Star Ocean: Till the End of Time; a Nietzschian Approach to Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

XENOGEARS JUMP by SJ-Chan & Abraxesanon

XENOGEARS JUMP By SJ-Chan & AbraxesAnon Image: SECTIONS IN YELLOW LIKE THIS HAVE NOT BEEN VETTED BY SJ SECTIONS IN GREEN LIKE THIS ARE BEING CONSIDERED SECTIONS IN BLUE LIKE THIS ARE RECENTLY MODIFIED BY SJ SECTIONS IN WHITE ARE THE ONLY BITS THAT ARE MOSTLY FINISHED Feel free to comment on anything, but if it’s in Yellow or Green, Abraxes wrote it, and I haven’t approved it yet. Oh, and if it’s in Black… it’s probably cut and pasted from a wiki. The continent of Ignas, in the northern hemisphere of our world. On this, the largest continent, a war has been raging between two countries for hundreds of years. In the north lies the Kislev Empire, in the south lies the desert kingdom of Aveh. The war has gone on for so long that people have forgotten the cause, knowing only the pointless cycle of hostility and tragedy. This chronic war obsession was soon to encounter a devastating change, thanks to the ‘Ethos’, an institution that preserves the world’s culture, repairing tools and weapons excavated from the ruins of an ancient civilization. Practically simultaneously, both Kislev and Aveh began to excavate their native ruins, seeking weapons from ancient technology and had the ‘Ethos’ repair the discoveries. The various weapons recovered greatly changed the form of warfare. The outcome of the battles between the two countries was no longer determined by man-to-man combat, but by ‘Gears’ - giant humanoid fighting machines - that were obtained from deep within the ruins. Inevitably, after many swings in the state of the war, Kislev gained the upper hand, in large part because of the superior quantity of resources buried within their ruins. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

11Eyes Achannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air

11eyes AChannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air Master Amaenaideyo Angel Beats Angelic Layer Another Ao No Exorcist Appleseed XIII Aquarion Arakawa Under The Bridge Argento Soma Asobi no Iku yo Astarotte no Omocha Asu no Yoichi Asura Cryin' B Gata H Kei Baka to Test Bakemonogatari (and sequels) Baki the Grappler Bakugan Bamboo Blade Banner of Stars Basquash BASToF Syndrome Battle Girls: Time Paradox Beelzebub BenTo Betterman Big O Binbougami ga Black Blood Brothers Black Cat Black Lagoon Blassreiter Blood Lad Blood+ Bludgeoning Angel Dokurochan Blue Drop Bobobo Boku wa Tomodachi Sukunai Brave 10 Btooom Burst Angel Busou Renkin Busou Shinki C3 Campione Cardfight Vanguard Casshern Sins Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Chaos;Head Chobits Chrome Shelled Regios Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai Clannad Claymore Code Geass Cowboy Bebop Coyote Ragtime Show Cuticle Tantei Inaba DFrag Dakara Boku wa, H ga Dekinai Dan Doh Dance in the Vampire Bund Danganronpa Danshi Koukousei no Nichijou Daphne in the Brilliant Blue Darker Than Black Date A Live Deadman Wonderland DearS Death Note Dennou Coil Denpa Onna to Seishun Otoko Densetsu no Yuusha no Densetsu Desert Punk Detroit Metal City Devil May Cry Devil Survivor 2 Diabolik Lovers Disgaea Dna2 Dokkoida Dog Days Dororon EnmaKun Meeramera Ebiten Eden of the East Elemental Gelade Elfen Lied Eureka 7 Eureka 7 AO Excel Saga Eyeshield 21 Fight Ippatsu! JuudenChan Fooly Cooly Fruits Basket Full Metal Alchemist Full Metal Panic Futari Milky Holmes GaRei Zero Gatchaman Crowds Genshiken Getbackers Ghost -

