Heathrow's Initial Business Plan Detailed Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Heathrow Airport

Document Code : PRO067GVAE0809 Into-plane Fuels Management System From Fuel Farm to Take Off London Heathrow Airport Varec representatives traveled to London Heathrow Airport Our Client to meet with Swissport Fueling Services and British Airways Swissport Fuelling Services provides high quality, representatives to discuss automating both organizations’ independent aviation fuel handling on behalf of airlines, fuels management processes at the airport. airports and fuel suppliers worldwide. Swissport is a leader Swissport already used FuelsManager® Accounting in the fuelling industry for on-time performance, and software for reconciliation and reporting to the fuel has a proven track record for maintaining aviation fuel depot consortium operator. British Airways also used systems with a focus on safety, cost control and inventory the transaction information in the Varec Data Center to management. manually validate uplifts against the corresponding fuel debits by the consortium operator. London Heathrow Airport It seemed a natural step to integrate further and automate London Heathrow Airport (LHR) is the busiest airport in manual activities so that the fuels accounting processes the United Kingdom, as well as the sixth busiest airport could be performed more efficiently, accurately and timely. in the world by total passenger traffic. In 2015, it handled Within two weeks of implementating the new system, the first dispatched flight and fuelling transaction data was a record 75 million passengers. It is the primary hub for captured successfully. British Airways, and is used by over 80 other airlines flying to 185 destinations in 84 countries. Swissport Fuelling Swissport realized an immediate increase in fuel agent Service provides into plane fuelling services for British productivity and improved accuracy when dispatching and Airways and Air Canada at London Heathrow Airport. -

How to Get to Heathrow Airport and Meeting Point

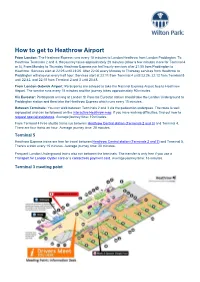

How to get to Heathrow Airport From London: The Heathrow Express runs every 15 minutes to London Heathrow from London Paddington. To Heathrow Terminals 2 and 3, the journey takes approximately 20 minutes (allow a few minutes more for Terminal 4 or 5). From Monday to Thursday Heathrow Express run half hourly services after 21:55 from Paddington to Heathrow. Services start at 22:25 until 23:25. After 22:00 every Monday to Thursday services from Heathrow to Paddington will also run every half hour. Services start at 22:11 from Terminal 4 until 23:26, 22:12 from Terminal 5 until 22:42, and 22:18 from Terminal 2 and 3 until 23:48. From London Gatwick Airport: Participants are advised to take the National Express Airport bus to Heathrow Airport. The service runs every 15 minutes and the journey takes approximately 90 minutes. Via Eurostar: Participants arriving at London St Pancras Eurostar station should take the London Underground to Paddington station and then take the Heathrow Express which runs every 15 minutes. Between Terminals: You can walk between Terminals 2 and 3 via the pedestrian underpass. The route is well signposted and can be followed on the interactive Heathrow map. If you have walking difficulties, find out how to request special assistance. Average journey time: 10 minutes. From Terminal 4 Free shuttle trains run between Heathrow Central station (Terminals 2 and 3) and Terminal 4. There are four trains an hour. Average journey time: 20 minutes. Terminal 5 Heathrow Express trains are free for travel between Heathrow Central station (Terminals 2 and 3) and Terminal 5. -

London Heathrow International Airport Terminal 5

Concepts Products Service London Heathrow International Airport Terminal 5 1 Project Report London Heathrow International Airport Terminal 5 The UK’s largest free standing building. The new Terminal 5, developed by BAA for the exclusive use of British Airways at London Heathrow International Airport, is one of the largest airport terminals in the world. The whole Terminal 5 has five floors, each the size of ten football pitches, redefining the passenger experience at Heathrow Airport and setting new standards both in terminal design and customer satisfaction. The development provides Europe’s largest and most overcrowded airport with the capacity to handle an additional 30 - 35 million passengers per annum. London Heathrow International Airport Terminal 5 Developer: BAA plc Architects: Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (formerly Richard Rogers Partnership) / Pascall & Watson Ltd Tenant: British Airways plc 2 Building new solutions. Lindner undertakes major worldwide projects in all areas of interior finishes, insulation technology, industrial services and building facades. From pre-planning through to project completion Lindner is your partner of choice. The Company’s extensive manufacturing capability enables quality to be strictly maintained whilst allowing maximum flexibility to meet individual project requirements. Environmental considerations are fundamental to all Lindner’s business principles. Through partnerships with clients Lindner turns concepts into reality. 3 Our business activities at T5 The following products were designed, manufactured and installed by Lindner - Facades - Drop & Slide Ceilings - Disc Ceilings - Raft Ceilings - Mesh Ceilings - Tubular Ceilings - Partitions - Beacons and FID Trees 4 5 Facades 6 The facade of a building is the most important part of the cladding. Terminal 5´s facades are made up of over 45,000 m² of glass, equating to 7,500 bespoke glass panels and were installed in T5A and T5B, the Car Park, the Control Tower and also at the Rail Station. -

