Meeting an Expanding Human Population's Needs Whilst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommended Trees for Winnetka

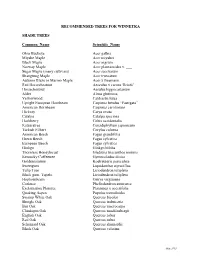

RECOMMENDED TREES FOR WINNETKA SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Ohio Buckeye Acer galbra Miyabe Maple Acer miyabei Black Maple Acer nigrum Norway Maple Acer plantanoides v. ___ Sugar Maple (many cultivars) Acer saccharum Shangtung Maple Acer truncatum Autumn Blaze or Marmo Maple Acer x freemanii Red Horsechestnut Aesculus x carnea 'Briotii' Horsechestnut Aesulus hippocastanum Alder Alnus glutinosa Yellowwood Caldrastis lutea Upright European Hornbeam Carpinus betulus “Fastigata” American Hornbeam Carpinus carolinians Hickory Carya ovata Catalpa Catalpa speciosa Hackberry Celtis occidentalis Katsuratree Cercidiphyllum japonicum Turkish Filbert Corylus colurna American Beech Fagus grandifolia Green Beech Fagus sylvatica European Beech Fagus sylvatica Ginkgo Ginkgo biloba Thornless Honeylocust Gleditsia triacanthos inermis Kentucky Coffeetree Gymnocladus dioica Goldenraintree Koelreuteria paniculata Sweetgum Liquidambar styraciflua Tulip Tree Liriodendron tulipfera Black gum, Tupelo Liriodendron tulipfera Hophornbeam Ostrya virginiana Corktree Phellodendron amurense Exclamation Plantree Plantanus x aceerifolia Quaking Aspen Populus tremuloides Swamp White Oak Quercus bicolor Shingle Oak Quercus imbricaria Bur Oak Quercus macrocarpa Chinkapin Oak Quercus muehlenbergii English Oak Quercus robur Red Oak Quercus rubra Schumard Oak Quercus shumardii Black Oak Quercus velutina May 2015 SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Sassafras Sassafras albidum American Linden Tilia Americana Littleleaf Linden (many cultivars) Tilia cordata Silver -

Approved Plant List 10/04/12

FLORIDA The best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago, the second best time to plant a tree is today. City of Sunrise Approved Plant List 10/04/12 Appendix A 10/4/12 APPROVED PLANT LIST FOR SINGLE FAMILY HOMES SG xx Slow Growing “xx” = minimum height in Small Mature tree height of less than 20 feet at time of planting feet OH Trees adjacent to overhead power lines Medium Mature tree height of between 21 – 40 feet U Trees within Utility Easements Large Mature tree height greater than 41 N Not acceptable for use as a replacement feet * Native Florida Species Varies Mature tree height depends on variety Mature size information based on Betrock’s Florida Landscape Plants Published 2001 GROUP “A” TREES Common Name Botanical Name Uses Mature Tree Size Avocado Persea Americana L Bahama Strongbark Bourreria orata * U, SG 6 S Bald Cypress Taxodium distichum * L Black Olive Shady Bucida buceras ‘Shady Lady’ L Lady Black Olive Bucida buceras L Brazil Beautyleaf Calophyllum brasiliense L Blolly Guapira discolor* M Bridalveil Tree Caesalpinia granadillo M Bulnesia Bulnesia arboria M Cinnecord Acacia choriophylla * U, SG 6 S Group ‘A’ Plant List for Single Family Homes Common Name Botanical Name Uses Mature Tree Size Citrus: Lemon, Citrus spp. OH S (except orange, Lime ect. Grapefruit) Citrus: Grapefruit Citrus paradisi M Trees Copperpod Peltophorum pterocarpum L Fiddlewood Citharexylum fruticosum * U, SG 8 S Floss Silk Tree Chorisia speciosa L Golden – Shower Cassia fistula L Green Buttonwood Conocarpus erectus * L Gumbo Limbo Bursera simaruba * L -

Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity of the Leaves, Bark and Stems of Liquidambar Styraciflua L

