Cultural Disjuncture in the European Union: a Narrative Approach to Integration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

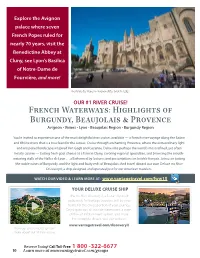

French Waterways: Highlights of Burgundy, Beaujolais & Provence

Explore the Avignon palace where seven French Popes ruled for nearly 70 years, visit the Benedictine Abbey at Cluny, see Lyon’s Basilica of Notre-Dame de Fourvière, and more! The Palais des Popes in Avignon dates back to 1252. OUR #1 RIVER CRUISE! French Waterways: Highlights of Burgundy, Beaujolais & Provence Avignon • Viviers • Lyon • Beaujolais Region • Burgundy Region You’re invited to experience one of the most delightful river cruises available — a French river voyage along the Saône and Rhône rivers that is a true feast for the senses. Cruise through enchanting Provence, where the extraordinary light and unspoiled landscapes inspired Van Gogh and Cezanne. Delve into perhaps the world’s most refined, yet often hearty cuisine — tasting fresh goat cheese at a farm in Cluny, savoring regional specialties, and browsing the mouth- watering stalls of the Halles de Lyon . all informed by lectures and presentations on la table français. Join us in tasting the noble wines of Burgundy, and the light and fruity reds of Beaujolais. And travel aboard our own Deluxe ms River Discovery II, a ship designed and operated just for our American travelers. WATCH OUR VIDEO & LEARN MORE AT: www.vantagetravel.com/fww15 Additional Online Content YOUR DELUXE CRUISE SHIP Facebook The ms River Discovery II, a 5-star ship built exclusively for Vantage travelers, will be your home for the cruise portion of your journey. Enjoy spacious, all outside staterooms, a state- of-the-art infotainment system, and more. For complete details, visit our website. www.vantagetravel.com/discoveryII View our online video to learn more about our #1 river cruise. -

Sedgwick Opens New Offices in Corsica, Gap and Guadeloupe, to Further Expand Its Operations in France and in French Overseas Territory

Sedgwick opens new offices in Corsica, Gap and Guadeloupe, to further expand its operations in France and in French overseas territory PARIS, 19 February 2021 – Sedgwick, a leading global provider of technology-enabled risk, benefits and integrated business solutions, today announced the opening of three new offices in Corsica and Gap, southern France and in Guadeloupe, French overseas department and region. This expansion will increase the company’s capacity to assist the evolving needs of existing and future clients in various parts of France and the overseas departments and regions and build on its growing market presence. The new offices will increase Sedgwick’s footprint and meet the growing demand for specialist claims and loss adjusting solutions in France and the overseas departments in the Caribbean. Sedgwick also plans to continue recruiting and expanding local teams in various parts of France in order to capitalize on this significant market opportunity. The combination of a national network, highly performant digital tools and local experts will present clients with better tailored solutions and well adapted to any specific given event. In the coming months, Sedgwick aims to open several more offices as part of its overall strategic plan to expand its footprint, as well as to increase proximity with clients and their policyholders. As such, there are plans to launch several new offices in 2021, in Metropolitan France and Monaco. Xavier Gazay, president and director general of Sedgwick in France said: “The opening of our new offices in Corsica, Gap and Guadeloupe is another indicator of the momentum we are building to maximize the country’s growth opportunities. -

