The Green Web a Union for World Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Living World

1 The Living World MultipleChoiceQuestions (MCQs) 1 As we go from species to kingdom in a taxonomic hierarchy, the number of common characteristics (a)willdecrease (b)willincrease (c)remainsame (d) mayincreaseordecrease Ans. (a) Lower the taxa, more are the characteristic that the members within the taxon share. So, lowest taxon share the maximum number of morphological similarities, while its similarities decrease as we move towards the higher hierarchy, i.e., class, kingdom. Thus,restoftheoptionareincorrect. 2 Which of the following ‘suffixes’ used for units of classification in plants indicates a taxonomic category of ‘family’? (a) − Ales (b) − Onae (c) − Aceae (d) − Ae K ThinkingProcess Biological classification of organism is a process by which any living organism is classified into convenient categories based on some common observable characters. The categoriesareknownas taxons. Ans. (c) The name of a family, a taxon, in plants always end with suffixes aceae, e.g., Solanaceae, Cannaceae and Poaceae. Ales suffix is used for taxon ‘order’ while ae suffix is used for taxon ‘class’ and onae suffixesarenotusedatallinanyofthetaxons. 3 The term ‘systematics’ refers to (a)identificationandstudyoforgansystems (b)identificationandpreservationofplantsandanimals (c)diversityofkindsoforganismsandtheirrelationship (d) studyofhabitatsoforganismsandtheirclassification K ThinkingProcess The planet earth is full of variety of different forms of life. The number of species that are named and described are between 1.7-1.8 million. As we explore new areas, new organisms are continuously being identified, named and described on scientific basis of systematicslaiddownbytaxonomists. 1 2 (Class XI) Solutions Ans. (c) The word systematics is derived from Latin word ‘Systema’ which means systematic arrangement of organisms. Linnaeus used ‘Systema Naturae’ as a title of his publication. -

The Main Feature This Month Describes a Very FRONT COVER Exciting Place - One of the Most Exciting European Otter (Lutra Lutra)

THE INTERNATIONAL WILDLIFE MAGAZINE Vol. 17 No. 4 April 1975 The main feature this month describes a very FRONT COVER exciting place - one of the most exciting European otter (Lutra lutra). places in the world, in fact. The Gunung Photo by Hans Reinhard/Bruce Colernan Leuser must represent one of the front rank of vital areas that conservationists must save, for all sorts of reasons. It is also a place that appeals because it is 150 The Great Wildlife still unexplored and unknown. Markus Borner Photographic Adventure told me when I was there last summer that 153 Birdwatcher at Large there were - and are - no adequate maps of the Gunung Leuser region. The most recent 154 Longnecks and Humpbacks was one prepared from American satellite Harry Frauca photographs. But it turned out to be 157 Into the Unknown inaccurate. So little known was the area that he even discovered a great rift valley in the Markus Bomer centre of the reserve, whose existence had been 166 Search for India's Grey Wolf unsuspected. S. P. Shahi Markus was involved specifically in the fate of the Sumatran rhino, but he was also 170 The Rooftop Gun concerned - through his project investigations Patricia M ol1aghan - with the wildlife of Sumatra generally. Working side by side with him were two other 173 A Brighter Future for the Polar Bear? Swiss zoologists; their project was to Colin Wyatt rehabilitate confiscated orang-utans. This makes a warm and fascinating story in itself, and we 176 The Latin Skin Trade are planning to publish a feature on it in a Fe/ipe Benavides future issue. -

Science, Observation and Entertainment: Competing Visions of Postwar British Natural History Television, 1946-1967

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery Science, Observation and Entertainment: Competing Visions of Post-war British Natural History Television 1946 – 1967 Dr. Gail Davies G. Davies (2000) 'Science, observation and entertainment: competing visions of post- war British natural history television, 1946-1967' Ecumene, 7 (4): 432-459 1 Abstract Popular culture is not the endpoint for the communication of fully developed scientific discourses; rather it constitutes a set of narratives, values and practices with which scientists have to engage in the heterogeneous processes of scientific work. In this paper I explore how one group of actors, involved in the development of both post-war natural history television and the professionalisation of animal behaviour studies, manage this process. I draw inspiration from sociologists and historians of science, examining the boundary work involved in the definition and legitimation of scientific fields. Specifically, I chart the institution of animal ethology and natural history filmmaking in Britain through developing a relational account of the co-construction of this new science and its public form within the media. Substantively, the paper discusses the relationship between three genres of early natural history television, tracing their different associations with forms of public science, the spaces of the scientific field and the role of the camera as a tool of scientific observation. Through this analysis I account for the patterns of co-operation and divergence in the broadcasting and scientific visions of nature embedded in the first formations of the Natural History Unit of the British Broadcasting Corporation. -

