The Professional World in David Mamet's Glengarry Glen Ross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

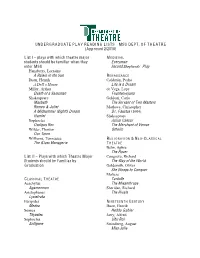

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

Ebook Download the Plays, Screenplays and Films of David

THE PLAYS, SCREENPLAYS AND FILMS OF DAVID MAMET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Steven Price | 192 pages | 01 Oct 2008 | MacMillan Education UK | 9780230555358 | English | London, United Kingdom The Plays, Screenplays and Films of David Mamet PDF Book It engages with his work in film as well as in the theatre, offering a synoptic overview of, and critical commentary on, the scholarly criticism of each play, screenplay or film. You get savvy industry tips and strategies for getting your screenplay noticed! Mamet is reluctant to be specific about Postman and the problems he had writing it, explaining. He shrugs off the whispers floating up and down the Great White Way about him selling out and going Hollywood. Contemporary playwright David Mamet's thought-provoking plays and screenplays such as Wag the Dog , Glengarry Glen Ross for which he won the Pulitzer Prize , and Oleanna have enjoyed popular and critical success in the past two decades. The Winslow Boy, Mamet's revisitation of Terence Rattigan's classic play, tells of a thirteen-year-old boy accused of stealing a five-shilling postal order and the tug of war for truth that ensues between his middle-class family and the Royal Navy. House of Games is a psychological thriller in which a young woman psychiatrist falls prey to an elaborate and ingenious con game by one of her patients who entraps her in a series of criminal escapades. Paul Newman plays Frank Calvin, an alcoholic and disgraced Boston lawyer who finds a shot at redemption with a malpractice case. I Just Kept Writing. The impressive number of essays , novels , screenplays , and films that Mamet has produced They might be composed and awesome on the battlefield, but there is a price, and that is their humanity. -

Advertising Sales

"It is a thrill to see David Mamet’s “Glengarry Glen Ross” on this season’s theater roster..." -- Lansing City Pulse August 12, 2015 "...even the silent moments grab the audience and keep them intently focused." --Bridgette Redman, Encore Michigan review of Ixion's Topdog/Underdog "...a thrill to watch." --Tom Helma, Lansing City Pulse review of Ixion's The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds Be a part of the excitement! Advertise with Ixion After a critically acclaimed inaugural season, Ixion theatre ensemble is diving into its second. Featuring world and regional premieres, and a dynamic revival; this season promises to entertain, challenge and excite audiences. Equally exciting is our new home, the Robin Theater. Seating nearly a hundred people per performance, this space offers an intimate opportunity to enjoy the arts. You can be a part of our second season by advertising in our show programs. Imagine connecting with a dynamic arts organization; their patrons committed to Sineh Wurie the community; and celebrating the revitalization of Lansing's REO Town! Nominated for Best Lead Actor by Lansing City Pulse & Encore Michigan in Attached is an advertising order sheet, which details ad specs and pricing. Please Topdog/Underdog contact us if you have any questions. If you are interested in underwriting a particular show or discussing other advertising opportunities, please contact our Artistic Director, jeff croff, via phone, 715.775.4246, or email [email protected]. www.ixiontheatre.com Find us on Facebook and Google+ -

Theatre of Power: Conflicts, Resistance and Foucauldian Power

國立中山大學外國語文研究所 碩士論文 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRAGUATE INSTITUTE OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE NATIONAL SUN YAT -SEN UNIVERSITY 指導教授: 王儀君 Advisor: Professor Wang I-Chun 題目:權力劇場: 大衛‧馬梅特之《房地產大亨》及《美國水牛》 中的衝突、反抗與傅柯式權力觀 Title: Theatre of Power: Conflicts, Resistance and Foucauldian Power in David Mamet's Glengarry Glen Ross and American Buffalo 研究生: 陳宛伶 撰 By: Chen Wan-Ling 中華民國八十九年六月 June 2000 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I’ve learned that the most precious gift I’ve received is the warm concern and constant encouragement from the following people on my way of bringing this thesis to fulfillment. First and foremost, my gratitude goes to Professor Wang I-chun, my advisor. Without her patient guidance and perceptive advice, I could never be out of the impasse in the process of my thesis-writing. I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my oral examiners, Professor Wu Hsin-fa and Professor Liao Pen-shui, whose inspiring questions and invaluable suggestions help better this thesis. I am grateful to my sworn confidants for their lasting friendship and immense support: to Emily Wu, for her steady care and understanding; to Sharon Tseng and Joan Lin, for their collecting important resources; to Gavin Wong and Vincent Tsai, for their careful proofreading at the final stage of the draft; to Leo Chen, Jackie Chen and Irene Wang, for their continual assistance. I wish to thank my musketeers, as well as forever friends, Pao-i Hwang and Grace Lai, for their cherished companionship. I also owe my good friends Ashlee Tai, Gloria Tsai and Jay Lee a great deal. -

