A Memorial Destroyed: Loyola, Quinta Normal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Variability of Particulate Matter (PM10) in Santiago, Chile by Phase of the Maddenejulian Oscillation (MJO)

Atmospheric Environment 81 (2013) 304e310 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Atmospheric Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/atmosenv Variability of particulate matter (PM10) in Santiago, Chile by phase of the MaddeneJulian Oscillation (MJO) Kelsey M. Ragsdale a, Bradford S. Barrett a, *, Anthony P. Testino b a Oceanography Department, U.S. Naval Academy, 572C Holloway Rd., Annapolis, MD 21401, USA b Nuclear Power Training Unit, U.S. Navy, USA highlights Variability of surface PM10 by MJO phase was explored for winter months. During phases 4, 5 and 7, PM10 levels in Santiago were above normal. During phases 1 and 2, PM10 levels in Santiago were below normal. Supporting variability was found for multiple atmospheric parameters. article info abstract Article history: Topographical, economical, and meteorological characteristics of Santiago, Chile regularly lead to Received 10 May 2013 dangerously high concentrations of particulate matter (PM10) in the city during winter months. Although Received in revised form the city has suffered from poor air quality for at least the past forty years, variability of PM10 in Santiago 3 September 2013 on the intraseasonal time scale had not been examined prior to this study. The MaddeneJulian Oscil- Accepted 5 September 2013 lation (MJO), the leading mode of atmospheric intraseasonal variability, modulates precipitation and circulation on a regional and global scale, including in central Chile. In this study, surface PM10 con- Keywords: centrations were found to vary by phase of the MJO. High PM concentrations occurred during phases 4, MaddeneJulian oscillation 10 Particulate matter 5 and 7, and low concentrations of PM10 occurred during phases 1 and 2. -

Quinta Normal Matucana Pudahuel Quinta Normal Gruta De Lourdes Av

Learn about the routes nearby this station 109 406 422 426 505 507 508 513 Maipú Cantagallo La Reina La Dehesa Las Parcelas Grecia Las Torres José Arrieta Quinta Normal Matucana Pudahuel Quinta Normal Gruta de Lourdes Av. Mapocho Gruta de Lourdes Gruta de Lourdes Estación Central Quinta Normal Sn. Pablo-Matucana Est. Central-Alameda Compañía-Pza. Italia Est. Central-Av. España Compañía-Pza. Italia Compañía-Pza. Italia Cam. a Melipilla Est. Central-Alameda Alameda-Portugal Av. Providencia Av. Salvador Pque. O'Higgins Av. Salvador-Av. Grecia Av. Salvador 1 5 de Abril Av. Providencia Av. Irarrázaval Av. Las Condes Av. Irarrázaval Av. Matta-Av. Grecia Jorge Monckeberg Av. Irarrázaval Pza. de Maipú Av. Las Condes Hospital Militar Cantagallo Av. Las Parcelas Estadio Nacional Las Torres Plaza Egaña Villa San Luis Cantagallo Villa La Reina La Dehesa Río Claro Muni. Peñalolén Av. Departamental J. Arrieta-Río Claro 6 PA1 Quinta Normal J16 B26 B28 J01 J02 J05 Estación Central Estación Central Quinta Normal Quinta Normal U.L.A. U.L.A. Costanera Sur Panamericana Plaza Renca San Pablo San Francisco Salvador Gutiérrez Hosp. Félix Bulnes Puente Bulnes Hosp. Félix Bulnes Neptuno-Av. Carrascal Neptuno Gruta de Lourdes Radal Matucana Av. Mapocho Hosp. Félix Bulnes José Joaquín Pérez Av. San Pablo Gruta de Lourdes Quinta Normal Matucana Av. San Pablo Quinta Normal Matucana Quinta Normal Hosp. San Juan de Dios Quinta Normal Quinta Normal Esperanza Quinta Normal Estación Central Estación Central Hosp. San Juan de Dios Hosp. San Juan de Dios U.L.A. U.L.A. 2 4 expreso expreso J01 J02 J05 J16 313e 313e Pudahuel Sur Enea Costanera Sur Costanera Sur Estación Central Quilicura Santo Domingo Quinta Normal Maipú Matucana San Ignacio Gral. -

