Analysis of the Economic Impact of Constructing a NBA Arena on the Host City Grant Gilchrist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Probable Starters

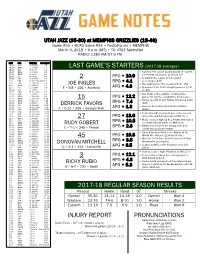

UTAH JAZZ (35-30) at MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES (18-46) Game #66 • ROAD Game #34 • FedExForum • MEMPHIS March 9, 2018 • 6 p.m. (MT) • TV: AT&T SportsNet RADIO: 1280 AM/97.5 FM DATE OPP. TIME (MT) RECORD/TV 10/18 DEN W, 106-96 1-0 10/20 @MIN L, 97-100 1-1 LAST GAME’S STARTERS (2017-18 averages) 10/21 OKC W, 96-87 2-1 10/24 @LAC L, 84-102 2-2 • Notched first career double-double (11 points, 10/25 @PHX L, 88-97 2-3 career-high 10 assists) at IND on 3/7 10/28 LAL W, 96-81 3-3 PPG • 10.9 10/30 DAL W, 104-89 4-3 2 • Second in the league in three-point 11/1 POR W, 112-103 (OT) 5-3 RPG • 4.1 percentage (.445) 11/3 TOR L, 100-109 5-4 JOE INGLES • Has eight games this season with 5+ 3FG 11/5 @HOU L, 110-137 5-5 11/7 PHI L, 97-104 5-6 F • 6-8 • 226 • Australia APG • 4.3 • Appeared in his 200th straight game on 2/24 11/10 MIA L, 74-84 5-7 vs. DAL 11/11 BKN W, 114-106 6-7 11/13 MIN L, 98-109 6-8 • Has made a three-pointer in consecutive 11/15 @NYK L, 101-106 6-9 PPG • 12.2 games for just the second time in his career 11/17 @BKN L, 107-118 6-10 15 11/18 @ORL W, 125-85 7-10 RPG • 7.4 • Ranks seventh in Jazz history in blocked shots 11/20 @PHI L, 86-107 7-11 DERRICK FAVORS (641) 11/22 CHI W, 110-80 8-11 Jazz are 11-3 when he records a double- 11/25 MIL W, 121-108 9-11 • APG • 1.3 11/28 DEN W, 106-77 10-11 F • 6-10 • 265 • Georgia Tech double 11/30 @LAC W, 126-107 11-11 st 12/1 NOP W, 114-108 12-11 • Posted his 21 double-double of the season 12/4 WAS W, 116-69 13-11 27 PPG • 13.6 (23 points and 14 rebounds) at IND (3/7) 12/5 @OKC L, 94-100 13-12 • Made a career-high 12 free throws and scored 12/7 HOU L, 101-112 13-13 RPG • 10.5 12/9 @MIL L, 100-117 13-14 RUDY GOBERT a season-high 26 points vs. -

Jay-Z Adds Second Brooklyn Show to the 4:44 Tour Due to Overwhelming Demand

JAY-Z ADDS SECOND BROOKLYN SHOW TO THE 4:44 TOUR DUE TO OVERWHELMING DEMAND WHO: JAY-Z WHAT: Additional Brooklyn date for the 4:44 TOUR WHEN: November 27th, 2017 HOW: Continuing its commitment to bring fans closer to their favorite artists, TIDAL members will have access to a special presale beginning on Tuesday, July 11th at 12pm ET. Members can find details for purchasing tickets at Sprint.TIDAL.com. Citi® is the official presale credit card for the 4:44 TOUR. As such, Citi® cardmembers will have access to purchase U.S. presale tickets beginning Tuesday, July 11th at 12pm ET until Thursday, July 13th at 10:00pm ET through Citi’s Private Pass® program. For complete presale details visit www.citiprivatepass.com. Tickets for the 4:44 TOUR go on sale to the general public starting Friday, July 14th at 10am local time at livenation.com. VIP Packages are available at VIPNation.com. WHERE: See below dates. 4:44 TOUR ITINERARY Friday, October 27 Anaheim, CA Honda Center Saturday, October 28 Las Vegas, NV T-Mobile Arena Wednesday, November 1 Fresno, CA Save Mart Center at Fresno State Friday, November 3 Phoenix, AZ Talking Stick Resort Arena Sunday, November 5 Denver, CO Pepsi Center Arena Tuesday, November 7 Dallas, TX American Airlines Center Wednesday, November 8 Houston, TX Toyota Center Thursday, November 9 New Orleans, LA Smoothie King Center Saturday, November 11 Orlando, FL Amway Center Sunday, November 12 Miami, FL American Airlines Arena Tuesday, November 14 Atlanta, GA Philips Arena Wednesday, November 15 Nashville, TN Bridgestone -

