The 2006 Asian Games: Self-Affirmation and Soft Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alltime Boys Top 10 Lc, to 15 Sep 2010

Alltime Australian Boys Top 10 long course 11/u to 18 yr - at 15th September 2010 email any errors or omissions to [email protected] Australian Age Points - (APP) are set for 50 = 10th Alltime Aus Age Time and 40 = 2011 Australian Age QT Points are only allocated to Australian Age Championship events with lowest age at 13/u Note that the lowest points in these rankings is 44 points For more information on the AAP, email [email protected] AAP Male 11 & Under 50 Free 1 26.94 LF Te Haumi Maxwell 11 NSW 12/06/2006 School Sport Australia Champ. 2 27.49 LF Kyle Chalmers 11 SA 6/06/2010 School Sport Australia Swimming Championships 3 27.53 LF Oliver Moody 11 NSW 6/06/2010 School Sport Australia Swimming Championships 4 27.93 LF Nicholas Groenewald 11 NUN 15/03/2009 The Last Blast 09' 5 27.97 LF Bailey Lawson 11 PBC 13/03/2009 2009 Swimming Gold Coast Championships 6*P 28.01 L Nicholas Capomolia 11 VIC 13/09/2009 School Sport Australia Swimming Championships 6*F 28.01 L Cody Simpson 11 QLD 1/12/2008 Pacific School Games 2008 Swimming 8 28.04 LF Anthony Truong 11 NSW 28/11/2005 Melbourne - Pacific School Games 9 28.23 LF Michael Buchanan 11 QLD 14/05/2001 Canberra - Aus Primary Schools 10 28.26 LF Samuel Ritchens 11 LCOV 16/01/2010 2010 NSW State 10/U-12 Years Age Championship Male 11 & Under 100 Free 1 59.49 LF Peter Fisher 11 NSW 8/05/1991 ? Tri Series 2 59.95 LF Oliver Moody 11 NSW 6/06/2010 School Sport Australia Swimming Championships 3 59.98 LF John Walz 11 QLD 11/01/1999 Brisbane - Jan 1999 4 1:00.39 LF Te Haumi Maxwell 11 NSW 12/06/2006 School Sport Australia Champ. -

The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces' and Indonesia's

The International Journal of the History of Sport ISSN: 0952-3367 (Print) 1743-9035 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fhsp20 The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces and Indonesia’s Relationship with the International Olympic Committee Friederike Trotier To cite this article: Friederike Trotier (2017): The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces and Indonesia’s Relationship with the International Olympic Committee, The International Journal of the History of Sport, DOI: 10.1080/09523367.2017.1281801 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2017.1281801 Published online: 22 Feb 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fhsp20 Download by: [93.198.244.140] Date: 22 February 2017, At: 10:11 THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF SPORT, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2017.1281801 The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces and Indonesia’s Relationship with the International Olympic Committee Friederike Trotier Department of Southeast Asian Studies, Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The Games of the New Emerging Forces (GANEFO) often serve as Indonesia; GANEFO; Asian an example of the entanglement of sport, Cold War politics and the games; Southeast Asian Non-Aligned Movement in the 1960s. Indonesia as the initiator plays games; International a salient role in the research on this challenge for the International Olympic Committee (IOC) Olympic Committee (IOC). The legacy of GANEFO and Indonesia’s further relationship with the IOC, however, has not yet drawn proper academic attention. -