Colors of Provence Cruising the Rhône with Amawaterways

October 21–31, 2019 Colors of Provence Cruising the Rhône with AmaWaterways Join Mary Gaffney-Ward and fellow Madison Club members on a magical French culinary and wine adventure. Our cruise begins in Arles, Provence, a city of Roman treasures, in one of the world’s great wine regions. We travel the Rhône River in luxury aboard the AmaCello for on our journey to the French culinary capital, the UNESCO Heritage city of Lyon. A journey of French wine & culinary delights From romantic cities to foodie havens and artistic epicenters, our itinerary features will enliven the senses. We’ll trace the steps of Van Gogh in Arles, discover the Carriéres de Lumiéres, savor the beauty of legendary vineyards and enjoy local vintages Beaujolais and Côtes du Rhône. We’ll go in search of the highly prized “Black $3497* Madison Club member price Diamond” truffles, learn to pair chocolate with wines and per participant double occupancy stateroom discover how olives became the Mediterranean’s nector, olive oil. We’ll cap our adventure in France’s culinary PUBLISHED PRICE $4798 capital, Lyon. *Pre-cruise, port charges & airfare additional *Early bird pricing--must book before Feburary 20 2019 Your $700 deposit per person secures one of our fourteen staterooms. KARL GUTKNECHT | 608/345.6557 [email protected] Colors of Provence The Rhône River Besides providing captivating views of medieval towns and colorful landscapes, the Rhône River connects the dots between thousands of vineyards from Lyon to Avignon. Our Colors of Provence itinerary takes you through this prized wine-producing region in southeastern France, known across the globe as the Rhône Valley. -

Cultural Start-Up Award” Presented at the Forum D’Avignon@Bordeaux 2016

The Forum d’Avignon's “Cultural Start-up Award” presented at the Forum d’Avignon@Bordeaux 2016 Terms and conditions Preamble The future is fueled by talent. Since its creation in 2007, the Forum d'Avignon has fostered through its works and commitments the emergence of a new generation of cultural and creative entrepreneurs. The Forum d'Avignon is convinced that the encounter between both artistic and entrepreneurial cultures has always been fruitful—from the mill to the workshop, from the studio to the factory. The Forum d'Avignon has chosen this year to highlight the best achievements and the most innovative projects in the field of cultural entrepreneurship by bestowing the Cultural Start-up Award to projects that combine a solid business model while promoting cultural diversity. Article 1: The organizing entity The Forum d’Avignon, a non-profit association registered in Paris, is located at the Grand Palais des Champs Elysées – Cours la reine – Porte C – 75008. The Forum d’Avignon is organizing the Cultural Start-up Award from December 15 through March 28, 2016. Article 2: Purpose The Cultural Start-up Award is organized by the Forum d'Avignon and will be presented at the Forum d'Avignon @Bordeaux. It aims at rewarding the best achievements and the most innovative projects in the field of cultural entrepreneurship, projects that combine a solid business model while promoting cultural diversity. The Cultural Start-up Award is divided into two categories: 1. “Jury Prize” 2. “Public Prize” Article 3: Agenda - December 15, 2015: Launch of the call for applications - February 15, 2016, midnight: Deadline for application submissions - March 8, 2016: Votes open for the winner of the “Public Prize” among the five shortlisted candidates - March 28, 2016: End of votes for the “Public Prize” - March 31, 2016: the award ceremony of the The Cultural Start-up Award is to take place during the opening sessions of the Forum d’Avignon @Bordeaux. -