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2016) 5(1): 306-317 ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 5 Number 1(2016) pp. 306-317 Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article http://dx.doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2016.501.029 Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity of the Leaves, Bark and Stems of Liquidambar styraciflua L. (Altingiaceae) Graziele Francine Franco Mancarz1*, Ana Carolina Pareja Lobo1, Mariah Brandalise Baril1, Francisco de Assis Franco2 and Tomoe Nakashima1 1Pharmaceutical ScienceDepartment, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brazil 2Coodetec Desenvolvimento, Produção e Comercialização Agrícola Ltda, Cascavel, PR, Brazil *Corresponding author A B S T R A C T K e y w o r d s The genus Liquidambar L. is the best-known genus of the Altingiaceae Horan family, and species of this genus have long been used for the Liquidambar treatment of various diseases. Liquidambar styraciflua L., which is styraciflua, popularly known as sweet gum or alligator tree, is an aromatic deciduous antioxidant tree with leaves with 5-7 acute lobes and branched stems. In the present activity, study, we investigated the antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of aerial antimicrobial parts of L.styraciflua. Antimicrobial activity was evaluated using the activity, microdilution methodology. The DPPH and phosphomolybdenum methods microdilution method, were used to assess the antioxidant capacity of the samples. The extracts DPPH assay showed moderate or weak antimicrobial activity. The essential oil had the lowest MIC values and exhibited bactericidal action against Escherichia Article Info coli, Enterobacter aerogenes and Staphylococcus aureus. The ethyl acetate fraction and the butanol fraction from the bark and stem showed the best Accepted: antioxidant activity. -

Environmental Weeds, Adelaide Region

Sustainable Landscapes Project Interim integrated weed list for the greater Adelaide region incorporating: • Weeds of National Significance • SA Urban Forest Biodiversity Program environmental weed list • CRC for Australian Weed Management factsheet: Alternatives to invasive garden plants, Greater Adelaide Region 2004 • CSIRO ten most serious invasive garden plants for sale in South Australia # Many of the plants in the following list may not cause problems if properly contained, but when planted or dumped near remant native vegetation can easily escape and become invasive. We recommend that these plants only be planted in areas where they do not cause problems, and even then that they be carefully maintained and monitored. Plant species common as environmental weeds of the Adelaide region * non-native (exotic) species ** proclaimed species # CSIRO invasive Trees and tall shrubs Common name Scientific name Where it is a problem Cootamundra wattle Acacia baileyana hills silver wattle Acacia dealbata hills early black wattle Acacia decurrens hills Flinders Ranges wattle Acacia iteaphylla Acacia longifolia var. hills sallow wattle longifolia # golden wreath wattle Acacia saligna all areas tree of heaven *Ailanthus altissima plains, hills Irish strawberry tree *Arbutus unedo hills tree lucerne / tagasaste *Chamaecytisus palmensis plains, hills, creek cotoneaster *Cotoneaster spp. creek, hills May hawthorn *Crataegus monogyna creek, hills ** azzarola Crataegus sinaica creek, hills *Fraxinus angustifolia ssp. creek, hills # desert ash oxycarpa pincushion hakea Hakea laurina hills tree tobacco *Nicotiana glauca all areas ** # olive *Olea europaea all areas (Olives can be grown for agricultural purposes) Cape Leeuwin wattle Paraserianthes lophantha creek, hills, coast ** # Aleppo pine *Pinus halepensis plains, hills,mallee radiata pine *Pinus radiata hills sweet pittosporum Pittosporum undulatum plains, hills, creek myrtle-leaf milkwort *Polygala myrtifolia hills, coast poplar *Populus spp. -

