USHMM Finding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PLIC - METZ 1 Rue Antoine Louis 57000 METZ

PLIC - METZ 1 rue Antoine Louis 57000 METZ Insegnante: Cognome, N. progr. Denominazione Città/località macro-tipologia nome, corsi scuola sede del sede del corso corso (C) codice funzione (A) corso Docenti (B) ALTOMARE 1 THIONVILLE La Millaire EXT 1 Mauro EG 2 THIONVILLE Petite saison EXT 3 THIONVILLE Petite saison EXT APICELLA 4 FORBACH Marienau INT 2 Francesca EG 5 FORBACH Marienau INT 6 FORBACH Creutzberg EXT PETITE Cousteau EXT 7 ROSSELLE PETITE Vieille-Verrerie EXT 8 ROSSELLE BEHREN les Louis Pasteur EXT 9 FORBACH CREUTZWAL Schweitzer EXT 10 D STIRING Verrerie EXT 11 WENDEL Sophie BONETTI MAIZIERES 12 Les Ecarts EXT 3 Chiara EG LES METZ MAIZIERES Brieux EXT 13 LES METZ 14 METZ L. Pergaud EXT 15 METZ L. Pergaud EXT CHIAZZESE 16 MOYEUVRE Jobinot INT 4 Enza CICCARELLO 17 MOYEUVRE Jobinot INT EG 18 M0YEUVRE Jobinot INT 19 MOYEUVRE Jobinot INT 20 MOYEUVRE Jobinot INT 21 MOYEUVRE Jobinot INT 22 MOYEUVRE Jobinot INT 23 MOYEUVRE Jobinot INT 24 MOYEUVRE Jobinot INT 25 MOYEUVRE Jobinot INT 26 MOYEUVRE Jobinot INT 27 MOYEUVRE Jobinot INT 28 MOYEUVRE Jobinot INT AMANVILLER Ec. EXT 29 S Élémentaire DEMMERLE 30 EPINAL Ambrail EXT 5 Patricia EG 31 EPINAL Ambrail EXT FICICCHIA 32 BRIEY Prévert EXT 6 Carmela EG LOMBARDO 33 AMNEVILLE Ch. Peguy EXT 7 Aurélie EG 34 AMNEVILLE Ch. Peguy EXT 35 AMNEVILLE Ch. Peguy EXT 36 GUENANGE Saint Matthieu EXT 37 GUENANGE Saint Matthieu EXT Sainte GUENANGE EXT 38 Scholastique Sainte GUENANGE EXT 39 Scholastique 40 THIONVILLE V. Hugo EXT 41 THIONVILLE V. Hugo EXT MAIZIERES Mairie ADULTI 42 LES METZ MILAN Aurore 43 AVRIL J. -

Enim École Nationale D’Ingénieurs De Metz Metz

ENGINEERING SCHOOL ENIM ÉCOLE NATIONALE D’INGÉNIEURS DE METZ METZ At the heart of a partnership of National – A microstructures studies and mechanics Engineering schools (ENI) (Brest, Metz, of materials laboratory, LGIPM – computer St Étienne and Tarbes) and the University engineering, production and maintenance of Lorraine’s INP Collegium, the ENI Metz laboratory, LCFC – design, manufacturing ans control laboratory. The link between research and is a public university which, since 1962, engineering is a core strength of the curriculum, has been shaping qualified engineers in allowing us to constantly improve the quality of the fields of mechanical, material and teaching and give students greater access to industrial engineering, with teaching doctorates. Alongside their engineering training, based on a pragmatic and practical students can start preparing for a research Master’s degree via the 5th year specialisation approach. The school offers universal IDENTITY FORM and career-orientated courses lasting “research development and innovation”. either three or five years, and which are Precise name of the institution certified by the « Commission des Titres STRENGTHS ENIM - Ecole Nationale d’Ingénieurs de Metz d’Ingénieur » (CTI). The ENIM course ENIM stands out for the quality of its teaching Type of institution is tailored to the needs of businesses approach with many practical work and projects Public and to a constantly-changing world, for a pragmatic training in line with the evolving by maintaining strong links with the needs of companies and society. Thus, ENIM City where the main campus is located Metz industrial world and with its international trains field engineers, connected and engaged. -

