Study on the Evaluation of the Firearms Directive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Complaint

Case 2:15-cv-05805-R-PJW Document 1 Filed 07/31/15 Page 1 of 66 Page ID #:1 1 C.D. Michel – Calif. S.B.N. 144258 Joshua Robert Dale – Calif. S.B.N. 209942 2 MICHEL & ASSOCIATES, P.C. 180 E. Ocean Blvd., Suite 200 3 Long Beach, CA 90802 Telephone: (562) 216-4444 4 Facsimile: (562) 216-4445 [email protected] 5 [email protected] 6 Attorneys for Plaintiff Wayne William Wright 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 FOR THE CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 WESTERN DIVISION - COURTHOUSE TBD 11 WAYNE WILLIAM WRIGHT, ) CASE NO. __________________ ) 12 Plaintiff, ) COMPLAINT FOR: ) 13 v. ) (1) VIOLATION OF FEDERAL ) CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER 14 CHARLES L. BECK; MICHAEL N. ) COLOR OF LAW FEUER; WILLIAM J. BRATTON; ) (42 U.S.C. §1983) 15 HEATHER AUBRY; RICHARD ) TOMPKINS; JAMES EDWARDS; ) (a) VIOLATION OF 16 CITY OF LOS ANGELES; and ) FOURTH DOES 1 through 50, ) AMENDMENT; 17 ) Defendants. ) (b) VIOLATION OF FIFTH 18 ) AMENDMENT; 19 (c) VIOLATION OF FOURTEENTH 20 AMENDMENT; 21 (2) STATE LAW TORTS OF CONVERSION & TRESPASS 22 TO CHATTELS; AND 23 (3) VIOLATION OF RACKETEER INFLUENCED AND 24 CORRUPT ORGANIZATIONS ACT 25 (18 U.S.C. §1961, et seq.) 26 (4) CONSPIRACY TO VIOLATE RACKETEER INFLUENCED 27 AND CORRUPT ORGANIZATIONS ACT 28 (18 U.S.C. §1962(d)) DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Case 2:15-cv-05805-R-PJW Document 1 Filed 07/31/15 Page 2 of 66 Page ID #:2 1 JURISDICTION AND VENUE 2 1. Jurisdiction of this action is founded on 28 U.S.C. -

List of Firearms Stolen from Residence 11/11/13-11/13/13 Medina County Sherrif Report No

List of Firearms Stolen from Residence 11/11/13-11/13/13 Medina County Sherrif Report No. 13-052372 Mfgr Model Cal. Action Barrel Finish Stock S/N Type Remarks Colt 1849 31 SA Oct B&C W 96869 Revolver In wood partitioned case Colt 1851 Navy 36 SA Oct B&C W 21943 Revolver NIB, 2nd gen., C-series, in wood grain carton Colt 1851 Navy 36 SA Oct B&C W 26226 Revolver NIB, 2nd gen., black carton, F1100 Colt 1851 Navy 36 SA Oct B&C W 24845 Revolver Dual cased set, 2nd gen., eng'd, gold band at muzzle, 3rd Dragoon 44 SA Round B&C W 24845 Revolver gold rampant colt on lug Colt 1862 Police 36 SA 6 1/2 B&C W 82413 Revolver NIB, Navy Arms reproduction Colt 3rd Dragoon 44 SA Round B&C W 22903 Revolver NIB w/papers, 2nd gen., C-series, in wood grain carton Colt Army 45 SA 7 1/2 Blue W 94535SA Revolver NIB w/papers, 2nd gen., Model P-1871, medallion grips Colt Army 38 Sp'l SA 5 1/2 B&C HR 357682 Revolver NIB, Prewar/Postwar, black carton Colt Army 38 Sp'l SA 5 1/2 B&C HR 357406 Revolver NIB, Prewar/Postwar, boxed Colt Frontier Scout 22 SA 4 3/4 Blue HR 76525F Revolver NIB Colt Frontier Scout 22 SA 4 3/4 Blue HR 219922F Revolver In French fit wood case Colt Frontier Scout 22 SA 4 3/4 Blue HR 185480F Revolver NIB, w/22mag cyl Colt Pre-Woodsman 22 Auto 6 Blue W 563XX Pistol Black boxed, w/target, booklet, papers, hang tag Colt Walker 44 SA 9 B&C W 14281 Revolver NIB San Marco Replica Arms reproduction Colt Walker 44 SA 9 B&C W 89358 Revolver NIB CVA reproduction, CVA Mod. -