United States Department of Agriculture

Pest Management Science Pest Manag Sci 59:788–800 (online: 2003) DOI: 10.1002/ps.721 United States Department of Agriculture—Agriculture Research Service research on targeted management of the Formosan subterranean termite Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae)†‡ Alan R Lax∗ and Weste LA Osbrink USDA-ARS-Southern Regional Research Center, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA Abstract: The Formosan subterranean termite, Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki is currently one of the most destructive pests in the USA. It is estimated to cost consumers over US $1 billion annually for preventative and remedial treatment and to repair damage caused by this insect. The mission of the Formosan Subterranean Termite Research Unit of the Agricultural Research Service is to demonstrate the most effective existing termite management technologies, integrate them into effective management systems, and provide fundamental problem-solving research for long-term, safe, effective and environmentally friendly new technologies. This article describes the epidemiology of the pest and highlights the research accomplished by the Agricultural Research Service on area-wide management of the termite and fundamental research on its biology that might provide the basis for future management technologies. Fundamental areas that are receiving attention are termite detection, termite colony development, nutrition and foraging, and the search for biological control agents. Other fertile areas include understanding termite symbionts that may provide an additional target for control. Area-wide management of the termite by using population suppression rather than protection of individual structures has been successful; however, much remains to be done to provide long-term sustainable population control. An educational component of the program has provided reliable information to homeowners and pest-control operators that should help slow the spread of this organism and allow rapid intervention in those areas which it infests. -

Tree of the Year: Liquidambar Eric Hsu and Susyn Andrews

Tree of the Year: Liquidambar Eric Hsu and Susyn Andrews With contributions from Anne Boscawen (UK), John Bulmer (UK), Koen Camelbeke (Belgium), John Gammon (UK), Hugh Glen (South Africa), Philippe de Spoelberch (Belgium), Dick van Hoey Smith (The Netherlands), Robert Vernon (UK) and Ulrich Würth (Germany). Affinities, generic distribution and fossil record Liquidambar L. has close taxonomic affinities with Altingia Noronha since these two genera share gum ducts associated with vascular bundles, terminal buds enclosed within numerous bud scales, spirally arranged stipulate leaves, poly- porate (with several pore-like apertures) pollen grains, condensed bisexual inflorescences, perfect or imperfect flowers, and winged seeds. Not surpris- ingly, Liquidambar, Altingia and Semiliquidambar H.T. Chang have now been placed in the Altingiaceae, as originally treated (Blume 1828, Wilson 1905, Chang 1964, Melikan 1973, Li et al. 1988, Zhou & Jiang 1990, Wang 1992, Qui et al. 1998, APG 1998, Judd et al. 1999, Shi et al. 2001 and V. Savolainen pers. comm.). These three genera were placed in the subfamily Altingioideae in Hamamelidaceae (Reinsch 1890, Chang 1979, Cronquist 1981, Bogle 1986, Endress 1989) or the Liquidambaroideae (Harms 1930). Shi et al. (2001) noted that Altingia species are evergreen with entire, unlobed leaves; Liquidambar is deciduous with 3-5 or 7-lobed leaves; while Semiliquidambar is evergreen or deciduous, with trilobed, simple or one-lobed leaves. Cytological studies have indicated that the chromosome number of Liquidambar is 2n = 30, 32 (Anderson & Sax 1935, Pizzolongo 1958, Santamour 1972, Goldblatt & Endress 1977). Ferguson (1989) stated that this chromosome number distinguished Liquidambar from the rest of the Hamamelidaceae with their chromosome numbers of 2n = 16, 24, 36, 48, 64 and 72. -

7008 Australian Native Plants Society Australia Hakea

FEBRUARY 20 10 ISSN0727 - 7008 AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS SOCIETY AUSTRALIA HAKEA STUDY GROUP NEWSLETTER NUMBER 42 Leader: Paul Kennedy PO Box 220 Strathmerton,Vic. 3 64 1 e mail: hakeaholic@,mpt.net.au Dear members. The last week of February is drawing to a close here at Strathrnerton and for once the summer season has been wetter and not so hot. We have had one very hot spell where the temperature reached the low forties in January but otherwise the maximum daily temperature has been around 35 degrees C. The good news is that we had 25mm of rain on new years day and a further 60mm early in February which has transformed the dry native grasses into a sea of green. The native plants have responded to the moisture by shedding that appearance of drooping lack lustre leaves to one of bright shiny leaves and even new growth in some cases. Many inland parts of Queensland and NSW have received flooding rains and hopefully this is the signal that the long drought is finally coming to an end. To see the Darling River in flood and the billabongs full of water will enable regeneration of plants, and enable birds and fish to multiply. Unfortunately the upper reaches of the Murray and Murrurnbidgee river systems have missed out on these flooding rains. Cliff Wallis from Merimbula has sent me an updated report on the progress of his Hakea collection and was complaining about the dry conditions. Recently they had about 250mm over a couple of days, so I hope the species from dryer areas are not sitting in waterlogged soil. -

