U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration National Weather Service National Centers for Environmental Prediction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diving Accident / Incident Report Form

DIVING ACCIDENT / INCIDENT REPORT FORM NOTE: FAU Scientific Divers shall use this form to report diving related accidents, injuries, and incidents including; near-drowning, decompression sickness, gas embolism, lung overexpansion, or injuries that require hospitalization as well as any incidents that compromised diver safety or might result in later hospitalization, therapy, or litigation. FAU Dive Logs for all dives related to the accident / incident must also be submitted with this report. Contact the FAU Dive Safety Officer at 561-297-3129 with questions about whether or not to report an incident. GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE ACCIDENT/ INCIDENT VICTIM DIVER NAME: DATE & TIME OF INCIDENT: DIVE LOCATION: DIVING CERTIFICATION LEVEL: CERTIFICATION DEPTH: Scientific Diver Diver-In-Training Temporary Diver CURRENT MEDICATIONS: CURRENT HEALTH PROBLEMS: If the diver is not anFAU-certified diver, complete this section. FAU-certified divers skip to the next section. AGE: SEX: (M/F) DIVER’S AGENCY OR ORGANIZATION: AGENCY OR ORGANIZATION DSO NAME & TELEPHONE #: # YEARS DIVING: TOTAL # DIVES: # DIVES LAST 6 MONTHS: PREVIOUS DIVE INCIDENTS & DATES: DESCRIPTION OF THE ACCIDENT / INCIDENT: Please describe accident / incident in detail. Include ANY factor which you believe may have contributed to, or minimized the accident / incident. If more than one accident / incident occurred please fill out a separate form. Use extra paper if necessary. What could have been done to prevent this accident / incident? Did the accident / incident cause harm: Diver’s qualification: (may circle >1) Yes No Not known Diving student …… DS Open water ……...OW Advanced diver…….AD Divemaster ……...DM Specify : Dive instructor ….. DI Untrained …… .. UT Professional ……... PD Technical diver…...TD Not known ……. -

Iquod International Quality-Controlled Ocean Database 2Nd Annual Workshop Report

IQuOD International Quality-Controlled Ocean Database 2nd Annual Workshop Report June 4-6, 2014 NOAA, Silver Spring, USA. http://www.iquod.org http://www.iquod.org 2nd IQuOD Workshop Report. June 4-6, 2014 1 Editor Rebecca Cowley, CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research, Australia Bibliographic Citation IQuOD (International Quality-controlled Ocean Database) 2nd Annual Workshop Report, July, 2014. Sponsorship Sponsorship for tea/coffee breaks was kindly provided by UCAR. 2nd IQuOD Workshop Report. June 4-6, 2014 2 Table of Contents Workshop Summary ...................................................................................................... 5 1. Setting the scene – current project structure, workplan and progress made in the last year .............................................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Project aims and structure (Catia Domingues) .................................................................... 6 1.2 Recap on goals for Auto QC, Manual QC, Data aggregation and Data assembly groups (Ann Thresher) ....................................................................................................................... 7 1.3 The scientific implementation plan and plans for CLIVAR endorsement (Matt Palmer) ......... 8 1.4 Session 1 discussion .......................................................................................................... 9 2. Auto QC group benchmarking results ...................................................................... -