The Living World Components & Interrelationships Management

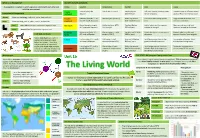

What is an Ecosystem? Biome’s climate and plants An ecosystem is a system in which organisms interact with each other and Biome Location Temperature Rainfall Flora Fauna with their environment. Tropical Centred along the Hot all year (25-30°C) Very high (over Tall trees forming a canopy; wide Greatest range of different animal Ecosystem’s Components rainforest Equator. 200mm/year) variety of species. species. Most live in canopy layer Abiotic These are non-living, such as air, water, heat and rock. Tropical Between latitudes 5°- 30° Warm all year (20-30°C) Wet + dry season Grasslands with widely spaced Large hoofed herbivores and Biotic These are living, such as plants, insects, and animals. grasslands north & south of Equator. (500-1500mm/year) trees. carnivores dominate. Flora Plant life occurring in a particular region or time. Hot desert Found along the tropics Hot by day (over 30°C) Very low (below Lack of plants and few species; Many animals are small and of Cancer and Capricorn. Cold by night 300mm/year) adapted to drought. nocturnal: except for the camel. Fauna Animal life of any particular region or time. Temperate Between latitudes 40°- Warm summers + mild Variable rainfall (500- Mainly deciduous trees; a variety Animals adapt to colder and Food Web and Chains forest 60° north of Equator. winters (5-20°C) 1500m /year) of species. warmer climates. Some migrate. Simple food chains are useful in explaining the basic principles Tundra Far Latitudes of 65° north Cold winter + cool Low rainfall (below Small plants grow close to the Low number of species. -

Mava Annual Report 2016

MAVA ANNUAL REPORT 2016 2016 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL Our Mission We conserve biodiversity for the benefit of people and nature by funding, mobilising and strengthening our partners and the conservation community. Our Values UNIFYING EMPOWERING FLEXIBLE PERSEVERING LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT AND THE DIRECTOR GENERAL Dear Friends It is with tremendous pleasure that we present our new Annual Report bringing you stories of conservation challenge and success from 2016. As well as a review of some of the year’s highlights, we pay tribute to our founder, the late Luc Hoffmann, present an overview of our 2016-2022 strategy, and introduce our work on impact and sustainability. Inside, we discover how the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is accessing, combining and disbursing finance from large donors in the Mediterranean and nurturing civil society groups born of the Arab Spring; applaud BirdLife’s Alcyon project for its critical mapping of Important Bird Areas (IBAs) in coastal West Africa; learn about MAVA’s Ecological Infrastructure programme seeking to boost the restoration of natural habitats in canton Vaud; and recognise the vital work of the Green Economy Coalition’s Measure What Matters initiative and the need to adopt the health of people and planet as our yardstick of progress. We also profile and celebrate more conservation heroes: Maher Mahjoub, IUCN North Africa Programme Coordinator, for his ability to bring hope to remote and insecure communities and bridge worlds in the Maghreb; Jean Malack, Park Guard in the Saloum Delta National Park in Senegal, for his extraordinary navigation skills and dedication to the Alcyon project; Lukas Indermauer, leader of WWF’s Living Alpine Rhine campaign, for his commitment to taking on the grave threat of hydropower; and Oshani Perera at the International Institute for Sustainable Development for her innovative engagement with the world of development finance and foreign direct investment. -

How to Save the World STRATEGY for WORLD CONSERVATION

How to save the world STRATEGY FOR WORLD CONSERVATION Robert Allen AX Kogan Page IUCN UNEP WW This book is based on the World Conservation Strategy prepared by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), with the advice, cooperation and financial assistance of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Illustrations: Patrick Virolle Cartoons and cover design: Oliver Duke Copyright ; I UCN-UNEP-WWE 1980 All rights reserved First published 1980 by Kogan Page Limited 120 Pentonvitte Road London NI 9JN Printed in England by MCCorquodale (Newton) Ltd.. Newton-le-Willows, Lancashire. ISBN 0 85038 314 5 (Hb) iSBN (}85038 3153 (Pb) Contents Foreword 7 Preface 9 I. Why the world needs saving now and how it can be done 11 Securing the food supply 33 Forests: saving the saviours 53 Learning to live on planel sea 71 Coming to terms with our fellow species 93 Getting organized: a strategy for conservation 121 Implementing the strategy 145 Foreword Sir Peter Scott Chairman, World Wildlife Fund The World Conservation Strategy, on which this book is based, represents several firsts in nature conservation. it is the first time that governments, non-governmental organizations and experts throughout the world have been involved in preparing a global conservation document. it is the first time that it has been clearly shown how conservation can contribute to the development objectives of governments, industry, commerce, organized labour and the professions. And it is the first time that development has been suggested as a major means of achieving conservation, instead of being viewed as an obstruction to it. -