Multi-Sport Competitions

APES 1(2011) 2:225-227 Šiljak, V and Boškan, V. : MULTI-SPORT COMPETITIONS ... MULTI-SPORT COMPETITIONS UDC: 796.09 (100) (091) (Professional peper ) Violeta Šiljak and Vesna Boškan Alfa University, Faculty of Management in Sport, Belgrade, Serbia Abstract Apart from the Olympic games, world championships, the university students games – The Universiade, there are many other regional sport movements organized as well. The World Games, the Asian Games, the Panamerican Games, the Commonwealth Games, the Balkan Games and so on, are some of multi-sport competitions all having the mutual features of competitions in numerous sports which last for several days. Some sports which are not a part of the Olympic Games programme are included into these world/regional games. These games are organized with the intention of impro- ving international sport/competitions. Keywords: Olympic games, World Games, students games, regional sports Introduction Games Association under the patronage of the Multi-sports competitions are organized sports International Olympic Committee. Some of the events that last several days and include competi- sports that were in the program of the World tion in great number of sports/events. The Olympic Games have become the Olympic disciplines (such Games as the first modern multi-sport event serve as triathlon), while some of them used to Olympic as a model for organizing all other major multi- sports in the past, but not any more (such as rope sports competitions. These several-day events are pulling). The selection of sports at the last World held in a host city, where the winners are awarded Games was done based on the criterion adopted by medals and competitions are mostly organized the IOC on August 12, 2004. -

Barshim Returns to Great Form with a Bang, Storms Into Final

Top coach Salazar barred from Worlds after doping ban PAGE 12 WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2019 © IAAF 2006 hosts Qatar to bid for 2030 Asian Games TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK Besides, the FIFA World Cup is DOHA all set to be staged in 2022 and one year later, the FINA World RECOGNISED as a destina- Championships are also sched- tion of world’s major sport- uled in Qatar. ing events, Doha – the capi- The 2006 Asian Games tal city of Qatar – first came turned out to be the best in into prominence in December history of the Olympic Council 2006 when it hosted the 15th of Asia. Though Qatar has been Asian Games. And now, Qatar hosting international events is aiming to host another edi- since early 1990s, the 2006 tion of these championships multiple sports continental in 2030. event saw heaps of all-round According to Qatar Olym- praise, and it is still referred to pic Committee (QOC) Secre- as a bench mark for the hosts. tary-General Jassim Rashid al Buenain, Qatar will make HOSTS OF THE ASIAN GAMES a formal expression of inter- Edition Year Host City Host Nation est for the bid of 2030 Asian I 1951 New Delhi India Games in Lausanne (Switzer- II 1954 Manila Philippines land) in January 2020 when III 1958 Tokyo Japan the Youth Olympic Games are IV 1962 Jakarta Indonesia held there. QOC Secretary-General Jassim Rashid al Buenain The 2006 Doha Asian Games opening ceremony at the Khalifa International Stadium. V 1966 Bangkok Thailand Al Buenain expressed VI 1970 Bangkok Thailand Doha’s desire to organise the in 424 events in 39 sports. -

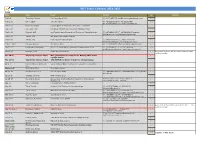

WTF Event Calendar 2014-2015 2014 Date Place Event Contact G Remark

WTF Event Calendar 2014-2015 2014 Date Place Event Contact G Remark Feb 8-9 Trelleborg, Sweden Trelleborg Open 2014 (T) +46709922594 [email protected] G-1 Feb 11-16 Luxor, Egypt 1st Luxor Open (T) +20222631737 (F) +20222617576 G-2 [email protected] / www.egypt-tkd.org Feb 13-16 Montreal, Canada Canada Open International Taekwondo Tournament G-1 Feb 18-24 Las Vegas, USA U.S Open International Taekwondo Championships G-2 Feb 20-22 Fujairah, UAE 2nd Fujairah Open International Taekwondo Championships (T) +97192234447 (F) +97192234474 fujairah- G-1 [email protected] / [email protected] Feb 21-23 Tehran, Iran 4th Asian Clubs Championships N/A Feb 24-26 Tehran, Iran 25th Fajr International Open (T) +982122242441 (F) +982122242444 G-1 [email protected] / www.fajr.iritf.org.ir Feb 27 - Mar 1 Manama, Bahrain 6th Bahrain Open (T) +73938888350 / [email protected] G-1 Mar 15-16 Eindhoven, Netherlands 41st Lotto Dutch Open Taekwondo Championships 2014 (T) +31235428867 (F) +31235428869 G-2 [email protected] / www.taekwondobond.nl Mar 15-17 Santiago, Chile South American Games G-1 Last event in March will be counted into the April ranking for GP1. Mar 20-21 Taipei City, Chinese Taipei WTF Qualification Tournament for Nanjing 2014 Youth N/A Olympic Games Mar 23-26 Taipei City, Chinese Taipei 10th WTF World Junior Taekwondo Championships N/A Apr 4-6 Santo Domingo, Dominican Santo Domingo Open International Taekwondo Tournament G-1 Rep. [Canceled] Kish Island, Iran West Asian Games G-1 Apr 11-13 Hamburg. Germany German Open -

