 Bolivia 3 6 7 2017 - 2018 June 2017, October -

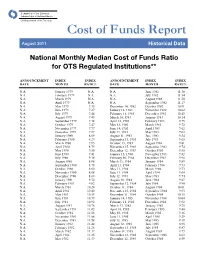

Historical Data

Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks US Department of the Treasury Cost of Funds Report August 2011 Historical Data National Monthly Median Cost of Funds Ratio for OTS Regulated Institutions** ANNOUNCEMENT INDEX INDEX ANNOUNCEMENT INDEX INDEX DATE MONTH RATE% DATE MONTH RATE% N.A. January 1979 N.A. N.A. June 1982 11.38 N.A. February 1979 N.A. N.A. July 1982 11.54 N.A. March 1979 N.A. N.A. August 1982 11.50 N.A. April 1979 N.A. N.A. September 1982 11.17 N.A. May 1979 7.35 December 14, 1982 October 1982 10.91 N.A. June 1979 7.27 January 12, 1983 November 1982 10.62 N.A. July 1979 7.44 February 11, 1983 December 1982 10.43 N.A. August 1979 7.49 March 14, 1983 January 1983 10.14 N.A. September 1979 7.38 April 12, 1983 February 1983 9.75 N.A. October 1979 7.47 May 13, 1983 March 1983 9.72 N.A. November 1979 7.77 June 14, 1983 April 1983 9.62 N.A. December 1979 7.87 July 13, 1983 May 1983 9.62 N.A. January 1980 8.09 August 11, 1983 June 1983 9.54 N.A. February 1980 8.29 September 13, 1983 July 1983 9.65 N.A. March 1980 7.95 October 13, 1983 August 1983 9.81 N.A. April 1980 8.79 November 15, 1983 September 1983 9.74 N.A. May 1980 9.50 December 12, 1983 October 1983 9.85 N.A. -

Nonrubber Footwear: U.S

NONRUBBER FOOTWEAR: U.S. PRODUCTION, EX.PORTS, IMPORTS FOR CONSUMPTION, PRODUCERS' PRICE INDEX, AND CONSUMER PRICE . INDEX FIRST CALENDAR ' QUARTER 1981 1' Rep()rt to the President on Investigation No. 332-93 Under Section 332 · of the Tariff Act of 1980 ,,.1 USITC PUBLICATION 1148 MAY 1981 United Statn International Trade Commlaalon I Washington, D.C. 20438 UNITED ST ATES INTERNATIONAL T·RADE COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Bill Alberger, Chairman Michael J. Calhoun, Vice Chairman Catherine Bedell · Paula Stern Kenneth R. Mason, Secretary to the Commission THIS 1£PORf WAS Pf£PAfED PRINCIPALLY BY J. GAIL BU~S TEXTILES, LEATHER PRODUCTS AND APPAREL DIVISION OFFICE OF INDUSTRIES NORRIS A. LYNCH, DIRECTOR Address all communications to Office of the Secretary · United States International Trade Commission Washington, D.C. 20436 C 0 N T E N T S Summary highlights of economic conditions in the nonrubber footwear industry in the first calendar quarter of 1981-------------------------- 1 Statistical Tables L Nonrubber footwear: U.S. production, imports for consumption, and apparent consumption, by months, January 1979-March 1981------ 3 2. Nonrubber footwear: Average number of employees, total and production workers, by months, January 1979-March 1981------------ 4 3. Unemployment rate for the leather and leather products industry (SIC 31), Producer Price Index for footwear (BLS code 043), and Consumer Price Index for footwear of leather and non- leather, by months, January 1979-March 1981----------------------- 5 4. Nonrubber footwear: U.S. production, imports for consumption, exports of domestic merchandise, apparent consumption, average number of employees, total and production workers, and unemployment rate, 1968-80---------------------------------------- 6 5. Nonrubber foot~ear: Quantity of U.S. -

Educational Attainment of Workers, March 1981

Special Labor Force Reports-Summaries Educational attainment comprising the largest part of the baby boom genera- of workers, March 1981 tion-the male-female difference in the proportion with some college narrowed substantially. Close to half of all workers in that age group had completed some college. ANNE MCDOUGALL YOUNG Participation rates More education has historically been associated with Employers continue to use education as one of the basic higher rates of labor force participation, a pattern that qualifications for hiring and promotion, and in recent persisted in March 1981 . College graduates had the years the educational level of workers has increased dra- highest labor force participation rates, and high school matically. In March 1981, there were almost as many dropouts, the lowest. (See table 2.) workers age 25 to 64 who had completed a year or more Participation rates for men have continued their his- of college as had ended their formal education with a torical drift downward among all age and educational high school diploma. (See table 1 .) Each of these two attainment groups except college graduates under age groups accounted for about 40 percent of the work 55 . This general trend among men has been observed force. As recently as 1970, only 26 percent of the work- over the past 25 years .5 Accounting in part for this ers had completed any college after high school.' (See ta- trend are more widely available disability and pension ble 2.) This change reflects primarily the coming of age benefits, which have made early retirement possible . of the more highly educated baby boom generation,z Persons in poor health or who have been out of work and, to a lesser extent, early retirement among older and for a number of months, have been the most likely to generally less educated workers. -