The Main Chapel of the Durres Amphitheater Decoration and Chronology1

SPIOX - B1: MFA092 - cap. 13 - (1ª bozza) MEFRA – 121/2 – 2009, p. 569-595. The main chapel of the Durres amphitheater Decoration and chronology1 Kim BOWES and John MITCHELL The amphitheater at Durres in central Albania series of limited excavations to clarify the is one of the larger and better preserved building’s post-Roman and Byzantine chronology, amphitheaters of the Roman world, as well as one we completed an in-depth study of the mosaic of the eastern-most examples of the amphitheater chapel, its structure and decoration (fig. 1). form. Nonetheless, it is not for its Roman architecture that the building is best known, but ANCIENT DYRRACHIUM AND ITS AMPHITHEATER its later Christian decoration, specifically, a series of mosaics which adorn the walls of a small chapel Named Epidamnos by its Greek founders and inserted into the amphitheater’s Roman fabric. Dyrrachium by the Romans, Durres was the First published by Vangel Toçi in 1971, these principal city of Epirus Vetus and the land mosaics were introduced to a wider scholarly terminus of the Via Egnatia, the road that audience through their inclusion in Robin throughout late antiquity and the Byzantine Cormack’s groundbreaking 1985 volume Writing period linked Rome to Constantinople.3 Durres in Gold.2 Despite the mosaics general renowned, also sat on a major Adriatic trade route linking the however, they have been studied largely as northern Greek Islands to Dalmatia and northern membra disjecta, cut off from their surrounding Italy. Thus, like Marseilles or Thessaloniki, Durres context, both architectural and decorative. was a place where road met sea and the cultural 6In 2002 and 2003, the authors and a team of currents of east and west mingled. -

Sacramento Kings Choose Comcast Business to Deliver Enhanced Fan Experience at New Indoor Sports and Entertainment Venue

SACRAMENTO KINGS CHOOSE COMCAST BUSINESS TO DELIVER ENHANCED FAN EXPERIENCE AT NEW INDOOR SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT VENUE Professional Basketball Team to Leverage Gigabit Ethernet Services at Golden 1 Center, Plaza, and Downtown Commons SACRAMENTO KINGS MOVE TO NEW, TECHNOLOGICALLY ADVANCED SITUATION SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT COMPLEX • Professional The Sacramento Kings are an American professional basketball team based in basketball team • Moving to new sports & Northern California. The Kings are one of the oldest continually operating professional entertainment venue basketball franchises in the nation, and the oldest in professional basketball. The Kings have played in Sacramento’s Sleep Train Arena (formerly ARCO Arena CHALLENGE II) since 1988. Ahead of the ’16-’17 season, the team will move to a new, world-class • Needed scalable capacity sports and entertainment venue, called Golden 1 Center, that will feature cutting-edge to provide WiFi access for technology designed to enhance how fans interact with the team. The publicly-owned fans, team management venue will open in October 2016, and will be a key attraction in a newly constructed and surrounding business business and entertainment district called Downtown Commons (DOCO). and entertainment district • Wanted bandwidth for uploads to television monitors throughout SIGNIFICANT BANDWIDTH CAPACITY NECESSARY TO DELIVER stadium ULTIMATE FAN EXPERIENCE When building its new indoor arena, the Kings sought to deploy a back-end SOLUTION infrastructure that would support the back-end technology -