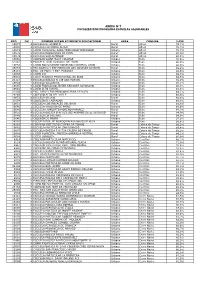

Rbd Dv Nombre Establecimiento

ANEXO N°7 FOCALIZACIÓN PROGRAMA ESCUELAS SALUDABLES RBD DV NOMBRE ESTABLECIMIENTO EDUCACIONAL AREA COMUNA %IVE 10877 4 ESCUELA EL ASIENTO Rural Alhué 74,7% 10880 4 ESCUELA HACIENDA ALHUE Rural Alhué 78,3% 10873 1 LICEO MUNICIPAL SARA TRONCOSO TRONCOSO Urbano Alhué 78,7% 10878 2 ESCUELA BARRANCAS DE PICHI Rural Alhué 80,0% 10879 0 ESCUELA SAN ALFONSO Rural Alhué 90,3% 10662 3 COLEGIO SAINT MARY COLLEGE Urbano Buin 76,5% 31081 6 ESCUELA SAN IGNACIO DE BUIN Urbano Buin 86,0% 10658 5 LICEO POLIVALENTE MODERNO CARDENAL CARO Urbano Buin 86,0% 26015 0 ESC.BASICA Y ESP.MARIA DE LOS ANGELES DE BUIN Rural Buin 88,2% 26111 4 ESC. DE PARV. Y ESP. PUKARAY Urbano Buin 88,6% 10638 0 LICEO 131 Urbano Buin 89,3% 25591 2 LICEO TECNICO PROFESIONAL DE BUIN Urbano Buin 89,5% 26117 3 ESCUELA BÁSICA N 149 SAN MARCEL Urbano Buin 89,9% 10643 7 ESCUELA VILLASECA Urbano Buin 90,1% 10645 3 LICEO FRANCISCO JAVIER KRUGGER ALVARADO Urbano Buin 90,8% 10641 0 LICEO ALTO JAHUEL Urbano Buin 91,8% 31036 0 ESC. PARV.Y ESP MUNDOPALABRA DE BUIN Urbano Buin 92,1% 26269 2 COLEGIO ALTO DEL VALLE Urbano Buin 92,5% 10652 6 ESCUELA VILUCO Rural Buin 92,6% 31054 9 COLEGIO EL LABRADOR Urbano Buin 93,6% 10651 8 ESCUELA LOS ROSALES DEL BAJO Rural Buin 93,8% 10646 1 ESCUELA VALDIVIA DE PAINE Urbano Buin 93,9% 10649 6 ESCUELA HUMBERTO MORENO RAMIREZ Rural Buin 94,3% 10656 9 ESCUELA BASICA G-N°813 LOS AROMOS DE EL RECURSO Rural Buin 94,9% 10648 8 ESCUELA LO SALINAS Rural Buin 94,9% 10640 2 COLEGIO DE MAIPO Urbano Buin 97,9% 26202 1 ESCUELA ESP. -

