The Honor of Translating the Tale of Genji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Works S11-1.Pub

Fall 2010-Spring 2011 The Official Arts Publication of Sauk Valley Community College TheThe WorksWorks honorable mention in student visual art contest (above): Carlow, Ireland by William Brown Fiction Poetry Visual Arts The Anne Horton Writing Award 2011 Film Review Contest The Works Editorial Staff . Sara Beets Elizabeth Conderman Cody Froeter Tessa Ginn Tracy Hand Steven Hoyle James Hyde Jamie Lybarger Lauren Walter David Waters Faculty Advisor . Tom Irish * * * * * Special thanks to SVCC’s Foundation, Student Government Association, and English Department 2 Table of Contents . POETRY: First Place: Human Cannibalization: A Study, by Lauren Walter . 4 Honorable Mention: At the End of the Wind, by Phil Arellano . 6 Doesn’t Feel Right, by Sara Beets . 7 Goodnight, by Hayleigh Covella . 8 Two Caves, by Corey Coomes . .10 Doesn’t Feel Right, by Tessa Ginn . 11 Speed Kills, by Corey Coomes . 12 Something About Bravery, by Lauren Walter . .13 In My Place, by Jamie Lybarger . 14 Oh Sweetie, Oh Please, by Hayleigh Covella . 16 Mortal, by Sara Beets . 17 Hot Tears of Love, by Len Michaels . 18 Unimpressed, by Hayleigh Covella . 19 Planet Mars-Population: Failure, by Sara Beets . 20 Seventh Sin: A Collection of Poetry, by Sara Beets , Tessa Ginn, and Lauren Walter . 22 FICTION: First Place: Emperor Onion, by Elizabeth Conderman . 32 Honorable Mention: Buried, by Lauren Walter . 35 The Legend of the Pipperwhill, by Brooke Ehlert. 38 MICHAEL JUSTIN, by Rebekah Megill . 40 Just Animals, by Nick Sobottka . 42 The FINAL CHAPTER of NICK CARTER: The Price, by Jason Hedrick . 44 Pleasant Dreams, by Len Michaels . 47 A Very Short Story About Fruit Snacks, by Tom Irish . -

Interaction Between Record Matching and Data Repairing

Interaction between Record Matching and Data Repairing Wenfei Fan1;2 Jianzhong Li2 Shuai Ma3 Nan Tang1 Wenyuan Yu1 1University of Edinburgh 2Harbin Institute of Technology 3Beihang University fwenfei@inf., ntang@inf., [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract cost: it costs us businesses 600 billion dollars each year [16]. Central to a data cleaning system are record matching and With this comes the need for data cleaning systems. As data repairing. Matching aims to identify tuples that re- an example, data cleaning tools deliver \an overall business fer to the same real-world object, and repairing is to make a value of more than 600 million GBP" each year at BT [31]. In database consistent by fixing errors in the data by using con- light of this, the market for data cleaning systems is grow- straints. These are treated as separate processes in current ing at 17% annually, which substantially outpaces the 7% data cleaning systems, based on heuristic solutions. This pa- average of other IT segments [22]. per studies a new problem, namely, the interaction between There are two central issues about data cleaning: ◦ record matching and data repairing. We show that repair- Recording matching is to identify tuples that refer to ing can effectively help us identify matches, and vice versa. the same real-world entity [17, 26]. ◦ To capture the interaction, we propose a uniform frame- Data repairing is to find another database (a candidate work that seamlessly unifies repairing and matching oper- repair) that is consistent and minimally differs from ations, to clean a database based on integrity constraints, the original data, by fixing errors in the data [4, 21]. -

Better Is Better Than More: Complexity, Economic Progress, and Qualitative Growth

Better is Better Than More Complexity, Economic Progress, and Qualitative Growth by Michael Benedikt and Michael Oden Center for Sustainable Development Working Paper Series - 2011(01) csd Center for Sustainable Development The Center for Sustainable Development Better is Better than More: Complexity, Economic Working Paper Series 2011 (01) Progress, and Qualitative Growth Better is Better than More: Complexity, Economic Progress, and Qualitative Growth Michael Benedikt Hal Box Chair in Urbanism Michael Oden Professor of Community & Regional Planning Table of Contents The University of Texas at Austin 1. Introduction, and an overview of the argument 2 © Michael Benedikt and Michael Oden 2. Economic growth, economic development, and economic progress 6 Published by the Center for Sustainable Development The University of Texas at Austin 3. Complexity 10 School of Architecture 1 University Station B7500 Austin, TX 78712 4. The pursuit of equity as a generator of complexity 21 All rights reserved. Neither the whole nor any part of this paper may be reprinted or reproduced or quoted 5. The pursuit of quality as a generator of complexity 26 in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other Richness of functionality 31 means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information Reliability/durability 32 storage or retrieval system, without accompanying full Attention to detail 33 bibliographic listing and reference to its title, authors, Beauty or “style” 33 publishers, and date, place and medium of publication or access. Generosity 36 Simplicity 37 Ethicality 40 The cost of quality 43 6. Quality and equity together 48 The token economy 50 7. -

