Castles Made of Sand Lorraine Wild

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Books on Art & Culture

S11_cover_OUT.qxp:cat_s05_cover1 12/2/10 3:13 PM Page 1 Presorted | Bound Printed DISTRIBUTEDARTPUBLISHERS,INC Matter U.S. Postage PAID Madison, WI Permit No. 2223 DISTRIBUTEDARTPUBLISHERS . SPRING 2011 NEW BOOKS ON SPRING 2011 BOOKS ON ART AND CULTURE ART & CULTURE ISBN 978-1-935202-48-6 $3.50 DISTRIBUTED ART PUBLISHERS, INC. 155 SIXTH AVENUE 2ND FLOOR NEW YORK NY 10013 WWW.ARTBOOK.COM GENERAL INTEREST GeneralInterest 4 SPRING HIGHLIGHTS ArtHistory 64 Art 76 BookDesign 88 Photography 90 Writings&GroupExhibitions 102 Architecture&Design 110 Journals 118 MORE NEW BOOKS ON ART & CULTURE Special&LimitedEditions 124 Art 125 GroupExhibitions 147 Photography 157 Catalogue Editor Thomas Evans Architecture&Design 169 Art Direction Stacy Wakefield Forte Image Production Nicole Lee BacklistHighlights 175 Data Production Index 179 Alexa Forosty Copy Writing Sara Marcus Cameron Shaw Eleanor Strehl Printing Royle Printing Front cover image: Mark Morrisroe,“Fascination (Jonathan),” c. 1983. C-print, negative sandwich, 40.6 x 50.8 cm. F.C. Gundlach Foundation. © The Estate of Mark Morrisroe (Ringier Collection) at Fotomuseum Winterthur. From Mark Morrisroe, published by JRP|Ringier. See Page 6. Back cover image: Rodney Graham,“Weathervane (West),” 2007. From Rodney Graham: British Weathervanes, published by Christine Burgin/Donald Young. See page 87. Takashi Murakami,“Flower Matango” (2001–2006), in the Galerie des Glaces at Versailles. See Murakami Versailles, published by Editions Xavier Barral, p. 16. GENERAL INTEREST 4 | D.A.P. | T:800.338.2665 F:800.478.3128 GENERAL INTEREST Drawn from the collection of the Library of Congress, this beautifully produced book is a celebration of the history of the photographic album, from the turn of last century to the present day. -

Works S11-1.Pub

Fall 2010-Spring 2011 The Official Arts Publication of Sauk Valley Community College TheThe WorksWorks honorable mention in student visual art contest (above): Carlow, Ireland by William Brown Fiction Poetry Visual Arts The Anne Horton Writing Award 2011 Film Review Contest The Works Editorial Staff . Sara Beets Elizabeth Conderman Cody Froeter Tessa Ginn Tracy Hand Steven Hoyle James Hyde Jamie Lybarger Lauren Walter David Waters Faculty Advisor . Tom Irish * * * * * Special thanks to SVCC’s Foundation, Student Government Association, and English Department 2 Table of Contents . POETRY: First Place: Human Cannibalization: A Study, by Lauren Walter . 4 Honorable Mention: At the End of the Wind, by Phil Arellano . 6 Doesn’t Feel Right, by Sara Beets . 7 Goodnight, by Hayleigh Covella . 8 Two Caves, by Corey Coomes . .10 Doesn’t Feel Right, by Tessa Ginn . 11 Speed Kills, by Corey Coomes . 12 Something About Bravery, by Lauren Walter . .13 In My Place, by Jamie Lybarger . 14 Oh Sweetie, Oh Please, by Hayleigh Covella . 16 Mortal, by Sara Beets . 17 Hot Tears of Love, by Len Michaels . 18 Unimpressed, by Hayleigh Covella . 19 Planet Mars-Population: Failure, by Sara Beets . 20 Seventh Sin: A Collection of Poetry, by Sara Beets , Tessa Ginn, and Lauren Walter . 22 FICTION: First Place: Emperor Onion, by Elizabeth Conderman . 32 Honorable Mention: Buried, by Lauren Walter . 35 The Legend of the Pipperwhill, by Brooke Ehlert. 38 MICHAEL JUSTIN, by Rebekah Megill . 40 Just Animals, by Nick Sobottka . 42 The FINAL CHAPTER of NICK CARTER: The Price, by Jason Hedrick . 44 Pleasant Dreams, by Len Michaels . 47 A Very Short Story About Fruit Snacks, by Tom Irish . -

