Insert Background & Methodology Cover Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Airways Response

From: British Airways Customer Relations <[email protected]> Date: 17 April 2015 at 10:49 Subject: Your Response from BA Customer Relations To: [email protected] **Please DO NOT reply directly to this email by using the ‘reply’ function on your personal email settings, as it WILL NOT be received. If you wish to send us a reply please use the link at the bottom of the email** Dear Mr Dial Thank you for your letter dated 26 March addressed to Silla Maizey and the Executive Chairman, Keith Williams about been downgraded on flight BA0191 on 13 March. Keith has asked me to reply to you on his behalf and so this is not a standard email. I apologise on behalf of British Airways for not contacting you proactively about this matter and for the delay in my personal response. I see from your booking that you purchased the ticket to Austin on 04 November 2014 through you travel agent Opodo. I completely understand your frustration at booking this ticket so far in advance and arriving at the airport to find you've been downgraded from the Club World cabin. I hope our staff explained that there are occasions where our customers make a booking and then don’t turn up for their flight. We, along with other airlines, have an overbooking policy, which helps us avoid flying with empty seats and means we can keep the cost of our fares down. Ultimately this means we can fly a lot more passengers to their destinations. We collect data about how many people don’t turn up for each flight and we use this information to tell us if we should book more passengers than there are seats. -

(First Chamber) 17 December 2003 * in Case T-219/99, British Airways

BRITISH AIRWAYS v COMMISSION JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE (First Chamber) 17 December 2003 * In Case T-219/99, British Airways pic, established in Waterside (United Kingdom), represented by W. Allan and O. Black, solicitors, W. Wood and H. Davies, barristers, with an address for service in Luxembourg, applicant, v Commission of the European Communities, represented by M. Erhart, acting as Agent, and A. Barav, barrister, with an address for service in Luxembourg, defendant, • Language (if the case: English. II - 5925 JUDGMENT OF 17. 12. 2003 — CASE T-219/99 supported by Virgin Atlantic Airways Ltd, established in Crawley (United Kingdom), represented by P. Binetter, solicitor, N. Green and C. West, barristers, intervener, APPLICATION for the annulment under Article 230 EC of Commission Decision 2000/74/EC of 14 July 1999 relating to a proceeding under Article 82 of the EC Treaty (IV/D-2/34.780 — Virgin/British Airways) (OJ 2000 L 30, p. 1), THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES (First Chamber), composed of: B. Vesterdorf, President, M. Jaeger and H. Legal, Judges, Registrar: J. Palacio González, Principal Administrator, having regard to the written procedure and further to the hearing on 26 February 2003, II - 5926 BRITISH AIRWAYS v COMMISSION gives the following Judgment Background to the dispute 1 According to the first recital in the preamble to Commission Decision 2000/74/EC of 14 July 1999 relating to a proceeding under Article 82 of the EC Treaty (IV/D-2/34.780 — Virgin/British Airways) (OJ 2000 L 30, p. 1; 'the contested decision'), British Airways pic ('BA') is the largest British airline company. -