The Nerevarine Chronicles

The Nerevarine Chronicles Peace and Prosperity The kingdom of Avalon had existed for nearly a millennium, enjoying peace and prosperity for many of those centuries. In the ebb and flow of time, the races of Avalon united when necessary to converge on a common foe. For the most part, however the dwarves and elves tended to themselves and let the humans, with their shorter life spans, micro-manage the kingdom. As was the custom among humans at the time, people were addressed first by their surname and then their given name. The family name had taken precedence some generations prior, when the Great Houses of Northwind took prominence. Each ruling family was designated as House so-and-so. It did not take long for the custom to trickle out to the human rulers in Dai-Rynn and Dormack. The Great Houses were sometimes referenced by the family crest. House Dagoth, who were worshippers of Pelor, sported a rising sun above a sword, and was commonly called the Sun-and-Sword. House Indoril was called the Moon-and-Star, after their crest, which resembled a tiny slice of the night sky. House Indoril followed Heironeous and the origin of their crest remains a mystery. After the events surrounding the Nerevarine Prophecies, however, this all but ended. Family names were held with honor and pride, but took no more importance over the individual than they had prior. The Great Houses stopped referring to each other as such and that era was left in the wake of these unfortunate events to fade only into the annals of history. -

LL-L5R Rules.Pdf

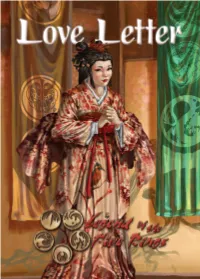

A few months ago, the Empress of Rokugan’s third child, Iweko Miaka, came of age. This instantly made her the most eligible maiden in the Empire, and prominent samurai from every clan and faction have set out to court her. Of course, in Rokugan marriage is a matter of duty and politics far more often than love, but the personal affection of a potential spouse can be a very effective tool in marriage negotiations. And when that potential spouse is an Imperial princess, her affection can be more influential than any number of political favors. 2 Of course, winning a princess’ heart is hardly an easy task in the tightly- monitored world of the Imperial Palace. The preferred tool of courtly romance in Rokugan is the letter, and every palace’s corridors are filled with the soft steps of servants carrying letters back and forth. But such letters can be intercepted by rivals or turned away by hostile guards. For a samurai to succeed in his suit, he will have to find ways of getting his own letters into Miaka’s hands – while blocking the similar efforts of rival suitors. 3 Object In the wake of many recent tragic events, Empress Iweko I has sought to bring a note of joy back to the Imperial City, Toshi Ranbo, by announcing the gempukku (coming- of-age) of her youngest child and only daughter, Iweko Miaka. Prominent samurai throughout the Imperial City have immediately started to court the Imperial princess, whose hand in marriage would be a prize beyond price in Rokugan. -

Exploring Musical Relations Using Association Rule Networks

EXPLORING MUSICAL RELATIONS USING ASSOCIATION RULE NETWORKS Renan de Padua1;2 Veronicaˆ Oliveira de Carvalho3 Solange de Oliveira Rezende1 Diego Furtado Silva4 1 Instituto de Cienciasˆ Matematicas´ e de Computac¸ao˜ – Universidade de Sao˜ Paulo, Sao˜ Carlos, Brazil 2 Data Science Team, Itau-Unibanco,´ Sao˜ Paulo, Brazil* 3 Instituto de Geocienciasˆ e Cienciasˆ Exatas – Universidade Estadual Paulista, Rio Claro, Brazil 4 Departamento de Computac¸ao˜ – Universidade Federal de Sao˜ Carlos, Sao˜ Carlos, Brazil [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT features from subsequences to obtain a more robust set of features [2, 8]. Moreover, Silva et al. [12] showed how as- Music information retrieval (MIR) has been gaining in- sessing distances between subsequences can be used as a creasing attention in both industry and academia. While subroutine for different MIR tasks, from cover recognition many algorithms for MIR rely on assessing feature sub- to visualization. sequences, the user normally has no resources to interpret In this work, we propose the use of a novel category the significance of these patterns. Interpreting the relations of association rules networks to support understanding the between these temporal patterns and some aspects of the relations between sequential patterns and labels which de- assessed songs can help understanding not only some algo- scribe our data. The exploration of these association rules rithms’ outcomes but the kind of patterns which better de- may provide insights on what kind of pattern defines one fines a set of similarly labeled recordings. In this work, we label, which may have implications on musicology or other present a novel method to assess these relations, construct- MIR tasks. -

