Embry-Rifldle Aeronautical University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crew Escape Systems 21002

USA009026 Basic Space Flight Operations Contract Crew Escape Systems 21002 January 17, 2005 Contract NAS9-20000 USA009026 Basic Crew Escape Systems 21002 Prepared by Original signature obtained J. Lynn Coldiron, Book Manager USA/Crew Escape Approved by Original signature obtained Adam Flagan, Escape Technical Lead USA/Crew Systems Group Lead Original signature obtained M. Jude Alexander, Lead USA/Photo/TV/Crew Systems Group Contract NAS9-20000 USA009026 Basic REVISION LOG Rev. Change Description Date letter no. Basic Supersedes SFOC-FL0236 01/17/2005 USA009026 Basic LIST OF EFFECTIVE PAGES The status of all pages in this document is shown below: Page No. Change No. i – vi Basic 1-1 – 1-2 Basic 2-1 – 2-41 Basic 3-1 – 3-41 Basic 4-1 – 4-5 Basic 5-1 – 5-45 Basic A-1 – A-3 Basic B-1 – B-3 Basic USA009026 Basic PREFACE This document was prepared by the United Space Alliance under contract to the Mechanical, Booster, and Maintenance Systems Branch, Systems Division, NASA, Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas. Documentation support was provided by Hernandez Engineering, Inc., Space Flight Operations Contract (HEI-SFOC). Information contained in this document is provided for the use and training of crewmembers and for use by escape instructors and others who need to know about equipment, systems, and procedures relating to orbiter emergency egress and crew rescue. The document describes and explains the use of crew-worn equipment and orbiter hardware. It also identifies the escape modes and the orbiter crew response in each mode. It is intended to be a workbook to which notes and additional information presented in classroom sessions can be added. -

Aircraft Procurement Volume II, Part 1

Committee Staff Procurement Backup Book FY 2005 Budget Estimates February 2004 AIRCRAFT PROCUREMENT, AIR FORCE VOLUME II OPR: SAF/FMB UNCLASSIFIED Table of Contents FY 2005 AMENDED PRESIDENT'S BUDGET AIRCRAFT PROCUREMENT MODIFICATIONS, AIR FORCE Section 1: P-1M Modification Summary. 1 Section 2: P-1 Line Item Detail . 47 STRATEGIC AIRCRAFT 21 B-2. 47 22 B-1. 75 23 B-52. 99 24 F-117 . 119 TACTICAL AIRCRAFT 25 A-10. 129 26 F-15 . 143 27 F-16 . 189 28 F-22 . 255 29 A/T-37 . 267 AIRLIFT AIRCRAFT 30 C-5. 269 31 C-9. 283 32 C-17. 285 33 C-21. 313 34 C-32. 319 35 C-37. 325 36 C-141. 327 TRAINER AIRCRAFT 37 T-6 . 329 38 T-38 . 337 39 T-41 . 349 40 T-43 . 351 i UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED OTHER AIRCRAFT 41 KC-10 . 357 42 C-12. 369 43 C-18. 373 44 C-20. 375 45 C-25. 379 46 C-40. 389 47 C-130. 391 48 C-130J . 461 49 C-135. 469 50 C-29. 489 52 E-3 . 493 53 E-4 . 511 54 E-8C . 531 55 H-1. 541 56 HH-60 . 551 57 OTHER . 569 58 PRDT. 589 59 CV-22 . 597 60 CLASSI . 599 51 DARP . 603 ii UNCLASSIFIED ***UNCLASSIFIED. -