Interaction Between Record Matching and Data Repairing

Interaction between Record Matching and Data Repairing Wenfei Fan1;2 Jianzhong Li2 Shuai Ma3 Nan Tang1 Wenyuan Yu1 1University of Edinburgh 2Harbin Institute of Technology 3Beihang University fwenfei@inf., ntang@inf., [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract cost: it costs us businesses 600 billion dollars each year [16]. Central to a data cleaning system are record matching and With this comes the need for data cleaning systems. As data repairing. Matching aims to identify tuples that re- an example, data cleaning tools deliver \an overall business fer to the same real-world object, and repairing is to make a value of more than 600 million GBP" each year at BT [31]. In database consistent by fixing errors in the data by using con- light of this, the market for data cleaning systems is grow- straints. These are treated as separate processes in current ing at 17% annually, which substantially outpaces the 7% data cleaning systems, based on heuristic solutions. This pa- average of other IT segments [22]. per studies a new problem, namely, the interaction between There are two central issues about data cleaning: ◦ record matching and data repairing. We show that repair- Recording matching is to identify tuples that refer to ing can effectively help us identify matches, and vice versa. the same real-world entity [17, 26]. ◦ To capture the interaction, we propose a uniform frame- Data repairing is to find another database (a candidate work that seamlessly unifies repairing and matching oper- repair) that is consistent and minimally differs from ations, to clean a database based on integrity constraints, the original data, by fixing errors in the data [4, 21]. -

Book Proposal 3

Rock and Roll has Tender Moments too... ! Photographs by Chalkie Davies 1973-1988 ! For as long as I can remember people have suggested that I write a book, citing both my exploits in Rock and Roll from 1973-1988 and my story telling abilities. After all, with my position as staff photographer on the NME and later The Face and Arena, I collected pop stars like others collected stamps, I was not happy until I had photographed everyone who interested me. However, given that the access I had to my friends and clients was often unlimited and 24/7 I did not feel it was fair to them that I should write it all down. I refused all offers. Then in 2010 I was approached by the National Museum of Wales, they wanted to put on a retrospective of my work, this gave me a special opportunity. In 1988 I gave up Rock and Roll, I no longer enjoyed the music and, quite simply, too many of my friends had died, I feared I might be next. So I put all of my negatives into storage at a friends Studio and decided that maybe 25 years later the images you see here might be of some cultural significance, that they might be seen as more than just pictures of Rock Stars, Pop Bands and Punks. That they even might be worthy of a Museum. So when the Museum approached me three years ago with the idea of a large six month Retrospective in 2015 I agreed, and thought of doing the usual thing and making a Catalogue. -

Postmodernism

Black POSTMODERNISM STYLE AND SUBVERSION, 1970–1990 TJ254-3-2011 IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm 175L 130 Stora Enso M/A Magenta(V) 130 Stora Enso M/A 175L IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm TJ254-3-2011 1 Black Black POSTMODERNISM STYLE AND SUBVERSION, 1970–1990 TJ254-3-2011 IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm 175L 130 Stora Enso M/A Magenta(V) 130 Stora Enso M/A 175L IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm TJ254-3-2011 Edited by Glenn Adamson and Jane Pavitt V&A Publishing TJ254-3-2011 IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm 175L 130 Stora Enso M/A Magenta(V) 130 Stora Enso M/A 175L IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm TJ254-3-2011 2 3 Black Black Exhibition supporters Published to accompany the exhibition Postmodernism: Style and Subversion, 1970 –1990 Founded in 1976, the Friends of the V&A encourage, foster, at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London assist and promote the charitable work and activities of 24 September 2011 – 15 January 2012 the Victoria and Albert Museum. Our constantly growing membership now numbers 27,000, and we are delighted that the success of the Friends has enabled us to support First published by V&A Publishing, 2011 Postmodernism: Style and Subversion, 1970–1990. Victoria and Albert Museum South Kensington Lady Vaizey of Greenwich CBE London SW7 2RL Chairman of the Friends of the V&A www.vandabooks.com Distributed in North America by Harry N. Abrams Inc., New York The exhibition is also supported by © The Board of Trustees of the Victoria and Albert Museum, 2011 The moral right of the authors has been asserted. -

