Fantasy Magazine, August 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mediakit with Links.Indd

Strange. Beautiful. Shocking. Surreal. “One of the trailblazing publishers of short-form science fiction, fantasy, and horror.” — Jason Heller, The A.V. Club Mission Statement Apex Magazine (http://www.apex-magazine.com) has been called all of these things since its inception. For more than ten years, Apex has been dazzling readers with its originality, fearlessness, and commitment to the very best. A three-time Hugo nominee, Apex Magazine is regarded as a trailblazer in the field of science fiction. A self-proclaimed mash-up of science fiction, fantasy, and horror, Apex delivers on the adage that a short story can take you to the end of the galaxy and back before dinner. The Magazine Apex has given a megaphone to some of the most unique and com- pelling voices of the past decade. Now one of the most recognizable names in the industry, Apex has become one of the standards that all others try to meet. From its hard-edged science fiction to magical realism, Apex has something to satisfy every fantastic taste. A two- time winner of the Nebula Award for Best Short Story (2014, 2015) and four-time nominee, the magazine continues to provide readers with some of the most thought-provoking and diverse fiction in the genre. Apex Magazine provides a monthly podcast for listeners to hear their favorite stories at a moment’s notice. The magazine also pub- lishes poetry, and it has had numerous pieces nominated for the Rhysling Award. Never one to play it safe, Apex’s stories blur the line between sci- ence fact and science fiction. -

The Annual Report Clarion West Writers Workshop • 2018

The Annual Report clarion west writers workshop • 2018 To provide a high-quality Clarion West is a nonprofit literary Our Mission: organization and is committed to equal educational opportunity for opportunity. Although there are fine writers of speculative fiction science fiction and fantasy writers of all at the start of their careers. ethnicities, races, and genders, historically Speculative fiction (science fiction, the field has reflected the same prejudices fantasy, horror, magic realism, and found in the culture around it, leading to slipstream) gives voice to those who proportionately fewer successful writers explore societal and technological change, of color and women writers than white along with deeper considerations of male writers. Clarion West is dedicated to the underlying archetypes of human improving those proportions. experience. Clarion West brings new As an extension of its primary mission, writers to the field by providing a Clarion West seeks to make speculative transformative experience in the form of fiction available to the public, and thus an intensive workshop focusing on literary holds readings and other events that bring quality, diversity of viewpoints, range of speculative fiction writers and readers material, and other essential qualities. together. Looking over the previous year, I am so received the inaugural Special Award Executive thankful for all of the support from our for Community Building and community. As we strive to meet the needs Director's of today’s writers, I am always grateful for Inclusivity, highlighting the contribu- our volunteers: those that offer their time tions of our workshop staff and alumni. and personal vehicles, sit at information We had some staff changes in 2018 as Message tables, and join committees, as well as the well. -

Lightspeed Magazine, Issue 78 (November 2016)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 78, November 2016 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial, November 2016 SCIENCE FICTION Dinosaur Killers Chris Kluwe Under the Eaves Lavie Tidhar Natural Skin Alyssa Wong For Solo Cello, op. 12 Mary Robinette Kowal FANTASY Two Dead Men Alex Jeffers Shooting Gallery J.B. Park A Dirge for Prester John Catherynne M. Valente I've Come to Marry the Princess Helena Bell NOVELLA Karuna, Inc. Paul Di Filippo EXCERPTS The Genius Asylum Arlene F. Marks NONFICTION Media Review: Westworld The Geek’s Guide to the Galaxy Book Reviews, November 2016 Kate M. Galey, Jenn Reese, Rachel Swirsky, and Christie Yant Interview: Stephen Baxter The Geek’s Guide to the Galaxy AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS Chris Kluwe Lavie Tidhar J.B. Park Alyssa Wong Catherynne M. Valente Mary Robinette Kowal Helena Bell Paul di Filippo MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Stay Connected Subscriptions and Ebooks About the Lightspeed Team Also Edited by John Joseph Adams © 2016 Lightspeed Magazine Cover by Reiko Murakami www.lightspeedmagazine.com Editorial, November 2016 John Joseph Adams | 1064 words Welcome to issue seventy-eight of Lightspeed! We have original science fiction by Chris Kluwe (“Dinosaur Killers”) and Alyssa Wong (“Natural Skin”), along with SF reprints by Lavie Tidhar (“Under the Eaves”) and Mary Robinette Kowal (“For Solo Cello, op. 12”). Plus, we have original fantasy by J.B. Park (“Shooting Gallery”) and Helena Bell (“I’ve Come to Marry the Princess”), and fantasy reprints by Alex Jeffers (“Two Dead Men”) and Catherynne M. Valente (“A Dirge for Prester John”). All that, and of course we also have our usual assortment of author spotlights, along with our book and media review columns. -