Men's All-Time Top 50 World Performers-Performances

Men’s All-Time World Top 50 Performers-Performances’ Rankings Page 111 ο f 727272 MEN’S ALL-TIME TOP 50 WORLD PERFORMERS-PERFORMANCES RANKINGS ** World Record # 2nd-Performance All-Time +* European Record *+ Commonwealth Record *" Latin-South American Record ' U.S. Open Record * National Record r Relay Leadoff Split p Preliminary Time + Olympic Record ^ World Championship Record a Asian Record h Hand time A Altitude-aided 50 METER FREESTYLE Top 51 Performances 20.91** Cesar Augusto Filho Cielo, BRA/Auburn BRA Nationals Sao Paulo 12-18-09 (Reaction Time: +0-66. (Note: first South American swimmer to set 50 free world-record. Fifth man to hold 50-100 meter freestyle world records simultaneously: Others: Matt Biondi [USA], Alexander Popov [RUS], Alain Bernard [FRA], Eamon Sullivan [AUS]. (Note: first time world-record broken in South America. First world-record swum in South America since countryman Da Silva went 26.89p @ the Trofeu Maria Lenk meet in Rio on May 8, 2009. First Brazilian world record-setter in South America: Ricardo Prado, who won 400 IM @ 1982 World Championships in Guayaquil.) 20.94+*# Fred Bousquet, FRA/Auburn FRA Nationals/WCTs Montpellier 04-26-09 (Reaction Time: +0.74. (Note: first world-record of career, first man sub 21.0, first Auburn male world record-setter since America’s Rowdy Gaines [49.36, 100 meter freestyle, Austin, 04/81. Gaines broke his own 200 free wr following summer @ U.S. WCTs.) (Note: Bousquet also first man under 19.0 for 50 yard freestyle [18.74, NCAAs, 2005, Minneapolis]) 21.02p Cielo BRA Nationals Sao Paulo 12-18-09 21.08 Cielo World Championships Rome 08-02-09 (Reaction Time: +0.68. -

Men's Athlete Profiles 1 49KG – SIMPLICE FOTSALA – CAMEROON

Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games - Men's Athlete Profiles 49KG – SIMPLICE FOTSALA – CAMEROON (CMR) Date Of Birth : 09/05/1989 Place Of Birth : Yaoundé Height : 160cm Residence : Region du Centre 2018 – Indian Open Boxing Tournament (New Delhi, IND) 5th place – 49KG Lost to Amit Panghal (IND) 5:0 in the quarter-final; Won against Muhammad Fuad Bin Mohamed Redzuan (MAS) 5:0 in the first preliminary round 2017 – AFBC African Confederation Boxing Championships (Brazzaville, CGO) 2nd place – 49KG Lost to Matias Hamunyela (NAM) 5:0 in the final; Won against Mohamed Yassine Touareg (ALG) 5:0 in the semi- final; Won against Said Bounkoult (MAR) 3:1 in the quarter-final 2016 – Rio 2016 Olympic Games (Rio de Janeiro, BRA) participant – 49KG Lost to Galal Yafai (ENG) 3:0 in the first preliminary round 2016 – Nikolay Manger Memorial Tournament (Kherson, UKR) 2nd place – 49KG Lost to Ievgen Ovsiannikov (UKR) 2:1 in the final 2016 – AIBA African Olympic Qualification Event (Yaoundé, CMR) 1st place – 49KG Won against Matias Hamunyela (NAM) WO in the final; Won against Peter Mungai Warui (KEN) 2:1 in the semi-final; Won against Zoheir Toudjine (ALG) 3:0 in the quarter-final; Won against David De Pina (CPV) 3:0 in the first preliminary round 2015 – African Zone 3 Championships (Libreville, GAB) 2nd place – 49KG Lost to Marcus Edou Ngoua (GAB) 3:0 in the final 2014 – Dixiades Games (Yaounde, CMR) 3rd place – 49KG Lost to Marcus Edou Ngoua (GAB) 3:0 in the semi- final 2014 – Cameroon Regional Tournament 1st place – 49KG Won against Tchouta Bianda (CMR) -