Chapter 3 Patron Surveillance

Chapter 3 Patron Surveillance A lifeguard’s primary responsibility is to en- sure patron safety and protect lives. A pri- mary tool to accomplish this function is pa- tron surveillance—keeping a close watch over the people in the facility. Lifeguards will spend most of their time on patron sur- veillance. To do this effectively, they must be alert and attentive at all times, supervis- ing patrons continuously. 28 Lifeguarding EFFECTIVE SURVEILLANCE Distressed Swimmer For a variety of reasons, such as exhaustion, cramp or With effective surveillance, lifeguards can recognize be- sudden illness, a swimmer can become distressed. A dis- haviors or situations that might lead to life-threatening tressed swimmer makes little or no forward progress and emergencies, such as drownings or injuries to the head, may be unable to reach safety without a lifeguard’s assis- neck or back, and then act to modify the behavior or tance. control the situation. Effective surveillance has several Distressed swimmers can be recognized by the way elements: they try to support themselves in the water. They might ● Victim recognition float or use swimming skills, such as sculling or treading ● Effective scanning water. If a safety line or other floating object is nearby, a ● Lifeguard stations distressed swimmer may grab and cling to it for support. ● Area of responsibility Depending on the method used for support, the dis- tressed swimmer’s body might be horizontal, vertical or The previous chapter focused on eliminating haz- diagonal (Fig. 3-2). ardous situations. This chapter concentrates on recogniz- The distressed swimmer usually has enough control of ing patrons who either need, or might soon need, assis- the arms and legs to keep his or her face out of the water tance. -

Ways of Being in Trauma-Based Society

Ways of Being in Trauma-Based Society: Discovering the Politics and Moral Culture of the Trauma Industry Through Hermeneutic Interpretation of Evidence-Supported PTSD Treatment Manuals A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Antioch University Seattle Seattle, WA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Doctor of Psychology By Sarah Peregrine Lord May 2014 Ways of Being in Trauma-Based Society: Discovering the Politics and Moral Culture of the Trauma Industry Through Hermeneutic Interpretation of Evidence-Supported PTSD Treatment Manuals This dissertation, by Sarah Peregrine Lord, has been approved by the Committee Members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of the Antioch University Seattle at Seattle, WA in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: ________________________ Philip Cushman, Ph.D. ________________________ Jennifer Tolleson, Ph.D. ________________________ Lynne Layton, Ph.D., Ph.D. ________________________ Date ii © Copyright by Sarah Peregrine Lord, 2014 All Rights Reserved iii Abstract Ways of Being in Trauma-Based Society: Discovering the Politics and Moral Culture of the Trauma Industry Through Hermeneutic Interpretation of Evidence-Supported PTSD Treatment Manuals Sarah Peregrine Lord Antioch University Seattle Seattle, WA One-hundred percent of evidence-supported psychotherapy treatments for trauma related disorders involve the therapist learning from and retaining fidelity to a treatment manual. Through a hermeneutic qualitative textual interpretation of three widely utilized evidence-supported trauma treatment manuals, I identified themes that suggested a particular constitution of the contemporary way of being—a traumatized self—and how this traumatized self comes to light through psychotherapeutic practice as described by the manuals. -

SCUBA DRILLS Snorkeling Gear Prep, Entry, Snorkel Clear, Kicks Gear Prep: Mask (Ant Fogged) –Fins, Gloves, Boots, Ready by Entry Point Access

(616) 364-5991 SCUBA DRILLS WWW.MOBYSDIVE.COM Snorkeling Gear Prep, Entry, Snorkel clear, Kicks Gear prep: Mask (ant fogged) –fins, gloves, boots, ready by entry point access. (it is crucial that the mask-fins-boots are properly designed and fitted before the aquatic session to prevent delays in training due to gear malfunction ) Equipment nicely assembled by entry point for easy donning and water access ENABLED EQUIPMENT NICELY ASSEMBLED – BUDDY CHECK – LOGBOOK CHECK – ENTRY – DRILL REVIEW Equipment Nicely Assembled: (Each Diver needs to develop the practice of properly assembling their scuba gear by themselves) Full tank secured until ready for gear assembly. Tank upright, BCD tank band straps are loosened as to allow easy placement of strap around the tank. NOTE: Hard pack BCD’s usually have ONE tank band, Soft pack BCD’s usually have TWO tank bands. Most bands have a buckle / cam strap and need to be weaved a particular way to stay secured. Ensure the BCD’s placement on the tank so the tank valve is level with where the diver’s neck will be and that the front part of the valve (where the air is released) is facing the back of the diver. Secure the strap or straps so they are tight enough to pick up the BCD and tank and not slip while shaking. Regulator placement: The First stage (dust cap removed) is placed over the tank valve so the intake of the 1st stage covers the o-ring on the tank valve, (o-ring should be in place – if not, lack of seal will cause air leak). -

