Traipsing the Old Stomping Grounds: the First Three Stories of a Novel-In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona 500 2021 Final List of Songs

ARIZONA 500 2021 FINAL LIST OF SONGS # SONG ARTIST Run Time 1 SWEET EMOTION AEROSMITH 4:20 2 YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC/DC 3:28 3 BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY QUEEN 5:49 4 KASHMIR LED ZEPPELIN 8:23 5 I LOVE ROCK N' ROLL JOAN JETT AND THE BLACKHEARTS 2:52 6 HAVE YOU EVER SEEN THE RAIN? CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL 2:34 7 THE HAPPIEST DAYS OF OUR LIVES/ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO 5:35 8 WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE GUNS N' ROSES 4:23 9 ERUPTION/YOU REALLY GOT ME VAN HALEN 4:15 10 DREAMS FLEETWOOD MAC 4:10 11 CRAZY TRAIN OZZY OSBOURNE 4:42 12 MORE THAN A FEELING BOSTON 4:40 13 CARRY ON WAYWARD SON KANSAS 5:17 14 TAKE IT EASY EAGLES 3:25 15 PARANOID BLACK SABBATH 2:44 16 DON'T STOP BELIEVIN' JOURNEY 4:08 17 SWEET HOME ALABAMA LYNYRD SKYNYRD 4:38 18 STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN LED ZEPPELIN 7:58 19 ROCK YOU LIKE A HURRICANE SCORPIONS 4:09 20 WE WILL ROCK YOU/WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS QUEEN 4:58 21 IN THE AIR TONIGHT PHIL COLLINS 5:21 22 LIVE AND LET DIE PAUL MCCARTNEY AND WINGS 2:58 23 HIGHWAY TO HELL AC/DC 3:26 24 DREAM ON AEROSMITH 4:21 25 EDGE OF SEVENTEEN STEVIE NICKS 5:16 26 BLACK DOG LED ZEPPELIN 4:49 27 THE JOKER STEVE MILLER BAND 4:22 28 WHITE WEDDING BILLY IDOL 4:03 29 SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL ROLLING STONES 6:21 30 WALK THIS WAY AEROSMITH 3:34 31 HEARTBREAKER PAT BENATAR 3:25 32 COME TOGETHER BEATLES 4:06 33 BAD COMPANY BAD COMPANY 4:32 34 SWEET CHILD O' MINE GUNS N' ROSES 5:50 35 I WANT YOU TO WANT ME CHEAP TRICK 3:33 36 BARRACUDA HEART 4:20 37 COMFORTABLY NUMB PINK FLOYD 6:14 38 IMMIGRANT SONG LED ZEPPELIN 2:20 39 THE -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Mpower You Magazine Q: What Is Your Name? A: My Name Is Danny Grewcock

A forum for empowerment and change MpowerIssue 2 you April/May 2010 An Actionwork Magazine Issue 2 April/May 2010 An Actionwork Magazine Learning to love your looks Living with epilepsy The psychology of bullying Drive for peace Getting bullied to experience empowerment - Film production with young people - Interactive workshops -Issue based Theatre in Education Recent clients include Norwich Playhouse UK, Anti-Bullying Al- liance (ABA), Government De- partments, (eg DFES, DOE)British Council, Regional and Borough Councils, Kyoto University, the Dawn Center Japan, University of London, Whitechapel Hospital, The Norwegian Institute of Dramath- erapy, Belmarsh prison, Exeter Uni- versity, schools & youth centres across the UK. We don’t just talk we do Actionwork Actionwork comes to you. We travel the length and breadth of Theatre - Film - Education the country and to many destina- tions abroad. Please contact us Action = The causation of change around chatting about a topic, for further details. by the exertion of power actually get in to it. Live your topic, document it, draw inspira- We want to hear from you. Work = Accomplishment through tion from it, feel the vibes of it, action activities tune in to it. Take your thoughts Actionwork, PO Box 433, WSM, BS24 and ideas on to a new level. Find 0WY, England UK Actionwork makes films and new angles of experience and produces theatre. Also check out expression. Feel the force! Tel: 01934 815163 our creative workshops & other Website: www.actionwork.com educational sessions. Make a film, learn how to use a camera, direct actors or act Actionwork specialises in tack- yourself. -

Winter Storm 2020 Brings Damages to LIBC Administrative Building Continued from Page