London Heathrow Airport

London Heathrow Airport Located 20 miles to the west of Central London. www.heathrowairport.com Heathrow Airport by Train The Heathrow Express is the fastest way to travel into Central London. Trains leave Heathrow Airport from approximately 5.12am until 11.40pm. For more information, and details of fares, visit the Heathrow Express website. Operating 150 services every day, Heathrow Express reaches Heathrow Central (Terminals 1 and 3) from Paddington in 15 minutes, with Terminal 5 a further four minutes. A free transfer service to Terminal 4 departs Heathrow Central every 15 minutes and takes four minutes. Heathrow Connect services run from London Paddington, calling at Ealing Broadway, West Ealing, Hanwell, Southall, Hayes & Harlington and Heathrow Central (Terminals 1 and 3). For Terminals 4 and 5, there's a free Heathrow Express tr ansfer service from Heathrow Central. Heathrow Connect journey time is about 25 minutes from Paddington to Heathrow Central. For more information, and details of fares, visit the Heathrow Connect website. Heathrow Airport by Tube The Piccadilly line connects Heathrow Airport to Central London and the rest of the Tube system. The Tube is cheaper than the Heathrow Express or Heathrow Connect but it takes a lot longer and is less comfortable. Tube services leave Heathrow every few minutes from approximately 5.10am (5.45am Sundays) to 11.35pm (11.25pm Sundays). Journey time to Piccadilly Circus is about 50 minutes. There are three Tube stations at Heathrow Airport, serving Terminals 1-3, Terminal 4 and Terminal 5. For more information, and details of fares, visit the Transport for London (TfL) website. -

Transport with So Many Ways to Get to and Around London, Doing Business Here Has Never Been Easier

Transport With so many ways to get to and around London, doing business here has never been easier First Capital Connect runs up to four trains an hour to Blackfriars/London Bridge. Fares from £8.90 single; journey time 35 mins. firstcapitalconnect.co.uk To London by coach There is an hourly coach service to Victoria Coach Station run by National Express Airport. Fares from £7.30 single; journey time 1 hour 20 mins. nationalexpress.com London Heathrow Airport T: +44 (0)844 335 1801 baa.com To London by Tube The Piccadilly line connects all five terminals with central London. Fares from £4 single (from £2.20 with an Oyster card); journey time about an hour. tfl.gov.uk/tube To London by rail The Heathrow Express runs four non- Greater London & airport locations stop trains an hour to and from London Paddington station. Fares from £16.50 single; journey time 15-20 mins. Transport for London (TfL) Travelcards are not valid This section details the various types Getting here on this service. of transport available in London, providing heathrowexpress.com information on how to get to the city On arrival from the airports, and how to get around Heathrow Connect runs between once in town. There are also listings for London City Airport Heathrow and Paddington via five stations transport companies, whether travelling T: +44 (0)20 7646 0088 in west London. Fares from £7.40 single. by road, rail, river, or even by bike or on londoncityairport.com Trains run every 30 mins; journey time foot. See the Transport & Sightseeing around 25 mins. -

Systems Integration at London Heathrow Terminal 5

CMR 420, 02/01/09 Winter 2009 | Vol.51, No.2 | REPRINT SERIES CaliforniaReview Management Innovation in Megaprojects: Systems Integration at London Heathrow Terminal 5 Andrew Davies David Gann Tony Douglas © 2009 by The Regents of the University of California Innovation in Megaprojects: SYSTEMS INTEGRATION AT LONDON HEATHROW TERMINAL 5 Andrew Davies David Gann Tony Douglas growing number of infrastructure projects are being proposed and built throughout the world. A megaproject is an investment of $1B or more to build the physical infrastructures that enable people, resources, and information to move within buildings and betweenA locations throughout the world. Organizations responsible for produc- ing megaprojects face a “performance paradox.” Despite the growth in number and opportunities to benefit from learning, megaprojects continue to have poor performance records.1 Most are unsuccessful measured against their original time, cost, quality, and safety objectives, as well as their expected revenue predictions. The construction of airport infrastructure provides examples of how megaprojects can go wrong. When Denver’s $5B international airport opened in 1995, it was almost 200 per cent over the original budget, 16 months late, and passenger traffic achieved only half the predicted revenues. The opening of the airport was plagued by problems with the baggage handling system, which was eventually abandoned in August 2005. Although Hong Kong’s $20B Chek Lap Kok airport opened on time in July 1998, severe disruptions were experienced for six months after opening due to computer problems with the baggage han- dling system. The authors thank Jennifer Whyte, Catelijne Coopmans, and Tim Brady, who worked on a larger study of the T5 project with us, and four anonymous referees who helped to develop our conceptual approach. -