Gobernador Regional Región Metropolitana De Santiago Segundo Doblez

GOBERNADOR REGIONAL REGIÓN METROPOLITANA DE SANTIAGO SEGUNDO DOBLEZ FORMA : TIPO C (7-8 LISTAS) 26x23cm REGIÒN: METROPOLITANA ELECCIÓN: GORE AMF - ECZ GOBERNADORES REGIONALES 2021 PRIMER DOBLEZ REGION METROPOLITANA DE SANTIAGO CUARTO CUARTO DOBLEZ SERIE NNSV DOBLEZ SERVICIO ELECTORAL S L E A R R V - CO I O LES NV CI T A EN N° P N° C CI C O E I IO E L N L E N U E O A C I T M L IC - O E R V S R S A E E C L S L REPUBLICANOS FRENTE AMPLIO O A XO. XS. N N L S A O T I R S I T E O G R T 0 U E V C R Y E I C E S L N I E E O R 0000000 T 0000000 O E E O I S D L C - A I E G N O R E B C V T R O E S R L A R O T C E L E O I C I V R E S PARTIDO REPUBLICANO DE CHILE COMUNES 200 ROJO EDWARDS SILVA 201 KARINA LORETTA OLIVA PEREZ XX. CHILE VAMOS XZ. ECOLOGISTAS E INDEPENDIENTES EVOLUCION POLITICA PARTIDO ECOLOGISTA VERDE 202 CATALINA PAROT DONOSO 203 NATHALIE JOIGNANT PACHECO TERCER TERCER DOBLEZ DOBLEZ YA. HUMANICEMOS CHILE YN. UNIDAD CONSTITUYENTE PARTIDO HUMANISTA PARTIDO DEMOCRATA CRISTIANO 204 PABLO ANTONIO ANDRES MALTES BISKUPOVIC 205 CLAUDIO ORREGO LARRAIN ZB. UNION PATRIOTICAFACSÍMILZX. REGIONALISTAS VERDES UNION PATRIOTICA FEDERACION REGIONALISTA VERDE SOCIAL 206 FRESIA MONICA QUILODRAN RAMOS 207 RICARDO JAVIER MARTINEZ VALENCIA GR C REGION METROPOLITAN.indd 1 06-03-21 17:57 SEGUNDO DOBLEZ PRIMER DOBLEZ CONVENCIONALES CONSTITUYENTES PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS AIMARA SEGUNDO DOBLEZ 26 DE ALTO X 26,5 DE ANCHO FORMA PO-B - PK PRIMER DOBLEZ 2021 QUINTO QUINTO DOBLEZ DOBLEZ CONVENCIONALES CONSTITUYENTES Y CANDIDATOS PARITARIOS SERIE NNSV Nº ALTERNATIVOS DE PUEBLOS -

Hyatt Place Santiago/Vitacura Opens in Chile

Hyatt Place Santiago/Vitacura Opens in Chile 7/15/2014 The opening marks the first Hyatt Place hotel in Chile and on the South American continent CHICAGO--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Jul. 15, 2014-- Hyatt Hotels Corporation (NYSE: H) and HPV S.A. today announced the opening of Hyatt Place Santiago/Vitacura in the city of Santiago, Chile. The opening marks the second Hyatt- branded hotel in Santiago and introduces the Hyatt Place brand to Chile and the South American continent. The first Hyatt Place hotel outside the United States debuted in Central America with the 2012 opening of Hyatt Place San Jose/Pinares in Costa Rica. The Hyatt Place brand has since grown its brand presence in Latin America and the Caribbean with locations in Puerto Rico, Mexico and now Chile. Expansion is set to continue in the region later this year with anticipated Hyatt Place hotel openings in Mexico and Panama. Hyatt Place Santiago/Vitacura. Guestroom with Andes Mountain View. (Photo: Business Wire) As Chile continues to cement its rank of being one of the best places to do business in Latin America, backed by its 2013 designation as such by The World Bank, the country is an important business and leisure market for Hyatt. The opening of Hyatt Place Santiago/Vitacura is an important step in Hyatt’s growth in strategic gateway and regional markets throughout Latin America. “Hyatt’s history in Chile spans more than 20 years, beginning when Grand Hyatt Santiago welcomed its first guests,” said Myles McGourty , senior vice president of operations, Latin America & Caribbean for Hyatt. -