Understanding Computer Role-Playing Games

Understanding Computer Role-Playing Games A Genre Analysis Based on Gameplay Features in Combat Systems Christopher Dristig Stenström1 Staffan Björk2,3 1Chalmers University of Technology 2Gothenburg University 3The Interactive Institute Department of of Applied IT Department of Applied IT Lindholmsplatsen 1 412 96 Gotheburg SWEDEN 412 96 Gothenburg SWEDEN 417 56 Göteborg +46 (0)31-7721039 +46 (0)31-7721039 +46 (0)702-889759 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT viewed as a vital part – if not the core gameplay – of the role- A game genre as diverse as that of computer role-playing games playing genre. This is a stance differing from for example that of is difficult to overview. This poses challenges or both developers Wolf [32] which uses an inclusive strategy to compile genres and researchers to position their work clearly within the genre. within video games. However, that approach leaves the We present an overview of the genre based on clustering games motivation for specific subgenres difficult to understand from a with similar gameplay features. This allows a tracing of relations structural perspective and does not clearly show any potential between subgenres through their gameplay, and connecting this to relation between the subgenres. While limiting the perspective, concrete game examples. The analysis was done through using the choice of basing a subgenre specification on the gameplay gameplay design patterns to identify gameplay features and related to combat offers to present a subgenre classification focused upon the combat systems in the games. The resulting scheme with internal relations and a common method for cluster structure makes use of 321 patterns to create 37 different selection. -

The Evolving Heroine in Nintendo Adventure Games

The Princess and the Platformer: The Evolving Heroine in Nintendo Adventure Games Katharine Phelps Humanities 497W December 15, 2007 Just remember that my being a woman doesn't make me any less important! --Faris Final Fantasy V 1 The Princess and the Platformer: The Evolving Heroine in Nintendo Adventure Games Female characters, even as a token love interest, have been a mainstay in adventure games ever since Nintendo became a household name. One of the oldest and most famous is the princess of the Super Mario games, whose only role is to be kidnapped and rescued again and again, ad infinitum. Such a character is hardly emblematic of feminism and female empowerment. Yet much has changed in video games since the early 1980s, when Mario was born. Have female characters, too, changed fundamentally? How much has feminism and changing ideas of women in Japan and the US impacted their portrayal in console games? To address these questions, I will discuss three popular female characters in Nintendo adventure game series. By examining the changes in portrayal of these characters through time and new incarnations, I hope to find a kind of evolution of treatment of women and their gender roles. With such a small sample of games, this study cannot be considered definitive of adventure gaming as a whole. But by selecting several long-lasting, iconic female figures, it becomes possible to show a pertinent and specific example of how some of the ideas of women in this medium have changed over time. A premise of this paper is the idea that focusing on characters that are all created within one company can show a clearer line of evolution in the portrayal of the characters, as each heroine had her starting point in the same basic place—within Nintendo. -

Embodying the Game

Transcoding Action: Embodying the game Pedro Cardoso & Miguel Carvalhais ID+, Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Porto, Portugal. [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract this performance that is monitored and interpreted by the While playing a video game, the player-machine interaction is not game system, registering very specific data that is solely characterised by constraints determined by which sensors subordinated to the diverse kinds of input devices that are and actuators are embedded in both parties, but also by how their in current use. actions are transcoded. This paper is focused on that transcoding, By operating those input devices the player interacts with on understanding the nuances found in the articulation between the game world. In some games, for the player to be able to the player's and the system's actions, that enable a communication feedback loop to be established through acts of gameplay. This act in the game world, she needs to control an actor, an communication process is established in two directions: 1) player agent that serves as her proxy. This proxy is her actions directed at the system and, 2) system actions aimed at the representation in the game world. It is not necessarily her player. For each of these we propose four modes of transcoding representation in the story of the game. The player’s proxy that portray how the player becomes increasingly embodied in the is the game element she directly controls, and with which system, up to the moment when the player's representation in the she puts her actions into effect. -

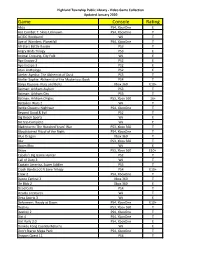

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

364 Gaminguistics: Proposing a Framework on The

Journal of Social Studies Education Research Sosyal Bilgiler Eğitimi Araştırmaları Dergisi 2019:10 (3),364-386 www.jsser.org Gaminguistics: Proposing a Framework on the Communication of Video Game Avatars Giyoto Giyoto1, SF. Luthfie Arguby Purnomo2, Lilik Untari3, SF. Lukfianka Sanjaya Purnama4 & Nur Asiyah5 Abstract This study attempts to construct a communication framework of video game avatars. Employing Aarseth’s textonomy, Rehak’s avatar’s life cycle, and Lury’s prosthetic culture avatar’s theories as the basis of analysis on fifty-five purposively selected games, this study proposes ACTION (Avatars, Communicators, Transmissions, Instruments, Orientations and Navigations). Avatars, borrowing Aarseth’s terms, are classifiable into interpretive, explorative, configurative, and textonic with four systems and sub classifications for each type. Communicators, referring to the participants involved in the communication with the avatars and their relationship, are classifiable into unipolar, bipolar, tripolar, quadripolar, and pentapolar. Transmissions, the ways in which communication is transmitted, are classifiable into restrictive verbal and restrictive non-verbal. Instruments, the graphical embodiment of communications, are realized into dialogue boxes, non-dialogue boxes, logs, expressions, movements and emoticons. Orientations, the methods the game spatiality employs to direct the movement of the avatars, are classifiable into dictative and non-dictative. Navigations, the strategies avatars perform regarding with the information saving system of the games, are classifiable into experimental and non-experimental. Departing from this ACTION, analysts are able to employ this formula as an approach to reveal how the avatars utilize their own ‘linguistics’ to communicate, out of the linguistics benefited by humans. Keywords: framework of communication, game avatars, game studies, video games, prosthetic culture. -