Buddy Board System for Swimming Areas

Children’s Camps Buddy/Board Systems Contents Buddy/Board System Components Swimming assessments Swimming areas Buddy system Board system or equivalent accountability system Public Health Hazards Safety Plan Swimming Assessments • Assessment of swimming abilities for each camper (also recommended for staff) – Determined by a progressive swim instructor (PSI) – Conducted annually and as appropriate – Campers considered non-swimmers until determined otherwise by PSI • Minimum of two bather classifications: – Non-swimmer and swimmer • See DOH Fact Sheet titled Progressive Swimming Instructor for NYS Children's Camps for approved PSI certifications • Annual assessments are needed - camper’s swimming abilities may change from year to year due to injures and/or changes in fitness or physical abilities. • Reassessment needed to advance to the next level. • Assessment should be appropriate for the type of facility (i.e., pool, lake). Swimming Assessments • Assessment criteria is not specified in Subpart 7-2 • ARC Camp Aquatic Director Training Module suggested criteria for “Swimmers”: – Ability to swim 50 yards using a minimum of two strokes – Change direction while swimming include prone & supine positions – Ability to follow directions of lifeguards No standard/code required assessment criteria. Based on their training, a PSI uses swimming criteria for instruction, which does not necessarily correspond to “Swimmer” and “Non- swimmer” categories. Assessment criteria and categories must be specified in the safety plan and identify which level is equivalent to a non-swimmer. The ARC Camp Aquatic Training Module is no longer available. It was developed in 2001 in a collaborative effort between the American Red Cross (ARC), the NYSDOH and the camping industry. -

Diving Safe Practices Manual

Diving Safe Practices Manual Underwater Inspection Program U.S. Department of the Interior February 2021 Mission Statements The Department of the Interior conserves and manages the Nation’s natural resources and cultural heritage for the benefit and enjoyment of the American people, provides scientific and other information about natural resources and natural hazards to address societal challenges and create opportunities for the American people, and honors the Nation’s trust responsibilities or special commitments to American Indians, Alaska Natives, and affiliated island communities to help them prosper. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Diving Safe Practices Manual Underwater Inspection Program Prepared by R. L. Harris (September 2006) Regional Dive Team Leader and Chair Reclamation Diving Safety Advisory Board Revised by Reclamation Diving Safety Advisory Board (February 2021) Diving Safe Practices Manual Contents Page Contents .................................................................................................................................. iii 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Use of this Manual ............................................................................................. 1 1.2 Diving Safety ..................................................................................................... -

Data Buoy Cooperation Panel

Intergovernmental Oceanographic World Commission of UNESCO Meteorological Organization DATA BUOY COOPERATION PANEL SEA SURFACE SALINITY QUALITY CONTROL PROCESSES FOR POTENTIAL USE ON DATA BUOY OBSERVATIONS DBCP Technical Document No. 42 – 2011 – [page left intentionally blank] Intergovernmental Oceanographic World Commission of UNESCO Meteorological Organization DATA BUOY COOPERATION PANEL SEA SURFACE SALINITY QUALITY CONTROL PROCESSES FOR POTENTIAL USE ON DATA BUOY OBSERVATIONS DBCP Technical Document No. 42 Version 1.3 2011 DBCP TD No. 42, p. 4 CONTENTS 1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................ 7 2 AIM .................................................................................................................................. 7 3 OTHER RELATED DOCUMENTS ...................................................................................... 7 4 INPUTS TO THIS DOCUMENT........................................................................................... 8 5 REQUIREMENTS FOR SSS MEASUREMENT (ACCURACY, TIMINGS & RESOLUTIONS) ... 9 6 SUGGESTED QUALITY CONTROL PROCESSES ............................................................ 10 6.1 COMPUTATION OF SALINITY BASED UPON CONDUCTIVITY, TEMPERATURE, AND DEPTH ............. 10 6.2 TROPICAL ATMOSPHERE OCEAN (TAO) ARRAY ............................................................... 11 6.3 NATIONAL DATA BUOY CENTER QUALITY CONTROL OF SALINITY FROM MOORED BUOYS......... 11 6.4 IFREMER/LOCEAN ................................................................................................ -