The EU, Resilience and the MENA Region

REGION ENA THE EU, RESILIENCE The EU Global Strategy outlines an ambitious set of objectives to refashion the EU’s foreign and security policy. Fostering state and AND THE MENA REGION societal resilience stands out as a major goal of the strategy, con- HE M T ceived both as a means to enhance prevention and early warning and as a long-term investment in good governance, stability and prosperity. This book collects the results of a research project designed and implemented by FEPS and IAI exploring different understandings of resilience on the basis of six MENA state and societal contexts, mapping out the challenges but also positive reform actors and dynamics within them as a first step towards operationalizing the concept of resilience. U, RESILIENCE AND E FEPS is the progressive political foundation established at the European level. Created in 2007, it aims at establishing an intellec- tual crossroad between social democracy and the European project. THE As a platform for ideas and dialogue, FEPS works in close collabora- tion with social democratic organizations, and in particular national foundations and think tanks across and beyond Europe, to tackle the challenges that we are facing today. FEPS inputs fresh thinking at the core of its action and serves as an instrument for pan-Euro- pean, intellectual political reflection. IAI is a private, independent non-profit think tank, founded in 1965 on the initiative of Altiero Spinelli. IAI seeks to promote awareness of international politics and to contribute to the advancement of European integration and multilateral cooperation. IAI is part of a vast international research network, and interacts and cooperates with the Italian government and its ministries, European and inter- national institutions, universities, major national economic actors, the media and the most authoritative international think tanks. -

International-Multi-Sport-Games-With

INTERNATIONAL MULTI-SPORT GAMES WITH SQUASH 2018 OLYMPIC YOUTH GAMES PHOTO: AULIA DYAN PHOTO: International 2017 BOLIVARIAN GAMES 2018 ASIAN GAMES MULTI-SPORT GAMES WITH PHOTO: TONI VAN DER KREEK VAN TONI PHOTO: Squash 2018 COMMONWEALTH GAMES 2018 CENTRAL AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN GAMES By James Zug quash has been trying to get into the Olympic Games for decades. In 1986 the effort became focused when the International Olympic Committee recognized squash and the World Squash Federation applied for inclusion in the 1992 Barcelona Games. Campaigns have occurred ever since, in particular for the Beijing 2008, London 2012 and Rio 2016, as well as for the next three upcoming Summer Games. SThe push for the Olympics, however, often overshadows squash’s inclusion in numerous other international multi-sport events, some that you might know well and others slightly more obscure. Squash will be featured this month in the quadrennial Pan Ameri- can Games in Lima, and also the Pacific Games in Samoa and the Island Games in Gibraltar. Later this year, there is the African Games in Morocco in August, and the Southeast Asian Games in Philippines and the South Asian Games in Nepal in December. Many thousands of squash players, from top PSA professionals to amateurs of all ages, play in these games, building friendships and adding to their home nation’s medal count. The exposure of squash to wider audiences is tremendous, with media attention in the host and participating nations. The facilities that get built are fabulous legacies, particularly for host cities that are slightly off the beaten squash track—for example, the courts in Cartagena that were built for the 2006 Central PHOTO: © R. -