Sidney Flack Height: 5’ 9” SAG-AFTRA Eligible 155 Lbs

Sidney Flack Height: 5’ 9” SAG-AFTRA Eligible 155 lbs. Hair: Gray has current passport Eyes: Blue and drivers license FILM Impropriety Supporting Nadeem Soumah, Dir. Dotty And Soul (Starring Leslie Uggams) Supporting Adam Saunders, Dir. Thirteen Minutes (Starring Paz Vega) Supporting Lindsay Gossling, Dir. In Sickness & In Health (Short) Supporting Chris Oz McIntosh, Dir. Dandelion (Short) Lead Jörg Viktor Steins-Lauss, Dir. Jade Black Major Supporting Terry Spears, Dir. The Last Exorcist Supporting Robin Bain, Dir. Hells Belle Supporting Terry Spears, Dir. MONO: An Anthology: Danger Boy Supporting Jacob Leighton Burns, Dir. Empyrean Supporting Amiel Courtin-Wilson, Dir. Tempo (Short) Supporting Lead Brian Lawes, Dir. The Harvesters Supporting Nick Sanford, Dir. Children of The Corn: Runaway Supporting John Gulager, Dir. Gosnell (Starring Dean Cain) Supporting Nick Searcy, Dir. The Foreverlands (short) Supporting Kyle Kauwika Harris, Dir. Effie (short) Supporting Lead Michael Cunningham, Dir. T. V. The Battle Of Honey Springs Star Pantheon Digital, Bryan Beasley, Dir. In The Gap: Deborah, The Cost of Freedom Star TBN, Jonathan Coussens, Dir. Murder Made Me Famous: 2 episodes Co-Star AMS Pictures, ReelzChannel - The Dating Game Killer Drew Feldman, Dir. - Robert Durst Katie Dunn, Dir. Price of Fame: Johnny Depp Co-Star AMS Pictures, ReelzChannel Brad Osborne, Dir. Annihilator (pilot trailer) Supporting Bat Bridge Entertainment Scandal Made Me Famous: 2 eps. Co-Star AMS Pictures, ReelzChannel - Jessica Hahn Adam Dietrich, Dir. - Anna Nicole -

The Tenth Annual William Kemp Symposium for Majors in English, Linguistics, & Communication

The Tenth Annual William Kemp Symposium for Majors in English, Linguistics, & Communication Thursday, April 24, 2014 8:00-9:15 SESSION I—American Drama since 1945 in Performance (Combs 111) 1. Dylan Lockwood (and friends), Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? by Edward Albee (video) 2. Nathan Bemis, Sam Relken, and Claire Winkler, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? by Edward Albee (live performance) 3. Courtney Rampey (and friends), Glengarry Glen Ross by David Mamet (video) 4. Amanda Riffe (and friends), The Heidi Chronicles by Wendy Wasserstein (video) 5. Megan Champion and Ashley Most, Fucking A by Suzan-Lori Parks (video) 6. Bethany Alley, Conor Murphy, and Sara Weinstein, The Glass Menagerie by Tennessee Williams, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? by Edward Albee, ’night, Mother by Marsha Norman, and Angels in America by Tony Kushner (video) Chair: Gary Richards 9:30- 10:45 SESSION II—Papers from "After Books" (Combs 114) Chair: Zach Whalen SESSION III—Six Poets: Poems from 304 (Combs 322) Creative works by Virginia Cox, Amanda Halprin, Stephenie Duncan, Lincoln Dunn, Keiera Lewis, and Robert Kingsley Chair: Luke Johnson 11:00-12:15 SESSION IV—Poems from 470A: Poetry Seminar (Combs 114) Creative works from 15 student poets Chair: Jon Pineda SESSION V—Social Media at UMW (Combs 112) Social Media Campaign: Promoting the UMW Multicultural Fair Students in COMM 370: Social Media developed and implemented a social media campaign for the Multicultural Fair. In this presentation, students from the class will discuss how to plan a social media campaign, phases of implementation, and how they helped to promote and document this year’s Multicultural Fair SMH 101: Finishing the Social Media Handbook for College Students The Spring 2013 COMM 370: Social Media class started a very ambitious project – to create an iPad book called SMH 101: The Social Media Handbook for College Students. -

English 5327 Twentieth Century American Drama: Family, History, and the American Dream Mon – Thurs, 10:30 – 12:30, Summer I 2008