Diving Skills Diving Skills

Diving Skills Diving Skills Before beginning your open water practical skills training, in a safe, shallow water area you should practice your skills. It is important to have self-confidence in your abilities before beginning open water practical skills training. 11 Diving Skills Donning Snorkel Set [Mask] First, we need to de-fog our mask. Then we need to tie up any loose hair so it doesn’t enter the mask, breaking the seal. After fitting to the De-fog face, pull the straps around the back of the head and adjust the tension. Be Careful of Your Hair [Fin] While your buddy helps support your balance, you hold one fin in which to place your foot while gripping the other empty fin. Once your foot is sufficiently in the pocket, pull tight the strap (of an open heel pocket fin). If you are using the full foot pocket type, carefully fold up the heel. Cooperating With Your Buddy 11 Diving Skills Snorkel Clear Ballast Method To clear your snorkel there is the ballast method and the displacement method. The ballast method involves inhaling a large breath at the surface and blowing strongly into the snorkel. The displacement method involves using the remaining air in the snorkel to blow out while keeping your head up. Either method will allow you to clear your snorkel easily. Displacement Method Fin Work While slightly bending the legs, we slowly and in a large cycle kick with our whole legs. With this method we can gain suitable propulsive power. The dolphin kick can be achieved by joining your legs together and moving them in unison, much as a dolphin does. -

Tune up Your Scuba Skills

To unsubscribe click here SCOTT AND DAVID SCHROEDER ARE NOW PADI ENRICHED AIR SPECIALTY DIVERS. POOL FUN THIS PAST SATURDAY. WHERE WERE YOU? PADI DISCOVER SCUBA SCUBA REVIEW OR JUST COME AND PLAY ANDOVER BRANCH YMCA POOL SATURDAY FEBRUARY 24, 2018 Why PADI Scuba Review? Are you a certified diver, but haven't been in the water lately? Are you looking to refresh your dive skills and knowledge? Are you a PADI Scuba Diver and want to earn your PADI Open Water Diver certification? If you answered yes to any of these questions then PADI Scuba Review is for you. SUNDAY’S FIRST AID GRADUATES What do I need to start? Hold a scuba certification SCUBA SCHOOL Minimum age: 10 years old SCUBA SCHOOL What will I do? FEB 21 WICHITA STATE SCUBA CLASS First, you'll review the safety information you learned during your initial training. Then, you head to the pool to practice some of FEB 23-25 OPEN WATER PART ONE the fundamental scuba skills FEB 24 DISCOVER SCUBA, REFREHSER COURSE, How long will it take? OR JUST COME AND PLAY A couple of hours FEB 25 FIRST AID CLASS What will I need? FEB 28 WICHITA STATE SCUBA CLASS If you don’t have your own gear you will need to rent gear. MAR 2-4 OPEN WATER PART ONE I don’t want a review, but I want to play? MAR 3 DISCOVER SCUBA, REFREHSER COURSE, No problem, Just sign up and come play in the pool for a couple OR JUST COME AND PLAY of hours….we want you diving! MAR 4 FIRST AID CLASS $75.00 for Refresher (includes gear rental and pool fee) MAR 7 WICHITA STATE SCUBA CLASS No Refresher, don’t have gear, but you want to play? Full gear rental $38.00 plus and pool fee. -