A New Model to Modernize U.S. Infrastructure

Bridging the Gap Together: A New Model to Modernize U.S. Infrastructure May 2016 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS BPC staff produced this report in collaboration with a distinguished group of senior advisors and experts. BPC would like to thank Aaron Klein, Fellow, Economic Studies and Policy Director, Initiative on Business and Public Policy, the Brookings Institution, and the council’s staff for their contributions and continued support. In addition, BPC thanks all the organizations and individuals who participated in the research and contributed to the council’s roundtables and regional forums for their feedback. EXECUTIVE COUNCIL ON INFRASTRUCTURE 7KH([HFXWLYH&RXQFLORQ,QIUDVWUXFWXUHLVDZRUNLQJJURXSRIFRUSRUDWH&(2VDQGH[HFXWLYHVGUDZQIURPWKHÀQDQFLDOLQGXVWULDO logistics, and services industries. The council has developed recommendations to help facilitate increased private sector investment in U.S. infrastructure. DISCLAIMER This report is a product of the BPC Executive Council on Infrastructure, whose membership includes executives of diverse RUJDQL]DWLRQV7KHFRXQFLOUHDFKHGFRQVHQVXVRQWKHVHUHFRPPHQGDWLRQVDVDSDFNDJH7KHÀQGLQJVDQGUHFRPPHQGDWLRQV expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of the council member companies, the members of the Political Advisory Group, the Bipartisan Policy Center’s founders or its board of directors. 1 Executive Council on Infrastructure Doug Peterson President and CEO, S&P Global Co-Chair, Executive Council on Infrastructure Susan Story President and CEO, American Water Co-Chair, Executive Council on Infrastructure Eric Cantor Vice Chairman and Managing Director, Moelis & Co. Former House Majority Leader Patrick Decker President and CEO, Xylem Inc. Michael Ducker President and CEO, FedEx Freight Jack Ehnes &KLHI([HFXWLYH2IÀFHU&DOLIRUQLD6WDWH7HDFKHUV· Retirement System (CalSTRS) Jane Garvey Chairman of North America, Meridiam P. Scott Ozanus Deputy Chairman and COO, KPMG Suzanne Shank Chairman and CEO, Siebert Brandford Shank & Co., LLC 2 Political Advisory Group Haley Barbour Former Governor Steve Bartlett Former U.S. -

Schedule/Results 2019-20 Men's Basketball

2019-20 MEN’S BASKETBALL Game 9 OPENING TIP Pac-12 week will continue for UC Davis on Friday SCHEDULE/RESULTS when it visits the Jon M. Huntsman Center for a Overall: 2-6 Big West: 0-0 non-conference matchup against the Utah Utes. Home: 1-0 Road: 0-4 Neutral: 1-2 Tipoff from Salt Lake City is set for 6 p.m. PT/7 p.m. MT. Nov. 5 at Loyola Chicago ............................... L, 82-48 UC DAVIS AGGIES (2-6) Nov. 7 William Jessup.......................... W, 109-63 at Calling the Pac-12 Networks broadcast that Nov. 14 vs. Idaho2 ........................................ W, 65-64 UTAH UTES (4-2) evening are JB Long and Don Maclean. Sports Nov. 15 at Arkansas State2 .............................L, 80-67 1140 KHTK will provide Scott Marsh’s call; fans Nov. 17 vs. VMI2 ...................................L, 89-84 (2OT) • can also access his broadcast on TuneIn Radio November 29, 2019 6 p.m. PT/7 p.m. MT Nov. 20 vs. Sacramento State1 ........................L, 61-51 Jon M. Huntsman Center (15,000) - Salt Lake City through the station’s page (search Sports 1140 Nov. 23 at Portland ....................................... L, 62-52 TV: Pac-12 Networks KHTK). Links for a video stream (available for Pac- Radio: Sports 1140 KHTK 12 Networks subscribers only), internet audio, live Nov. 26 at Cal (Pac-12 Networks) ...................L, 72-66 Online Stream: Pac-12.com stats and in-game Twitter updates are available Nov. 29 at Utah (Pac-12 Networks).... 6 p.m. PT/7 p.m. MT Internet Audio: TuneIn Radio online at Gameday Central. -