Doubletree by Hilton Santiago-Vitacura, 18Th Floor Av

DoubleTree by Hilton Santiago-Vitacura, 18th Floor Av. Vitacura 2727, Las Condes, Santiago, CHILE Day 1 - Tuesday 19 March Time Topic Speaker 0800-0830 Registration 0830-0850 Welcome and Safety Briefing Montes, SOARD 0850-0920 AFOSR International and SOARD Andersen, SOARD 0920-0940 Interactions between Cold Rydberg Atoms Marcassa, U Sao Paulo, BRA Two-photon Spectroscopy in Organic 0940-1000 Mendonca, U Sao Paulo, BRA Materials and Polymers 1000-1030 BREAK Metrology and Orbital Angular Momentum 1030-1050 U'Ren, UNAM, MEX Correlations in Two-photon Sources Optical and Magnetic Properties of 1050-1110 Maze, PUC Santiago, CHL Quantum Emitters in Diamond Insulator-Metal Transition and 1110-1130 Kopelevich, UNICAMP, BRA Superconductivity in CuCi Neuromorphic Imaging with Event-based 1130-1210 Cohen, Western Sydney U, AUS Sensors Extreme Compressive All-sky Tracking 1210-1230 Vera, PUC Valporaiso, CHL Camera (XCATCAM 1230-1400 LUNCH 1400-1420 The Chilean Neuromorphic Initiative Hevia, PUC Santiago, CHL Spin-torque Nano-oscillators for Signal 1420-1440 Allende, U de Santiago de Chile Processing and Storing Fundamentals of Plasticity and Criticality in 1440-1500 Gonzalez, U Andres Bello, CHL Thermally Regulated Ion Channels Adaptive Neural Network Mimicking the 1500-1520 Perez-Acle, Fund. Ciencia y Vida, CHL Visual System of Mammal Page 1 of 4 Retina-based Visual Module for Navigation 1520-1540 Escobar, U Tech Fed Santa Maria, CHL in Complex Environments 1540-1600 A Novel Approach to Exchange Bias Kiwi, U de Chile, CHL 1600-1640 BREAK 1620-1640 Riboswitches and RNA Polymerase Blamey, Fundacion Biocencia, CHL RF Generation Using Nonlinear 1640-1700 Rossi, INPE, BRA Transmission Lines Multi-Scale Dynamic Failure Modeling of 1700-1720 Sollero, UNICAMP, BRA Heterogeneous Materials 1720-1740 Emotion and Trust Detection from Speech Ferrer, U Buenos Aires, ARG 1740-1800 Biocorrosion Vejar, FACh / CIDCA, CHL 1800 MEETING ADJOURN 1830 Drinks DoubleTree Bar Page 2 of 4 DoubleTree by Hilton Santiago-Vitacura Av. -