Xwlemi Nation News January 2020 Lummi Communications - 2665 Kwina Road - Bellingham, Washington 98226 The Protect ICWA Campaign Community Urges Federal Appeals Notices Court to Affirm ICWA’s Constitutionality Following Oral Arguments in Brackeen v. Bernhardt NEW ORLEANS, January will affirm ICWA’s strong families.” 22, 2020—Following today’s constitutional grounding. "There has been an United States Fifth Circuit ICWA protects children in overwhelming amount of Court of Appeals oral state child welfare systems resources coming forward arguments in the Brackeen and helps them remain to support the Indian Community meetings Meetings 3) Emergency v. Bernhardt case, the Protectconnected to their families, Child Welfare Act. We Disaster Notices. Anyone ICWA Campaign, consisting cultures, and communities.” should be spending our and events are posted of the National Indian “NCAI applauds the resources protecting Indian regularly on social media interested in receiving text at Lummi Communications messages for one or all Child Welfare Association, strong advocacy of the children and not fighting the National Congress of intervening tribes and interest groups that seek to facebook page. Any changes, the above text messaging systems call or email your American Indians, the the federal government, dismantle the government- delays, cancellations, or Association on American as Indian Country’s to-government relationship reschedules will also be name, phone number and Indian Affairs, and the trustee, in defending the between the United States posted there. Additionally, phone provider (example: Lummi Nation has set up on Native American Rights constitutionality of the Indian and Tribes. The Fifth Verizon, Boost, T Mobile, Sprint, AT& T, etc.) to lummi Fund, issued the following Child Welfare Act before the Circuit will be on the righttheir website lummi-nsn.gov communications at julieaj@ statements: entire Fifth Circuit Court side of history protecting a calendar of events (please “We look forward to of Appeals this morning,” Indian children, and by see picture above). -

Pledgers Age Has Raised Some Problems for Sider Ourselves Law Enforcement Sibly." by Michael Taviss Those in Charge of Officers of Massachusetts

Continuous A_n> MIT| NerJs Servic6 Cambridge Since 1881 ,Massachusetts Volume 99, Number 27 . Friday. August 31, 1979 Search or new dean not yet cc,mpneted By Steven Solnick mittee. which has come this far, TIthe absence of a new Dean for be allowed to complete its Student Affairs (DSA) will deliberations." probably be the most striking French said that the advisory feature of the newly reorganized committee would not meet again Deans' Office which greets until September 7 and it was un- freshmen today. clear whether that meeting would The Advisory Committee on prove sufficient to conclude their the selection of a new dean, business. Since the list of can- chaired by Professor A. P. didates must then be evaluated by French, has not yet "concluded the Chancellor, it seems unlikely the process" which will eventually the new dean will be selected result in a list of two to six can- before the end -of September. didates to be presented to the Simonides said the new dean Ii Chancellor. According to Vice would take office immediately, IIi President Constantine Simonides, although commitments to his cur- who conducted- a review of the rent position could delay his ac- Office of-the Dean for Student turlly assuming duties. French Affairs (OSDA) last year, '"rl is Assistant Dean Bonny Kellerman- will be leaving the Office of Freshman Advising for another blamed many of the delays in the vitally important that the Com- process on difficulties in assembl- 4 post in the Dean's Office. (Photo by 'Steve Solnick) I ing the committee and applicants IiI over the summer. -

Superpowers to Talk Again on Arms Cuts

J i FOCLS : \ ‘Ahwcr auflier Sox not looMIng vtsHs Bolton at podt faiuroo ... png* 0 I w 9 m 0 tfm b ig p t f e h 0e k M f F vow iMvo Moat oxporlonc# (portOfMl Inlury fMlotW bwt net roqufrotf, but knowlotfoo of court otoodlnvi a musf> iHauflirfitrr H m lh ) v^ncbe'^le'" A City of Village Charm I F vow art a oootf typist I F vow wont fop oelorv with vnllmlfedootenflel I F vow wist* to bo ooproclototf 30 Cents WE WANT YOU W# novo roconflv adOad porsonnof, bwt duo to oxcoptlonol orowfb, aro dosirous of add "Tiarasaf™* 0 ing m art. Yoorlv bonus, modleol bonofits ond Donslon offorod. Coll Doris Luotlon, CsiHsr, o « MOM Superpowers Ebonstoln & Ebonsfoln, P.C. StS4)t66. ttr, CT to iMor onO cotwidSr m« Miowino itoWtimM: yi!?i!V“ Aww»* Pwtwiriais - sesctsi •sessnse- ls tm sv gy.*!OCfEfl rTy.'nTr'yr,*rMUffllM nfMWtfffklll Mllftip #Ai%tamntmtcmttf^ WSMPftiM MAIUMB Ain ItMe^ known OT M V Jollant Tvrnpike, else known os porcef t N CUSTOMER SERVICE union Fontf industriol Fork. * to talk again i m i f u m m C Snhw 2Krn«»r<mfremjSSTSSdbnSfe $ REPRESENTATIVE Soles Person/Plorol At- C Moncbester-For sole by m Oer«Ker*Sfr»er**^ idewtWied « tn M i( 0pp«tMNr slstont. Full or port time owner,? room Cope. Mint All reed esfote advertised 3 and 4 room oportmenls, for flower ond offt shop. In Ihe AAeeichesfer Herald condition. 3 bedrooms, Is subfeef to the Fair no oppltanc«s,no pets,se- Appiv In person of Flower flrepioce, rec room with curftv,call 848-2438. -