2001/2002 Annual Report & Accounts

2001/2002 Annual Report & Accounts Key Results 2001-02 2000-01 Group results Turnover m down 10.1% 8,340 9,278 Operating (loss)/profit m n/m (110) 380 (Loss)/profit before taxation m n/m (200) 150 Attributable (loss)/profit for the year m n/m (142) 67 Equity shareholders’ funds m down 5.1% 2,207 2,325 Basic (loss)/earnings per share p n/m (13.2) 6.2 Key financial statistics Airline operations yield p/RPK up 4.7% 6.67 6.37 Operating margin % down 5.4 points (1.3) 4.1 Net debt/total capital ratio % up 1.5 points 66.0 64.5 Operating statistics Passengers carried group ’000 down 10.0% 40,004 44,462 Revenue passenger kilometres group m down 13.7% 106,270 123,197 Revenue tonne kilometres group m down 13.9% 14,632 16,987 Available tonne kilometres group m down 9.3% 22,848 25,196 Passenger load factor group % down 1.0 points 70.4 71.4 British Airways share price Key results 1 Group profit and loss account 21 Net (loss)/income under US GAAP 57 Statement from the Chairman 2 Balance sheets 22 Shareholders’ equity under US GAAP 59 St a t ement from the Chief Exec u t i v e 4 Group cash flow statement 23 Operating and financial statistics 60 Operating and financial review 5 Statement of total recognised gains Five year summaries 61 Board members, and leadership team 11 and losses 24 Aircraft fleet 63 Directors’ report 12 Reconciliation of movements Shareholder information 64 Remuneration report 16 in shareholders’ funds 24 Glossary IBC Directors’ remuneration and Summary statements in euro 25 share interests 17 Notes to the accounts 26 Statement of directors’ responsibilities 20 Principal investments 54 Report of the auditors to the members United States generally accepted accounting of British Airways Plc 20 principles (US GAAP) information 55 British Airways 01/02 Annual Report 1 Urgent reaction to the post-September crisis included moves to Chairman’s Statement re s u s c i t a t e the market with an innova t i v e range of special offers and in c e n t i v es. -

Interim Results 1998-99

PRELIMINARY FINANCIAL RESULTS 2000-2001 Three months ended Twelve months ended March 31 Increase/ March 31 Increase/ 2001 2000 (Decrease) 2001 2000 (Decrease) Turnover £m 2,121 2,107 0.7% 9,278 8,940 3.8% Operating profit / (loss) £m (61) (125) 51.2% 380 84 nm Operating margin % (2.9) (5.9) 3.0pts 4.1 0.9 3.2pts Profit/(loss) before tax £m (65) (175) 62.9% 150 5 nm Retained loss for the period £m (215) (306) 29.7% (79) (216) 63.4% Capital and reserves at period end £m 3,419 3,340 2.4% 3,419 3,340 2.4% Earnings per share Basic p (7.2) (15.7) 54.1% 10.6 (2.0) nm Diluted p n/a n/a n/a 10.5 n/a n/a Dividends per share p 12.8 12.8 17.9 17.9 n/a: Not applicable nm : Not meaningful Shareholder Value Waterside (HBA1) PO Box 365, Harmondsworth West Drayton, Middlesex UB7 OGB Tel: +44 (0) 208 738 6947 Fax: +44 (0) 208 738 9602 Page 1 GROUP PROFIT AND LOSS ACCOUNT Three months ended Twelve months ended March 31 Increase/ March 31 Increase/ 2001 £m 2000 £m (Decrease) 2001 £m 2000 £m(Decrease) Traffic Revenue Scheduled Passenger 1,787 1,760 1.5% 7,803 7,465 4.5% Scheduled Cargo 133 134 (0.7)% 579 556 4.1% Non-scheduled services 7 8 (12.5)% 50 71 (29.6)% 1,927 1,902 1.3% 8,432 8,092 4.2% Other revenue 194 205 (5.4)% 846 848 (0.2)% TOTAL TURNOVER 2,121 2,107 0.7% 9,278 8,940 3.8% Employee costs 611 607 0.7% 2,376 2,481 (4.2)% Depreciation 183 172 6.4% 715 648 10.3% Aircraft operating lease costs 58 52 11.5% 221 190 16.3% Fuel and oil costs 280 219 27.9% 1,102 804 37.1% Engineering and other aircraft costs 163 141 15.6% 662 661 0.2% Landing fees and -