The Secret Feminist Cabal

Winter 2010 Volume 6 The Aqueduct Gazette Top Stories Aqueduct Press Releases a New Collection Fall/Winter Releases by Gwyneth Jones G New Collection from Gwyneth Jones Imagination/Space: Essays and Talks on Fiction, Feminism, G The tale of feminist sf, from Technology, and Politics the beginning... Last year the Science Fiction Research As- The Secret Feminist Cabal sociation honored Gwyneth Jones with their by Helen Merrick Pilgrim Award for Lifetime Achievement, Read excepts for her consistently excellent critical writings from the Preface page 2 about science fiction. Gwyneth’s criticism has long been respected in feminist-sf circles; her previous collection of criticism, Deconstructing Special Features the Starships, was both eagerly anticipated and G Hanging out along the well-received. I recall snatching it off a table Aqueduct…, in the Dealers Room at WisCon—and later in the weekend finding myself Love at the City of Books in the position of being begged for a few hours with it by another con-goer by Kristin King because it had sold out. page 7 cont. on page 2 G The Shady Relationship between Lesbian and The Secret Feminist Cabal: Speculative Fiction by Carrie Devall A Cultural History of Science Fiction Feminisms page 3 by Helen Merrick G Read the Introduction to Aqueduct brings sf book-lovers a special Narrative Power treat for their winter reading. Written in edited by L. Timmel Duchamp elegant, lucid prose, The Secret Feminist Cabal page 8 will surely engage anyone interested in its subject matter, the inner workings of the -

Tor.Com October 2018

TOR.COM OCTOBER 2018 Exit Strategy The Murderbot Diaries Martha Wells The fourth book in Martha Wells' Murderbot Diaries, a wildfire science fiction phenomenon about an antisocial AI learning to care "I love Murderbot!" —Ann Leckie The fourth and final part of the Murderbot Diaries series that began with All Systems Red. FICTION / SCIENCE FICTION / Murderbot wasn’t programmed to care. So, its decision to help the only human ACTION & ADVENTURE who ever showed it respect must be a system glitch, right? Tor.com | 10/2/2018 9781250191854 | $16.99 / $22.50 Can. Hardcover | 160 pages | Carton Qty: 28 Having traveled the width of the galaxy to unearth details of its own murderous 8 in H | 5 in W transgressions, as well as those of the GrayCris Corporation, Murderbot is Other Available Formats: heading home to help Dr. Mensah—its former owner (protector? friend?) Ebook ISBN: 9781250185464 —submit evidence that could prevent GrayCris from destroying more colonists in its never-ending quest for profit. But who’s going to believe a SecUnit gone rogue? And what will become of it when it’s caught? PRAISE "I love Murderbot!" —Ann Leckie, author of Ancillary Justice "Clever, inventive, brutal when it needs to be, and compassionate without ever being sentimental." —Kate Elliott, author of the Spirit Walker trilogy "Endearing, funny, action-packed, and murderous." —Kameron Hurley, author of The Stars Are Legion MARTHA WELLS has written many fantasy novels, including The Wizard Hunters, Wheel of the Infinite, the Books of the Raksura series (beginning with The Cloud Roads and ending with The Harbors of the Sun), and the Nebula-nominated The Death of the Necromancer, as well as YA fantasy novels, short stories, and non-fiction. -