Environmental and Anthropogenic Impacts on Avifaunal Assemblages in an Urban Parkland, 1976 to 2007

Animals 2014, 4, 119-130; doi:10.3390/ani4010119 OPEN ACCESS animals ISSN 2076-2615 www.mdpi.com/journal/animals Article Environmental and Anthropogenic Impacts on Avifaunal Assemblages in an Urban Parkland, 1976 to 2007 Sara Elizabeth Ormond 1,†, Robert Whatmough 2, Irene Lena Hudson 3,‡ and Christopher Brian Daniels 4,* 1 School of Natural and Built Environments, University of South Australia, Mawson Lakes Campus, P.O. Box 2471, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia 2 11 Wakefield, St Kent Town, SA 5067, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of South Australia, Mawson Lakes Campus, P.O. Box 2471, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia 4 Barbara Hardy Institute, University of South Australia, Mawson Lakes Campus, P.O. Box 2471, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia † Present Address: Department for Environment, Water and Natural Resources, 2/17 Lennon Street, Clare, SA 5453, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected]. ‡ Present Address: School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, University of Newcastle, University Drive, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected]. * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-8-8302-2317; Fax: +61-8-8302-5613. Received: 11 December 2013; in revised form: 10 March 2014 / Accepted: 12 March 2014 / Published: 17 March 2014 Simple Summary: Over 32 years, the bird species assemblage in the parklands of Adelaide showed a uniform decline. Surprisingly, both introduced and native species declined, suggesting that even urban exploiters are affected by changes in the structure of cities. Climate and anthropogenic factors also cause short term changes in the species mix. -

Towards Resolving Lamiales Relationships

Schäferhoff et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2010, 10:352 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/10/352 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Towards resolving Lamiales relationships: insights from rapidly evolving chloroplast sequences Bastian Schäferhoff1*, Andreas Fleischmann2, Eberhard Fischer3, Dirk C Albach4, Thomas Borsch5, Günther Heubl2, Kai F Müller1 Abstract Background: In the large angiosperm order Lamiales, a diverse array of highly specialized life strategies such as carnivory, parasitism, epiphytism, and desiccation tolerance occur, and some lineages possess drastically accelerated DNA substitutional rates or miniaturized genomes. However, understanding the evolution of these phenomena in the order, and clarifying borders of and relationships among lamialean families, has been hindered by largely unresolved trees in the past. Results: Our analysis of the rapidly evolving trnK/matK, trnL-F and rps16 chloroplast regions enabled us to infer more precise phylogenetic hypotheses for the Lamiales. Relationships among the nine first-branching families in the Lamiales tree are now resolved with very strong support. Subsequent to Plocospermataceae, a clade consisting of Carlemanniaceae plus Oleaceae branches, followed by Tetrachondraceae and a newly inferred clade composed of Gesneriaceae plus Calceolariaceae, which is also supported by morphological characters. Plantaginaceae (incl. Gratioleae) and Scrophulariaceae are well separated in the backbone grade; Lamiaceae and Verbenaceae appear in distant clades, while the recently described Linderniaceae are confirmed to be monophyletic and in an isolated position. Conclusions: Confidence about deep nodes of the Lamiales tree is an important step towards understanding the evolutionary diversification of a major clade of flowering plants. The degree of resolution obtained here now provides a first opportunity to discuss the evolution of morphological and biochemical traits in Lamiales. -