Eric Church Doesn't Back Down on Holdin' My Own

ERIC CHURCH DOESN’T BACK DOWN ON HOLDIN’ MY OWN TOUR Standing behind his vow to put face-value tickets in fans’ hands, Church cancels secondary market ticket orders and releases them back to the public - Tuesday, Feb 21 at NOON. Tickets available while supplies last for Eric’s show at STAPLES Center in Los Angeles on March 31 at www.AXS.com. Nashville, Tenn. – After witnessing the three-hour, two-set marathon show at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center merely weeks ago, Rolling Stone professed, “Eric Church sets the bar.” The exchange in energy with the audience and passion that fuels the man behind the CMA’s Album of the Year is an earned one after years of putting his fans first. Whether it is the dozens in attendance at his first performance in Bethel, New York or the 15,842 in attendance for last month’s breezy night in Brooklyn, it is that unrivaled dedication to surpassing their expectations that is driving another mission: ensuring fans’ hard-earned money is spent fairly on face-value tickets at each and every stop on his 60-plus city Holdin’ My Own Tour. Throughout the Holdin’ My Own Tour, Eric and his team have systematically identified, cancelled and released tickets back to the public that were identified as scalper tickets. Already on the tour, Eric’s management team used a proprietary program to release thousands of tickets back to the public and fans in markets like Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Toronto, Vancouver and Boston. On Feb. 21 at noon local time, the team will release to the official ticketing website all tickets identified as scalper-purchased for the remaining markets back to the public. -

Transport Infrastructure Development Performance

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia Engineering 178 ( 2017 ) 319 – 329 16th Conference on Reliability and Statistics in Transportation and Communication, RelStat’2016, 19-22 October, 2016, Riga, Latvia Transport Infrastructure Development Performance Oksana Skorobogatova, Irina Kuzmina-Merlino* Transport and Telecommunication Institute, 1 Lomonosova str., Riga, LV-1019, Latvia Abstract Transport infrastructure is an integral part of the transport system of any city or state. In connection with the development of society and intensification of international relations due to the globalization processes, the importance of transport as a factor for economic and social development has enhanced. Various aspects of the activities related to the development of transport infrastructure have increasingly become the objects of scientific researches. Transportation as an economic factor is a measure of economic activity and at the same time transportation is a reflection of economic activity. So, the questions about transport infrastructure performance measurement and relationship between transport infrastructure and economic growth are the subjects for discussions in both academic and non-academic circles. This paper highlights the role of the transportation industry in economic development of Latvia, describes the concept of transport infrastructure as an important part of the state transport system, and estimates the employed international approaches to the measurement of performance of transport infrastructure development. The article focuses on the necessity for the development of the methodology of measuring the transport infrastructure performance, that should be applied systematically and that would be generally helpful to all responsible people making transportation-related decisions. © 20172017 The The Authors. Authors. Published Published by Elsevierby Elsevier Ltd. -

Canal Side Design Guidelines

Canal Side Design Guidelines Issued by: Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation A subsidiary of the New York State Urban Development Corporation d/b/a Empire State Development Corporation 95 Perry Street- Suite 500 Buffalo, NY 14203-3030 Prepared by: Ehrenkrantz, Eckstut & Kuhn Architects July, 2009 revised March, 2010 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Use 5 3. Massing 8 4. Circulation 12 5. Architectural Features 16 6. Materials 23 7. Signage 25 8. Lighting 26 9. Erie Canal Harbor Parcels 27 10. Sustainability 28 11. Design Review Process 33 Appendix 36 Sections 3.3 & 3.5 of the 2005 Erie Canal Harbor Amendment to the Urban Renewal Plan for the Waterfront Redevelopment Project 1. Introduction Canal Side (the “Project”) is a new mixed-use neighborhood that will reconnect Downtown Buffalo to the Lake Erie waterfront through a network of streets, canals, and public spaces, evoking the City’s history, while creating a timeless neighborhood that will help defi ne its future. With approximately 1.1 million square feet of development, including retail, restaurant, hotel, offi ce, cultural, and residential uses, Canal Side is made up of 23 development parcels within approximately 20 acres on the Buffalo Riverfront (“Project Area”). Anchored by a destination retailer, the Project offers urban amenities and year-round offerings and experiences, including restaurants, entertainment venues, retail outlets, cultural attractions, public spaces, and increased access to the Buffalo River. The proposed Canal Side Site Plan (“Site Plan”, see Exhibit 1) identifi es the conceptual design for the mixed-use project. These Canal Side Design Guidelines (“Guidelines”) apply to all development parcels within Canal Side. -