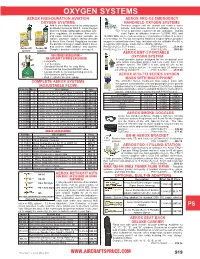

Oxygen Systems

OXYGEN SYSTEMS AEROX HIGH-DURATION AVIATION AEROX PRO-O2 EMERGENCY OXYGEN SYSTEMS HANDHELD OXYGEN SYSTEMS Add to your flying comfort by using oxygen Provides oxygen until the aircraft can reach a lower at altitudes as low as 5000 ft. Aerox Oxygen altitude. And because Pro-O2 is refillable, there is no CM Systems include lightweight aluminum cyl in- need to purchase replacement O2 cartridges. During ders, regulators, all hardware, flow meter, short flights at altitudes between 12,500ft. MSL and and nasal cannulas (masks available as 14,000ft. MSL where maneuvering over mountains or turbulent weather option). Oxysaver oxygen saving cannulas is necessary, the Pro-O2 emergency handheld oxygen system provides & Aerox Flow Control Regulators increase oxygen to extend these brief legs. Included with the refillable Pro-O2 is WP the duration of oxygen supply about 4 times, a regulator with gauge, mask and a refillable cylinder. and prevent nasal irritation and dryness. Pro-O2-2 (2 Cu. Ft./1 mask)........................P/N 13-02735 .........$328.00 Aerox 2D Aerox 4M Complete brochure available on request. Pro-O2-4 (2 Cu. Ft./2 masks) ......................P/N 13-02736 .........$360.00 system system AEROX EMT-3 PORTABLE 500 SERIES REGULATOR – AN AIRCRAFT SPRUCE EXCLUSIVE! OXYGEN SYSTEM ME A small portable system designed for the occasional user • Low profile who wants something smaller and less costly than a full • 1, 2, & 4 place portable system. The EMT-3 is also ideal for use as an • Standard Aircraft filler for easy filling emergency oxygen system. The system lasts 25 minutes at • Convenient top mounted ON/OFF valve 2.5 LPM @ 25,000 FT. -

8900.1 Vol. 3, Ch 23, Sec 4 (SAS)

2/13/19 8900.1 CHG 647 VOLUME 3 GENERAL TECHNICAL ADMINISTRATION CHAPTER 23 FLIGHT ATTENDANT TRAINING AND QUALIFICATION PROGRAMS Section 4 Safety Assurance System: Flight Attendant General Emergency Training Curriculum Segment Source Basis: • Section 121.400, Applicability and Terms Used. • Section 121.401, Training Program: General. • Section 121.402, Training Program: Special Rules. • Section 121.403, Training Program: Curriculum. • Section 121.405, Training Program and Revision: Initial and Final Approval. • Section 121.408, Training Equipment Other Than Flight Simulation Training Devices. • Section 121.415, Crewmember and Dispatcher Training Program Requirements. • Section 121.417, Crewmember Emergency Training. • Section 121.418, Differences Training and Related Aircraft Differences Training. • Section 121.421, Flight Attendants: Initial and Transition Ground Training. • Section 121.427, Recurrent Training. • Section 121.434, Operating Experience, Operating Cycles, and Consolidation of Knowledge and Skills. • Section 121.801, Applicability. • Section 121.805, Crewmember Training for In-Flight Medical Events. • Appendix A to Part 121, First Aid Kits and Emergency Medical Kits. • Section 135.291, Applicability. • Section 135.295, Initial and Recurrent Flight Attendant Crewmember Testing Requirements. • Section 135.321, Applicability and Terms Used. • Section 135.323, Training Program: General. • Section 135.324, Training Program: Special Rules • Section 135.325, Training Program and Revision: Initial and Final Approval. • Section 135.327, Training Program: Curriculum. • Section 135.329, Crewmember Training Requirements. • Section 135.331, Crewmember Emergency Training. • Section 135.349, Flight Attendants: Initial and Transition Ground Training. • Section 135.351, Recurrent Training. 3-1791 GENERAL. This section provides direction and guidance on the content, evaluation, and approval of the flight attendant (F/A) general emergency training curriculum segments. -