LA DRÔME EN 12 ITINÉRAIRES 12 Itineraries in the Drôme

LA DRÔME EN 12 ITINÉRAIRES 12 itineraries in the Drôme ladrometourisme.com Entre la Drôme et vous, une belle histoire commence… Cette histoire pourrait démarrer comme ceci : « Il était une fois 12 itinéraires à suivre pour découvrir les incontournables de cette terre de contrastes. Prenez le temps d’apprécier le paysage, d’échanger avec les habitants, de flâner dans les villes et villages, de visiter les monuments et musées incontournables (Palais Idéal du Facteur Cheval, Tour de Crest, châteaux de Montélimar, Grignan et Suze-la-Rousse, cité du chocolat Valrhona Musée International de la chaussure…), de savourer les produits du terroir de la Drôme, à la ferme, au détour des routes thématiques (lavande, olivier, vin…) ou sur les marchés colorés, de pratiquer toutes sortes d’activités sportives dont la randonnée pédestre, équestre, en raquettes, le ski, le vélo, le VTT, l’escalade, la via ferrata... … la Drôme vous livrera ses plus beaux secrets à travers ses paysages les plus sauvages. » La morale de cette histoire : Faîtes une pause dans la Drôme pour la découvrir plus intimement. Champ de lavande • Poët-Sigillat Between the Drôme and you, a wonderful story-line may emerge. The story could start like this: Vous aussi devenez fan de « Once upon a time there were 12 itineraries to follow to discover the key features of this land of contrasts. Take the time to appreciate the landscape, to have a chat with local people, to stroll about the towns and villages, la page Facebook de la Drôme to visit the main monuments and museums (‘Palais Idéal du Facteur Cheval’, Crest tower, the châteaux of Tourisme et racontez Montélimar, Grignan and Suze-la-Rousse, ‘cité du chocolat Valrhona’ and the ‘Musée International de la vos vacances dans la Drôme Chaussure [shoes]), to taste the products of the Drôme at the farm itself, along the themed routes (lavender, olives, wines …), on the colourful markets, to practice all kinds of sporting activity including walking, riding, rackets, skiing, cycling, mountain-biking, climbing, the via ferrata, etc. -

Bilan De La Saison Pollinique PACA 2017

Bilan de la saison pollinique PROVENCE-ALPES- CÔTE D’AZUR et CORSE Année 2017 RNSA Le Plat du Pin 69690 BRUSSIEU Tel 04 74 26 19 48 – Fax : 04 74 26 16 33 Mail [email protected] Internet www.pollens.fr Table des matières Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Capteurs de pollens en région PACA ................................................................................................................ 2 Taux de fonctionnement des capteurs ............................................................................................................ 6 Résultats principaux de l’année 2017 pour la région PACA (+ Corse) ............................................................. 7 Pollens d’arbres .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Pollens de Frêne ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Pollens de Cyprès ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Pollens de Chêne .......................................................................................................................................... 10 Pollens de Platane ....................................................................................................................................... -

Paris in the Spring, Burgundy & Provence

Exclusive Charter NBSAC presents Paris in the Spring, Burgundy & Provence River Cruise featuring 2 Nights in Paris & 7 nights aboard the Amadeus Provence 11 Days April 13 - April 23, 2020 Booking Discount - Save $200 per couple! Daily Itinerary Cities & Ports Paris in the Spring, Burgundy & Provence River Cruise Paris Enjoy a panoramic Paris City Tour, the “City of Light,” to see the beloved land- 11 Days April 13 - 23, 2020 Ship - Amadeus Provence marks of Paris that line the Seine including the grand Notre Dame Cathedral and the palatial façade of the Louvre. The river’s historic banks are a UNESCO World Day 1 Depart US - Overnight Flight Heritage Site. Enjoy an afternoon of leisure time to admire the masterpieces of Day 2 Arrive Paris the Louvre or ascend the Eiffel Tower for fantastic views. Meet your PWD Tour/Cruise Manager - Transfer to your hotel for 2-Night Stay Dijon Welcome Drink at the hotel Overnight - Paris Enroute from Paris to your ship, stop for a Dijon Walking Tour. Best known for its Day 3 Paris mustard, Dijon is also one of the most beautiful cities in France with a wonder- Morning Paris City Tour ful historical center registered as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Dijon mustard Afternoon at leisure or Optional Excursion to Versailles originated in 1856, when Jean Naigeon substituted, the acidic juice of not-ripe Meal - B Overnight - Paris grapes, for vinegar in the traditional mustard recipe. Day 4 Paris - Dijon - Lyon Lyon Travel to Dijon via motorcoach and enjoy a Dijon Walking Tour Lyon, a city in France’s historical Rhône-Alpes region, sits at the junction of the Continue to Lyon and board the MS Amadeus Provence for 7 nights Rhône & Saône Rivers with a history dating back to ancient Roman times. -