British Airways Response

From: British Airways Customer Relations <[email protected]> Date: 17 April 2015 at 10:49 Subject: Your Response from BA Customer Relations To: [email protected] **Please DO NOT reply directly to this email by using the ‘reply’ function on your personal email settings, as it WILL NOT be received. If you wish to send us a reply please use the link at the bottom of the email** Dear Mr Dial Thank you for your letter dated 26 March addressed to Silla Maizey and the Executive Chairman, Keith Williams about been downgraded on flight BA0191 on 13 March. Keith has asked me to reply to you on his behalf and so this is not a standard email. I apologise on behalf of British Airways for not contacting you proactively about this matter and for the delay in my personal response. I see from your booking that you purchased the ticket to Austin on 04 November 2014 through you travel agent Opodo. I completely understand your frustration at booking this ticket so far in advance and arriving at the airport to find you've been downgraded from the Club World cabin. I hope our staff explained that there are occasions where our customers make a booking and then don’t turn up for their flight. We, along with other airlines, have an overbooking policy, which helps us avoid flying with empty seats and means we can keep the cost of our fares down. Ultimately this means we can fly a lot more passengers to their destinations. We collect data about how many people don’t turn up for each flight and we use this information to tell us if we should book more passengers than there are seats. -

Methodical Approach to Determining the Capacity Utilisation of Airports: the Development of the European Air Traffic System Between 2008 and 2012

Deutscher Luft- und Raumfahrtkongress 2014 DocumentID: 340138 METHODICAL APPROACH TO DETERMINING THE CAPACITY UTILISATION OF AIRPORTS: THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE EUROPEAN AIR TRAFFIC SYSTEM BETWEEN 2008 AND 2012 C. Schinwald, Munich Aerospace, Faculty of aerospace engineering e.V., Lyonel-Feininger-Str. 28, 80807 Munich, Germany M. Hornung, Institute of Aircraft Design, Technical University of Munich, Boltzmannstr. 15, 85748 Garching, Germany Abstract The global air transport system has seen significant growth rates over recent decades. The exponential increase in passenger numbers were only interrupted by periods of stagnation caused by the negative effects of unpredictable crises. In the future, the total number of aircraft movements is expected to grow further at rates between 4 and 5% per year. As seen in the past, the growth of the air transportation sector is highly asymmetric, which means that it varies strongly from region to region. This forecasted increase in demand is mainly caused by the augmented travel needs of the world's population and the rising wealth of its peoples. Because airports and, more precisely, the runway systems usually represent the bottleneck of the entire air transport system, this paper will focus on these elements. Due to local constraints, many airports haven’t been able to expand their infrastructure at the same speed traffic has grown. Therefore, more and more airports are operating close to their maximum capacity. This development is confirmed by continuously increasing average delays. This paper demonstrates a methodical approach which allows the determining of the degree of capacity utilisation of an airport. The Basic Load Index (BLI) and the Peak Load Index (PLI) were defined as indicators for the capacity situation of an airport. -

Advances in Earthquake Source Physics Workshop 1St - 2Nd September 2014 Gustave Tuck Lecture Theatre University College London

Advances in Earthquake Source Physics Workshop 1st - 2nd September 2014 Gustave Tuck lecture theatre University College London In the following, the directions from every London airport, and from King's Cross/St. Pancras station, are detailed. Useful web links are also provided. UCL Department of Geography provides a very helpful interactive map of UCL and its surroundings, displayed at the end of this document. In the following text, references to this map will be used (e.g. UCL main gates: C3). Travelling in London can turn out to be quite expensive, especially if you intend to stay a little more than two days in London. Buying an Oyster card might be a good way to save some money. It only costs £5, and whatever the amount you want to top up at the beginning, and is quickly recovered. Then, you will just have to charge it whenever you need to. You can purchase an Osyter card at any airports and stations, or on the Transport For London website. From Heathrow Airport to UCL From Heathrow Airport, take the Heathrow Express from Heathrow Central station (Terminals 1-2-3) to London Paddington station. Use the airport train to connect from Terminals 4 or 5. Once in London Paddington station, use either the Circle or Hammersmith City underground lines to reach Euston Square station (C1). Head to the South exit, and take Gower St. towards South, walk past UCLU Lewis's café (C2), and the main gates to UCL (C3) will be on your left, facing the Cruciform building (B3). A cheaper way to connect to UCL from Heathrow Airport is to take the Piccadilly underground line from Heathrow Central station, up to Green Park station, and then commute to the Victoria line up to Warren Street station ( A1). -