Event Cancelled

Tel:STEVENS 603-542-8987 • email: [email protected] • Web: www.StevensAlumniNH.com School • Facebook: Alumni Association Newsletter The Oldest Active High School Alumni Association in the Country www.stevensalumninh.com Tel: 603-542-8987 • email: [email protected] • Web: www.StevensAlumniNH.com • Facebook: www.facebook.com/stevensalumninh Stevens Alumni Day 2019 assisted by Claremont lights up during Alumni his commit- week. Many store fronts are dressed tee have Alumni Day up with artifacts saluting the oldest had years active Alumni in the country. If you are of experi- Events an active part of the parade, you can ence in feel the vibes from the owners when putting this June 13, 2020 you pass by their business with the all togeth- er. Bob smiles and waves they return from the PARADE THEME: parade participants. It’s just great to S t r i n g e r, be a part of the atmosphere and worth sort of “Board Games” all the effort put into presenting this s e m i - retired member of this committee, still Tradition has it that the 25-year Starting Time: 10:30 a.m. wonderful traditional extravaganza by class has the privilege to select the those prideful Stevens Alumni mem- lends his expertise to a great bunch of volunteers. Carolyn LeBlanc contin- parade marshal. This year the class of bers who work endlessly to put the BUSINESS MEETING/LUNCHEON: ues her responsibility of contacting the 1994 chose Ray Bernard, SHS Soccer show together yearly. StevensEvent High School Cafeteria bands and other units such as the Coach for many years and Dave 2019’s parade theme challenged immediately following the parade Shriners and their mini-cars, as well as Stockwell, retired Chemistry teacher the class worker-bees to come up with speaking with agencies and securing at Stevens. -

Fast Times at Ridgemont High</I>

McNair Scholars Journal Volume 9 | Issue 1 Article 16 2005 Fast Times at Ridgemont High and Porky’s: Gender Perspective in the Teen Comedy Kerri VanderHoff Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair Recommended Citation VanderHoff, Kerri (2005) "Fast Times at Ridgemont High and Porky’s: Gender Perspective in the Teen Comedy," McNair Scholars Journal: Vol. 9: Iss. 1, Article 16. Available at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair/vol9/iss1/16 Copyright © 2005 by the authors. McNair Scholars Journal is reproduced electronically by ScholarWorks@GVSU. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ mcnair?utm_source=scholarworks.gvsu.edu%2Fmcnair%2Fvol9%2Fiss1%2F16&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages Fast Times at Ridgemont High and Porky’s: Gender perspective in the teen comedy Abstract Teenage boys fantasizing about This study examines gender representation teenage girls—a normal and common in teen comedy with an emphasis on occurrence in everyday life, no doubt two films from the genre. Fast Times at about it, and a common subject in Ridgemont High (1982) was directed movies as well. Consider the following by a woman, Amy Heckerling. Porky’s scenarios from two teen comedies: (1981) was directed by a man, Bob Clark. In Fast Times at Ridgemont High This research reveals the different ways (1982), one boy, Brad, who has just male and female directors portray teenage returned home from his fast food job, girls and encourages a re-evaluation of the peeks out the bathroom window. His values conveyed to young viewers when younger sister’s friend, Linda, dives into the perspective represented in Hollywood the backyard pool. -

United Reggae Magazine #7

MAGAZINE #14 - December 2011 INTERVIEW Ken Boothe Derajah Susan Cadogan I-Taweh Dax Lion King Spinna Records Tribute to Fattis Burrell - One Love Sound Festival - Jamaica Round Up C-Sharp Album Launch - Frankie Paul and Cocoa Tea in Paris King Jammy’s Dynasty - Reggae Grammy 2012 United Reggae Magazine #14 - December 2011 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? Now you can... In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views and videos online each month you can now enjoy a SUMMARY free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month. 1/ NEWS EDITORIAL by Erik Magni 2/ INTERVIEWS • Bob Harding from King Spinna Records 10 • I-Taweh 13 • Derajah 18 • Ken Boothe 22 • Dax Lion 24 • Susan Cadogan 26 3/ REVIEWS • Derajah - Paris Is Burning 29 • Dub Vision - Counter Attack 30 • Dial M For Murder - In Dub Style 31 • Gregory Isaacs - African Museum + Tads Collection Volume II 32 • The Album Cover Art of Studio One Records 33 Reggae lives on • Ashley - Land Of Dub 34 • Jimmy Cliff - Sacred Fire 35 • Return of the Rub-A-Dub Style 36 This year it has been five years since the inception of United Reggae. Our aim • Boom One Sound System - Japanese Translations In Dub 37 in 2007 was to promote reggae music and reggae culture. And this still stands. 4/ REPORTS During this period lots of things have happened – both in the world of reg- • Jamaica Round Up: November 2011 38 gae music and for United Reggae. Today United Reggae is one of the leading • C-Sharp Album Launch 40 global reggae magazines, and we’re covering our beloved music from the four • Ernest Ranglin and The Sidewalk Doctors at London’s Jazz Cafe 41 corners of the world – from Kingston to Sidney, from Warsaw to New York. -