NELCHINA YEARLING MOOSE MORTALITY STUDY by Warren B

ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME JUNEAU, ALASKA STATE OF ALASKA Jay s. Hammond, Governor DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME Ronald 0. Skoog, Commissioner DIVISION ON G~ Ronald J. Somerville, Director Steven R. Peterson, Research Chiet NELCHINA YEARLING MOOSE MORTALITY STUDY by Warren B. Ballard Craig L. Gardner and Sterling D. Miller Volume II Federal Aid in Wildiife Restoration Projects w-.21-1 and W-21-~, Job 1.27R with Additional Support from the Alaska Power Authority Persons are free to use material in these reports for educational or informational purposes. However, since most reports treat only part of continuing studies, persons intending to use this material in scientific publications should obtain prior permission from the Department of Fish and Game. In all cases tentative conclusions should be identified as such in quotation, and due credit would be appreciated. (May 1982) ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME JUNEAU, ALASKA STATE OF ALASKA Jay S. Hammond, Governor DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME Ronald 0. Skoog, Commissioner DIVISION ON GAME Ronald J. Somerville, Director Steven R. Peterson, Research Chief NELCHINA YEARLING MOOSE MORTALITY STUDY by Warren B. Ballard Craig L. Gardner and Sterling D. Miller Volume II Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Projects W-21-1 and W-21-2, Job 1.27R with Additional Support from the Alaska Power Authority Persons are free to use material in these reports for educational or informational purposes. However, since most reports treat only part of continuing studies, persons intending to use this material in scientific publications should obtain prior permission from the Department of Fish and Game. -

Capital Punishment 1981 (Final Report), Privacy and Security Box 1240, Ann Arbor, Mich.4B106, (313/764-5199)

------'-----------_._----------_. u.s. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics .: .;~','-.,'.,?," ,t';•... ,. '. , ~"", ' •. 1.. ',."' " .. ,..... ',",. .' . 00", ' '.'.'.;' .. "'> " ~, ~ ... ~. '-'.,'C);. ~ Bureau of Justice Statistics reports National Prisoner Statistics Expend!~'Jre and employment (revised March 1983) BJS bulletins; Justice expenditure and employment In the Single copies are available free from the National Prisoners at midyear 1982, NCJ-84875. 11/82 U.S., 1979: Preliminary report. NCJ-73288, 1/81 Criminal JusHce Reference Service, Box 6000, Prisoners In 1981, NCJ-82262, 5/82 Expenditure and employment data for the Rockville, Md. 20850 (use NCJ number to order). Prisoners 1925-81, NCJ-85861. 12/82 criminal justice system, 1978, NCJ-68482 , 7/81 Postage and handling is charged for multiple Death-row prisoners 1981, NCJ-83191, 8/82 Trends In expenditure and employment data for the criminal justice systl'lm, 1971-77, copies (301/251-5595). Prisoners in State and Federal institutions on NCJ-57463, 1/80 Public-use tapes of 8JS data sets and other December 31,1980 (final report), NCJ-80520. criminal justice data are available from the Criminal 7/82 Justice Archive and Information Network, P.O. Capital punishment 1981 (final report), Privacy and security Box 1240, Ann Arbor, Mich.4B106, (313/764-5199). NCJ-88484. 4/83 Computer crime: 1979 survey ofinmates ofState correctional facilities Computer security techniques, National Crime Survey and 1979 census of State correctional facilities NCJ-84049, 9/82 Criminal victimization In the U.S.: (BJS bulletins); Electronic funds transfer systems and crime, 1900-81 changes based on new estimates Prisoners and drugs, NCJ-87575. 3/83 NCJ-83736. 9/82 (8JS technical report), NCJ-87577.3/83 Prisoners and alcohol, NCJ-S6223, 1/83 Legislative resource manual, NCJ-78890, 9/81 1980 (final report), NCJ-84015. -