Le Guide Des Producteurs

LE GUIDE DES PRODUCTEURS LE TALENT DES MOSELLANS EST SANS LIMITE Carte d’identité THIONVILLE de la Moselle FORBACH SAINT-AVOLD SARREGUEMINES METZ BITCHE CHÂTEAU-SALINS SARREBOURG Qualité MOSL : 2 un repère pour vous guider 3 1,047 MILLIONS Qualité MOSL vous permet de reconnaître les acteurs qui œuvrent sur le territoire mosellan et privilégient les productions locales et les savoir-faire propres au territoire. Vous pourrez le D’HABITANTS retrouver sur les produits alimentaires, les lieux de restauration, les sites ou activités touristiques. Le talent des mosellans est sans limite, profitez-en ! 2 6 216 KM DE Le logo Qualité MOSL apposé sur les produits agréés vous garantit une production locale SUPERFICIE de qualité. Chaque produit agréé Qualité MOSL répond à un cahier des charges strict. Il a fait DONT 50% DE l’objet d’un audit par un comité d’agrément constitué de professionnels et d’une procédure 2 400 encadrée par une charte dans laquelle le producteur s’engage à une transparence totale et une SURFACES AGRICOLES EXPLOITATIONS information claire sur l’origine des matières premières et les méthodes de production. Facilement AGRICOLES reconnaissable par les consommateurs, son logo permet une identification rapide des produits. ET 8 100 EMPLOIS En 2018 : près de 200 producteurs et artisans sont engagés dans cette démarche et près de 1000 DIRECTS produits portent l’agrément Qualité MOSL. 19 000 ENTREPRISES L’agrément Qualité MOSL est piloté par : ARTISANALES ET 100 000 SALARIÉS 70 HECTARES DE VIGNES AOC MOSELLE ET 250 000 BOUTEILLES PAR AN L’agriculture et l’artisanat mosellans L’agriculture mosellane, majoritairement quotidiens des populations. -

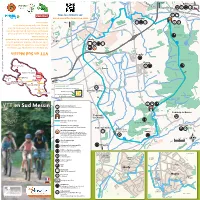

VTT En Sud Messin VTT En Sud Messin

D913 Berouard N 431 Bois Seille Bois Leussiotte la du Metz Peltre Peltre D155b Aérodrome Haut du chêne St-Pierre Crépy de Metz-Frescaty Ruisseau A31 Magny randonneurs. Metz Haut de Bouton P i D155c Messin, ainsi que des associations de de associations des que ainsi Messin, Le Grand l‘Etang Bousseux Bousseux de la Communauté de Communes du Sud du Communes de Communauté la de Grand La Mairie le D113a de Général de la Moselle, de Moselle Tourisme, Moselle de Moselle, la de Général du D913 Ruisseau Renaultrupt Bois de Il a été réalisé avec le concours du Conseil du concours le avec réalisé été a Il de Bouillon Crépy Grand Bois et de Randonnée. de et de Peltre Bois Ruisseau Ruisseau Martinet Départemental des Itinéraires de Promenade de Itinéraires des Départemental D68 Pré banna Marly JC Kany - Moselle Tourisme - CC du Sud Messin JC Kany - Moselle Tourisme Seille et Bois de l’Hôpital, est inscrit au Plan au inscrit est l’Hôpital, de Bois et Seille B Augny o is d la découverte en famille du Sud Messin entre Messin Sud du famille en découverte la e R Etang oy D113a e Peigneux N 431 mo Cet itinéraire de randonnée VTT, idéal pour idéal VTT, randonnée de itinéraire Cet nt Bois des Heures VTT en Sud Messin Sud en VTT Petit Pouilly Etang Bois de l’Hôpital Seille Les Chaudes Terres Au-dessus de l’Etang Ruisseau Fleury la Poncé A31 du Cuvry Conception graphique : Alain BEHR Consultant - 2014 Photos Maupas Verny Verny Verny D66 N 431 de Fey D913 Ruisseau D5 Canal D5a vers A31 D66 Fossé BALISAGE VTT Bois la Dame L'itinéraire est balisé dans les deux sens. -