Ernst Haeckel's Embryological Illustrations

Pictures of Evolution and Charges of Fraud Ernst Haeckel’s Embryological Illustrations By Nick Hopwood* ABSTRACT Comparative illustrations of vertebrate embryos by the leading nineteenth-century Dar- winist Ernst Haeckel have been both highly contested and canonical. Though the target of repeated fraud charges since 1868, the pictures were widely reproduced in textbooks through the twentieth century. Concentrating on their first ten years, this essay uses the accusations to shed light on the novelty of Haeckel’s visual argumentation and to explore how images come to count as proper representations or illegitimate schematics as they cross between the esoteric and exoteric circles of science. It exploits previously unused manuscripts to reconstruct the drawing, printing, and publishing of the illustrations that attracted the first and most influential attack, compares these procedures to standard prac- tice, and highlights their originality. It then explains why, though Haeckel was soon ac- cused, controversy ignited only seven years later, after he aligned a disciplinary struggle over embryology with a major confrontation between liberal nationalism and Catholicism—and why the contested pictures nevertheless survived. INETEENTH-CENTURY IMAGES OF EVOLUTION powerfully and controversially N shape our view of the world. In 1997 a British developmental biologist accused the * Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge, Free School Lane, Cambridge CB2 3RH, United Kingdom. Research for this essay was supported by the Wellcome Trust and partly carried out in the departments of Lorraine Daston and Hans-Jo¨rg Rheinberger at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. My greatest debt is to the archivists of the Ernst-Haeckel-Haus, Jena: the late Erika Krauße gave generous help and invaluable advice over many years, and Thomas Bach, her successor as Kustos, provided much assistance with this project. -

Palgrave Studies in Environmental Policy and Regulation

Palgrave Studies in Environmental Policy and Regulation Series Editor Justin Taberham London, UK The global environment sector is growing rapidly, as is the scale of the issues that face the environment itself. The global population is estimated to exceed 9 billion by 2050. New patterns of consumption threaten natu- ral resources, food and energy security and cause pollution and climate change. Policy makers and investors are responding to this in terms of support- ing green technology as well as developing diverse regulatory and policy measures which move society in a more ‘sustainable’ direction. More recently, there have been moves to integrate environmental policy into general policy areas rather than having separate environmental policy. This approach is called Environmental Policy Integration (EPI). The series will focus primarily on summarising present and emerging policy and regulation in an integrated way with a focus on interdisciplinary approaches, where it will fill a current gap in the literature. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/15053 Brian Joseph McFarland Conservation of Tropical Rainforests A Review of Financial and Strategic Solutions Brian Joseph McFarland Windham, NH, USA Palgrave Studies in Environmental Policy and Regulation ISBN 978-3-319-63235-3 ISBN 978-3-319-63236-0 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63236-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017955811 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and trans- mission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

Media Release

Media Release Basel, 22 July 2016 Lukas (Luc) Hoffmann dies at the age of 93 On Thursday 21 July 2016, Dr Lukas (Luc) Hoffmann, grandson of Roche founder Fritz Hoffmann-La Roche and his wife, Adele, died at the age of 93. Luc Hoffmann was a member of the Board of Directors for over 40 years - from 1953 to 1996. He supported the company with great commitment from an expansion phase in the sixties and seventies to its entry into biotechnology and molecular diagnostics. Luc Hoffmann was a strong advocate for basic research, one of the prerequisites for Roche's success as a research-focused - organisation. A committed conservationist, Luc Hoffmann consistently created an awareness of social and environmental responsibilities. He was convinced that sustainability is important not just for the environment, but also – and equally – for Roche as an underlying principle; with this conviction, he was influential in developing and implementing Roche’s sustainability strategy. Luc Hoffmann, born 1923 as the son of Emanuel Hoffmann and Maja Hoffmann-Stehlin, studied zoology in Basel and received his doctorate in 1952. He married Daria Razumovsky (1925-2002) the following year, and together they had four children. From 1954, he devoted great effort to setting up the "Station biologique de la Tour du Valat" research centre in the Camargue (France) at the heart of a nature reserve, and made the centre’s management his lifelong project. He was also a founding member and Vice President of the WWF (1961–1988) and was actively involved in a host of other conservation and cultural projects. -