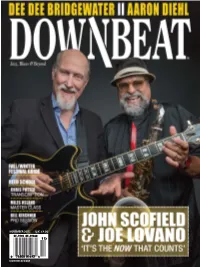

Downbeat.Com November 2015 U.K. £4.00

NOVEMBER 2015 2015 NOVEMBER U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT JOHN SCOFIELD « DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER « AARON DIEHL « ERIK FRIEDLANDER « FALL/WINTER FESTIVAL GUIDE NOVEMBER 2015 NOVEMBER 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall Editorial Intern Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; -

Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 3 American Pie Don Mclean 1972 4

AS VOTED AT OLDIESBOARD.COM 10/30/17 THROUGH 12/4/17 CONGRATULATIONS TO “HEY JUDE”, THE #1 SELECTION FOR THE 19 TH TIME IN 20 YEARS! Ti tle Artist Year 1 Hey Jude Beatles 1968 2 (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 3 American Pie Don McLean 1972 4 Light My Fire Doors 1967 5 In The Still Of The Nite Five Satins 1956 6 I Want To Hold Your Hand Beatles 1964 7 MacArthur Park Richard Harris 1968 8 Rag Doll Four Seasons 1964 9 God Only Knows Beach Boys 1966 10 Ain't No Mount ain High Enough Diana Ross 1970 11 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon and Garfunkel 1970 12 Because Dave Clark Five 1964 13 Good Vibrations Beach Boys 1966 14 Cherish Association 1966 15 She Loves You Beatles 1964 16 Hotel California Eagles 1977 17 St airway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 18 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 19 My Girl Temptations 1965 20 Let It Be Beatles 1970 21 Be My Baby Ronettes 1963 22 Downtown Petula Clark 1965 23 Since I Don't Have You Skyliners 1959 24 To Sir With Love Lul u 1967 25 Brandy (You're A Fine Girl) Looking Glass 1972 26 Suspicious Minds Elvis Presley 1969 27 You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' Righteous Brothers 1965 28 You Really Got Me Kinks 19 64 29 Wichita Lineman Glen Campbell 1968 30 The Rain The Park & Ot her Things Cowsills 1967 31 A Hard Day's Night Beatles 1964 32 A Day In The Life Beatles 1967 33 Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 34 Imagine John Lennon 1971 35 I Only Have Eyes For You Flamingos 1959 36 Waterloo Sunset Kinks 1967 37 Bohemian Rhapsody Queen 76 -92 38 Sugar Sugar Archies 1969 39 What's -

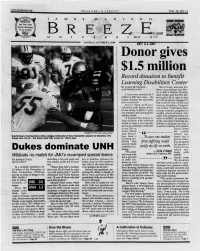

October 2, 2000

"Knowledge is Liberty VOL. 78, NO. 11 M M A N DOW JONES R Z E ^ I Hhf,T Y -—HM1MS MONDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2000 Tscnrnmr Donor gives $1.5 million Record donation to benefit Learning Disabilities Center BY ALISON ROTHSCHILD Steve Evans, associate pro- contributing writer fessor of psychology and direc- tor of JMU's Human Develop- A local man donated $1.5 ment Center, said that this gen- million to JMU last week — the erous gift will be used to sup- largest donation the university port the programs designed to has ever received. help students with ADHD and Alvin V. Baird, an 83-year- learning disabilities. Programs old retired cattle farmer, donat- will include Challenging Hori- ed the money to JMU's 1-year- zons,an outreach program for old Attention and Learning Dis- middle school students who abilities Center. suffer from attention deficit dis- "I donated this money to order or ADHD, an expansion help children with ailments of the university's learning dis- similar to mine, to save one stu- abilities evaluation services, a dent from suffering would justi- remedial reading and mathe- fy my life on matics center earth," Baird for public ROBERT NATT/ttfu'or photographer said. He suf- -a school stu- Quarterback Charles Berry (#11) dodges University of New Hampshire players on Saturday. The fers from a ... To save one student dents and a Dukes won 24-13. "We knew what they could do," Berry said. learning dis- parent train- ability that from suffering would ing program severely limits for parents of analytical rea- justify my life on earth.