Progress Report Four

World Fantasy Convention 2014 6 November - 9 November 2014 Washington, D.C. Progress Report Four World Fantasy Convention 2014 6 November - 9 November 2014 Our gathering — the 40th World Fanasy Convention – will take place at the Hyatt Regen- cy Crystal City in Arlington, Virginia, and will culminate in a banquet where the 2014 World Fantasy Awards will be presented. Guests of Honor Guy Gavriel Kay Les Edwards Stuart David Schiff Special Guest Lail Finlay Toastmaster Mary Robinette Kowal World Fantasy Convention 2014 Post Office Box 314 Annapolis Junction, MD 20701-0314 worldfantasy2014.org • [email protected] Facebook: WorldFantasy40 • Twitter: @WorldFantasy40 Contact Sam Lubell at [email protected] to volunteer 1 Jane Yolen We regret to report Jane Yolen will not be able to be the Toastmaster for this year’s World Fantasy Convention. She is undergoing major back surgery that will have a six-month recovery period followed by six months of physical therapy. Jane had to cancel all of her 2014 travel plans and she is very sorry since she was looking forward to joining everyone at WFC 2014. Hugo-Award winning author, professional puppeteer, voice actor, and Emergency Holographic Toastmaster. In addition to co-hosting our Wednesday evening Scotch Tasting with Guy Gavriel Kay, Mary Robinette Kowal has kindly agreed take over Jane Yolen’s toast mastering duties for WFC 2014. Jane Yolen Exhibit There will be a special exhibit of Jane Yolen’s work featuring international editions and cover artwork for many of her novels. 2014 World Fantasy Lifetime Achievement Award Our heartfelt congratulations to Ellen Datlow and Chelsea Quinn Yarbro for winning the 2014 World Fantasy Lifetime Achievement Award! We will post the nominees for the other awards to our web site once the list has been published. -

Fantasy Magazine, July 2010

Fantasy Magazine Issue 40, July 2010 Table of Contents Perhaps this is Kushi’s Story by Swapna Kishore (fiction) Violets for Lee by Desirina Boskovich (fiction) The Seal of Sulaymaan by Tracy Canfield (fiction) The Stable Master’s Tale by Rachel Swirsky (fiction) Author Spotlight: Swapna Kishore Author Spotlight: Desirina Boskovich Author Spotlight: Tracy Canfield Author Spotlight: Rachel Swirsky About the Editor © 2010 Fantasy Magazine www.fantasy-magazine.com Perhaps this is Kushi’s Story Swapna Kishore Elder Sister places pebbles to mark people in her sand village. She pats walls in place. She smiles in her know- it-all way as if to remind me that it is she who will marry the headman’s son and decide what our tribe does—all because she was born an hour before me. When she stands back to admire her work, I kick it in. “Younger Sister, why?” She gives a mournful look. “You hadn’t posted guards,” I mock. “A city is more than fields and huts and granaries.” “Hmmm.” She flattens the sand and drags a twig to sketch a new plan, this time including watch towers. She cups her hands around moist sand to shape buildings again. I hate it when she doesn’t fight. She will take time to build anything worth kicking, so I turn to the Maasa river. The pebble I throw skims over the flat blue water, touching the surface once, twice, three times before it sinks. The air smells of river spray and fresh grass and ripe wheat—too peaceful for me. My dreams have soldiers flashing swords and cities full of buildings and the sounds of song and dance. -

The Apex Book of World SF: Volume 4 Free

FREE THE APEX BOOK OF WORLD SF: VOLUME 4 PDF Usman T Malik,Lavie Tidhar,Mahvesh Murad | 338 pages | 20 Aug 2015 | Apex Book Company | 9781937009335 | English | United States All books by Apex Publications We will ship it separately in 10 to 15 days. The landmark anthology series of international speculative fiction returns with volume 5 of The Apex Book of World SF. Cris Jurado joins series editor Lavie Tidhar to highlight the best speculative fiction from around the world. And much more. The fifth volume of the ground-breaking World SF anthology series reveals once more the uniquely international dimension of speculative fiction. Essay help magazine Research paper examples. Menu Login Register Cart 0. Twitter Facebook Instagram Login The Apex Book of World SF: Volume 4. Cart 0. Cover art and design by Sarah Anne Langton. His other works include the Bookman Histories trilogy, several novellas, two collections and a forthcoming comics mini-series, Adler. He currently lives in London. Cristina Jurado is a bilingual The Apex Book of World SF: Volume 4 and editor who writes in Spanish and English. You may also like Mirrorstrike. With her mother's blood fresh on her Breaking the World. InDavid Koresh predicted the end of the world. What if Return to the Lost Level. Cry Your Way Home. Cry Your Way Home brings together seventeen stories that delve Follow Us Twitter Facebook Instagram. Science fiction, fantasy, and horror books and eBooks – Apex Publications Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. -