Why Is Infrastructure Important? 23

Why Is Infrastructure David Alan Aschauer* As the decade of the 1990s begins, new challenges present them- selves to the citizenry of the United States. Among the most important are concerns about the environment, economic productivity, and inter- national competitiveness, and a rearrangement of standing strategic military relationships. Our future quality of life, economic prosperity, and security depend crucially on how we choose to meet these new challenges. The apparent failure of the communist economic system and the associated relaxation of Cold War tensions offer the potential for a significant reallocation of the nation’s resources from military to other uses. A crucial question then arises whether these resources should be channeled to the private sector, effecting overall government expendi- ture reduction, or kept within the public sector, thereby inducing an alteration in the composition of government spending. The first direction, expenditure reduction, certainly has merit to a broad class of individuals. Many would point to the fact that total federal government outlays, expressed relative to gross national product, rose from 14.8 percent in 1950 to 21.6 percent in 1980 and, in 1989, to 21.8 percent. Others would point to the persistence of federal budget deficits. To both groups, expenditure reduction would be of benefit to economic performance, either by reducing the overall scale of govern- ment activity in the economy or by allowing a reduction in interest rates and an expansion in domestic investment activity. *Formerly Senior Economist, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, and now Elmer W. Campbell Professor of Economics, Bates College. 22 David Alan Aschauer But the second direction, expenditure reorientation, may also have merit. -

Opponents Nba Directory Nba Directory Eiw Eod History Records 16-17 Review Players Leadership

OPPONENTS NBA DIRECTORY NBA DIRECTORY LEADERSHIP PLAYERS 16-17 NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION CANADA NBA ENTERTAINMENT 50 Bay Street, Suite 1402, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5J 3A5 WOMEN’S NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCATION Telephone: . (416) 682-2000 Fax: ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� (416) 364-0205 NBA G LEAGUE NEW YORK ASIA/PACIFIC Olympic Tower, 645 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10022 Telephone: ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� (212) 407-8000 HONG KONG REVIEW RECORDS HISTORY Fax: �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������(212) 832-3861 Room 3101, Lee Gardens One, 33 Hysan Avenue, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong Telephone: . .+852-2843-9600 NEW JERSEY Fax: �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� +852-2536-4808 100 Plaza Drive, Secaucus, NJ 07094 Telephone: ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� (201) 865-1500 TAIWAN Fax: �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������(201) 974-5973 Suite 1303, No. 88, Section 2, Chung Hsiao East Road, Taipei, Taiwan ROC 100 Telephone: -

Schedule/Results 2018-19 Men's Basketball

2018-19 MEN’S BASKETBALL Game 28 OPENING TIP A season-ending four-game homestand will SCHEDULE/RESULTS continue on Saturday when UC Davis hosts Cal Overall: 10-17 Big West: 6-7 State Fullerton in a Big West contest that will begin Home: 6-4 Road: 3-12 Neutral: 1-1 at 7 p.m. In this matchup, the Aggies will look to bounce back from Thursday night’s result against Nov. 6 San Francisco ..............................L, 76-42 CAL STATE FULLERTON TITANS a TItan team they faced last week. Nov. 9 San Diego .................................... L, 76-57 (14-14, 10-4) Nov. 12 at Arkansas 2 ..................................... L, 81-58 at In last week’s game at Titan Gym, senior guard Siler Nov. 17 vs. Texas A&M Corpus Christi 2 W, 54-57 (OT) Schneider scored a season-high 27 points on 11 of Nov. 18 at UT Arlington 2 .............................. L, 68-59 UC DAVIS AGGIES (10-17, 6-7) 15 shooting, junior guard Stefan Gonzalez recorded Nov. 20 vs. Sacramento State 1 ..................... L, 58-55 10 points, which included two baskets from three, March 2, 2019 • 7 p.m. 2 and junior guard Joe Mooney led everyone that Nov. 23 at Indiana .......................................L, 76-62 The Pavilion (5,931) - Davis, Calif. night with nine rebounds in a game that went down Nov. 29 Northern Arizona ........................ W, 73-57 to the wire. Video: BigWest.TV Radio: Sports 1140 KHTK Dec. 5 at Northern Illinois ............................ L, 71-62 That evening, eight lead changes took place Internet Audio: TuneIn Radio (Search: KHTK) Dec.