And Acquaintances Recall Their Dealings with The

REASONS TO BE CHEERFUL: THE LIFE AND WORK OF BARNEY BUBBLES by paul gorman Book reviewed by Andy Martin 2 4 1 In 1974, forsaking the wisdom with finesse and melon twisting and acquaintances recall their early ‘impersonators’ (some of of my art college tutors in favour packaging concepts. And for me, dealings with the man, sometimes whom ‘fess up’ in the book) went of long afternoons in the library, there lies Barney Bubbles’ secret, with great poignancy, such as ex- on to define the subsequent I stumbled upon the works of namely his ability to look Stiff Records’ staffer Susan Spiro cultural period, and all of them Eduardo Paolozzi, Constructivism, backwards and forwards at the recalling Bubbles’ ability (me included) owe this man a Krazy Kat, and a strange volume same time, whilst always to see the beauty in everyday huge debt. by Charles Jenks, Adhocism – managing to arrive at The Very objects. There is ample evidence This book is a treasure trove The Case for Improvisation. Point of Now-ness. also that alongside his own for image-makers across all Within a couple of years I noticed As it progresses, the book image-making he was no slouch media, and a reminder that the a similar admix of ideas gives us epoch-defining glimpses when it came to art direction, graphic bombs Barney Bubbles appearing in the work of one of a shuddering cultural drawing on the talents of some dropped are still reverberating. man, but due to his reluctance landscape, clouds of patchouli of the most forward thinking In the words of the late great to credit his artworks, time would oil fade and a new world forms, photographers of the era, Brian Ian Dury: there ain’t half been have to pass before the author’s accompanied by the distinct whiff Griffin and Chris Gabrin amongst some clever bastards. -

Better Is Better Than More: Complexity, Economic Progress, and Qualitative Growth

Better is Better Than More Complexity, Economic Progress, and Qualitative Growth by Michael Benedikt and Michael Oden Center for Sustainable Development Working Paper Series - 2011(01) csd Center for Sustainable Development The Center for Sustainable Development Better is Better than More: Complexity, Economic Working Paper Series 2011 (01) Progress, and Qualitative Growth Better is Better than More: Complexity, Economic Progress, and Qualitative Growth Michael Benedikt Hal Box Chair in Urbanism Michael Oden Professor of Community & Regional Planning Table of Contents The University of Texas at Austin 1. Introduction, and an overview of the argument 2 © Michael Benedikt and Michael Oden 2. Economic growth, economic development, and economic progress 6 Published by the Center for Sustainable Development The University of Texas at Austin 3. Complexity 10 School of Architecture 1 University Station B7500 Austin, TX 78712 4. The pursuit of equity as a generator of complexity 21 All rights reserved. Neither the whole nor any part of this paper may be reprinted or reproduced or quoted 5. The pursuit of quality as a generator of complexity 26 in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other Richness of functionality 31 means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information Reliability/durability 32 storage or retrieval system, without accompanying full Attention to detail 33 bibliographic listing and reference to its title, authors, Beauty or “style” 33 publishers, and date, place and medium of publication or access. Generosity 36 Simplicity 37 Ethicality 40 The cost of quality 43 6. Quality and equity together 48 The token economy 50 7. -