ALFA OWNER INDEX: January 1981 Through December 1991

ALFA OWNER INDEX: January 1981 through December 1991 The entries in this index refer to a mix of long articles, semi - long news items, short letters, questions, answers, and even shorter tips. Emphasis was given to indexing technical information, but the racing, miniature, and historical articles were faithfully included. Some entries appeared in several parts, over several months, and are so noted. Where practical, a short descriptive note is included with the entry to aid as a guide for those who wish to order back issues. Index originally compiled by George Hanlon, AROC-NJ Note: This index is being revised and expanded during 2010. A - Montreal – Aug. 1987; June 1988 Alfa Experience (by Joe Benson) - Spider – Nov. 1981; July 1982; Jan.1984; Nov.1984; - Alfa Spirit – March 1981 March 1986; Dec. 1988; Jan. 1989; July 1990; April - Alfetta Report – Feb. 1981. March 1981, April 1981 1991 - Back Issues - A Resource – June 1981 - Sport 116 – June 1987 - New Opportunity (Alfetta upgrade with V6 components) - Sprint Speciale – July 1982 – May 1981 - Sprint Veloce – December 1989 - Oil Pressure – Jan. 1981 - Tipo 33 – July 1983, Feb. 1984 - Stealth Alfa – April 1981 - Turbo 75 – May 1987 Alfas In Scale (by Mike Hemsley) Alfa Romeo, Inc. (business decisions, marketing strategies - Alfa in Formula One – April 1981 and historical information) - Troubles in Lilliput – June 1981 - 75 Turbo – May 1987 - Where to Find Them – May 1981 - Belandi, G. – Feb. 1981 - White Metal Kit Building (Part 2) – Jan. 1981 - Bertone – Aug. 1988 - White Metal Kit Building (Part 3) – Feb. 1981 - Braden I – July 1991 - White Metal Kit Building (Part 4) – March. -

Cost of Funds Report (Historical)

Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks US Department of the Treasury Cost of Funds Report December 2011 Historical Data National Monthly Median Cost of Funds Ratio for OTS Regulated Institutions** ANNOUNCEMENT INDEX INDEX ANNOUNCEMENT INDEX INDEX DATE MONTH RATE% DATE MONTH RATE% N.A. January 1979 N.A. N.A. June 1982 11.38 N.A. February 1979 N.A. N.A. July 1982 11.54 N.A. March 1979 N.A. N.A. August 1982 11.50 N.A. April 1979 N.A. N.A. September 1982 11.17 N.A. May 1979 7.35 December 14, 1982 October 1982 10.91 N.A. June 1979 7.27 January 12, 1983 November 1982 10.62 N.A. July 1979 7.44 February 11, 1983 December 1982 10.43 N.A. August 1979 7.49 March 14, 1983 January 1983 10.14 N.A. September 1979 7.38 April 12, 1983 February 1983 9.75 N.A. October 1979 7.47 May 13, 1983 March 1983 9.72 N.A. November 1979 7.77 June 14, 1983 April 1983 9.62 N.A. December 1979 7.87 July 13, 1983 May 1983 9.62 N.A. January 1980 8.09 August 11, 1983 June 1983 9.54 N.A. February 1980 8.29 September 13, 1983 July 1983 9.65 N.A. March 1980 7.95 October 13, 1983 August 1983 9.81 N.A. April 1980 8.79 November 15, 1983 September 1983 9.74 N.A. May 1980 9.50 December 12, 1983 October 1983 9.85 N.A. -

Workers' Compensation in 1980: Summary of Major Enactments

Workers' compensation in 1980: summary of major enactments Broader coverage and levels of benefits received the most attention among the 46 jurisdictions which met during the year, although several States did set new standards for measuring hearing loss LAVERNE C. TINSLEY All but six State legislatures convened in 1980, resulting efits for total disability and death through automatic in enactment of 136 amendments to State workers' adjustments of maximum benefit levels linked to each compensation laws.' Twenty-three jurisdictions carried State's average weekly wage. (See table 1 .) over legislation introduced from 1979 to the 1980 ses- The percentage of the State weekly wage on which sions. Most amendments either revised coverage or in- benefits are based was raised from 100 to 150 percent in creased or supplemented weekly benefits. Nevada, from 60 to 100 percent in Kentucky, and from Twenty-two jurisdictions amended their coverage 72 to 75 percent in Kansas. The percentage of the laws. California extended coverage to off-duty peace of- worker's wage for determining weekly benefits was in- ficers and firefighters performing work-related duties creased from 66-2/3 to 70 percent in New Jersey . Ef- anywhere in the State. Colorado and Missouri broad- fective in 1981, maximum weekly benefits in Missouri ened coverage to include sheriffs and deputy sheriffs and will be based on a percentage of the State average week- Ohio extended coverage to jail inmates. ly wage rather than being a statutory amount . Maxi- Domestic employees employed by an employer for mum benefits were also increased statutorily in five 240 hours or more during a calendar quarter will be other jurisdictions.