'A Large House on the Downs': Household Archaeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newfoundland Antique and Classic Car Club (NACCC) April – June 2008

Newfoundland Antique and Classic Car Club (NACCC) April – June 2008 Iron Wood Shopping Mall, Richmond BC (Picture compliments of Walter and Shirley LaCour) President’s Message Another cruising season has started and Classic Wheels 2008 Car show is now history. Time surely flies when we are having fun getting prepared for the show. I would like to thank all the members who participated in the show whether it was helping to plan the car show, showing your car, volunteering with ticket sales or whatever. Without your help it would be impossible to do such an event. Congratulations to all the trophy winners. It is very difficult to choose from such beautiful classic automobiles. According to the list of activities and events in the calendar it seems we will have a very busy season. We suggest you refer to the calendar for events that will interest you. Of special note is a show and shine on July 1 at the Royal Canadian Legion Branch 1 for our veterans. A large attendance will show our thanks to all the veterans from past and present for the sacrifice they made for us. There will be information in the newsletter pertaining to this. Our car club plans to visit the A&W on Cunard Crescent, in Donavans on a regular basis every second Thursday night. Owner, Scott Bartlett, promises to make our visits interesting and will give the club a percentage for A&W catalogue merchandise purchased. Please remember cruising and socializing is what our club is all about so get out and meet up with the members and enjoy our short cruising season. -

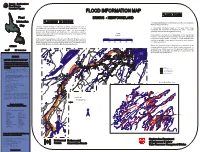

FLOOD INFORMATION MAP FLOOD ZONES Flood BRIGUS - NEWFOUNDLAND

Canada - Newfoundland Flood Damage Reduction Program FLOOD INFORMATION MAP FLOOD ZONES Flood BRIGUS - NEWFOUNDLAND Information FLOODING IN BRIGUS A "designated floodway" (1:20 flood zone) is the area subject to the most frequent flooding. Map Flooding causes damage to personal property, disrupts the lives of individuals and communities, and can be a threat to life itself. Continuing Beth A "designated floodway fringe" (1:100 year flood zone) development of flood plain increases these risks. The governments of une' constitutes the remainder of the flood risk area. This area Canada and Newfoundland and Labrador are sometimes asked to s Po generally receives less damage from flooding. compensate property owners for damage by floods or are expected to find Scale nd solutions to these problems. (metres) No building or structure should be erected in the "designated floodway" since extensive damage may result from deeper and While most of the past flood events on Lamb's Brook in Brigus have been more swiftly flowing waters. However, it is often desirable, and caused by a combination of high flows and ice jams at hydraulic structures may be acceptable, to use land in this area for agricultural or floods can occur due to heavy rainfall and snow melt. This was the case in 0 200 400 600 800 1000 recreational purposes. January 1995 when the Conception Bay Highway was flooded. Within the "floodway fringe" a building, or an alteration to an BRIGUS existing building, should receive flood proofing measures. A variety of these may be used, e.g.. the placing of a dyke around Canada Newfoundland the building, the construction of a building on raised land, or by Brigus the special design of a building. -

Thms Summary for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland And

THMs Summary for Public Water Supplies Water Resources Management Division in Newfoundland and Labrador Community Name Serviced Area Source Name THMs Average Average Total Samples Last Sample (μg/L) Type Collected Date Anchor Point Anchor Point Well Cove Brook 154.13 Running 72 Feb 25, 2020 Appleton Appleton (+Glenwood) Gander Lake (The 68.30 Running 74 Feb 03, 2020 Outflow) Aquaforte Aquaforte Davies Pond 326.50 Running 52 Feb 05, 2020 Arnold's Cove Arnold's Cove Steve's Pond (2 142.25 Running 106 Feb 27, 2020 Intakes) Avondale Avondale Lee's Pond 197.00 Running 51 Feb 18, 2020 Badger Badger Well Field, 2 wells on 5.20 Simple 21 Sep 27, 2018 standby Baie Verte Baie Verte Southern Arm Pond 108.53 Running 25 Feb 12, 2020 Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Pond 0.00 Simple 9 Dec 13, 2018 Barachois Brook Barachois Brook Drilled 0.00 Simple 8 Jun 21, 2019 Bartletts Harbour Bartletts Harbour Long Pond (same as 0.35 Simple 2 Jan 18, 2012 Castors River North) Bauline Bauline #1 Brook Path Well 94.80 Running 48 Mar 10, 2020 Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Sugarloaf Hill Pond 117.83 Running 68 Mar 03, 2020 Bay Roberts Bay Roberts, Rocky Pond 38.68 Running 83 Feb 11, 2020 Spaniard's Bay Bay St. George South Heatherton #1 Well Heatherton 8.35 Simple 7 Dec 03, 2013 (Home Hardware) Bay St. George South Jeffrey's #1 Well Jeffery's (Joe 0.00 Simple 5 Dec 03, 2013 Curnew) Bay St. George South Robinson's #1 Well Robinson's 3.30 Simple 4 Dec 03, 2013 (Louie MacDonald) Bay St. -

TACOG Dialogue Transcript

1 TAKING A CHANCE ON GOD Transcription for Subtitles Mike Wallace (The Homosexuals): 00:04 Most Americans are repelled by the mere notion of homosexuality. The CBS News survey shows that two out of three Americans look upon homosexuals with disgust, discomfort or fear. Anita Bryant: 00:16 If homosexuals are allowed their civil rights, then so will prostitutes or thieves or anyone else. Jimmy Swaggart: 00:21 I've never seen a man in my life that I wanted to marry. And I'm gonna be blunt and plain. If one ever looks at me like that I'm gonna kill him and tell God he died. In case anybody doesn't know, God calls it an abomination. It's an abom-NATION! It's an abom-NATION! Titles: 00:55 Silence To Speech Productions Presents A Film by Brendan Fay Taking a Chance on God Phil Donahue 01:19 You are now about to be bounced from the Jesuits. They’re the smartest, you study the longest, you’re the most powerful and now you’re being bounced. Larry King 01:30 How early on in life did you discover your own homosexuality? Bishop Gene Robinson: 01:36 There is nothing so powerful as one person living a life of integrity. That's exactly what John McNeill has done. That's what Harvey Milk did. I mean, name all of the great heroes of our movement and that is what is changing the world. 2 Andy Humm: 1:54 And it's not just among the Catholic church. -

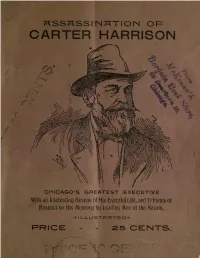

Assassination of Carter Harrison

HSSMSS1NHTION OR CARTER HARRISON CHICAGO'S GREATEST EXECUTIVE With an Intetesting Review of His Eventful Life, and Tributes of Respect to His Memory by Leading Men of the Nation. - I L- LUST R T^TO D K- PRICE: - - 25 CENTS. CdRTER HflRRISON'J flSSflSSIN/ITION Giving a full account of his Tragic Death, with a Detailed Synopsis of his Eventful Life. COMPILED BY A MEMBER OF THE CHICAGO PRESS. WITH AUTHOR'S INTRODUCTORY. FROM THE PRESS OF A. THEO. PATTERSON, PROGRESSIVE PRINTER INTRODUCTORY. (BARTER HENRY HARRISON is no more, save in memory. A cruel assassin took his life at a time when fair Fame upon him smiled her sweetest. As Mayor of the World's Fair City, together with his brilliant talents and past political achievements, ]ie had won the admiration of the World. This little book is not a biography such as should do full justice to the memory of the late Mayor Harrison. Such a work will no doubt be published, but its inevitable high price will place it beyond the reach of the masses of the people. This brief compilation, which I have put into book form, contains all the main facts connected with the tragedy, and other information worthy of preservation. If tf\\* book shall reach the masses of the people and be pre- served by them as a memento of the man who owed his great success to their loyal political support, then the author's desire shall be attained. THE AUTHOR. fttayor Jtoison Assassinated. "Carter H. Harrison, five times elected Mayor of the City of Chicago, was assassinated at his home on the night of October 28, 1893. -

ARCHIVES and SPECIAL COLLECTIONS QUEEN ELIZABETH II LIBRARY MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY, ST

ARCHIVES and SPECIAL COLLECTIONS QUEEN ELIZABETH II LIBRARY MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY, ST. JOHN'S, NL Mary Schwall Photograph Collection COLL-206 Website: Archives and Special Collections Author: Bert Riggs Date: 1996 Scope and Content: This collection consists of 135 photographs taken by Mary Schwall or her companions while on excursions to Newfoundland during 1913 and 1915. They are a pictorial record of a journey by ship from Nova Scotia to Newfoundland, a train trip from Channel to St. John's, and a trip from St. John's north around the coast to St. Anthony, across the Strait of Belle Isle to Labrador and down the west coast of the Great Northern Peninsula. There is evidence that the photographs were taken during two trips to Newfoundland, as two photographs have the date 1913 on the back with the caption, while another has the date 1915. The photographs provide visual documentation of Mary Schwall's vacations, but they also provide valuable information on Newfoundland communities during the early years of the twentieth century. Vernacular architecture historians have attested to the fact that several of the photographs show buildings only previously known through oral accounts. As well there is visual documentation of people, especially children, which can provide information on lifestyle, dress, nutrition, disease, and a host of other subjects.In addition, there are 56 postcards with images covering much the same geographical area as the photographs, leading one to believe that they were purchased in larger communities during stopovers, or possibly in St. John's. Most of the postcards were produced for the St. -

MINUTES June 13, 2018 at 6:30 P.M

Northeast Avalon Joint Council Meeting MINUTES June 13, 2018 at 6:30 p.m. St. Thomas Line Community Centre, 2 Neary Road, Paradise, NL ATTENDEES: • Joedy Wall, Pouch Cove (Chair) • Bill Antle, Mount Pearl (Vice Chair) • Sam Whalen, Colliers (Treasurer) • Deborah Quilty, Paradise • Bridget Hynes, Colliers • Corrina Martin, Flatrock • Michelle Martin, Flatrock • Madonna Stewart-Sharpe, Portugal Cove-St. Philips • Kevin Costello, Holyrood • Mike Doyle, Harbour Main-Chapel’s Cove-Lakeview • Craig Williams, Conception Harbour • Jamie Korab, St. John’s • Bradley Power, Eastern Regional Service Board & Logy Bay-Middle Cove-Outer Cove PROCEEDINGS: 1. CALL TO ORDER – The meeting was called to order by Chairperson Joedy Wall at 6:35 p.m. 2. ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA MOTION: It was moved by Mr. Antle, seconded by Ms. M. Martin, that the agenda be adopted as presented. All in favour. Motion carried. Ref#: NEAJC2018-013 3. DELEGATION(S) a) Neil Dawe, Tract Consulting: Mr. Neil Dawe and Ms. Corrina Dawe thanked the joint council for the opportunity to meet and present on municipal asset management and the work Tract Consulting Inc. is doing throughout the region. Mr. Dawe used a PowerPoint presentation which is included as an attachment to this document. Mr. Dawe took questions after the presentation concluded: 1. What is the biggest barrier to communities engaging in the development of an Asset Management Plan? Cost is not always a barrier; most plans are relatively low cost. Land ownership is an issue in most, if not all communities. 2. How much funding can a community attain from the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) for the development of a plan? FCM offers up to $60,000 to successful municipal applicants. -

(PL-557) for NPA 879 to Overlay NPA

Number: PL- 557 Date: 20 January 2021 From: Canadian Numbering Administrator (CNA) Subject: NPA 879 to Overlay NPA 709 (Newfoundland & Labrador, Canada) Related Previous Planning Letters: PL-503, PL-514, PL-521 _____________________________________________________________________ This Planning Letter supersedes all previous Planning Letters related to NPA Relief Planning for NPA 709 (Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada). In Telecom Decision CRTC 2021-13, dated 18 January 2021, Indefinite deferral of relief for area code 709 in Newfoundland and Labrador, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) approved an NPA 709 Relief Planning Committee’s report which recommended the indefinite deferral of implementation of overlay area code 879 to provide relief to area code 709 until it re-enters the relief planning window. Accordingly, the relief date of 20 May 2022, which was identified in Planning Letter 521, has been postponed indefinitely. The relief method (Distributed Overlay) and new area code 879 will be implemented when relief is required. Background Information: In Telecom Decision CRTC 2017-35, dated 2 February 2017, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) directed that relief for Newfoundland and Labrador area code 709 be provided through a Distributed Overlay using new area code 879. The new area code 879 has been assigned by the North American Numbering Plan Administrator (NANPA) and will be implemented as a Distributed Overlay over the geographic area of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador currently served by the 709 area code. The area code 709 consists of 211 Exchange Areas serving the province of Newfoundland and Labrador which includes the major communities of Corner Brook, Gander, Grand Falls, Happy Valley – Goose Bay, Labrador City – Wabush, Marystown and St. -

MINUTES Upper Island Cove Town Hall Thursday, January 26, 2017 @ 7:30 P.M

JOINT COUNCIL OF CONCEPTION BAY NORTH MINUTES Upper Island Cove Town Hall Thursday, January 26, 2017 @ 7:30 p.m. IN ATTENDANCE: MEMBER NAME TOWN/ORGANIZATION Gord Power, Chair/Treasurer Cupids Elizabeth Moore Clarke's Beach Frank Antle, Secretary Victoria George Simmons Bay Roberts Philip Wood Bay Roberts Wade Oates Bay Roberts Walter Yetman Bay Roberts Dean Franey Bay Roberts Wayne Rose Brigus Ralph Trickett Brigus Lorne Youden Brigus George Butt Carbonear Wayne Snow Clarke's Beach Joan Wilcox Clarke's Beach Christine Burry Cupids Kevin Connolly Cupids Terry Barnes Harbour Grace Gordon Stone Harbour Grace Blair Hurley North River Marjorie Dawson South River Bev Wells South River Joyce Petten South River Arthur Petten South River Lewis Sheppard Spaniard’s Bay Tony Dominix Spaniard's Bay Tracy Smith Spaniard's Bay George Adams Upper Island Cove Brian Drover Upper Island Cove Aubrey Rose Victoria Others: Ken McDonald Member of Parliament Pam Parsons Member of the House of Assembly Ken Carter Parliamentary Staff Sgt. Brent Hillier RCMP Kathleen Parewick Municipalities NL Bradley Power Eastern Regional Service Board Andrew Robinson The Compass 2 PROCEEDINGS: 1. WELCOME FROM HOST MUNICIPALITY - Mayor George Adams from the Town of Upper Island Cove welcomed everyone to his community and invited guests to stay after the meeting for a small reception. 2. WELCOME FROM THE CHAIRPERSON - Chairperson Gordon Power welcomed everyone and called the meeting to order at 7:34 p.m. 3. ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA MOTION: Moved by Mr. G Stone, seconded by Mr. W. Yetman, that the Agenda of the JCCBN meeting of January 26, 2017 be adopted as tabled. -

Summary of Polling Divisions HARBOUR MAIN

Summary of Polling Divisions HARBOUR MAIN Total Number of Polling Divisions in District: 40 Total Number of Registered Electors in District: 11004 Polling Division Boundary Descriptions Registered Electors 1. CONCEPTION BAY SOUTH: ANTHONYS ROAD (ODD NUMBERS 9 TO 59, THE WEST SIDE OF 393 ANTHONYS ROAD INCLUDING ADMIRALS' COAST RETIREMENT CENTRE, 29 ANTHONYS ROAD); CONCEPTION BAY HIGHWAY (ODD NUMBERS 943 TO 1061, SOUTH PORTION OF CONCEPTION BAY HIGHWAY FROM LOWER GULLIES RIVER TO SCOTTS ROAD SOUTH, EVEN NUMBERS 1020 TO 1090, FROM ANTHONY'S ROAD TO SCOTTS ROAD NORTH INCLUDING MORGANS COMMUNITY CARE HOME, 1028 CONCEPTION BAY HIGHWAY); DECIMA PLACE; HOLLOWAY PLACE; ISRAEL PLACE; MACMAR LANE; PICCOS ROAD; RED OAKE PLACE; ROBERTS ROAD NORTH; AND UPSHALL PLACE. 2. CONCEPTION BAY SOUTH: BEACON PLACE; BIRCHY HOLLOW; CRAIG NEWMAN WAY (ALSO 361 KNOWN AS CLOVER LANE); FOREST ROAD; GREENRIDGE PLACE; LARCH GROVE PLACE; QUIET WAY; ROBERTS ROAD SOUTH; ROCK VIEW ROAD; RONALD DRIVE; SCOTTS ROAD SOUTH; SOPER PLACE; AND UPPER GULLIES ELEMENTARY ROAD. 3. CONCEPTION BAY SOUTH: AGUSTUS AVENUE; ANDREWS ROAD; BIRCHMOUNT PLACE; 470 CHATWOOD CRESCENT; COLE THOMAS DRIVE; COLLEY ROAD; COMERFORDS ROAD; CONCEPTION BAY HIGHWAY (ODD NUMBERS 1063 TO 1231, INCLUDING WINDY HILL MANOR, 1197 CONCEPTION BAY HIGHWAY, THE SOUTHERN PORTION OF CONCEPTION BAY HIGHWAY FROM SCOTT'S ROAD TO PETTENS ROAD); COURTELL HEIGHTS; DOMINIC DRIVE; GARRETT STREET; MAUREEN CRESCENT; MAYA PLACE; SAMUEL DRIVE; SHETLAND PLACE; ST. PETERS ROAD; AND TAMARA PLACE. 4. CONCEPTION BAY SOUTH: CASEYS ROAD; COATES ROAD; CONCEPTION BAY HIGHWAY (EVEN 337 NUMBERS 1100 TO 1256); DAWES HILL ROAD; HERITAGE ROAD; JASMINE PLACE; KENNEDYS ROAD; LIONS HOUSING ROAD; LUSHS ROAD; SCOTTS LANE NORTH; SCOTTS ROAD NORTH; AND WARFORDS ROAD. -

The Seventeenth Century Brewhouse and Bakery at Ferryland, Newfoundland

Northeast Historical Archaeology Volume 41 Article 2 2012 The eveS nteenth Century Brewhouse and Bakery at Ferryland, Newfoundland Arthur R. Clausnitzer Jr. Barry C. Gaulton Follow this and additional works at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Clausnitzer, Arthur R. Jr. and Gaulton, Barry C. (2012) "The eS venteenth Century Brewhouse and Bakery at Ferryland, Newfoundland," Northeast Historical Archaeology: Vol. 41 41, Article 2. https://doi.org/10.22191/neha/vol41/iss1/2 Available at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha/vol41/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Northeast Historical Archaeology by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Northeast Historical Archaeology/Vol. 41, 2012 1 The Seventeenth-Century Brewhouse and Bakery at Ferryland, Newfoundland Arthur R. Clausnitzer, Jr. and Barry C. Gaulton In 2001 archaeologists working at the 17th-century English settlement at Ferryland, Newfoundland, uncovered evidence of an early structure beneath a mid-to-late century gentry dwelling. A preliminary analysis of the architectural features and material culture from related deposits tentatively identified the structure as a brewhouse and bakery, likely the same “brewhouse room” mentioned in a 1622 letter from the colony. Further analysis of this material in 2010 confirmed the identification and dating of this structure. Comparison of the Ferryland brewhouse to data from both documentary and archaeological sources revealed some unusual features. When analyzed within the context of the original Calvert period settlement, these features provide additional evidence for the interpretation of the initial settlement at Ferryland not as a corporate colony such as Jamestown or Cupids, but as a small country manor home for George Calvert and his family. -

Student Handbook

Students Against Drinking & Driving (S.A.D.D.) Newfoundland & Labrador Student Handbook I N D E X SECTION 1: CHAPTER EXECUTIVE INFORMATION (WHITE PAGES) 1. EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONS .............................................................................. 1 A) Election ................................................................................................... 1 B) Roles - President ..................................................................................... 2 - Vice-President ............................................................................. 3 - Vice-President of Finance ........................................................... 3 - Vice-President of Public Relations ............................................. 4 - Secretary ..................................................................................... 5 - Junior Rep .................................................................................. 6 - Teacher / Advisors ...................................................................... 7 C) Planning a Chapter Meeting .................................................................... 8 Sample Meeting Agenda .................................................................... 10 D) How to Write Minutes ............................................................................. 11 Sample Minutes Sheet ........................................................................ 12 Sample Monthly Report ..................................................................... 13 2. HOW TO PLAN A PROVINCIAL