Gare De Metz-Nord

Mai 2017 Valoriser et (re)composerCOTAM les espaces Gare Gare de Metz-Nord ommaire 1 Préambule 4 2 Un quartier du cœur d’agglomération 6 3 La gare au sein du réseau ferroviaire régional 7 4 Structuration urbaine et paysagère du quartier gare 13 5 Potentiels de mutation et projets 16 Intermodalité du quartier gare 18 En partenariat avec 6 7 Enjeux et Préconisations 22 ommaire 1 Préambule 4 Contexte de l’étude Objectifs 2 Metz-Nord, un quartier du cœur d’agglomération 6 Un pôle urbain d’équilibre en appui du cœur d’agglomération 3 La gare de Metz-Nord au sein du réseau ferroviaire régional 7 Une aire d’attraction restreinte à Metz ? Une offre cadencée revue à la hausse Attractivité de l’offre Usages connus et implications concernant les conditions d’accès à la gare 4 Structuration urbaine et paysagère du quartier gare 13 Cadrage communal Un quartier gare diversifié sans polarité forte Un développement urbain contraint à la mutation existant Un secteur gare fortement urbanisé avec une présence végétale concentrée au nord 5 Potentiels de mutation et projets 16 Un potentiel de densification fortement restreint 6 Intermodalité du quartier gare 18 Une bonne accessibilité routière Une offre de stationnement saturée Le Met’ : une desserte en trompe l’œil Modes doux : des bases à conforter ? Synthèse et enjeux 7 Enjeux et Préconisations 22 Mobilité Densité et potentiel foncier Fonctions urbaines Cadre urbain et paysager Espaces publics Préambule / Contexte de l’étude A travers son DOO (document d’orientation et d’objectifs), le SCoTAM préconise (cible 5.2 et 9.4) l’amélioration de l’accessibilité à l’offre de transports en commun et une meilleure cohérence entre politiques de transport et d’urbanisme. -

24 - 31 Mar S 2020

24 - 31 MAR S 2020 PROJECTIONS DE COURTS MÉTRAGES PROG R AMME MCL RENCONTRES - ATELIERS - EXPOSITIONS METZ CINÉMAS ET LIEUX CULTURELS DE METZ METZ VILLE AMBASSADRICE PARMI 35 VILLES FRANÇAISES La Fête du court métrage à l’initiative de l’association Faites des Courts, Fête des Films est un évènement d’envergure nationale et internationale qui vise à promouvoir auprès de tous le court-métrage sous toutes ses formes. Chaque année en France, ce sont plus de 12 500 séances de projections organisées dans 3 300 communes participantes en France et à l’étranger. Depuis 2016, l’association Cycl-One organise La Fête du court métrage à Metz et en Région Grand Est, en partenariat avec de nombreux acteurs associatifs locaux. Soutenus par la coordination nationale, nous avons l’honneur, depuis 2019, de représenter Metz en tant que Ville Ambassadrice de La Fête du court métrage parmi 35 autres villes sélectionnées en France. Notre objectif à travers cet évènement est de permettre l’accès à la culture pour tous et de fédérer des publics autour du court-métrage à travers un évènement accessible à tous, convivial et gratuit. Vous y découvrirez toute la richesse du film court, de fiction d’animation ou documentaire à travers une programmation plurielle. Nous vous invitons à rencontrer des réalisateurs et réalisatrices, à participer à des ateliers et à découvrir des expositions. INAUGURATION MCL METZ à partir de 12 ans Mardi 24 mars - 18h30 Projection du film POLLUX en présence du comédien Tom-Elliot Fosse-Taurel SÉANCE SPÉCIALE ARTE - TU MOURRAS MOINS BÊTE -