The Reading Agency Is a National Charity That Tackles Life's Big Challenges Through the Proven Power of Reading

The Reading Agency is a national charity that tackles life's big challenges through the proven power of reading. We work closely with partners to develop and deliver programmes for people of all ages and backgrounds. The Reading Agency is funded by Arts Council England. https://readingagency.org.uk/ October is Black History Month so is the perfect time to celebrate some brilliant books for children and young people created by black authors and illustrators. Our list of 65 titles includes fiction, non- fiction, poetry and graphic novels for all children, young people and adults to enjoy reading. Find out more about Black History Month here: https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/. Contents • Page 1 – Picture books • Page 7 – Middle grade books • Page 14 – Young people books • Page 23 – Finding your next read • Page 24 – Overview of the full list of 65 brilliant books for children and young people by black authors and illustrators Brilliant books for children and young people by black authors and illustrators Picture books A Story About Afiya by James Berry and Anna Cunha 978-1911373339, Lantana Publishing Some people have dresses for every occasion but Afiya needs only one. Her dress records the memories of her childhood, from roses in bloom to pigeons in flight, from tigers at the zoo to October leaves falling. A joyful celebration of a young girl’s childhood, written by the late Coretta Scott King Book Award-winning Jamaican poet James Berry. Astro Girl by Ken Wilson-Max 978-1910959213, Otter-Barry Books Astrid has always loved the stars and space. -

Morpheus F ALL 2014

BUSINESS NAME V OLUME 1, I SSUE 1 Morpheus F ALL 2014 Much Ado About Nothing: A Modern Take Susan McConnell, This play focuses on Hannah Talbee, and two main relationships, Men: Michelle Motil proudly and the one we've cho- present… sen to focus on is that Setting: Williard of Beatrice and Ben- Suite Much Ado About edick, the bickering Something duo who are so self- Women: A Modern Playwrite aware, they deem Setting: France themselves above con- Hall bathroom Introduction: vention-- and each oth- er. Don Pedro= We here at Morpheus So, here are two Pedro have decided to bring separate, yet very simi- Hero= Hero Shakespeare to cam- lar scenes involving Leonato= Leo pus! Beatrice, Benedick, Margaret= Margie MORPHEUS CON- TEST WINNERS What you are about and their friends. In Claudio= Clay Ursu- to read are two scenes these scenes, the re- la= Sula Essay Category from one of Shake- spective friends of the Benedick= Ben Be- "Analysis of Sexist Mar- speare's comedies couple are ensuring atrice= Beatrice keting in Photos" and "The Much Ado About Noth- that they become just Chrysanthemums." By ing. that: a couple. (Story cont. pg. 3) Susan McConnell and Alexis McClinans respec- tively. Pages 9 and 11 Poetry Category Hannukah Cheer 1st place: Rachel Peters, "Fade" Page 12 2nd place: Alexandria Wick, "Always Will Love Light the first of eight lord, You" Page 6 tonight— every dusk one candle 3rd place: Susan McConnell, "Gay Equality, the farthest candle to the more Everywhere!" Page 6 right. And an eight-day feast Fiction Category proclaimed— Light the first and sec- Till all eight burn bright The Festival of Lights— 1. -

No More Rules Graphic Design and Postmodernism by Rick Poynor

No More Rules Graphic Design and Postmodernism by Rick Poynor Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Unlimited ebooks*. Accessible on all your screens. Ebook No More Rules Graphic Design and Postmodernism available for review only, if you need complete book "No More Rules Graphic Design and Postmodernism" please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >>> *Please Note: We cannot guarantee that every file is in the library. You can choose FREE Trial service and download "No More Rules Graphic Design and Postmodernism" ebook for free. Book Details: Review: I love it!!! It is a beautiful book!!! I start reading it, and it gives very clear idea on post modernism. I hope I will get lots of insights from this pretty book. Keep working on it!!!... Original title: No More Rules: Graphic Design and Postmodernism Paperback: 192 pages Publisher: Yale University Press; 50333rd edition (October 1, 2003) Language: English ISBN-10: 0300100345 ISBN-13: 978-0300100341 Product Dimensions:8.5 x 0.7 x 11.1 inches File Format: pdf File Size: 15264 kB Ebook File Tags: Description: The past twenty years have seen profound changes in the field of graphic communication. As the computer has become a ubiquitous tool, there has been an explosion of creativity in graphic design; designers and typographers have jettisoned existing rules and forged experimental new approaches. No More Rules is the first critical survey to offer a complete... No More Rules Graphic Design and Postmodernism PDF Arts and Photography ebooks - No More Rules Graphic Design and Postmodernism rules design graphic and postmodernism more read online postmodernism no and design rules book design rules postmodernism pdf design more and graphic rules postmodernism no pdf download free No More Rules Graphic Design and Postmodernism More Postmodernism Design and Graphic No Rules Ella can only guess. -