Letter from Sean Doyle, CEO British Airways, to Committee in Response

Sean L Doyle Chief Executive Officer Waterside (HBB3) PO Box 365 Harmondsworth UB7 0GB UK [email protected] 9th December 2020 Huw Merriman MP Chair of the Transport Committee House of Commons London SW1A 0AA By email to: [email protected] [email protected] Dear Huw Many thanks for your recent letter. I am glad that Alex Cruz was able to reassure the Committee on the issues raised when he appeared before you in September. I have set out below a response to the questions you asked in relation to progress in British Airways’ restructuring due to Covid-19, customer service manager contracts and slots. I have also included some information on the topic of the age profile of pilots leaving the business which I understand the Committee was interested in. Restructuring due to Covid-19 The impact of the pandemic on airlines across the world has been severe and British Airways has been working tirelessly to get through the immediate, and ongoing, crisis, as well as prepare for a very different future. In doing so all our efforts have been directed towards saving jobs and making sure that we are fit to meet the challenges ahead. Since the Committee session in September, agreements have been reached with the Trade Unions representing the main staff groups across British Airways. As you point out, those agreements avoid the signing of new contracts through agreed variations to existing contracts, as we have endeavoured to achieve from the outset of the consultation process. From our cabin crew community, no Cabin Service Managers (CSMs) were required to sign new contracts or were given new contracts for old. -

BA349 Cover Vaw5

www.britishairways.com 99/20001999/2000 Annual Report & Accounts General enquiries: 0845 77 999 77 Year at a glance • Worst result in eighteen years but dividend held. • e-business strategy unveiled, including plans to increase on-line commercial activity, smarter • Delivery of the new strategy under way, with ways to work and plans for several e-ventures new aircraft, new products and training for a new to capitalise on the airline’s assets. service style. • Further progress made with oneworld alliance • Significant investment announced in 21st Century partners, including combining sales functions in Travel, with flat beds in Club World, a new World the Far East and schedule changes with Qantas, Traveller Plus cabin, upgrades to Club Europe, and investment in a 9% stake in Iberia. Concorde and First and ongoing implementation • A Y2K bug-free entry into the new Millennium, ™ of the seat-back video and other improvements oneworld – the alliance of British Airways, American Airlines, with the British Airways London Eye adding to to World Traveller. the celebrations. • The Business Efficiency Programme exceeds Cathay Pacific, Finnair, Iberia and Qantas will be further strengthened • Bob Ayling resigned as Chief Executive its £1 billion target. in March 2000, after 15 years’ service with in 2000 when it is joined by Aer Lingus and LanChile. • Nine major new initiatives to improve the the airline. Rod Eddington appointed profitability of the company launched. Chief Executive, with effect from 1 May 2000. Our vision is to make global travel -

British Airways Plc Year Ended 31 December 2017

British Airways Plc Annual Report and Accounts Year ended 31 December 2017 Company registration number: 1777777 This page has been intentionally left blank Contents Officers and professional advisers 1 Strategic and directors’ reports Strategic report Management review and outlook 2 Financial review 6 Principal risks and uncertainties 10 Directors’ report 13 Directors’ responsibilities statement in relation to the financial statements 16 Independent auditor’s report 17 Group financial statements Group consolidated income statement 23 Group statement of other comprehensive income 24 Balance sheets 25 Cash flow statements 26 Statements of changes in equity 27 Notes to the financial statements 28 Subsidiary undertakings and other investments 84 Operating and financial statistics 86 Fleet table 87 Glossary 88 Officers and professional advisers Directors Alex Cruz (Chairman & Chief Executive Officer) Alison Reed (Deputy Chairman) Steve Gunning (Chief Financial Officer) Gavin Patterson Julia Simpson Lynne Embleton Secretary Andrew Fleming Registered office Waterside PO Box 365 Harmondsworth UB7 0GB Parent company International Consolidated Airlines Group S.A. (‘IAG’) El Caserío, Iberia Zona Industrial nº 2 (La Muñoza) Camino de La Muñoza, s/n, 28042 Madrid Spain Independent auditor Ernst & Young LLP 1 More London Place London SE1 2AF 1 Strategic report The Directors present their strategic report for the year ended 31 December 2017. British Airways Plc (‘British Airways’, ‘BA’, ‘the airline’ or ‘the Group’) is the UK’s largest international scheduled airline and one of the world’s leading global premium airlines. The Group’s principal place of business is London with significant presence at Heathrow, Gatwick and London City airports. As part of IAG and together with joint business, codeshare and franchise partners, British Airways operates one of the most extensive international scheduled airline networks. -