Sarreguemines, Le 24 Novembre 2015

SYNDICAT MIXTE DE L’ARRONDISSEMENT DE SARREGUEMINES PAYS – LEADER – SCOT – SIG RAPPORT D’ACTIVITE DE L’ANNEE 2019 Rapport d’activité SMAS 2019 1/66 SYNDICAT MIXTE DE L’ARRONDISSEMENT DE SARREGUEMINES PAYS – LEADER – SCOT – SIG Table des matières SUIVI DES PROJETS DE PAYS 4 POURSUITE DE L’ACCOMPAGNEMENT DU CONSEIL DE DEVELOPPEMENT DU PAYS DE SARREGUEMINES BITCHE 4 COORDINATION DE L’ESPACE INFO ENERGIE MOSELLE EST POUR LE PAYS DE L’ARRONDISSEMENT DE SARREGUEMINES 8 DISPOSITIF DE PREVENTION DES JEUNES DECROCHEURS « SOUTIEN ACCOMPAGNEMENT APPUI » 9 DEMARCHE DE RELOCALISATION DE PRODUITS LOCAUX 9 PARTICIPATION AUX RESEAUX « PAYS » ET AUX DEMARCHES PARTENARIALES 11 SYSTEME D’INFORMATION GEOGRAPHIQUE (SIG) 12 FORMATION / ACCOMPAGNEMENT DES UTILISATEURS SIG 12 LEVES PHOTOGRAPHIQUES PAR DRONE 13 MISE A JOUR GRAPHIQUE DES PLANS DE CONCESSIONS DE CIMETIERE 14 INTEGRATION DE RESEAUX D’ASSAINISSEMENT 16 PRODUCTION DE CARTOGRAPHIES 16 EVALUATION DU SCOT 19 SCOT ET URBANISME 21 MISE EN ŒUVRE DU SCOT ET ACCOMPAGNEMENT DES COMMUNES ET EPCI 21 EVALUATION DU SCOT A 6 ANS 21 SCOT ET AMENAGEMENT COMMERCIAL 22 PARTICIPATION AUX REFLEXIONS NATIONALES SUR L’OBSERVATION COMMERCIALE 23 CONTRIBUTIONS AU SRADDET 23 RESEAUX ET PARTENARIATS 24 PROGRAMME LEADER 26 ANIMATION/ COMMUNICATION 26 EVALUATION CROISEE A MI-PARCOURS DU PROGRAMME EUROPEEN LEADER DU GAL DU PAYS DE L’ARRONDISSEMENT DE SARREGUEMINES ET DU GAL DES VOSGES DU NORD 28 ACCOMPAGNEMENT D’INITIATIVES PRIVEES ET PUBLIQUES DANS LA RECHERCHE DE FINANCEMENTS 31 COMITES DE PROGRAMMATION 32 ENVELOPPE COMPLEMENTAIRE -

Alsace Waterways Guide

V O L 1 . 1 F R E E D O W N L O A D discover Sharing our love for France's spectacular waterways Alsace Beautiful canalside towns, exceptional wines & fresh produce, complex history, Art Nouveau, Vosges mountains, Nancy & Metz P A G E 2 Afloat in Alsace YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE PERFECT CANAL CRUISE Why Alsace? Being so close to the German border, Alsace has an interesting mix of Scenery & climate French and German influences. The magnificence of the rolling History landscape can leave some awestruck and certainly snap-happy with Local produce & climate their cameras. The Marne-Rhine canal is the focus for hotel barging as it Wine steers you towards Alsace Lorraine's beautiful towns and cities like Marne Rhine Canal stunning Colmar, and to the flavours of Alsace in flammekueche, Canal des Vosges Riesling and Gewurtztraminer. It's a region that continues to surprise When to go and delight us, we hope it sparks a fondness for you too. How to cruise Ruth & the team Contact us P A G E 3 WHY ALSACE? Because it’s not as well-known as the Canal du Bourgogne or the Canal du Midi, but every bit as beautiful? Because it’s within easy reach of two marvellous French cities – Nancy and Metz? Or is it because it’s a focal point of European history during the last 150 years? Or perhaps for its Art Nouveau or flammekueche? The list of attractions is long. Directly east of Paris, the region of Alsace Lorraine is bordered by the Vosges mountains to the west and the Jura to the south, while boasting plains and wetlands as well, creating striking contrasts which make it an extremely photogenic place to visit. -