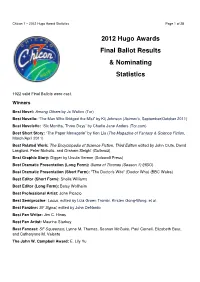

2012 Hugo Awards Final Ballot Results & Nominating Statistics

Chicon 7 – 2012 Hugo Award Statistics Page 1 of 28 2012 Hugo Awards Final Ballot Results & Nominating Statistics 1922 valid Final Ballots were cast. Winners Best Novel: Among Others by Jo Walton (Tor) Best Novella: “The Man Who Bridged the Mist” by Kij Johnson ( Asimov's , September/October 2011) Best Novelette: “Six Months, Three Days” by Charlie Jane Anders (Tor.com) Best Short Story: “The Paper Menagerie” by Ken Liu ( The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction , March/April 2011) Best Related Work: The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Third Edition edited by John Clute, David Langford, Peter Nicholls, and Graham Sleight (Gollancz) Best Graphic Story: Digger by Ursula Vernon (Sofawolf Press) Best Dramatic Presentation (Long Form): Game of Thrones (Season 1) (HBO) Best Dramatic Presentation (Short Form): "The Doctor's Wife" (Doctor Who) (BBC Wales) Best Editor (Short Form): Sheila Williams Best Editor (Long Form): Betsy Wollheim Best Professional Artist: John Picacio Best Semiprozine : Locus, edited by Liza Groen Trombi, Kirsten Gong-Wong, et al. Best Fanzine: SF Signal , edited by John DeNardo Best Fan Writer: Jim C. Hines Best Fan Artist: Maurine Starkey Best Fancast: SF Squeecast , Lynne M. Thomas, Seanan McGuire, Paul Cornell, Elizabeth Bear, and Catherynne M. Valente The John W. Campbell Award: E. Lily Yu Chicon 7 – 2012 Hugo Award Statistics Page 2 of 28 Best Novel – 1664 ballots counted First Place Among Others ( WINNER ) 421 424 493 585 769 Embassytown 324 324 392 492 608 Deadline 311 312 367 418 A Dance With Dragons 316 317 360 -

Asfacts Apr15.Pub

ASFACTS 2015 APRIL “V ARIED WEATHER ” S PRING ISSUE Winners will be announced at the Nebula Awards Ban- quet June 6 at the Palmer House Hilton, Chicago IL. In addition to his contributions to the genre, Niven has influenced the “fields of space exploration and technology.” The Grandmaster Award is given for “lifetime achievement VERNON AMONG 2014 N EBULA NOMINEES ; in science fiction and/or fantasy.” Jeffry Dwight will receive the 2015 Kevin O’Donnell Jr. Service to SFWA Award. NIVEN NAMED SFWA G RAND MASTER In late February, the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writ- 2015 H UGO AWARD FINALISTS ANNOUNCED ers of America released the final ballot for the 2014 Nebula Awards. The group also named Larry Niven the recipient of The finalists for the 2015 Hugo Awards were announced the Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award, citing his April 4 at Norwescon and three other conventions and online “invaluable contributions to the field of science fiction and via UStream, as well as via the Twitter feed and other social fantasy.” A full list of nominees, including Bubonicon 44 media of Sasquan, the 2015 Worldcon. Artist Guest Ursula Vernon, follows: Since then, the Hugo committee has decided that two Novel: The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison, nominees were not eligible, two other nominees have asked Trial by Fire by Charles E. Gannon, Ancillary Sword by Ann for their names to be removed from the ballot, and Connie Leckie, The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu, Coming Willis has withdrawn as an award presenter at the ceremony Home by Jack McDevitt, and Annihilation by Jeff Vander- – all due to controversy around the nominees. -