09062299296 Omnislashv5

09062299296 omnislashv5 1,800php all in DVDs 1,000php HD to HD 500php 100 titles PSP GAMES Title Region Size (MB) 1 Ace Combat X: Skies of Deception USA 1121 2 Aces of War EUR 488 3 Activision Hits Remixed USA 278 4 Aedis Eclipse Generation of Chaos USA 622 5 After Burner Black Falcon USA 427 6 Alien Syndrome USA 453 7 Ape Academy 2 EUR 1032 8 Ape Escape Academy USA 389 9 Ape Escape on the Loose USA 749 10 Armored Core: Formula Front – Extreme Battle USA 815 11 Arthur and the Minimoys EUR 1796 12 Asphalt Urban GT2 EUR 884 13 Asterix And Obelix XXL 2 EUR 1112 14 Astonishia Story USA 116 15 ATV Offroad Fury USA 882 16 ATV Offroad Fury Pro USA 550 17 Avatar The Last Airbender USA 135 18 Battlezone USA 906 19 B-Boy EUR 1776 20 Bigs, The USA 499 21 Blade Dancer Lineage of Light USA 389 22 Bleach: Heat the Soul JAP 301 23 Bleach: Heat the Soul 2 JAP 651 24 Bleach: Heat the Soul 3 JAP 799 25 Bleach: Heat the Soul 4 JAP 825 26 Bliss Island USA 193 27 Blitz Overtime USA 1379 28 Bomberman USA 110 29 Bomberman: Panic Bomber JAP 61 30 Bounty Hounds USA 1147 31 Brave Story: New Traveler USA 193 32 Breath of Fire III EUR 403 33 Brooktown High USA 1292 34 Brothers in Arms D-Day USA 1455 35 Brunswick Bowling USA 120 36 Bubble Bobble Evolution USA 625 37 Burnout Dominator USA 691 38 Burnout Legends USA 489 39 Bust a Move DeLuxe USA 70 40 Cabela's African Safari USA 905 41 Cabela's Dangerous Hunts USA 426 42 Call of Duty Roads to Victory USA 641 43 Capcom Classics Collection Remixed USA 572 44 Capcom Classics Collection Reloaded USA 633 45 Capcom Puzzle -

Sailor Mars Meet Maroku

sailor mars meet maroku By GIRNESS Submitted: August 11, 2005 Updated: August 11, 2005 sailor mars and maroku meet during a battle then fall in love they start to go futher and futher into their relationship boy will sango be mad when she comes back =:) hope you like it Provided by Fanart Central. http://www.fanart-central.net/stories/user/GIRNESS/18890/sailor-mars-meet-maroku Chapter 1 - sango leaves 2 Chapter 2 - sango leaves 15 1 - sango leaves Fanart Central A.whitelink { COLOR: #0000ff}A.whitelink:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.whitelink:visited { COLOR: #0000ff}A.BoxTitleLink { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:hover { COLOR: #465584; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:visited { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.normal { COLOR: blue}A.normal:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.normal:visited { COLOR: #000020}A { COLOR: #0000dd}A:hover { COLOR: #cc0000}A:visited { COLOR: #000020}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper { COLOR: #ff0000}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:hover { COLOR: #ffaaaa}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:visited { COLOR: #cc0000}.BoxTitleColor { COLOR: #000000} picture name Description Keywords All Anime/Manga (0)Books (258)Cartoons (428)Comics (555)Fantasy (474)Furries (0)Games (64)Misc (176)Movies (435)Original (0)Paintings (197)Real People (752)Tutorials (0)TV (169) Add Story Title: Description: Keywords: Category: Anime/Manga +.hack // Legend of Twilight's Bracelet +Aura +Balmung +Crossovers +Hotaru +Komiyan III +Mireille +Original .hack Characters +Reina +Reki +Shugo +.hack // Sign +Mimiru -

Towards Accessibility of Games: Mechanical Experience, Competence Profiles and Jutsus

Towards Accessibility of Games: Mechanical Experience, Competence Profiles and Jutsus. Abstract Accessibility of games is a multi-faceted problem, one of which is providing mechanically achievable gameplay to players. Previous work focused on adapting games to the individual through either dynamic difficulty adjustment or providing difficulty modes; thus focusing on their failure to meet a designed task. Instead, we look at it as a design issue; designers need to analyse the challenges they craft to understand why gameplay may be inaccessible to certain audiences. The issue is difficult to even discuss properly, whether by designers, academics or critics, as there is currently no comprehensive framework for that. That is our first contribution. We also propose challenge jutsus – structured representations of challenge descriptions (via competency profiles) and player models. This is a first step towards accessibility issues by better understanding the mechanical profile of various game challenges and what is the source of difficulty for different demographics of players. 1.0 Introduction Different Types of Experience When discussing, critiquing, and designing games, we are often concerned with the “player experience” – but what this means is unsettled as games are meant to be consumed and enjoyed in various ways. Players can experience games mechanically (through gameplay actions), aesthetically (through the visual and audio design), emotionally (through the narrative and characters), socially (through the communities of players), and culturally (through a combination of cultural interpretations and interactions). Each aspect corresponds to different ways that the player engages with the game. We can map the different forms of experience to the Eight Types of Fun (Hunicke, LeBlanc, & Zubek, 2004) (Table 1). -

Juuma Houkan Accele Brid Ace Wo Nerae! Acrobat Mission

3X3 EYES - JUUMA HOUKAN ACCELE BRID ACE WO NERAE! ACROBAT MISSION ACTRAISER HOURAI GAKUEN NO BOUKEN! - TENKOUSEI SCRAMBLE AIM FOR THE ACE! ALCAHEST THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN - LETHAL FOES ANGELIQUE ARABIAN NIGHTS - SABAKU NO SEIREI-O ASHITA NO JOE CYBERNATOR BAHAMUT LAGOON BALL BULLET GUN BASTARD!! BATTLE SOCCER - FIELD NO HASHA ANCIENT MAGIC - BAZOO! MAHOU SEKAI BING BING! BINGO BISHOUJO SENSHI SAILOR MOON - ANOTHER STORY SAILOR MOON R BISHOUJO SENSHI SAILOR MOON SUPER S - FUWA FUWA PANIC BRANDISH 2 - THE PLANET BUSTER BREATH OF FIRE II - SHIMEI NO KO BS CHRONO TRIGGER - MUSIC LIBRARY CAPTAIN TSUBASA III - KOUTEI NO CHOUSEN CAPTAIN TSUBASA V - HASH NO SHOUGOU CAMPIONE CARAVAN SHOOTING COLLECTION CHAOS SEED - FUUSUI KAIROKI CHOU MAHOU TAIRIKU WOZZ CHRONO TRIGGER CLOCK TOWER CLOCKWERX CRYSTAL BEANS FROM DUNGEON EXPLORER CU-ON-PA SFC CYBER KNIGHT CYBER KNIGHT II - CHIKYUU TEIKOKU NO YABOU CYBORG 009 DAI 3 JI SUPER ROBOT WARS DAI 4 JI SUPER ROBOT WARS DAIKAIJ MONOGATARI DARK HALF DARK LAW - THE MEANING OF DEATH DER LANGRISSER DIGITAL DEVIL STORY 2 - SHIN MEGAMI TENSEI II DONALD DUCK NO MAHOU NO BOUSHI DORAEMON 4 DO RE MI FANTASY - MILON NO DOKIDOKI DAIBOUKEN DOSSUN! GANSEKI BATTLE DR. MARIO DRAGON BALL Z - HYPER DIMENSION DRAGON BALL Z - CHOU SAIYA DENSETSU DRAGON BALL Z - SUPER BUTOUDEN DRAGON BALL Z - SUPER BUTOUDEN 3 DRAGON BALL Z - SUPER GOKUDEN - TOTSUGEKI HEN DRAGON BALL Z - SUPER GOKUDEN - KAKUSEI HEN DRAGON BALL Z - SUPER SAIYA DENSETSU DRAGON QUEST I AND II DRAGON QUEST III - SOSHITE DENSETU E... DRAGON QUEST V - TENKUU NO HANAYOME