Liquidambar Styraciflua L.) from Caroline County, Virginia

43 Banisteria, Number 9, 1997 © 1997 by the Virginia Natural History Society An Abnormal Variant of Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua L.) from Caroline County, Virginia Bruce L. King Department of Biology Randolph Macon College Ashland, Virginia 23005 Leaves of individuals of Liquidambar styraciflua L. Similar measurements were made from surrounding (sweetgum) - are predominantly 5-lobed, occasionally 7- plants in three height classes:, early sapling, 61-134 cm; lobed or 3-lobed (Radford et al., 1968; Cocke, 1974; large seedlings, 10-23 cm; and small seedlings (mostly first Grimm, 1983; Duncan & Duncan, 1988). The tips of the year), 3-8.5 cm. All of the small seedlings were within 5 lobes are acute and leaf margins are serrate, rarely entire. meters of the atypical specimen and most of the large In 1991, I found a seedling (2-3 yr old) that I seedlings and saplings were within 10 meters. The greatest tentatively identified as a specimen of Liquidambar styrac- distance between any two plants was 70 meters. All of the iflua. The specimen occurs in a 20 acre section of plants measured were in dense to moderate shade. In the deciduous forest located between U.S. Route 1 and seedling classes, three leaves were measured from each of Waverly Drive, 3.2 km south of Ladysmith, Caroline ten plants (n = 30 leaves). In the sapling class, counts of County, Virginia. The seedling was found at the middle leaf lobes and observations of lobe tips and leaf margins of a 10% slope. Dominant trees on the upper slope were made from ten leaves from each of 20 plants (n include Quercus alba L., Q. -

Australlam Natlve PLANTS SOCIETY AUSTRALIA H a K W

AUSTRALlAM NATlVE PLANTS SOCIETY AUSTRALIA HAKW STUDY GROUP NEWSLETTER No, 57 Leader Paul Kennedy OAM 210 Aireys Street Elliminyt 3250 Tel. 03-52315569 Internet hakeaholic@~rnail.com Dear Members. January 2015 has arrived with major variations in our weather, hot days, bush fires and now days of rain and cool weather. Our Australian plants have to adjust to a wealth of climatic conditions. Here in Colac it has been fairly mild. The drier than normal conditions continued through November and December with maximum daytime temperatures seldom reaching 30 degrees C. In early January there were three days of temperatures in the high thirtys but then the rain came and we are back to cooler weather. Rainfall for January was 70mm. The Hakeas have put on a fair degree of growth, most tripling their height since they went in. Out of ninety species only two have died probably due to poor root development and wind. Colac is a windy place and most of the Hakeas have been subject to strong winds. I have been planting the taller species such as macraeana, salicifolia fine leaf, drupacea and oleifolia on the perimeter to hopefully deflect some of the wind across the property. The original two truck loads of native mulch have been spread over five sheets of newspaper on the garden beds and has been very effective in reducing weed growth. I was hoping for another truckload of native mulch but had to settle for a load of pine bark which is now being spread on the remaining raised up beds. I am putting it on thinly as I want any moisture to go through to the soil belm~Tkepheba~k wilttakelongw tobreak down tse, In-rren urbanareaswhere bush fires could- - occur I would recommend a gravel mulch as wood mulch burns and only does more damage to the plants. -

Wood from Midwestern Trees Purdue EXTENSION

PURDUE EXTENSION FNR-270 Daniel L. Cassens Professor, Wood Products Eva Haviarova Assistant Professor, Wood Science Sally Weeks Dendrology Laboratory Manager Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University Indiana and the Midwestern land, but the remaining areas soon states are home to a diverse array reforested themselves with young of tree species. In total there are stands of trees, many of which have approximately 100 native tree been harvested and replaced by yet species and 150 shrub species. another generation of trees. This Indiana is a long state, and because continuous process testifies to the of that, species composition changes renewability of the wood resource significantly from north to south. and the ecosystem associated with it. A number of species such as bald Today, the wood manufacturing cypress (Taxodium distichum), cherry sector ranks first among all bark, and overcup oak (Quercus agricultural commodities in terms pagoda and Q. lyrata) respectively are of economic impact. Indiana forests native only to the Ohio Valley region provide jobs to nearly 50,000 and areas further south; whereas, individuals and add about $2.75 northern Indiana has several species billion dollars to the state’s economy. such as tamarack (Larix laricina), There are not as many lumber quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), categories as there are species of and jack pine (Pinus banksiana) that trees. Once trees from the same are more commonly associated with genus, or taxon, such as ash, white the upper Great Lake states. oak, or red oak are processed into In urban environments, native lumber, there is no way to separate species provide shade and diversity the woods of individual species.