English 5327 Twentieth Century American Drama: Family, History, and the American Dream Mon – Thurs, 10:30 – 12:30, Summer I 2008 Dr. Laurin R. Porter Office: 409 Carlisle Hall Phone: 817-272-2693 (during office hours and voice mail), 817-274-3075 (home) FAX: 817-272-2718 Email: [email protected] (home email: [email protected]) Office hours: Mon – Thurs, 10 – 10:30, after class, and by appointment Plays (in order): O’Neill, Eugene: The Iceman Cometh Long Day’s Journey Into Night A Moon for the Misbegotten A Touch of the Poet Miller, Arthur: Death of a Salesman Hansberry, Lorraine: A Raisin in the Sun Smith, Anna Devere: Twilight: The Rodney King Episode (in class video) Albee, Edward: Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Shepard, Sam, Buried Child Mamet, David: Glengarry Glen Ross Kushner, Tony: Angels in America, Part One: Millennium Approaches Hwang, David Henry: M. Butterfly Hellman, Lillian: The Little Foxes Williams, Tennessee: A Streetcar Named Desire Horton Foote: Orphans’ Home Cycle, Vols. I, II, and III Young Man from Atlanta The Last of the Thorntons Wilson, August: The Piano Lesson Schedule: May 27 Introduction to the class; theory, terminology, and critical methodology Readings (electronic reserve): Aristotle, Poetics; Martin Esslin, An Anatomy of Drama, chapters 2 & 3; Walter Kerr, Tragedy and Comedy, chapter 2; Thomas E. Porter, Myth and Modern American Drama, chapter 1. 2 May 28 The Iceman Cometh May 29 Long Day’s Journey June 2 A Moon for the Misbegotten June 3 A Touch of the Poet June 4 Death of a Salesman June 5 Raisin in the Sun and Twilight (in class video) June 9 Virginia Woolfe June 10 Buried Child June 11 Glengarry Glen Ross (Dr. -

Angels in America

Angels in America Part One Millennium Approaches Part Two Perestroika Belvoir presents Angels in America A Gay Fantasia on National Themes Part One Millennium Approaches Part Two Perestroika By TONY KUSHNER Director EAMON FLACK This production of Angels in America opened at Belvoir St Theatre on Saturday 1 June 2013. It transferred to Theatre Royal, Sydney, on Thursday 18 July 2013. Set Designer With MICHAEL HANKIN The Angel / Emily Costume Designer PAULA ARUNDELL MEL PAGE Louis Ironson Lighting Designer MITCHELL BUTEL NIKLAS PAJANTI Roy M. Cohn Associate Lighting Designer MARCUS GRAHAM ROSS GRAHAM Harper Amaty Pitt Composer AMBER McMAHON ALAN JOHN Prior Walter Sound Designer LUKE MULLINS STEVE FRANCIS Rabbi Isidor Chemelwitz / Hannah Assistant Director Porter Pitt / Ethel Rosenberg / Aleksii SHELLY LAUMAN ROBYN NEVIN Fight Director Belize / Mr Lies SCOTT WITT DEOBIA OPAREI American Dialect Coach Joseph Porter Pitt PAIGE WALKER-CARLTON ASHLEY ZUKERMAN Stage Manager All other characters are played by MEL DYER the company. Assistant Stage Manager ROXZAN BOWES Angels in America is presented by arrangement with Hal Leonard Australia Pty Ltd, on behalf of Josef Weinberger Ltd of London. Angels in America was commissioned by and received its premiere at the Eureka Theatre, San Francisco, in May 1991. Also produced by Centre Theatre Group/ Mark Taper Forum of Los Angeles (Gordon Davidson, Artistic Director/Producer). Produced in New York at the Walter Kerr Theatre by Jujamcyn Theatres, Mark Taper Forum with Margo Lion, Susan Quint Gallin, Jon B. Platt, The Baruch-Frankel-Viertel Group and Frederick Zollo in association with Herb Alpert. PRODUCTION THANKS José Machado, Jonathon Street and Positive Life NSW; Tia Jordan; Aku Kadogo; The National Association of People with HIV Australia. -

Shame: Its Place in Life and American Drama

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 2019 Shame: Its Place in Life and American Drama Lauren Elisabeth Terry Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Terry, Lauren Elisabeth, "Shame: Its Place in Life and American Drama" (2019). Honors Theses. 735. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/735 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Senior Thesis Approval This Honors thesis entitled "Shame: Its place in life and American drama" written by LAUREN ELISABETH TERRY and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion of the Carl Goodson Honors Program meets the criteria for acceptance and has been approved by the undersigned readers. Christina Johnson, thesis director Stephanie Faat:~-Mwrry, second reader Dr. Eli'zabeth Kelly, third read~r Dr. Barbara Pemberton, Honors Program director April 20th, 2019 lerry 1 1 Shame: Its place in life and American drama An exploration of the longevity and universality of shame Introduction How a TED Talk changed my life I spent my twenty-second birthday driving six hours by myself through the back roads of Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. I was traveling to Hattiesburg, Mississippi to interview at the University of Southern Mississippi for their MFA Theatre Directing program. -