Irregularidades En Orden De Gravedad

Centro de Investigación Periodística - CIPER IRREGULARIDADES EN ORDEN DE GRAVEDAD Irregularidad Colegio Comuna Sostenedor 2010 Sostenedor 2011 Registrar presente alumnos que ya no pertenecen al establecimiento Detectada en 4 colegios: COLEGIO PARTICULAR ÑUÑOA ÑUÑOA SOCIEDAD EDUCACIONAL SAN ANDRES LIMITADA COLEGIO POLIVALENTE PROFESOR GUILLERMO GONZÁLEZ PROVIDENCIA ANNETTE ALICIA GONZALEZ GONZALEZ ESCUELA BASICA CIMAS DEL MAIPO SAN JOSE DE MAIPO SOCIEDAD EDUCACIONAL SENDEROS LIMITADA ESCUELA PARTICULAR LOCARNO LA CISTERNA ADRIANA SOFIA PUELMA LOYOLA Registra presente a alumnos ausentes Detectada en 356 colegios: COLEGIO EMPRENDER LARAPINTA (x3)(veces que se registró la misma falta ) LAMPA CORPORACION EDUCACIONAL Y CULT.EMPRENDER ESCUELA ESPECIAL PARTICULAR CAPULLITOS DE SOL (x3) MACUL MARIA JACQUELINE DIAZ FUENTES COLEGIO ASCENCION NICOL (x2) ESTACION CENTRAL CONGR.RELIG.HNAS DOMINICAS DEL ROSARIO CENTRO EDUCACIONAL RENCA (x2) RENCA SOCIEDAD ESCUELA INDUSTRIAL RENCA LTDA CENTRO EDUCACIONAL ALBERTO HURTADO (x2) QUINTA NORMAL FUNDACION ESTRELLA DEL MAR CENTRO EDUCACIONAL LARUN RAYUN (x2) PUENTE ALTO SOCIEDAD EDUC. LARUN RAYUN LTDA. COLEGIO EMELINA URRUTIA (x2) EL MONTE CONGR.MISIONERA SIERVAS ESPIRITU SANTO COLEGIO INSUME (x2) NUNOA VICTOR FRANCISCO AGUILERA VASQUEZ COLEGIO NUEVA AURORA DE CHILE (x2) RECOLETA COMPLEJO EDUC.NUEVA AURORA DE CHILE LTDA COLEGIO NUEVOS CASTAÑOS DE MAIPU ANEXO (x2) MAIPU ROSA ELENA CONEJEROS MALDONADO COLEGIO PARTICULAR FAMILIA DE NAZARETH (x2) LA FLORIDA COLEGIO FAMILIA DE NAZARETH LTDA. COLEGIO PARTICULAR ÑUÑOA (x2) NUNOA SOCIEDAD EDUCACIONAL SAN ANDRES LIMITADA COLEGIO PARTICULAR FUNCASE (x2) PUENTE ALTO FUND.CRISTIANA DE ACCION SOCIAL Y EDUC. COLEGIO PARTICULAR INSTITUTO O HIGGINS DE MAIPÚ (x2) MAIPU SOCIEDAD INSTITUTO OHIGGINS DE MAIPU S.A COLEGIO PARTICULAR SOCHIDES RENCA (x2) RENCA SOC.CHILENA DE EDUC.Y DES. -

Urban Ethnicity in Santiago De Chile Mapuche Migration and Urban Space

Urban Ethnicity in Santiago de Chile Mapuche Migration and Urban Space vorgelegt von Walter Alejandro Imilan Ojeda Von der Fakultät VI - Planen Bauen Umwelt der Technischen Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Ingenieurwissenschaften Dr.-Ing. genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsausschuss: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. -Ing. Johannes Cramer Berichter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Peter Herrle Berichter: Prof. Dr. phil. Jürgen Golte Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 18.12.2008 Berlin 2009 D 83 Acknowledgements This work is the result of a long process that I could not have gone through without the support of many people and institutions. Friends and colleagues in Santiago, Europe and Berlin encouraged me in the beginning and throughout the entire process. A complete account would be endless, but I must specifically thank the Programme Alßan, which provided me with financial means through a scholarship (Alßan Scholarship Nº E04D045096CL). I owe special gratitude to Prof. Dr. Peter Herrle at the Habitat-Unit of Technische Universität Berlin, who believed in my research project and supported me in the last five years. I am really thankful also to my second adviser, Prof. Dr. Jürgen Golte at the Lateinamerika-Institut (LAI) of the Freie Universität Berlin, who enthusiastically accepted to support me and to evaluate my work. I also owe thanks to the protagonists of this work, the people who shared their stories with me. I want especially to thank to Ana Millaleo, Paul Paillafil, Manuel Lincovil, Jano Weichafe, Jeannette Cuiquiño, Angelina Huainopan, María Nahuelhuel, Omar Carrera, Marcela Lincovil, Andrés Millaleo, Soledad Tinao, Eugenio Paillalef, Eusebio Huechuñir, Julio Llancavil, Juan Huenuvil, Rosario Huenuvil, Ambrosio Ranimán, Mauricio Ñanco, the members of Wechekeche ñi Trawün, Lelfünche and CONAPAN. -