The Working Practices of Barney Bubbles | I-D Online 28/09/2010 22:59

PROCESS: The Working Practices of Barney Bubbles | i-D Online 28/09/2010 22:59 Home » i-Spy » PROCESS: The Working Practices of Barney Bubbles search - Published by i-D 11:49 GMT 22/09/10 More + Cited as a major influence to contemporary practitioners including Peter Saville, Malcolm Garrett and Neville Brody, Barney Bubbles was a radical graphic artist. Coinciding with the London Design Festival, last night the CHELSEA Space celebrated its latest exhibition showcasing the working processes of the late master designer. Born Colin Fulcher (he loved a pseudonym and stuck with Bubbles in 67), the enigmatic designer worked across the disciplines of graphic design, painting and music video direction, working with artists including Ian Drury, Elvis Costello, Billy Bragg and Iggy Pop. Referred to as "the missing link between Pop and Culture" by Peter Saville, Bubbles was most renowned for his work with the British independent music scene during the 70s and early 80s. Fellow designer Julian Balme who created sleeves for Madness, Clash and Adam and The Ants and would often visit Bubbles at his studio, told i-D Online, "Bubbles taught me more than any other university lecturer". More + Curated by Paul Gorman, PROCESS includes an array of work never previously shown, most of it borrowed from private collections. The displays are fascinating and represent the varying stages of Bubbles' creative life, including student notebooks, reference materials, his CV, original artwork, books, magazines, paintings, photography, record sleeves, T-shirts, posters, advertisements, badges and stickers and videos directed by Bubbles. Together, the exhibition clearly demonstrates the designer's signature style. -

The Nerevarine Chronicles

The Nerevarine Chronicles Peace and Prosperity The kingdom of Avalon had existed for nearly a millennium, enjoying peace and prosperity for many of those centuries. In the ebb and flow of time, the races of Avalon united when necessary to converge on a common foe. For the most part, however the dwarves and elves tended to themselves and let the humans, with their shorter life spans, micro-manage the kingdom. As was the custom among humans at the time, people were addressed first by their surname and then their given name. The family name had taken precedence some generations prior, when the Great Houses of Northwind took prominence. Each ruling family was designated as House so-and-so. It did not take long for the custom to trickle out to the human rulers in Dai-Rynn and Dormack. The Great Houses were sometimes referenced by the family crest. House Dagoth, who were worshippers of Pelor, sported a rising sun above a sword, and was commonly called the Sun-and-Sword. House Indoril was called the Moon-and-Star, after their crest, which resembled a tiny slice of the night sky. House Indoril followed Heironeous and the origin of their crest remains a mystery. After the events surrounding the Nerevarine Prophecies, however, this all but ended. Family names were held with honor and pride, but took no more importance over the individual than they had prior. The Great Houses stopped referring to each other as such and that era was left in the wake of these unfortunate events to fade only into the annals of history. -

LL-L5R Rules.Pdf

A few months ago, the Empress of Rokugan’s third child, Iweko Miaka, came of age. This instantly made her the most eligible maiden in the Empire, and prominent samurai from every clan and faction have set out to court her. Of course, in Rokugan marriage is a matter of duty and politics far more often than love, but the personal affection of a potential spouse can be a very effective tool in marriage negotiations. And when that potential spouse is an Imperial princess, her affection can be more influential than any number of political favors. 2 Of course, winning a princess’ heart is hardly an easy task in the tightly- monitored world of the Imperial Palace. The preferred tool of courtly romance in Rokugan is the letter, and every palace’s corridors are filled with the soft steps of servants carrying letters back and forth. But such letters can be intercepted by rivals or turned away by hostile guards. For a samurai to succeed in his suit, he will have to find ways of getting his own letters into Miaka’s hands – while blocking the similar efforts of rival suitors. 3 Object In the wake of many recent tragic events, Empress Iweko I has sought to bring a note of joy back to the Imperial City, Toshi Ranbo, by announcing the gempukku (coming- of-age) of her youngest child and only daughter, Iweko Miaka. Prominent samurai throughout the Imperial City have immediately started to court the Imperial princess, whose hand in marriage would be a prize beyond price in Rokugan. -