The Southeast Asian Games Federation

SOUTH EAST ASIAN GAMES FEDERATION CHARTER AND RULES DEFINITIONS 1 “NOC” means the National Olympic Committee of a South East Asian Country that has been accepted as a member of the South East Asian Games Federation. 2. “HOST NOC” means the National Olympic Committee that has been entrusted with the Honor of hosting the SEA Games. 3 “FEDERATION” means the South East Asian Games Federation. 4 “COUNCIL” means the Council of the South East Asian Games Federation. 5 “DELEGATE” means a person nominated to the Council of the South East Asian Games Federation by an NOC. 6 “EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE” means the Committee set up by the Council under Rule 11. 7 “SEA GAMES” means the South East Asian Games. 8 “SOUTH EAST ASIA” means the whole territory comprising the following countries: Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Timor Leste, Thailand, and Vietnam. FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES 1 The SEA Games shall be held every two years in between the years fixed for celebrations of the Olympic Games and the Asian Games. 2 The SEA Games shall be numbered from the first SEAP Games in Bangkok 1959. 3 The direction of the SEA Games shall be vested in the Council of the Federation. 4(a) The honor of holding the SEA Games shall be entrusted to the NOC of each country in rotation in alphabetical order, four (4) years in advance. (b) An NOC unable to accept the honor of holding the SEA Games in its turn shall inform the Council not later than one year after the Games had been awarded. -

Traditional Sports and Games 8 Wataru Iwamoto (Japan)

TAFISAMAGAZINE Traditional Sport and Games: New Perspectives on Cultural Heritage 4th Busan TAFISA World Sport for All Games 2008 Under the Patronage of 1 2008 Contact TAFISA Office Dienstleistungszentrum Mainzer Landstraße 153 60261 Frankfurt/Main GERMANY Phone 0049.69.136 44 747 Fax 0049.69.136 44 748 e-mail [email protected] http://www.tafisa.net Impressum Editor: Trim & Fitness International Sport for All Association (TAFISA) Editor-in-Chief: Prof. Dr. Diane Jones-Palm Editorial Assistant: Margit Budde Editorial Board: Dr. Oscar Azuero, Colombia, Wolfgang Baumann, Germany, Prof. Dr. Ju-Ho Chang, Korea, Comfort Nwankwo, Nigeria, Jorma Savola, Finland Production and layout: Gebr. Klingenberg Buchkunst Leipzig GmbH Distribution: 1500 ISSN: 1990-4290 This Magazine is published in connection with the 4th Busan TAFISA World Sport for All Games, Busan, Korea, 26.09. - 02.10.2008 under the Patronage of IOC, ICSSPE and UNESCO The TAFISA Magazine is the official magazine of TAFISA. It is published up to two times a year and issued to members, partners and supporters of TAFISA. Articles published reflect the views of the authors and not necessarily those of TAFISA. Reproduction of arti- cles is possible as long as the source is accredited. The TAFISA Magazine is published with the support of the German Federal Ministry of the Interior, City of Frankfurt, Commerzbank AG, Hessian State Ministry of the Interior and for Sport, German Olympic Sport Confederation, Gundlach Holding GmbH & Co. KG and Sport StadiaNet AG TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Editorial -

A Manual Designed to Expand Tobacco Free Sports at National, Regional and International Levels Contents

A Manual Designed to Expand Tobacco Free Sports at National, Regional and International Levels Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS_________________________________________________________5 MESSAGE FROM THE REGIONAL DIRECTOR_________________________________________7 1. INTRODUCTION____________________________________________________________9 1.1 TOBACCO USE IN THE REGION __________________________________________9 1.2 WHAT IS MEANT BY TOBACCO-FREE SPORTS______________________________10 WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data 1.3 WHY TOBACCO-FREE SPORTS___________________________________________11 Tobacco free sports. a manual designed to expand tobacco free sports at national, international and regional levels. 1.4 TOBACCO-UNHEALTHY FOR SPORTS_____________________________________11 1. Tobacco. 2. Sports. 1.5 SPORTING PERFORMANCE AND TOBACCO USE____________________________13 ISBN 92 9061 179 0 (NLM Classification: WA 754) 1.6 TOBACCO-FREE SUCCESSES____________________________________________13 © World Health Organization 2005 All rights reserved. 1.7 SUMMARY_________________________________________________________15 The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, 2. ACTION PLAN FOR TOBACCO-FREE SPORTS______________________________________15 city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps