Provincial Archaeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Langelier Index Summary for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland

Water Resources Langelier Index Summary for Public Water Supplies in Management Division Newfoundland and Labrador Community Name Serviced Area Source Name Sample Date Langelier Index Bauline Bauline #1 Brook Path Well May 29, 2020 -1.06 Bay St. George South Highlands #3 Brian Pumphrey Well May 20, 2020 -0.29 Highlands Birchy Bay Birchy Bay Jumper's Pond May 06, 2020 -2.64 Bonavista Bonavista Long Pond May 01, 2020 -1.77 Brent's Cove Brent's Cove Paddy's Pond May 19, 2020 -5.85 Centreville-Wareham-Trinity Trinity Southwest Feeder Pond May 21, 2020 -3.64 Chance Cove Upper Cove Hollett's Well Jun 11, 2020 -2.17 Channel-Port aux Basques Channel-Port Aux Basques Gull Pond & Wilcox Pond May 20, 2020 -2.41 Clarenville Clarenville, Shoal Harbour Shoal Harbour River Jun 05, 2020 -2.23 Conception Bay South Conception Bay South Bay Bulls Big Pond May 28, 2020 -1.87 Corner Brook Corner Brook (+Massey Trout Pond, Third Pond (2 Jun 19, 2020 -1.88 Drive, +Mount Moriah) intakes) Fleur de Lys Fleur De Lys First Pond, Narrow Pond May 19, 2020 -3.41 Fogo Island Fogo Freeman's Pond Jun 09, 2020 -6.65 Fogo Island Fogo Freeman's Pond Jun 09, 2020 -6.54 Fogo Island Fogo Freeman's Pond Jun 09, 2020 -6.33 Gander Gander Gander Lake May 25, 2020 -2.93 Gander Bay South Gander Bay South - PWDU Barry's Brook May 20, 2020 -4.98 Gander Bay South George's Point, Harris Point Barry's Brook May 20, 2020 -3.25 Grand Falls-Windsor Grand Falls-Windsor Northern Arm Lake Jun 01, 2020 -2.80 (+Bishop's Falls, +Wooddale, +Botwood, +Peterview) Grates Cove Grates Cove Centre #1C -

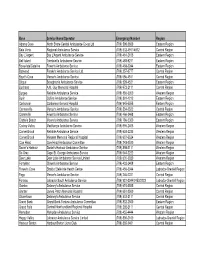

Revised Emergency Contact #S for Road Ambulance Operators

Base Service Name/Operator Emergency Number Region Adams Cove North Shore Central Ambulance Co-op Ltd (709) 598-2600 Eastern Region Baie Verte Regional Ambulance Service (709) 532-4911/4912 Central Region Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Ambulance Service (709) 461-2105 Eastern Region Bell Island Tremblett's Ambulance Service (709) 488-9211 Eastern Region Bonavista/Catalina Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 468-2244 Eastern Region Botwood Freake's Ambulance Service Ltd. (709) 257-3777 Central Region Boyd's Cove Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 656-4511 Central Region Brigus Broughton's Ambulance Service (709) 528-4521 Eastern Region Buchans A.M. Guy Memorial Hospital (709) 672-2111 Central Region Burgeo Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 886-3350 Western Region Burin Collins Ambulance Service (709) 891-1212 Eastern Region Carbonear Carbonear General Hospital (709) 945-5555 Eastern Region Carmanville Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 534-2522 Central Region Clarenville Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 466-3468 Eastern Region Clarke's Beach Moore's Ambulance Service (709) 786-5300 Eastern Region Codroy Valley MacKenzie Ambulance Service (709) 695-2405 Western Region Corner Brook Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 634-2235 Western Region Corner Brook Western Memorial Regional Hospital (709) 637-5524 Western Region Cow Head Cow Head Ambulance Committee (709) 243-2520 Western Region Daniel's Harbour Daniel's Harbour Ambulance Service (709) 898-2111 Western Region De Grau Cape St. George Ambulance Service (709) 644-2222 Western Region Deer Lake Deer Lake Ambulance -

The Newfoundland and Labrador Gazette

No Subordinate Legislation received at time of printing THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE PART I PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Vol. 84 ST. JOHN’S, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2009 No. 43 EMBALMERS AND FUNERAL DIRECTORS ACT, 2008 NOTICE The following is a list of names and addresses of Funeral Homes 2009 to whom licences and permits have been issued under the Embalmers and Funeral Directors Act, cE-7.1, SNL2008 as amended. Name Street 1 City Province Postal Code Barrett's Funeral Home Mt. Pearl 328 Hamilton Avenue St. John's NL A1E 1J9 Barrett's Funeral Home St. John's 328 Hamilton Avenue St. John's NL A1E 1J9 Blundon's Funeral Home-Clarenville 8 Harbour Drive Clarenville NL A5A 4H6 Botwood Funeral Home 147 Commonwealth Drive Botwood NL A0H 1E0 Broughton's Funeral Home P. O. Box 14 Brigus NL A0A 1K0 Burin Funeral Home 2 Wilson Avenue Clarenville NL A5A 2B6 Carnell's Funeral Home Ltd. P. O. Box 8567 St. John's NL A1B 3P2 Caul's Funeral Home St. John's P. O. Box 2117 St. John's NL A1C 5R6 Caul's Funeral Home Torbay P. O. Box 2117 St. John's NL A1C 5R6 Central Funeral Home--B. Falls 45 Union Street Gr. Falls--Windsor NL A2A 2C9 Central Funeral Home--GF/Windsor 45 Union Street Gr. Falls--Windsor NL A2A 2C9 Central Funeral Home--Springdale 45 Union Street Gr. Falls--Windsor NL A2A 2C9 Conway's Funeral Home P. O. Box 309 Holyrood NL A0A 2R0 Coomb's Funeral Home P. O. Box 267 Placentia NL A0B 2Y0 Country Haven Funeral Home 167 Country Road Corner Brook NL A2H 4M5 Don Gibbons Ltd. -

Thms Summary for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland And

THMs Summary for Public Water Supplies Water Resources Management Division in Newfoundland and Labrador Community Name Serviced Area Source Name THMs Average Average Total Samples Last Sample (μg/L) Type Collected Date Anchor Point Anchor Point Well Cove Brook 154.13 Running 72 Feb 25, 2020 Appleton Appleton (+Glenwood) Gander Lake (The 68.30 Running 74 Feb 03, 2020 Outflow) Aquaforte Aquaforte Davies Pond 326.50 Running 52 Feb 05, 2020 Arnold's Cove Arnold's Cove Steve's Pond (2 142.25 Running 106 Feb 27, 2020 Intakes) Avondale Avondale Lee's Pond 197.00 Running 51 Feb 18, 2020 Badger Badger Well Field, 2 wells on 5.20 Simple 21 Sep 27, 2018 standby Baie Verte Baie Verte Southern Arm Pond 108.53 Running 25 Feb 12, 2020 Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Pond 0.00 Simple 9 Dec 13, 2018 Barachois Brook Barachois Brook Drilled 0.00 Simple 8 Jun 21, 2019 Bartletts Harbour Bartletts Harbour Long Pond (same as 0.35 Simple 2 Jan 18, 2012 Castors River North) Bauline Bauline #1 Brook Path Well 94.80 Running 48 Mar 10, 2020 Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Sugarloaf Hill Pond 117.83 Running 68 Mar 03, 2020 Bay Roberts Bay Roberts, Rocky Pond 38.68 Running 83 Feb 11, 2020 Spaniard's Bay Bay St. George South Heatherton #1 Well Heatherton 8.35 Simple 7 Dec 03, 2013 (Home Hardware) Bay St. George South Jeffrey's #1 Well Jeffery's (Joe 0.00 Simple 5 Dec 03, 2013 Curnew) Bay St. George South Robinson's #1 Well Robinson's 3.30 Simple 4 Dec 03, 2013 (Louie MacDonald) Bay St. -

Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

A GRAVITY SU VEY A ERN NOTR BAY, N W UNDLAND CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author's Permission) HUGH G. Ml rt B. Sc. (HOI S.) ~- ··- 223870 A GRAVITY SURVEY OF EASTERN NOTRE DAME BAY, NEWFOUNDLAND by @ HUGH G. MILLER, B.Sc. {HCNS.) .. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, Memorial University of Newfoundland. July 20, 1970 11 ABSTRACT A gravity survey was undertaken on the archipelago and adjacent coast of eastern Notre Dame Bay, Newfoundland. A total of 308 gravity stations were occupied with a mean station spacing of 2,5 km, and 9 gravity sub-bases were established. Elevations for the survey were determined by barometric and direct altimetry. The densities of rock samples collected from 223 sites were detenmined. A Bouguer anomaly map was obtained and a polynomial fitting technique was employed to determine the regional contribution to the total Bouguer anomaly field. Residual and regional maps based on a fifth order polynomial were obtained. Several programs were written for the IBM 360/40 computer used in this and model work. Three-dimensional model studies were carried out and a satisfactory overall fit to the total Bouguer field was obtained. Several shallow features of the anomaly maps were found to correlate well with surface bodies, i.e. granite or diorite bodies. Sedimentary rocks had little effect on the gravity field. The trace of the Luke's Arm fault was delineated. The following new features we r~ discovered: (1) A major structural discontinuity near Change Islands; (2) A layer of relatively high ·density (probably basic to ultrabasic rock) at 5 - 10 km depth. -

Bird Cove, Anchor Point, Flower's Cover ICSP

Integrated Community Sustainability Plan Submitted to: Department of Municipal Affairs Government of Newfoundland and Labrador PO Box 8700 St. John’s, NL A1B 4J6 Developed by: Town of Bird Cove Town of Anchor Point Town of Flower’s Cove 67 Michael’s Drive PO Box 117 PO Box 149 Bird Cove, NL Anchor Point, NL Flower’s Cove, NL A0K 1L0 A0K 1A0 A0K 2N0 Ph # 709-247-2256 Ph # 709-456-2011 Ph # 709-456-2124 Integrated Community Sustainability Plan Town of Bird Cove, Anchor Point & Flower’s Cove Table of Contents 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................................ 2 2. Collaboration / Partnership ........................................................................................................................ 5 3. Regional Assessments................................................................................................................................ 9 4. Vision - Working Toward Sustainable Communities.............................................................................. 18 5. Community Strategic Goals and Actions................................................................................................ 21 6. Pillars ...................................................................................................................................................... 22 7. Implementation, Monitoring and Evaluation.......................................................................................... 61 8. -

January 2007

Volume XXV111 Number 1 January 2007 IN THIS ISSUE... VON Nurses Helping the Public Stay on Their Feet Province Introduces New Telecare Service New School Food Guidelines Sweeping the Nation Tattoos for You? Trust Awards $55,000 ARNNL www.arnnl.nf.ca Staff Executive Director Jeanette Andrews 753-6173 [email protected] Director of Regulatory Heather Hawkins 753-6181 Services [email protected] Nursing Consultant - Pegi Earle 753-6198 Health Policy & [email protected] - Council Communications Pat Pilgrim, President 2006-2008 Nursing Consultant - Colleen Kelly 753-0124 Jim Feltham, President-Elect 2006-2008 Education [email protected] Ann Shears, Public Representative 2004-2006 Nursing Consultant - Betty Lundrigan 753-6174 Ray Frew, Public Representative 2004-2006 Advanced Practice & [email protected] Kathy Watkins, St. John's Region 2006-2009 Administration Kathy Elson, Labrador Region 2005-2008 Nursing Consultant - Lynn Power 753-6193 Janice Young, Western Region 2006-2009 Practice [email protected] Bev White, Central Region 2005-2008 Project Consultant JoAnna Bennett 753-6019 Ann Marie Slaney, Eastern Region 2004-2007 QPPE (part-time) [email protected] Cindy Parrill, Northern Region 2004-2007 Accountant & Office Elizabeth Dewling 753-6197 Peggy O'Brien-Connors, Advanced Practice 2006-2009 Manager [email protected] Kathy Fitzgerald, Practice 2006-2009 Margo Cashin, Practice 2006-2007 Secretary to Executive Christine Fitzgerald 753-6183 Director and Council [email protected] Catherine Stratton, Nursing Education/Research -

Bibliothèque Et Archives Canada

Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-88023-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-88023-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. without the author's permission. In compliance with the Canadian Conformement a la loi canadienne sur la Privacy Act some supporting forms protection de la vie privee, quelques may have been removed from this formulaires secondaires ont ete enleves de thesis. -

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador ii Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Publication Series, Newfoundland and Labrador Region No. 0008 March 2009 Revised April 2010 Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador Prepared by 1 Intervale Associates Inc. Prepared for Oceans Division, Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Branch Fisheries and Oceans Canada Newfoundland and Labrador Region2 Published by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador Region P.O. Box 5667 St. John’s, NL A1C 5X1 1 P.O. Box 172, Doyles, NL, A0N 1J0 2 1 Regent Square, Corner Brook, NL, A2H 7K6 i ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011 Cat. No. Fs22-6/8-2011E-PDF ISSN1919-2193 ISBN 978-1-100-18435-7 DFO/2011-1740 Correct citation for this publication: Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2011. Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador. OHSAR Pub. Ser. Rep. NL Region, No.0008: xx + 173p. ii iii Acknowledgements Many people assisted with the development of this report by providing information, unpublished data, working documents, and publications covering the range of subjects addressed in this report. We thank the staff members of federal and provincial government departments, municipalities, Regional Economic Development Corporations, Rural Secretariat, nongovernmental organizations, band offices, professional associations, steering committees, businesses, and volunteer groups who helped in this way. We thank Conrad Mullins, Coordinator for Oceans and Coastal Management at Fisheries and Oceans Canada in Corner Brook, who coordinated this project, developed the format, reviewed all sections, and ensured content relevancy for meeting GOSLIM objectives. -

The Hitch-Hiker Is Intended to Provide Information Which Beginning Adult Readers Can Read and Understand

CONTENTS: Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: The Southwestern Corner Chapter 2: The Great Northern Peninsula Chapter 3: Labrador Chapter 4: Deer Lake to Bishop's Falls Chapter 5: Botwood to Twillingate Chapter 6: Glenwood to Gambo Chapter 7: Glovertown to Bonavista Chapter 8: The South Coast Chapter 9: Goobies to Cape St. Mary's to Whitbourne Chapter 10: Trinity-Conception Chapter 11: St. John's and the Eastern Avalon FOREWORD This book was written to give students a closer look at Newfoundland and Labrador. Learning about our own part of the earth can help us get a better understanding of the world at large. Much of the information now available about our province is aimed at young readers and people with at least a high school education. The Hitch-Hiker is intended to provide information which beginning adult readers can read and understand. This work has a special feature we hope readers will appreciate and enjoy. Many of the places written about in this book are seen through the eyes of an adult learner and other fictional characters. These characters were created to help add a touch of reality to the printed page. We hope the characters and the things they learn and talk about also give the reader a better understanding of our province. Above all, we hope this book challenges your curiosity and encourages you to search for more information about our land. Don McDonald Director of Programs and Services Newfoundland and Labrador Literacy Development Council ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the many people who so kindly and eagerly helped me during the production of this book. -

ROUTING GUIDE - Less Than Truckload

ROUTING GUIDE - Less Than Truckload Updated December 17, 2019 Serviced Out Of City Prov Routing City Carrier Name ABRAHAMS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADAMS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADEYTON NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADMIRALS BEACH NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADMIRALS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ALLANS ISLAND NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point AMHERST COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ANCHOR POINT NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ANGELS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point APPLETON NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point AQUAFORTE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ARGENTIA NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ARNOLDS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ASPEN COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ASPEY BROOK NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point AVONDALE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BACK COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BACK HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BACON COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BADGER NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BADGERS QUAY NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAIE VERTE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAINE HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAKERS BROOK NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARACHOIS BROOK NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARENEED NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARR'D HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARR'D ISLANDS NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARTLETTS HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAULINE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAULINE EAST NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAY BULLS NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAY DE VERDE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAY L'ARGENT NL TORONTO, ON -

A Brief History of the Random Region of Trinity Bay

A Brief History of the Random Region of Trinity Bay A Presentation to the Wessex Society St. John's, Nfld. Leslie J. Dean April, 1994 Revised June 16, 1997 HISTORY OF THE RANDOM REGION OF TRINITY BAY INTRODUCTION The region encompassed by the Northwest side of Trinity Bay bounded by Southwest Arm (of Random), Northwest Arm (of Random), Smith's Sound and Random Island has, over the years, been generally referred to as "Random". However, "Random" is now generally interpreted locally as that portion of the region encompassing Southwest Arm and Northwest Arm. Effective settlement of the region as a whole occurred largely during the 1857 - 1884 period. A number of settlements at the outer fringes of the region including Rider's Harbour at the eastern extremity of Random Island and "Harts Easse" at the entrance to Random Sound were settled much earlier. Indeed, these two settlements together with Ireland's Eye near the eastern end of Random Island, were locations of British migratory fishing activity in Trinity Bay throughout the l600s and 1700s. "Harts Easse" was the old English name for Heart's Ease Beach. One of the earliest references to the name "Random" is found on the 1689 Thornton's map of Newfoundland which shows Southwest Arm as River Random. It is possible that the region's name can be traced to the "random" course which early vessels took when entering the region from the outer reaches of Trinity Bay. In all likelihood, however, the name is derived from the word random, one meaning of which is "choppy" or "turbulence", which appropriately describes 2 sea state conditions usually encountered at the region's outer headlands of West Random Head and East Random Head.