N+3 Aircraft Concept Designs and Trade Studies

Volume 1: N+3 Aircraft Concept Designs and Trade Studies FINAL REPORT Cooperative Agreement Number NNX08AW63A Submitted to: Hyun Dae Kim Project Technical Monitor NASA Glenn Research Center Mail Stop 5-11 21000 Brookpark Road Cleveland, OH 44135 Prepared by: The MIT, Aurora Flight Sciences, and Pratt&Whitney Team E. M. Greitzer, Principal Investigator H. N. Slater Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics Massachusetts Institute of Technology 31 March 2010 1 Program Abstract MIT, Aerodyne Research, Aurora Flight Sciences, and Pratt & Whitney have collaborated to address NASA’s desire to pursue revolutionary conceptual designs for a subsonic commercial transport that could enter service in the 2035 timeframe. The MIT team brings together multidisciplinary expertise and cutting-edge technologies to determine, in a rigorous and objective manner, the potential for improvements in noise, emissions and performance for subsonic fixed wing transport aircraft. The collaboration incorporates assessment of the trade space in aerodynamics, propulsion, operations, and structures to ensure that the full spectrum of improvements is identified. Although the analysis focuses on these key areas, the team has taken a system-level approach to find the integrated solutions that offer the best balance in performance enhancements. Based on the trade space analyses and system-level assessment, two aircraft have been identified and carried through conceptual design to show both the in- depth engineering that underpins the benefits envisioned and also the technology paths that need to be followed to enable, within the next 25 years, the development of aircraft three generations ahead in capabilities from those flying today. 2 Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... -

In-Flight Breakup During Test Flight Scaled Composites Spaceshiptwom N339SS, Near Koehn Dry Lake, California October 31, 2014

In-Flight Breakup During Test Flight Scaled Composites SpaceShipTwo, N339SS Near Koehn Dry Lake, California October 31, 2014 Aerospace Accident Report NTSB/AAR-15/02 National PB2015-105454 Transportation Safety Board NTSB/AAR-15/02 PB2015-105454 Notation 8614 Adopted July 28, 2015 Aerospace Accident Report In-Flight Breakup During Test Flight Scaled Composites SpaceShipTwo, N339SS Near Koehn Dry Lake, California October 31, 2014 National Transportation Safety Board 490 L’Enfant Plaza, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20594 National Transportation Safety Board. 2015. In-Flight Breakup During Test Flight, Scaled Composites SpaceShipTwo, N339SS, Near Koehn Dry Lake, California, October 31, 2014. NTSB/AAR-15/02. Washington, DC. Abstract: This report discusses the October 31, 2014, crash involving the SpaceShipTwo (SS2) reusable suborbital rocket, N339SS, which was operated by Scaled Composites LLC. SS2 broke up into multiple pieces during a rocket-powered test flight and impacted terrain over a 5-mile area near Koehn Dry Lake, California. The pilot received serious injuries, and the copilot received fatal injuries. SS2 was destroyed, and no one on the ground was injured as a result of the falling debris. SS2 had been released from its launch vehicle, WhiteKnightTwo, N348MS, about 13 seconds before the structural breakup. Scaled was operating SS2 under an experimental permit issued by the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) Office of Commercial Space Transportation (AST) according to the provisions of 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 437. Safety -