CENTRE HOSPITALIER REGIONAL De METZ THIONVILLE

CENTRE HOSPITALIER REGIONAL de METZ THIONVILLE Directeur Général : Patrick GUILLOT [email protected] Vice-Président de la Commission Médicale d’Etablissement : Dr Khalifé KHALIFE k.khalifé@chr-metz-thionville.rss.fr Président de la Commission Médicale d’Etablissement : Dr Michel BEMER [email protected] Service de communication : Chargée de Communication Groupement des Hôpitaux de Thionville : Corinne ROLDO 03 82 55 80 09 - Fax : 03 82 55 88 23 [email protected] Adresse :Direction Générale Chargée de Communication Groupement 28-32 Rue du XX°Corps Américain des Hôpitaux de Metz : BP 770 - 57019 Metz cedex 1 Véronique DEFLORAINE 03 87 66 73 76 03 87 55 79 04 - Fax : 03 87 55 39 88 Fax : 03 87 55 39 88 [email protected] CENTRE HOSPITALIER REGIONAL DE METZ THIONVILLE La Lorraine La situation démographique en Lorraine est désormais stabilisée. Les bassins de Metz et de Thionville enregistrent même une augmentation du nombre d’habitants. Par contre, les indicateurs épidémiologiques demeurent peu favorables. Les 3 premières causes de surmortalité sont les maladies cardio-vasculaires, les tumeurs et les morts violentes. Les facteurs de risques ont été identifiés : circulation, conduites addictives, nutrition et hygiène de vie. Enfin, la présence de nombreux établissements privés participant au service public dans la zone d’attraction du CHR constitue une particularité hospitalière locale. Le CHR de Metz-Thionville dans le système sanitaire régional Le CHR : un ensemble hospitalier réparti sur 2 villes différentes, distantes de 30 km, sur 2 bassins de santé distincts ne peut être conçu de la même façon qu’un hôpital situé dans une agglomération unique. -

ELECTIONS MUNICIPALES 1Er Tour Du 15 Mars 2020

ELECTIONS MUNICIPALES 1er tour du 15 Mars 2020 Livre des candidats par commune (scrutin plurinominal) (limité aux communes du portefeuille : Arrondissement de Sarreguemines) Page 1 Elections Municipales 1er tour du 15 Mars 2020 Candidats au scrutin plurinominal majoritaire Commune : Baerenthal (Moselle) Nombre de sièges à pourvoir : 15 Mme BLANALT Martine M. BRUCKER Samuel M. BRUNNER Pierre Mme CHARPENTIER Julie M. CROPSAL Christian M. DEVIN Serge M. FISCHER Yannick M. GUEHL Vincent M. HOEHR Freddy Mme KOSCHER Catherine Mme LEVAVASSEUR Aurélie Mme SCHUBEL Nicole M. WEIL Serge M. WOLF Cédric Mme ZUGMEYER Martine Page 2 Elections Municipales 1er tour du 15 Mars 2020 Candidats au scrutin plurinominal majoritaire Commune : Bettviller (Moselle) Nombre de sièges à pourvoir : 15 M. BECK Laurent Mme BEHR Cindy M. BLAISE Philippe Mme BRECKO Laetitia Mme FALCK Sandrine M. FIERLING Michaël M. GUEDE Teddy Mme HEINTZ Nelly M. HERRMANN Didier M. HERRMANN Fabien M. KIFFER Marc M. MARTZEL Christophe Mme MEYER Cindy M. MEYER Cyrille M. MIKELBRENCIS Jean-Michel M. MULLER Stéphan Mme OBER Nadia M. RITTIÉ Arnaud M. SCHAEFER Raphaël M. SCHNEIDER Manoël M. SCHNEIDER Marc M. SPRUNCK Manuel Mme STEYER Elisabeth M. THOMAS Christian Mme WAGNER Catherine M. WEBER Emmanuel M. WEBER Michel Mme WEISS Cathy Mme WEISS Elisabeth M. ZINS Emmanuel Page 3 Elections Municipales 1er tour du 15 Mars 2020 Candidats au scrutin plurinominal majoritaire Commune : Blies-Ebersing (Moselle) Nombre de sièges à pourvoir : 15 Mme BEINSTEINER Bernadette M. BOUR Thierry M. DELLINGER Frédéric Mme DEMOULIN Mireille Mme HERTER Marie Christine Mme HEUSINGER-LAHN Monika (Nationalité : Allemande) Mme HOLZHAMMER Murielle M. JOLY Sébastien M. -