Francja Edit Nancy Thompson

‘Inspired by the Impressionists’ Provence Tour Art League of Ocean City June 14-24, 2020 with Nancy Ellen Thompson Experience Magical Provence A journey you will never forget! Join us! Lavender, vineyards, olive trees, thyme, fresh figs, medieval villages, markets and sun-filled landscapes! Discover why the region was such an inspiration for artists like Van Gogh, Picasso, Cezanne and Monet. Following in the footsteps of the Impressionists in Provence, we will visit many important and beautiful towns and villages: -St Remy where Vincent Van Gogh spent the last months of his life. We will visit Saint-Paul-de-Mausole monastery, the hospice where the painter produced some of his most famous works, such as the Sunflowers. -Aix-en-Provence, a thriving cultural center. Here we will visit Cézanne’s studio, left just as it was when he painted there. -Arles , a Provencal city called Little Rome. Centuries ago, it played an important role as a colony of Julius Caesar and today is a great museum of a city. This is the city where Vincent van Gogh created his most important paintings and lost his ear. Also, Picasso and his museum, to which Picasso, in love with Arles and in bullfights, donated a number of his works and thus initiated the creation of a museum of the art of his own name. June is lavender season! We will sketch beautiful fields and visit the lavender museum in Senanqe Abbey. It is one of the most photographic places in France. Of course, we make time to explore vineyards and have a wine tasting of French wines. -

Whatismodernart.Pdf

Many artists explored dreams, symbolism, and personal iconography as ways to depict their experiences. • Cézanne captures a sense of emotional ambiguity or uncertainty in The Bather that could be considered typical of the modern experience. 3a. Look at the figure. What do you notice about his stance and gaze? 3b. Do you think Cézanne painted from real life or from a photograph? (another modern technique) Paul Cézanne. The Bather. c. 1885. Modern artists also experimented with the expressive use of color, non-traditional materials, and new techniques and mediums. 4a. What do you notice about the figures and the setting? Do the fractured planes make the setting difficult to identify? 4b.What else do you think is ‘modern’ about this picture? 4c.What do you see in this work. 4d.Describe the figures’ body lfilidlanguage, facial expressions, and relationships to each other. Pablo Picasso . Les Demoiselles d'Avignon . Paris, June-July 1907 Modern artists also expressed the symbolic, by depicting scenes and places that evoked an inner mood rather than a realistic landscape. Van Gogh’s landscape might be considered Symbolist because its imagery is evoking an inner mood rather than a realistic landscape. (Symbolism rejects traditional iconography and replaces it with subjects that express ideas beyond the literal objects depicted.) 5a. What might the shimmering stdiliihttars, moon, and swirling night air symbolize to Van Gogh? 5b. What mood or feelinggy do you think van Gogh was trying to convey? Vincent van Gogh. The Starry Night. June 1889 The invention of photography in the 1830’s introduced a new method for depicting and reinterpreting the world. -

Avignon Vs. Rome: Dante, Petrarch, Catherine of Siena

[Expositions 4.1&2 (2010) 47-62] Expositions (online) ISSN: 1747-5376 Avignon vs. Rome: Dante, Petrarch, Catherine of Siena THOMAS RENNA Saginaw Valley State University ABSTRACT In the fourteenth century the image of ancient Rome as Babylon was transformed into the positive idea of Rome as both a Christian and a classical ideal. Whereas Dante disassociated Augustine‟s Babylon from imperial Rome, Petrarch turned Avignon into Babylon, a symbol of an avaricious papacy. For Catherine of Siena Avignon was not evil, but a distraction which prevented the pope from reforming the Italian clergy, bringing peace to Italy, and launching the crusade. “There is only one hope of salvation in this place! Here, Christ is sold for gold!”1 And so Francesco Petrarch denounced the Avignon of the popes as the most evil place on earth since the days of ancient Babylon. This view of the Holy See should have disappeared when the papacy returned to Rome in 1377, but it did not. On the contrary, the castigation of the sins of pontiffs intensified, as subsequent ages used this profile to vilify the papacy, the clergy, the French monarchy, and the French nation.2 Not to be outdone, some French historians in the twentieth century sought to correct this received tradition by examining the popes‟ worthy qualities.3 It is curious that this depiction of Avignon as the Babylon Captivity has enjoyed such longevity, even in college textbooks.4 “Corruption” is of course a value judgment as much as a description of actual behavior. Doubtless Pope Clement VI did not think of his curia as “corrupt.” Contemporary citizens of Mongolia do not see Genghis Khan as the monster of the medieval Christian chronicles. -

Trade Cover 1

Trade cover 1 BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 91BMD1467900.pgs 11.09.2014 16:48 IFC BELMOND IS A WORLDWIDE COLLECTION OF ICONIC HOTELS, TRAINS AND RIVER CRUISES. MASTERS OF THE ART OF HOSPITALITY, WE BRING OUTSTANDING EXPERTISE TO GREAT JOURNEYS, CELEBRATORY OCCASIONS AND BUSINESS MEETINGS OF EVERY KIND. HOTELS | TRAINS | RIVER CRUISES | JOURNEYS BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 91BMD1467908.pgs 11.09.2014 18:21 Hero image BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 91BMD1417100.pgs 09.09.2014 15:59 BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN Chapter opener 91BMD1417101.pgs 11.08.2014 10:46 belmond.com BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN CRUISING AT Magical France YOUR LEISURE Explore some of the most enchanting regions of France from its great waterways. Enjoying all the comforts of a luxury barge, you drift past vineyards and felds of lavender to visit châteaux and tour vibrant towns. he majestic vineyards of Burgundy, the T medieval villages of Provence… All of this is yours to explore with Belmond Afoat in France, a feet of fve luxury barges that drifts along the country’s rivers and canals. This is cruising that allows the connoisseur to appreciate the beauty and culture of the French waterways to the full. On board you are offered every indulgence, from plunge pools to the fnest cuisine; on land you can enjoy exclusive wine tastings and fascinating excursions. Whether you seek a family holiday, reunion with friends or a romantic escape, or perhaps share an interest in golf or photography, we can create the perfect journey with customised itineraries to realise your dreams. Cruise along at your own pace and discover France’s remarkable landscapes, welcoming people and delicious food and wine. -

PARIS, PROVENCE & FRENCH RIVIERA Paris - Avignon - Nice 1 Paris Arrival in Paris

PARIS, PROVENCE & FRENCH RIVIERA Paris - Avignon - Nice 1 Paris Arrival in Paris. After check-in at your hotel, the balance of the day is at leisure to explore Paris, the magnificent capital Paris of France. Packed with monuments, 2 Your included morning city tour features the Arc de museums, art, nightlife, eateries and Triomphe, Opera House, Champs-Elysees, Notre shops, Paris remains - in spite of all the Dame Cathedral and much more. There is so much to cliches - one of the most inspiring cities in see and do in Paris, a city so aptly called the City of the world. Lights, where exciting evening outings are a must. Paris 3 Full day at leisure to enjoy the warmth and charm of a traditional French bistro or to take an optional excursion to Versailles. Paris/Avignon Today travel by rail from Paris to 4 Avignon, a UNESCO World Heritage Avignon Site. The afternoon is at leisure. After breakfast, enjoy a visit of the Popes' Wander the narrow streets to discover Palace, the largest Gothic palace in the this interesting town full of history, life world. In the afternoon enjoy a one hour and art. cruise on the Rhone River, before ending the day with a nice dinner in a popular Avignon/Nice 5 restaurant. This morning, board your train to Nice. Located in the heart of one of the world's most highly prized regions, it offers a rich history and a wonderfully mild sunny climate. Check-in at your hotel. 6 7 Nice Full day at leisure to visit, on your own, the many outdoor markets, parks and beautiful museums this lovely city has to offer.