Ranking Calidad De Servicio De Empresas Concesionarias De Transantiago

RANKING CALIDAD DE SERVICIO DE EMPRESAS CONCESIONARIAS DE TRANSANTIAGO Trimestre abril – junio 2017 20 El “Ranking de Calidad de Servicio de las Empresas Concesionarias de Transantiago”. Este informe tiene como objetivo hacer públicos los resultados de las mediciones, la evolución y el grado de cumplimiento de los estándares de frecuencia y regularidad. Estos estándares son exigidos a las empresas concesionarias de buses por el Ministerio de Transporte y Telecomunicaciones (MTT) a través del Directorio de Transporte Público Metropolitano (DTPM), ya que se trata de los indicadores con mayor impacto en la calidad de servicio hacia los usuarios. En esta vigésima edición del Ranking, se entregan los resultados correspondientes al segundo trimestre del año 2017 (abril – junio) junto a una visión comparativa respecto al mismo trimestre del año 2016, con el fin de poder analizar su evolución aislando el efecto de estacionalidad que pudiera existir en cada uno de los indicadores. ¶ FRECUENCIA Número de salidas de buses por tramo horario. ¶ REGULARIDAD Lapso de circulación entre buses. EMPRESAS OPERADORAS INVERSIONES ALSACIA SUBUS CHILE BUSES VULE EXPRESS DE SANTIAGO UNO METBUS REDBUS URBANO STP SANTIAGO El sistema de transporte público COLOR DISTINTIVO COLOR DISTINTIVO COLOR DISTINTIVO COLOR DISTINTIVO COLOR DISTINTIVO COLOR DISTINTIVO COLOR DISTINTIVO Celeste Azul Verde Naranjo Turquesa Rojo Amarillo integrado de Santiago está FLOTA BASE CONTRATADA FLOTA BASE CONTRATADA FLOTA BASE CONTRATADA FLOTA BASE CONTRATADA FLOTA BASE CONTRATADA FLOTA BASE -

Contrasting Seismic Risk for Santiago, Chile, from Near-Field And

Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-2019-30 Manuscript under review for journal Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discussion started: 11 March 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. Contrasting seismic risk for Santiago, Chile, from near-field and distant earthquake sources Ekbal Hussain1,2, John R. Elliott1, Vitor Silva3, Mabé Vilar-Vega3, and Deborah Kane4 1COMET, School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK 2British Geological Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, Environmental Science Centre, Keyworth, Nottingham, NG12 5GG, UK 3GEM Foundation, Via Ferrata 1, 27100 Pavia, Italy 4Risk Management Solutions, Inc., Newark, CA, USA Correspondence to: Ekbal Hussain ([email protected]) Abstract. More than half of all the people in the world now live in dense urban centres. The rapid expansion of cities, particu- larly in low-income nations, has enabled the economic and social development of millions of people. However, many of these cities are located near active tectonic faults that have not produced an earthquake in recent memory, raising the risk of losing the hard-earned progress through a devastating earthquake. In this paper we explore the possible impact that earthquakes can 5 pose to the city of Santiago in Chile from various potential near-field and distant earthquake sources. We use high resolution stereo satellite imagery and derived digital elevation models to accurately map the trace of the San Ramón Fault, a recently recognised active fault located along the eastern margins of the city. We use scenario based seismic risk analysis to compare and contrast the estimated damage and losses to the city from several potential earthquake sources and one past event, comprising i) rupture of the San Ramón Fault, ii) a hypothesised buried shallow fault beneath the centre of the city, iii) a deep intra-slab fault, 10 and iv) the 2010 Mw 8.8 Maule earthquake. -