Cercle De Metz-Campagne

ARCHIVES DEPARTEMENTALES de la MOSELLE 14 Z - Direction de cercle de Metz-Campagne. Le cercle de Metz est l'héritier de l'arrondissement créé pour le sous-préfet allemand installé à Faulquemont pendant le siège de Metz (ordre de cabinet du roi de Prusse du 21 août 1870) ; amputé de l'administration du territoire communal de Metz, des cantons de Boulay et de Faulquemont (ordonnance du 12 mars 1871) et de 12 communes de l'ancien canton de Gorze, le cercle s'étendit des 7 communes de l'arrondissement de Briey cédées à l'empire allemand en vertu du traité de Francfort. Fonds versé en 1935 après la suppression de la sous-préfecture de Metz-Campagne et conservé dans son intégralité. 14Z1 - 14Z22/3 Cabinet. 14Z1 Lois, décrets, publications officielles (1886-1918). Avis des autorités militaires (1915-1918). "Nouvelles officielles pour l'arrondissement" (1904-1918). 1886 - 1918 14Z2 "Amtliche Nachrichten für den Landkreis Metz" (1916-1918). 1906 - 1918 14Z3 Autorités (1887-1917). Emploi de la langue française (1915-1918). Germanisation des noms des communes (1915-1918). 1887 - 1918 14Z4 Fonctionnaires de l'Etat (1887-1917). Secours Alsweh (1910-1918). 1887 - 1918 14Z5 Employés de la direction de cercle. 1872 - 1918 14Z6 Bâtiment de la direction de cercle. Frais de bureau. 1893 - 1906 14Z7 Délimitation de l'arrondissement (1870-1913). Frontières (1877-1917). Triangulation (1874-1914). 1870 - 1914 14Z8 Elections, instructions (1882-1914). Listes électorales (1881-1915). Elections au conseil général et au conseil d'arrondissement (1905-1911). Elections au Landtag d'Alsace-Lorraine (1911-1912). 1881 - 1915 14Z9 Elections au Reichstag (1895-1912). -

Remise Du Chèque National De L'association Une Rose, Un Espoir D'un Montant De 1 561 083,40 € Le 08 Juillet Dernier À Ro

N° 02/2017 Remise du chèque national de l’Association Une Rose, Un Espoir d’un montant de 1 561 083,40 € le 08 juillet dernier à Rohrbach-lès-Bitche. La section Du Bitcherland à elle seule, a récolté 75 000 € Mesdames, Messieurs, chers concitoyens, Si l’été s’est bel et bien installé durant cette période estivale, ce dont nous nous réjouissons toutes et tous, soyons malgré tout vigilants face aux températures caniculaires qui sont parfois difficiles à supporter par nos concitoyens fragiles et souffrants et en tant que voisins de personnes seules et âgées soyons attentifs et assurons-nous de leur bien-être. Ce bulletin présente une page consacrée au budget de la commune qui mérite un commentaire particulier tant sur le volume des investissements prévus en dépenses qu’au niveau des recettes de fonctionnement dont les impôts locaux ont été relevés de l’ordre de 2 %. Il est vrai que depuis plus de 30 ans les taux d’imposition dans les budgets successifs n’ont jamais été modifiés. Aujourd’hui les réalités sont différentes. Le contexte général des finances publiques a évolué mais pas dans le bon sens du terme. On demande aux collectivités territoriales et notamment aux communes de participer au redressement des finances publiques pour freiner le déficit public de l’Etat. C’est chose faite car d’une année sur l’autre nous perdons environ 6.000 à 7.000 € de dotations de l’Etat alors que les dépenses obligatoires augmentent. Comment alors se constituer des réserves pour permettre le financement des projets communaux indispensables pour le bien être des habitants.