Moving Forward EU-India Relations. the Significance of the Security

Moving Forward EU-India Relations The Significance of the Security Dialogues edited by Nicola Casarini, Stefania Benaglia and Sameer Patil Edizioni Nuova Cultura Output of the project “Moving Forward the EU-India Security Dialogue: Traditional and Emerging Issues” led by the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) in partnership with Gate- way House: Indian Council on Global Relations (GH). The project is part of the EU-India Think Tank Twinning Initiative funded by the European Union. First published 2017 by Edizioni Nuova Cultura for Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) Via Angelo Brunetti 9 – I-00186 Rome – Italy www.iai.it and Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations Colaba, Mumbai – 400 005 India Cecil Court, 3rd floor Copyright © 2017 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations (ch. 2-3, 6-7) and Istituto Affari Internazionali (ch. 1, 4-5, 8-9) ISBN: 9788868128531 Cover: by Luca Mozzicarelli Graphic composition: by Luca Mozzicarelli The unauthorized reproduction of this book, even partial, carried out by any means, including photocopying, even for internal or didactic use, is prohibited by copyright. Table of Contents Abstracts .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 15 1. Maritime Security and Freedom of Navigation from the South China Sea and Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean: -

501 Cmr: Executive Office of Public Safety

501 CMR: EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF PUBLIC SAFETY 501 CMR 7.00: APPROVED WEAPON ROSTERS Section 7.01: Purpose 7.02: Definitions 7.03: Development of Approved Firearms Roster 7.04: Criteria for Placement on Approved Firearms Roster 7.05: Compliance with the Approved Roster by Licensees 7.06: Appeals for Inclusion on or Removal from the Approved Firearms Roster 7.07: Form and Publication of the Approved Firearms Roster 7.08: Development of a Large Capacity Weapons Roster 7.09: Criteria for Placement on Large Capacity Weapons Roster 7.10: Large Capacity Weapons Not Listed 7.11: Form and Publication of the Large Capacity Weapons Roster 7.12: Development of the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.13: Criteria for Placement on the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.14: Appeals for Inclusion on the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.15: Form and Publication of the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.16: Severability 7.01: Purpose The purpose of 501 CMR 7.00 is to provide rules and regulations governing the inclusion of firearms, rifles and shotguns on rosters of weapons referred to in M.G.L. c. 140, §§ 123 and 131¾. 7.02: Definitions As used in 501 CMR 7.00: Approved Firearm means a firearm make and model that passed the testing requirements of M.G.L. c. 140, § 123 and was subsequently approved by the Secretary. Included are those firearms listed on the current Approved Firearms Roster and those firearms approved by the Secretary of Public Safety that will be included on the next published Approved Firearms Roster. -