I Parte Diagnostico Comunal

SUR Profesionales Consultores ______________________________________________________________________________________ Actualización PLADECO Comuna de El Bosque 2 I PARTE: DIAGNÓSTICO COMUNAL Equipo consultor SUR Profesionales Consultores Gracia Barrios Catherine Bórquez Cristián del Canto Elizabeth Guerrero Patricio Reyes Juan Carlos Scapini Mario Villalobos (Jefe de Proyecto) Mesa técnica municipal PLADECO 2010-2016: Mario Aravena Humberto Campos Cuadrao Paola Cisternas Lagomarsino Jorge Gajardo Jorge Núñez Rius Marcos Pérez Suazo SUR Profesionales Consultores ______________________________________________________________________________________ Actualización PLADECO Comuna de El Bosque 3 INDICE GENERAL CONTENIDO PAG. PRESENTACIÓN 04 1. ASPECTOS TERRITORIALES, URBANOS Y MEDIO AMBIENTE 05 2. ASPECTOS SOCIALES 27 3. ASPECTOS ECONÓMICOS, PRODUCTIVOS Y DE EMPLEO 44 4. SERVICIOS COMUNITARIOS 60 5. PRESUPUESTO E INVERSIÓN COMUNAL 114 6. CONCLUSIONES 118 7. TENDENCIAS Y DESAFIOS PARA EL DESARROLLO COMUNAL 131 8. EVALUACION DEL PERÍODO DEL PLADECO ANTERIOR 135 SUR Profesionales Consultores ______________________________________________________________________________________ Actualización PLADECO Comuna de El Bosque 4 PRESENTACIÓN El presente documento contiene un diagnóstico integrado de la situación actual de desarrollo de la comuna de El Bosque y del conjunto de avances experimentados en la última década en los ámbitos territoriales, sociales, económicos y culturales. En efecto, en la primera parte del diagnóstico se presentan los principales aspectos territoriales, urbanos y la situación de medio ambiente de la comuna. Posteriormente, se muestra un panorama general con los principales aspectos sociales y comunitarios. En esta parte se incorpora la situación de pobreza en la comuna y la evolución que ha experimentado la misma. Luego, se introducen los principales aspectos económicos, productivos y la situación de empleo, que incluye tanto la creación de empleos en la comuna como la ocupación de sus habitantes. -

Enel X, Metbus and BYD Open Latin America's First Exclusive Electric Bus

Media Relations PRESS T +56 2 26752746 RELEASE [email protected] ENEL X, METBUS AND BYD OPEN LATIN AMERICA’S FIRST FULLY ELECTRIC BUS ROUTE • The integration of 183 new electric buses makes Greater Santiago the first city in Latin America to implement a sustainable electric route, with a total of 285 zero- emission public transport units. • Additionally, with the goal of improving users’ travel experience, the new electric route includes innovative infrastructure items, with a number of cutting-edge bus stops that offer services such as LED lighting, information panels, and USB chargers. Santiago, October 15, 2019 – Enel X, Metbus, and BYD have opened Latin America’s first electric bus route, a comprehensive sustainable transport system that will feature 100% electric buses, making Chile the region’s leading country for electric transport. The event, attended by President Sebastián Piñera and Transport Minister Gloria Hutt, opened with an electric bus ride along the route, which links the districts of Ñuñoa and Peñalolén, stopping to inspect some of the high-technology stops built by Enel X, as a way of experiencing the route as passengers will. The project includes the implementation of 40 bus stops, which offer users a range of new services such as LED lighting, bicycle parking, information panels, and USB charging ports. The ride ended at Peñalolén electric bus terminal, where the opening ceremony was held in the presence of guests such as President Sebastián Piñera, Transport Minister Gloria Hutt, Enel Chile chairman Herman Chadwick, Enel Chile CEO Paolo Pallotti, Enel X Chile CEO Karla Zapata, Metbus chairman Juan Pinto, and BYD country manager for Chile Tamara Berríos.