Aldwych-House-Brochure.Pdf

Executive summary • An iconic flagship in the heart of Midtown • This imposing building invested with period grandeur, has been brought to life in an exciting and modern manner • A powerful and dramatic entrance hall with 9 storey atrium creates a backdrop to this efficient and modern office • A total of 142,696 sq ft of new lettings have taken place leaving just 31,164 sq ft available • A space to dwell… 4,209 – 31,164 SQ FT 4 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 5 Aldwych House • MoreySmith designed reception • Full height (9 storey) central atrium fusing a modern which provides a light, modern, interior with imposing spacious circulation area 1920s architecture • Floors are served by a newly refurbished lightwell on the west side and a dramatically lit internal Aldwych House totals 174,000 atrium to the east from lower sq ft over lower ground to 8th ground to 3rd floor floors with a 65m frontage • An extensive timber roof terrace onto historic Aldwych around a glazed roof area • Showers, cycle storage and a drying room are located in the basement with easy access from the rear of the building • The ROKA restaurant is on the ground floor 6 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 7 8 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM Floorplate Typical upper floor c. 18,000 sq ft Typical upper floor CGI with sample fit-out 10 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 11 Floorplate Typical upper floor with suite fit-out 12 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 13 SOHO TOTTENHAM COURT ROAD MIDTOWN | LONDON Aldwych House, now transformed as part of the dynamic re-generation of this vibrant eclectic midtown destination, stands tall and COVENT GARDEN commanding on the north of the double crescent of Aldwych. -

(First Chamber) 17 December 2003 * in Case T-219/99, British Airways

BRITISH AIRWAYS v COMMISSION JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE (First Chamber) 17 December 2003 * In Case T-219/99, British Airways pic, established in Waterside (United Kingdom), represented by W. Allan and O. Black, solicitors, W. Wood and H. Davies, barristers, with an address for service in Luxembourg, applicant, v Commission of the European Communities, represented by M. Erhart, acting as Agent, and A. Barav, barrister, with an address for service in Luxembourg, defendant, • Language (if the case: English. II - 5925 JUDGMENT OF 17. 12. 2003 — CASE T-219/99 supported by Virgin Atlantic Airways Ltd, established in Crawley (United Kingdom), represented by P. Binetter, solicitor, N. Green and C. West, barristers, intervener, APPLICATION for the annulment under Article 230 EC of Commission Decision 2000/74/EC of 14 July 1999 relating to a proceeding under Article 82 of the EC Treaty (IV/D-2/34.780 — Virgin/British Airways) (OJ 2000 L 30, p. 1), THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES (First Chamber), composed of: B. Vesterdorf, President, M. Jaeger and H. Legal, Judges, Registrar: J. Palacio González, Principal Administrator, having regard to the written procedure and further to the hearing on 26 February 2003, II - 5926 BRITISH AIRWAYS v COMMISSION gives the following Judgment Background to the dispute 1 According to the first recital in the preamble to Commission Decision 2000/74/EC of 14 July 1999 relating to a proceeding under Article 82 of the EC Treaty (IV/D-2/34.780 — Virgin/British Airways) (OJ 2000 L 30, p. 1; 'the contested decision'), British Airways pic ('BA') is the largest British airline company. -

Hilton London Euston the Facts

HILTON LONDON EUSTON THE FACTS AT A GLANCE Conveniently located in the heart of the capital, set in a charming Victorian townhouse, Hilton London Euston combines heritage with a contemporary style. • £10m refurbishment completed summer 2016 Ideal for business or leisure, this distinctive hotel offers an outstanding choice • 156 guest rooms and family rooms of accommodation with upscale amenities, fine dining and state-of-the-art • Woburn Place Restaurant & Lounge meeting rooms – all supported with friendly and professional service. • Mulberry’s Restaurant • 7 flexible meeting and conference rooms Located just three minutes’ walk from Euston Station and ten minutes from • Close to Euston Station and King’s King’s Cross St Pancras, Hilton London Euston is an ideal base to explore the Cross St Pancras north. Along with six London Underground lines in the close proximity, the • A walking distance from Eurostar hotel remains one of the best-connected hotels in the capital. terminal with high speed connectivity to Continental Europe • Hilton Fitness by Precor® OUR ROOMS GUEST ROOMS Each bedroom is distinctive, functional and comfortable with modern amenities to suit the needs of the contemporary traveller. The large Victorian style windows provide an abundance of natural daylight. Bright and airy, each room includes a host of premium amenities, an easy chair, working area and a modern bathroom. Stay connected with complimentary wireless internet and enjoy movies on-demand on the flat-screen TV.* DELUXE ROOMS Guests can choose a distinctive Double Deluxe Guest Room or King Deluxe Guest Room to enjoy more space. A welcome amenity tray on arrival, fluffy Hilton bathrobes and slippers are some of the special touches in these deluxe rooms.