David Mamet's Theory on the Power and Potential of Dramatic Language Rodney Whatley

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Mametspeak: David Mamet's Theory on the Power and Potential of Dramatic Language Rodney Whatley Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE AND DANCE MAMETSPEAK: DAVID MAMET’S THEORY ON THE POWER AND POTENTIAL OF DRAMATIC LANGUAGE By RODNEY WHATLEY A Dissertation submitted to the School of Theatre in partial fulfillment requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester 2011 Rodney Whatley defended this dissertation on October 19, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Mary Karen Dahl Professor Directing Dissertation Karen Laughlin University Representative Kris Salata Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................................v 1. CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION...................................................................................1 1.1 Rationale........................................................................................................................3 1.2 Description of Project....................................................................................................4 -

Drama Winners the First 50 Years: 1917-1966 Pulitzer Drama Checklist 1966 No Award Given 1965 the Subject Was Roses by Frank D

The Pulitzer Prizes Drama Winners The First 50 Years: 1917-1966 Pulitzer Drama Checklist 1966 No award given 1965 The Subject Was Roses by Frank D. Gilroy 1964 No award given 1963 No award given 1962 How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying by Loesser and Burrows 1961 All the Way Home by Tad Mosel 1960 Fiorello! by Weidman, Abbott, Bock, and Harnick 1959 J.B. by Archibald MacLeish 1958 Look Homeward, Angel by Ketti Frings 1957 Long Day’s Journey Into Night by Eugene O’Neill 1956 The Diary of Anne Frank by Albert Hackett and Frances Goodrich 1955 Cat on a Hot Tin Roof by Tennessee Williams 1954 The Teahouse of the August Moon by John Patrick 1953 Picnic by William Inge 1952 The Shrike by Joseph Kramm 1951 No award given 1950 South Pacific by Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein II and Joshua Logan 1949 Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller 1948 A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams 1947 No award given 1946 State of the Union by Russel Crouse and Howard Lindsay 1945 Harvey by Mary Coyle Chase 1944 No award given 1943 The Skin of Our Teeth by Thornton Wilder 1942 No award given 1941 There Shall Be No Night by Robert E. Sherwood 1940 The Time of Your Life by William Saroyan 1939 Abe Lincoln in Illinois by Robert E. Sherwood 1938 Our Town by Thornton Wilder 1937 You Can’t Take It With You by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman 1936 Idiot’s Delight by Robert E. Sherwood 1935 The Old Maid by Zoë Akins 1934 Men in White by Sidney Kingsley 1933 Both Your Houses by Maxwell Anderson 1932 Of Thee I Sing by George S. -

Glengarry Glen Ross, Prairie Du Chien, the Hawl, Speed-The-Plow V.3 Ebook

FREEMAMET PLAYS: GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS, PRAIRIE DU CHIEN, THE HAWL, SPEED-THE-PLOW V.3 EBOOK David Mamet | 192 pages | 23 Sep 1996 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780413687500 | English | London, United Kingdom Mamet Plays: 3 Duck Variations: "A brilliant little play about two old men sitting on a park bench discussing ducks" (Guardian); Sexual Perversity in Chicago, bar- room banter Churchill Plays: "Softcops"; "Top Girls"; "Fen"; "Serious Money" v.2 Mamet Plays: "Glengarry Glen Ross", "Prairie Du Chien", "The Hawl", "Speed-the-plow" v 3 00 North Z eeb R oad. Ann Arbor of the pool hall was the intersection of two American Loves: the the-Plow, Mamet's only full-length play since Glengarry Glen Ross, deals Besides Speed-the-Plow, Mamet's recent original plays have tended to Prairie du Chien stands as a bridge between The Shawl and House of. Be the first to ask a question about The Shawl & Prairie du Chien Glengarry Glen Ross by David Mamet American Buffalo by David Mamet On Film by David Mamet True and False by David Mamet Speed-the-Plow by David Mamet Prairie Du Chien: 3 stars However, The Shawl was an excellent, short, little play. StageAgent Distance Learning Hub 3 00 North Z eeb R oad. Ann Arbor of the pool hall was the intersection of two American Loves: the the-Plow, Mamet's only full-length play since Glengarry Glen Ross, deals Besides Speed-the-Plow, Mamet's recent original plays have tended to Prairie du Chien stands as a bridge between The Shawl and House of.