Dive Checkout Form

AAUS and UA CHECKOUT DIVE AND TRAINING EVALUATION Certified scientific divers and Divers-In-Training from AAUS organizational members should be able to demonstrate proficiency in the following skills during checkout dives or training evaluation dives with the Dive Safety Officer or designee: ___ Knowledge of AAUS diving standards and regulations ___ Pre-dive planning, briefing, site orientation, and buddy check ___ Use of dive tables and/or dive computer ___ Equipment familiarity ___ Underwater signs and signals ___ Proper buddy contact ___ Monitor cylinder pressure, depth, bottom time ___ Swim skills: ___ Surface dive to 10 ft. without scuba gear ___ Demonstrate watermanship and snorkel skills ___ Surface swim without swim aids (400 yd. <12min) ___ Underwater swim without swim aids (25 yd. without surfacing) ___ Tread water without swim aids (10 min.), or without use of hands (2 min.) ___ Transport another swimmer without swim aids (25yd) ___ Entry and exit (pool, boat, shore) ___ Mask removal and clearing ___ Regulator removal and clearing ___ Surface swim with scuba; alternate between snorkel and regulator (400 yd.) ___ Neutral buoyancy (hover motionless in mid-water) ___ Proper descent and ascent with B.C. ___ Remove and replace weight belt while submerged ___ Remove and replace scuba cylinder while submerged ___ Alternate air source breathing with and without mask (donor/receiver) ___ Buddy breathing with and without mask (donor/receiver) ___ Simulated emergency swimming ascent ___ Compass and underwater navigation ___ Simulated decompression and safety stop ___ Rescue: ___ Self rescue techniques ___ Tows of conscious and unconscious victim ___ Simulated in-water rescue breathing ___ Rescue of submerged non-breathing diver (including equipment removal, simulated rescue breathing, towing, and recovery to boat or shore) ___ Use of emergency oxygen on breathing and non-breathing victim ___ Accident management and evacuation procedures Additional Training (optional) ___ Compressor/ Fill station orientation and usage ___ Small boat handling ___ . -

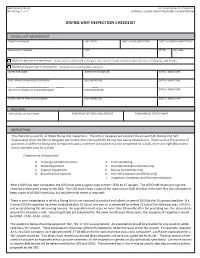

NOAA Form 57-03-03 (08-19) NDP Diving Unit Inspection Checklist.Pdf

NOAA Form 57-03-03 U.S.DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE (08-19) Page 1 of 15 NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION DIVING UNIT INSPECTION CHECKLIST DIVING UNIT INFORMATION DIVING UNIT NAME LINE OFFICE DATE of LAST INSPECTION DATE of CURRENT INSPECTION DIVING UNIT ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE DUSI DIVING UNIT SELF INSPECTION - Conducted annually by UDS or designee, not required if DUSA conducted within previous or following six (6) months. DUSA DIVING UNIT SAFETY ASSESSMENT - Conducted triennially by DSO or designee. INSPECTOR NAME INSPECTOR SIGNATURE DATE of SIGNATURE UNIT DIVING SUPERVISOR (UDS) NAME UDS SIGNATURE DATE of SIGNATURE LINE OFFICE DIVING OFFICER (LODO) NAME LODO SIGNATURE DATE of SIGNATURE DIVING SAFETY OFFCIER (DSO) NAME DSO SIGNATURE DATE of SIGNATURE Ships Only SHIP DIVING OFFICER NAME SHIP DIVING OFFICER E-MAIL ADDRESS COMMANDING OFFICER NAME INSTRUCTIONS This checklist is used for all NOAA Diving Unit Inspections. The UDS or designee will conduct the annual DUSI (Diving Unit Self Assessment) while the DSO or designee will conduct the triennial DUSA (Diving Unit Safety Assessment). There are five (5) sections of questions on different Diving Unit components and a comment area which must be completed for a DUSI, there are eight (8) sections and a comment area for a DUSA. Components of Inspection: A. Training and Administration E. Technical Diving B. Scuba Equipment F. Dive Demonstration (DUSA only) C. Support Equipment G. Rescue Drill (DUSA only) D. Breathing Gas Systems H. Dive Skills Assessment (DUSA only) I. Inspection Comments and Recommendations After a DUSI has been completed, the UDS must send a signed copy to their LODO by 15 January.