US Navy Course Aviation Structural Mechanic E NAVEDTRA 14327

NONRESIDENT TRAINING COURSE Aviation Structural Mechanic E NAVEDTRA 14327 IMPORTANT Any future change to this course can be found at https://www.advancement.cnet.navy.mil, under Products. You should routinely check this web site. DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. PREFACE About this course: This is a self-study course. By studying this course, you can improve your professional/military knowledge, as well as prepare for the Navywide advancement-in-rate examination. It contains subject matter about day- to-day occupational knowledge and skill requirements and includes text, tables, and illustrations to help you understand the information. An additional important feature of this course is its reference to useful information in other publications. The well-prepared Sailor will take the time to look up the additional information. Any errata for this course can be found at https://www.advancement.cnet.navy.mil under Products. History of the course: ● Aug 2002: Original edition released. Authored by AMCS(AW) Rodel Henry and AMEC(AW) Ronnie Patton. ● Jan 2004: Administrative update released. Entered errata. No significant content changes were made. Published by NAVAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND TECHNOLOGY CENTER https://www.cnet.navy.mil/netpdtc POINTS OF CONTACT ADDRESS ● E-mail: [email protected] COMMANDING OFFICER ● Phone: NETPDTC N331 Toll free: (877) 264-8583 6490 SAUFLEY FIELD ROAD Comm: (850) 452-1511/1181/1859 PENSACOLA, FL 32509-5000 DSN: 922-1511/1181/1859 FAX: (850) 452-1370 Technical content assistance. Contact a Subject Matter Expert at https://www.advancement.cnet.navy.mil/welcome.asp, under Exam Info, contact your Exam Writer. -

Columbia Crew Survival Investigation Report

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Columbia Crew Survival Investigation Report NASA/SP-2008-565 Columbia Crew Survival Investigation Report NASA/SP-2008-565 Contents Contents Executive Summary................................................................................................. xix Background..................................................................................................... xix Results............................................................................................................. xix Improving Crew Survival Investigations ........................................................ xxi Introduction............................................................................................................... xxii The Columbia Accident Investigation Board Report...................................... xxii Summary of Conclusions and Recommendations........................................... xxiii Lethal events..................................................................................... xxiii Crew survival accident investigation................................................ xxvi Other................................................................................................. xxvii Summary......................................................................................................... xxvii Report Format................................................................................................. xxviii Conclusions and Recommendations ................................................................... -

8900.1 Vol. 3, Ch 19, Sec 4

4/21/20 8900.1 CHG 647 VOLUME 3 GENERAL TECHNICAL ADMINISTRATION CHAPTER 19 FLIGHTCREW MEMBER TRAINING AND QUALIFICATION PROGRAMS Section 4 Safety Assurance System: Emergency Training Curriculum Segments Source Basis: • Section 121.400, Applicability and Terms Used. • Section 121.401, Training Program: General. • Section 121.402, Training Program: Special Rules. • Section 121.403, Training Program: Curriculum. • Section 121.405, Training Program and Revision: Initial and Final Approval. • Section 121.408, Training Equipment Other Than Flight Simulation Training Devices. • Section 121.415, Crewmember and Dispatcher Training Program Requirements. • Section 121.417, Crewmember Emergency Training. • Section 121.418, Differences Training and Related Aircraft Differences Training. • Section 121.427, Recurrent Training. • Section 121.801, Applicability. • Section 121.805, Crewmember Training for In-Flight Medical Events. • Part 121 Appendix A, First Aid Kits and Emergency Medical Kits. • Section 135.321, Applicability and Terms Used. • Section 135.323, Training Program: General. • Section 135.324, Training Program: Special Rules. • Section 135.325, Training Program and Revision: Initial and Final Approval. • Section 135.327, Training Program: Curriculum. • Section 135.329, Crewmember Training Requirements. • Section 135.331, Crewmember Emergency Training. • Section 135.351, Recurrent Training. 3-1166 GENERAL. There are two types of emergency training that Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) certificate holders conducting parts -