Locus-2017-10.Pdf

T A B L E o f C O N T E N T S October 2017 • Issue 681 • Vol. 79 • No. 4 50th Year of Publication • 30-Time Hugo Winner CHARLES N. BROWN Founder (1968-2009) Cover and Interview Designs by Francesca Myman LIZA GROEN TROMBI Editor-in-Chief KIRSTEN GONG-WONG Managing Editor MARK R. KELLY Locus Online Editor-in-Chief CAROLYN F. CUSHMAN TIM PRATT Senior Editors FRANCESCA MYMAN Design Editor LAUREL AMBERDINE ARLEY SORG Assistant Editors BOB BLOUGH JOSH PEARCE Editorial Assistants JONATHAN STRAHAN Reviews Editor TERRY BISSON LIZ BOURKE STEFAN DZIEMIANOWICZ GARDNER DOZOIS AMY GOLDSCHLAGER FAREN MILLER RICH HORTON Staffers at the Worldcon 75 Staff Weekend at the Messukeskus Convention Center KAMERON HURLEY RUSSELL LETSON I N T E R V I E WS ADRIENNE MARTINI COLLEEN MONDOR James Patrick Kelly: Alterations / 10 RACHEL SWIRSKY Annalee Newitz: Reprogramming / 32 GARY K. WOLFE Contributing Editors M A I N S T O R I E S / 5 ALVARO ZINOS-AMARO Jerry Pournelle (1933 - 2017) • 2016 Sidewise Awards Winners • 2017 Dragon Awards Winners • Roundtable Blog Editor Joan Aiken Prize • 2017 National Book Award Longlist • SFWA Call for Grants • Women Injured WILLIAM G. CONTENTO at Dragon Con • 2017 Man Booker Shortlist Computer Projects Locus, The Magazine of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Field (ISSN 0047-4959), is published monthly, at $7.50 TH E D A T A F I L E / 7 per copy, by Locus Publications, 1933 Davis Street, Suite 297, San Leandro CA 94577. Please send all mail to: Locus Publications, 1933 Davis Street, Suite 297, San 2017 WSFA Small Press Award Finalists • Sarem Removed from Times List • Patterson Grants • Leandro CA 94577. -

A Fun Month. Oasfis Was Represented at the UCF Bookfair. the Picnic

Volume 24 Number 12 Issue 294 May 2012 A WORD FROM THE EDITOR The 2012 Hugo and John W. Campbell Award Nominees A fun month. OASFiS was represented at the (source Chicon 7 website) UCF Bookfair. The picnic was great. Thank You 1101 valid nominating ballots were received and counted. Susan Cole and Bonny Bealle and everyone who Best Novel (932 ballots) helped out. The Hugo Nominees were announced Among Others by Jo Walton (Tor) online on April 7. There are a lot of great nominees. A Dance With Dragons by George R. R. Martin (Bantam Spectra) Deadline by Mira Grant (Orbit) Next month we will have the Nebula winners, Embassytown by China Miéville (Macmillan / Del Rey) some pictures from OASIS and a review or 2. Leviathan Wakes by James S. A. Corey (Orbit) Till next time. Best Novella (473 ballots) Countdown by Mira Grant (Orbit) . “The Ice Owl” by Carolyn Ives Gilman (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, November/December 2011) “Kiss Me Twice” by Mary Robinette Kowal (Asimov's, June 2011) “The Man Who Bridged the Mist” by Kij Johnson (Asimov's, September/October 2011) “The Man Who Ended History: A Documentary” by Ken Liu (Panverse 3) Silently and Very Fast by Catherynne M. Valente (Clarkesworld / WSFA) Best Novelette (499 ballots) Leviathan Wakes “The Copenhagen Interpretation” by Paul Cornell (Asimov's, July by 2011) James A. Corey “Fields of Gold” by Rachel Swirsky (Eclipse Four) (Daniel Abraham & Ty Franck) “Ray of Light” by Brad R. Torgersen (Analog, December 2011) The Human population is expanding in the Solar “Six Months, Three Days” by Charlie Jane Anders (Tor.com) System.