Histories of Protected Areas: Internationalisation of Conservationist Values and Their Adoption in the Netherlands Indies (Indonesia)

Histories of Protected Areas: Internationalisation of Conservationist Values and their Adoption in the Netherlands Indies (Indonesia) PAUL JEPSON* AND ROBERT J. WHITTAKER School of Geography and the Environment University of Oxford Mansfield Road, Oxford, OX1 3TB, UK *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT National parks and wildlife sanctuaries are under threat both physically and as a social ideal in Indonesia following the collapse of the Suharto New Order regime (1967–1998). Opinion-makers perceive parks as representing elite special interest, constraining economic development and/or indigenous rights. We asked what was the original intention and who were the players behind the Netherlands Indies colonial government policy of establishing nature ‘monu- ments’ and wildlife sanctuaries. Based on a review of international conservation literature, three inter-related themes are explored: a) the emergence in the 1860– 1910 period of new worldviews on the human-nature relationship in western culture; b) the emergence of new conservation values and the translation of these into public policy goals, namely designation of protected areas and enforcement of wildlife legislation, by international lobbying networks of prominent men; and 3) the adoption of these policies by the Netherlands Indies government. This paper provides evidence that the root motivations of protected area policy are noble, namely: 1) a desire to preserve sites with special meaning for intellectual and aesthetic contemplation of nature; and 2) acceptance that the human conquest of nature carries with it a moral responsibility to ensure the survival of threatened life forms. Although these perspectives derive from elite society of the American East Coast and Western Europe at the end of the nineteenth century, they are international values to which civilised nations and societies aspire. -

The Archaeology of Sulawesi Current Research on the Pleistocene to the Historic Period

terra australis 48 Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and Island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: Coastal Sites in Southern Volume 28: New Directions in Archaeological Science. New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) A. Fairbairn, S. O’Connor and B. Marwick (2008) Volume 2: Ol Tumbuna: Archaeological Excavations in the Eastern Volume 29: Islands of Inquiry: Colonisation, Seafaring and the Central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Archaeology of Maritime Landscapes. G. Clark, F. Leach Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: The Geography and and S. O’Connor (2008) Ecology of Traffic in the Interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 30: Archaeological Science Under a Microscope: Studies in Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. B. Egloff (1979) Residue and Ancient DNA Analysis in Honour of Thomas H. Loy. M. Haslam, G. Robertson, A. Crowther, S. Nugent Volume 5: The Great Kartan Mystery. R. Lampert (1981) and L. Kirkwood (2009) Volume 6: Early Man in North Queensland: Art and Archaeology Volume 31: The Early Prehistory of Fiji. G. Clark and in the Laura Area. A. Rosenfeld, D. Horton and J. Winter A. -

2016 Baseball MG Intro Pages.Indd

A PROGRAM STEEPED IN TRADITION, ARMY BASEBALL ENTERS THE 2016 SEASON LOOKING TO RETURN TO THE PINNACLE OF THE PATRIOT LEAGUE. ARMY BOASTS SEVEN PATRIOT LEAGUE TOURNAMENT TITLES AND SIX NCAA REGIONAL APPEARANCES. WWW.GOARMYSPORTS.COM WEST POINT The U.S. Military Academy is renowned because of its historic and distinguished reputation as a military academy, and as a leading, progressive institution of higher education. Made legendary in books and movies produced over the years, the academy’s “Long Gray Line” of graduates includes some of our nation’s most famous and influential men: Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee, Thomas “Stone- wall” Jackson, George S. Patton, Omar Bradley, Douglas MacArthur, Dwight Eisenhower and Norman Schwarzkopf. Because of this superb education and leadership experience, West Point graduates historically have been sought for high-level civilian and military leadership positions. Their numbers include two U.S. presidents, several ambassadors, state governors, legislators, judges, cabinet members, educa- tors, astronauts and corporate executives. Today, West Point continues to provide hundreds of young men and women the unique opportunity to develop physically, ethically and intellectually while building a foundation for an exciting, chal- lenging and rewarding career as an Army officer in the service of our nation. Cadets have much more responsibility in running the Academy than students in most other colleges or universities. It adds to the leadership experience. Cadets succeed at West Point because of the support they receive from the staff and faculty. After all, many faculty members are West Point graduates and understand the challenge cadets face on a daily basis.