Legacies of the US Occupation of Japan: Appraisals After Sixty Years

Legacies of the U.S. Occupation of Japan Legacies of the U.S. Occupation of Japan: Appraisals after Sixty Years Edited by Rosa Caroli and Duccio Basosi Legacies of the U.S. Occupation of Japan: Appraisals after Sixty Years Edited by Rosa Caroli and Duccio Basosi This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Rosa Caroli, Duccio Basosi and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7197-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7197-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................................................... vii Glenn Hook Introduction ................................................................................................ ix The editors Editors’ Note .......................................................................................... xxiv Part I: Politics, Society and Culture Japan and the US: An Odd Couple .............................................................. 2 Ronald Dore, London School of Economics Reconciling Asianism with Bilateralism: Japan and the East Asia Summit ..................................................................................................... -

Poetry: the Language of Love in Tale of Genji

Poetry: The Language of Love in Tale of Genji YANPING WANG This article examines the poetic love presented by waka poetry in the Tale of Genji. Waka poetry comprises the thematic frame of Tale of Genji. It is the language of love. Through observation of metaphors in the waka poems in this article, we can grasp the essence of the poetics of love in the Genji. Unlike the colors of any heroes’ and heroines’ love in other literary works, Genji’s love is poetic multi-color, which makes him a mythopoetic romantic hero in Japanese culture. Love in Heian aristocracy is sketched as consisting of an elaborate code of courtship which is very strict in its rules of communion by poetry. Love is a romantic adventure without compromise and bondage of morality. The love adventure of Genji and other heroes involves not only aesthetic Bildung and political struggle but also poetic production and metaphorical transformation. The acceptance of the lover’s poetic courtship creates an artistic and romantic air to the relations between men and women. Love and desire are accompanied by a ritual of elegance, grace and a refined cult of poetic beauty. There are 795 poems (waka) in the Genji. They are used in the world of the Genji as a medium of interpersonal communication, as a means to express individual emotions and feelings, as an artistic narrative to poeticize the romance and as an artistic form to explore the internal life of the characters.1 Nearly 80 percent (624) of these 795 poems are exchanges (zotoka), 107 are solo recitals and 64 are occasional poems.2 -

Style Is Not a Four Letter Word Mr. Keedy 2004

LC5 03.qxd 12/1/06 12:29 PM Page 94 94 looking closer 5 style is not a four letter word Mr. Keedy Today, the emphasis on style over content in much of what is alleged to be graphic design and communication is, at best, puzzling. —Paul Rand,Design,Form and Chaos The work arises as a methodological consequence—not from streaming projects through some stylistic posture. —Bruce Mau,Life Style Looking at other magazines from all fields it seems that “serious” content-driven publications don’t care how they look, whilst “superficial” content-free ones resort to visual pyrotechnics. —Editors,DotDotDot,issue no.1 Good design means as little design as possible. —Dieter Rams, Omit the Unimportant Style ϭ Fart —Stefan Sagmeister here has been a long and continuing feud in design between style and content, form and function, and even pleasure and utility, to which Charles Eames answered, “Who would say thatT pleasure is not useful?”1 Maybe we should call atruce,since it doesn’t seem like anyone is winning.Animosity towards style is pretty much a given in the design rhetoric of the twentieth century. But where did this antag- onistic relationship between design and style come from? And more importantly, what has it done for us? At the end of the stylistic excess and confusion of the Victorian era, the architect Adolf Loos led the way to a simpler, progressive, and more profitable future. In 1908 he proclaimed, “I have discovered the following truth and presented it to the world: cultural evolution is synonymous with the removal of ornament from articles in daily use.”2 In his polemical and now famous essay “Ornament and Crime,”Adolf Loos established what would be the prevalent attitude towards orna- ment, pattern, decoration, and style in the twentieth century.