British Airways Profile

SECTION 2 - BRITISH AIRWAYS PROFILE OVERVIEW British Airways is the world's second biggest international airline, carrying more than 28 million passengers from one country to another. Also, one of the world’s longest established airlines, it has always been regarded as an industry-leader. The airline’s two main operating bases are London’s two main airports, Heathrow (the world’s biggest international airport) and Gatwick. Last year, more than 34 million people chose to fly on flights operated by British Airways. While British Airways is the world’s second largest international airline, because its US competitors carry so many passengers on domestic flights, it is the fifth biggest in overall passenger carryings (in terms of revenue passenger kilometres). During 2001/02 revenue passenger kilometres for the Group fell by 13.7 per cent, against a capacity decrease of 9.3 per cent (measured in available tonne kilometres). This resulted in Group passenger load factor of 70.4 per cent, down from 71.4 per cent the previous year. The airline also carried more than 750 tonnes of cargo last year (down 17.4 per cent on the previous year). The significant drop in both passengers and cargo carried was a reflection of the difficult trading conditions resulting from the weakening of the global economy, the impact of the foot and mouth epidemic in the UK and effects of the September 11th US terrorist attacks. An average of 61,460 staff were employed by the Group world-wide in 2001-2002, 81.0 per cent of them based in the UK. -

British Airways Open Letter – First Published On

British Airways Open Letter – First published on www.squiss.co.uk Sir Martin Broughton, Chairman & Keith Williams, CEO British Airways Waterside Speedbird Way off Bath Road Harmondsworth UB7 0GA Dear Sir Martin & Mr Williams Last night I won first prize in British Airways' baggage competition! I am delighted to report I won a tiny stick of deodorant, some shower gel, a flimsy toothbrush, one portion of toothpaste (for those who don't like to clean their teeth at night and in the morning) and an XL white t-shirt, which my wife and I should be able to wear simultaneously. I think I did rather well considering the entry price was just three taxi rides, a suitcase, clothes, a wash bag, car keys... On the bright side, my luggage is enjoying a mystery trip while I am still in possession of the socks I worked and travelled in yesterday. Hurrah! For some reason, which was never fully explained, our 21:45 flight (BA0401) from Brussels to Heathrow was delayed by about an hour. Then, a little over an hour later, BA ramped up the excitement substantially when not one but two of the extending walkways failed to extend to allow my fellow passengers and I to alight. I can assure you the banter on board was both jocular and very complimentary. Whilst the enjoyment ended there for most of the passengers, I was fortunate to be one of six specially selected winners who were awarded quality time together around the luggage carousel watching the empty spaces grow as cases were removed and ours failed to take their places. -

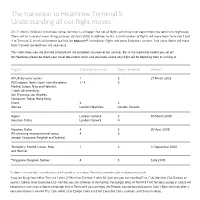

The Transition to Heathrow Terminal 5 Understanding All Our Flight Moves

The transition to Heathrow Terminal 5 Understanding all our flight moves On 27 March 2008 our brand new home, Terminal 5, will open. But not all flights will arrive at or depart from the terminal straightaway. There will be a second move taking place on 30 April 2008. In addition to this, a small number of flights will move from Terminals 1 and 4 to Terminal 3, which will become our hub for oneworld® Australasian flights and some European services. And some flights will move from Gatwick to Heathrow and vice versa. This table shows you the planned schedule for the complete transition of our services. But in the meantime, before you set off for Heathrow, please do check your travel documents to be sure you know where your flight will be departing from or arriving at. Flights Current terminal New terminal When? All UK domestic routes 1 5 27 March 2008 All European flights (apart from Barcelona, 1 / 4 5 Madrid, Lisbon, Nice and Helsinki), Tripoli, Johannesburg, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Vancouver, Tokyo, Hong Kong Miami 3 5 Warsaw London Heathrow London Gatwick Algiers London Gatwick 5 30 March 2008 Houston, Dallas London Gatwick 4 Houston, Dallas 4 5 30 April 2008 All remaining intercontinental routes 4 5 (except Singapore, Bangkok and Sydney) *Barcelona, Madrid, Lisbon, Nice 1 3 17 September 2008 and Helsinki *Singapore, Bangkok, Sydney 4 3 Early 2009 *In addition codeshare flights operated by Iberia and Finnair will also be moving to Terminal 3 in September 2008 and Qantas in early 2009. If you are flying from either Terminal 1 after 27 March or Terminal 4 after 30 April and you are travelling First, Club World or Club Europe, or you’re a Gold or Silver Executive Club member, you can still enjoy all the facilities the lounges offer. -