DOG MEASURE 070513Web

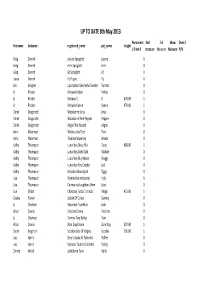

UP TO DATE 8th May 2013 Permanent 2nd 3rd Show Over 2 firstname lastname registered_name pet_name height 1 if not 0 measure Measure Measure Y/N Greg Derrett Jaycee Sproglett Jaycee 0 Greg Derrett Fern Sproglett Fern 0 Greg Derrett Gt Sproglett Gt 0 Laura Derrett FlyPuppy Fly 0 Jim Gregson Lipsmackin Gesviesha Twister Twister 0 Jo Rhodes Moravia Kelbie Kelbie 0 Jo Rhodes Moravia Ci Ci 470.00 1 Jo Rhodes Moravia Kaesie Kaesie 470.00 1 Derek Dragonetti Woodsorrel Jinja Jinja 0 Derek Dragonetti Woodsorrel Red Pepper Pepper 0 Derek Dragonetti Aligan The Wizard Aligan 0 Anne Alderman Wotta Lotta Tosh Tosh 0 Anne Alderman Trueline Waveney Breeze 0 Kathy Thompson Lunarlites Dizzy Mix Dizzy 488.00 1 Kathy Thompson Lunarlites Dark Gold Maddie 0 Kathy Thompson Lunarlites Blue Moon Braggi 0 Kathy Thompson Lunarlites Fire Cracker Jed 0 Kathy Thompson Myndoc Moon Spirit Tiggy 0 Lisa Thompson Wynmallen Indiscreet Indy 0 Lisa Thompson Caninarosa Laughters Here Jake 0 Sue Elliott Chakotay Turbo Tornado Megan 475.00 1 Cayley Turner Splash Of Colour Sammy 0 Jo Chalmers Raeannes True Blue Josh 0 Alison Cronin Fletcher Cronin Fletcher 0 Jo Chalmers Tommy Two Bellies Tom 0 Alison Cronin Zoro Dog Cronin Zoro Dog 507.00 1 Sarah Beighton Scoobie Doo Of Valgray Scoobie 506.00 1 Lois Harris Zero's Aysha At Tolnedra Toffee 0 Lois Harris Starazaz Todd At Tolnedra Toddy 0 Denise Welsh Jadedoren Paris Harlie 0 Cathy Brown Blue Dippy Do Lally Dippy 0 Cathy Brown Dippity Doodah Scooby 0 Soraya Porter Hartsfern In Earnest Ernest 336.00 1 Maureen Goodchild Crystalgorse -

Exploring Musical Relations Using Association Rule Networks

EXPLORING MUSICAL RELATIONS USING ASSOCIATION RULE NETWORKS Renan de Padua1;2 Veronicaˆ Oliveira de Carvalho3 Solange de Oliveira Rezende1 Diego Furtado Silva4 1 Instituto de Cienciasˆ Matematicas´ e de Computac¸ao˜ – Universidade de Sao˜ Paulo, Sao˜ Carlos, Brazil 2 Data Science Team, Itau-Unibanco,´ Sao˜ Paulo, Brazil* 3 Instituto de Geocienciasˆ e Cienciasˆ Exatas – Universidade Estadual Paulista, Rio Claro, Brazil 4 Departamento de Computac¸ao˜ – Universidade Federal de Sao˜ Carlos, Sao˜ Carlos, Brazil [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT features from subsequences to obtain a more robust set of features [2, 8]. Moreover, Silva et al. [12] showed how as- Music information retrieval (MIR) has been gaining in- sessing distances between subsequences can be used as a creasing attention in both industry and academia. While subroutine for different MIR tasks, from cover recognition many algorithms for MIR rely on assessing feature sub- to visualization. sequences, the user normally has no resources to interpret In this work, we propose the use of a novel category the significance of these patterns. Interpreting the relations of association rules networks to support understanding the between these temporal patterns and some aspects of the relations between sequential patterns and labels which de- assessed songs can help understanding not only some algo- scribe our data. The exploration of these association rules rithms’ outcomes but the kind of patterns which better de- may provide insights on what kind of pattern defines one fines a set of similarly labeled recordings. In this work, we label, which may have implications on musicology or other present a novel method to assess these relations, construct- MIR tasks.