In-Flight Entertainment Ebook, Epub

IN-FLIGHT ENTERTAINMENT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Helen Simpson | 144 pages | 06 Jun 2011 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099546122 | English | London, United Kingdom In-Flight Entertainment PDF Book The Terror: Infamy: Season 2 ; 43 mins ;. The majority of these airlines use the service provided by Gogo Wi-Fi service. Accessibility information Skip to the main content. Some airlines also present news and current affairs programming, which are often pre-recorded and delivered in the early morning before flights commence. Personal on-demand videos are stored in an aircraft's main in-flight entertainment system, whence they can be viewed on demand by a passenger over the aircraft's built in media server and wireless broadcast system. Many more learning applications continue to appear in the IFE market. Tedium: The Dull Side of the Internet. Some game systems are networked to allow interactive playing by multiple passengers. Curb Your Enthusiasm: Season 10 ; 45 mins ;. In , some airlines removed seatback screens, saving money by streaming video to passenger personal mobile devices. Flight attendants could now change movies in-flight and add short subject programming. Retrieved 24 July Some airlines upgraded the old film IFE systems to the CRT-based systems in the late s and early s on some of their older widebodies. More modern aircraft are now allowing Personal Electronic Devices PEDs to be used to connect to the on board in-flight entertainment systems. The GSM network connects to the ground infrastructure via an Inmarsat SwiftBroadband satellite which provides consistent global coverage. There are two major sections of the FAA's airworthiness regulations that regulate flight entertainment systems and their safety in transport category aircraft: 14 CFR The best examples of this changing trend are the popular trivia game series and the Berlitz Word Traveler that allows passengers to learn a new language in their own language. -

Aircraft Cabin Water Spray FAA Technical Center Atlantic City International Airport ·.·

DOT/FAA/CT-92/6 Aircraft Cabin Water Spray FAA Technical Center Atlantic City International Airport ·.·. ··:::.·dy N.J. 08405 .. ·: ... ·. C, October 1 993 Final Report .. ···········~·····.-·-document is available to the { +W#.<Nt·~•n. the National Technic . 0 U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration ilfll00013267 NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers' names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Cotolog No. DOT/FAA/CT-92/6 4. Title ond Subtitle S. Report Dote October 1993 AIRCRAFT CABIN WATER SPRAY DISBENEFITS STUDY 6. Performing Orgonizolion Code 1-,=--~~~-:------------------------------i 8. Performing Organization Report No. 7. Authorls) Thomas L. Reynolds and Kent W. Porter 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Boeing Commercial Airplane Group Payload Systems 11. Contract or Grant No. P.O. Box 3707 NASI-18027, Task 22 ... Seattle, Washington 98124-2207 13. Type of Report and Period Covered 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Final Report National Aeronautics and Federal Aviation Administration Space Administration Technical Center. Langley Research Center M/S 126 Atlantic City International Airport 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Hampton, Virginia 23665-5225 Atlantic City, New Jersey 08405 ACD-240 15. SuDDiementary Notes The FAA Contracting Officer's Technical Representative (COTR) is Mr. Richard Hill, Telephone (609) 485-5997. -

Dressing for Altitude U.S

Anybody who has watched many movies or Dennis R. Jenkins television shows has seen them—the ubiquitous About the Author silver suits worn by pilots as they explore the unknown. They are called pressure suits, and Dressing one can trace their lineage to Wiley Post or, Dressing perhaps, a bit earlier. There are two kinds of pressure suits: partial U.S. Aviation Pressure Suits–Wiley Post to Space Shuttle Pressure Suits–Wiley Post Aviation U.S. for Altitude pressure and full pressure. David Clark, once pointed out that these were not very good U.S. Aviation Pressure Suits–Wiley Post to Space Shuttle names, but they are the ones that stuck. In a partial-pressure suit, the counter-pressure is not as complete as in a full-pressure suit, but it Dennis R. Jenkins is placed so that shifts in body fl uids are kept One of the unsigned authors of an Air Force history of within reasonable limits. On the other hand, a the Wright Air Development Center wrote an epilogue full-pressure suit, which is an anthropomorphic that conveyed the awe associated with aviation pressure pressure vessel, creates an artifi cial environment suits during the mid-1950s. “The high point in the for the pilot. development of the altitude suit was reached on June for 17, 1954 when Maj. Arthur Murray rode the rocket- One type of pressure suit is not necessarily propelled X-1A to an altitude in excess of 90,000 feet. “better” than the other, and both partial-pressure When Murray reached the peak of his record setting and full-pressure suits are still in limited use fl ight, he was atop more than 97 percent of the atmo- around the world.