Our Business

18 / British Airways 2008/09 Annual Report and Accounts Our business The global airline industry is fiercely competitive, heavily regulated and highly exposed to changes in customer behaviour and consumer confidence. The current economic environment presents a new challenge. We must concentrate our efforts to seize long-term opportunities for growth. British Airways 2008/09 Annual Report and Accounts / 19 The markets we operate in Overview Market overview already begun in earnest, forcing many Global premium airlines into financial loss. demand in key markets The pace of economic slowdown during Even at these lower levels, fuel remains North Atlantic the year was faster than most had +1.2% a much bigger proportion of airline costs predicted. What had first been expected -17.9% to be a downturn in key developed compared to a few years ago, and the Within Europe economies turned into a global recession prospect of renewed volatility in prices -9.5% remains a long-term concern. in the autumn of 2008. With record oil -24.1% and commodity prices, sterling collapse The most significant impact of the Within Far East and an unprecedented financial crisis all downturn has been on premium -6.6% striking at once, even those emerging passengers, with businesses looking to -26.3% economies that had been expected to cut back sharply on travel to save money. Europe – Far East go untouched by recession saw sharp Our business IATA’s latest figures show that global -2.8% declines in growth. premium traffic fell in 2008 by 2.8 per -20.3% In the UK, growth began slowing in the first cent. -

List of EU Air Carriers Holding an Active Operating Licence

Active Licenses Operating licences granted Member State: Austria Decision Name of air carrier Address of air carrier Permitted to carry Category (1) effective since ABC Bedarfsflug GmbH 6020 Innsbruck - Fürstenweg 176, Tyrolean Center passengers, cargo, mail B 16/04/2003 AFS Alpine Flightservice GmbH Wallenmahd 23, 6850 Dornbirn passengers, cargo, mail B 20/08/2015 Air Independence GmbH 5020 Salzburg, Airport, Innsbrucker Bundesstraße 95 passengers, cargo, mail A 22/01/2009 Airlink Luftverkehrsgesellschaft m.b.H. 5035 Salzburg-Flughafen - Innsbrucker Bundesstraße 95 passengers, cargo, mail A 31/03/2005 Alpenflug Gesellschaft m.b.H.& Co.KG. 5700 Zell am See passengers, cargo, mail B 14/08/2008 Altenrhein Luftfahrt GmbH Office Park 3, Top 312, 1300 Wien-Flughafen passengers, cargo, mail A 24/03/2011 Amira Air GmbH Wipplingerstraße 35/5. OG, 1010 Wien passengers, cargo, mail A 12/09/2019 Anisec Luftfahrt GmbH Office Park 1, Top B04, 1300 Wien Flughafen passengers, cargo, mail A 09/07/2018 ARA Flugrettung gemeinnützige GmbH 9020 Klagenfurt - Grete-Bittner-Straße 9 passengers, cargo, mail A 03/11/2005 ART Aviation Flugbetriebs GmbH Porzellangasse 7/Top 2, 1090 Wien passengers, cargo, mail A 14/11/2012 Austrian Airlines AG 1300 Wien-Flughafen - Office Park 2 passengers, cargo, mail A 10/09/2007 Disclaimer: The table reflects the data available in ACOL-database on 16/10/2020. The data is provided by the Member States. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy or the completeness of the data included in this document nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. 1 Active Licenses Decision Name of air carrier Address of air carrier Permitted to carry Category (1) effective since 5020 Salzburg-Flughafen - Innsbrucker Bundesstraße AVAG AIR GmbH für Luftfahrt passengers, cargo, mail B 02/11/2006 111 Avcon Jet AG Wohllebengasse 12-14, 1040 Wien passengers, cargo, mail A 03/04/2008 B.A.C.H.