California State Laws

State Laws and Published Ordinances - California Current through all 372 Chapters of the 2020 Regular Session. Attorney General's Office Los Angeles Field Division California Department of Justice 550 North Brand Blvd, Suite 800 Attention: Public Inquiry Unit Glendale, CA 91203 Post Office Box 944255 Voice: (818) 265-2500 Sacramento, CA 94244-2550 https://www.atf.gov/los-angeles- Voice: (916) 210-6276 field-division https://oag.ca.gov/ San Francisco Field Division 5601 Arnold Road, Suite 400 Dublin, CA 94568 Voice: (925) 557-2800 https://www.atf.gov/san-francisco- field-division Table of Contents California Penal Code Part 1 – Of Crimes and Punishments Title 15 – Miscellaneous Crimes Chapter 1 – Schools Section 626.9. Possession of firearm in school zone or on grounds of public or private university or college; Exceptions. Section 626.91. Possession of ammunition on school grounds. Section 626.92. Application of Section 626.9. Part 6 – Control of Deadly Weapons Title 1 – Preliminary Provisions Division 2 – Definitions Section 16100. ".50 BMG cartridge". Section 16110. ".50 BMG rifle". Section 16150. "Ammunition". [Effective until July 1, 2020; Repealed effective July 1, 2020] Section 16150. “Ammunition”. [Operative July 1, 2020] Section 16151. “Ammunition vendor”. Section 16170. "Antique firearm". Section 16180. "Antique rifle". Section 16190. "Application to purchase". Section 16200. "Assault weapon". Section 16300. "Bona fide evidence of identity"; "Bona fide evidence of majority and identity'. Section 16330. "Cane gun". Section 16350. "Capacity to accept more than 10 rounds". Section 16400. “Clear evidence of the person’s identity and age” Section 16410. “Consultant-evaluator” Section 16430. "Deadly weapon". Section 16440. -

The Restructuring and Conversion of the Bulgarian Defense Industry During the Transition Period

BONN INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR CONVERSION . INTERNATIONALES KONVERSIONSZENTRUM BONN paper 22 The Restructuring and Conversion of the Bulgarian Defense Industry during the Transition Period July 2002 BONN INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR CONVERSION . INTERNATIONALES KONVERSIONSZENTRUM BONN The Restructuring and Conversion of the Bulgarian Defense Industry during the Transition Period By Dimitar Dimitrov Published by BICC, Bonn 2002 The Restructuring and Conversion of the Bulgarian Defense Industry Table of Contents Acknowledgments 3 Introduction 4 Theoretical Background of the Study 6 Particular characteristics of socialist defense enterprises 11 Historical overview 12 The Defense Industry After WWII 13 The Defense Industry in the 1970s and 80s 16 Planning processes, state bodies and procedures during socialism 18 The Structure of the Bulgarian MIC 19 Initial Conditions for Transformation 23 The Restructuring of the Defense Industry 26 Factors and strategies for conversion 26 Organizational restructuring and downsizing 30 Product restructuring 36 Management and personnel restructuring 39 Privatization 40 State Policies and Regulations 46 State Defense Industrial Policy: Pros and Cons 46 Government Regulations and State Bodies 50 The Role of the MoD 54 The Arms trade 56 1 Dimitar Dimitrov R&D and Innovations 58 Foreign cooperation 62 The Conversion of Bulgaria’s Defense Industry 65 The Role of the State in the Conversion Process 67 The Background of Companies Slated for Conversion in Bulgaria 71 Conversion in the 1990s 74 What next? 78 Conclusion: -

“BULLET BUTTON” / “ASSAULT WEAPON” Quick Reference Guide

“BULLET BUTTON” / “ASSAULT WEAPON” quick Reference Guide PREREQUISITE FEATURES or telescoping stock, (D) A grenade launcher or the weapon without burning the bearer’s hand, QUICK TIPS OF AN ASSAULT WEAPON (AW) flare launcher, (E) A flash suppressor, or (F) A except a slide that encloses the barrel; (J) The FOR GUN OWNERS WITH The Penal Code now classifies the following as forward pistol grip. capacity to accept a detachable magazine at FIREARMS NOW an AW: PISTOLS: A semiautomatic pistol that does not some location outside of the pistol grip. have a fixed magazine but has anyone of the SHOTGUNS: While the change in the Penal CLASSIFIED AS RIFLES: A semiautomatic, centerfire rifle that following: (G) A threaded barrel, capable of ac- Code affects certain rifles and pistols, the DOJ does not have a fixed magazine but has any “ASSAULT WEAPONS” cepting a flash suppressor, forward handgrip, has taken the position that semiautomatic shot- one of the following: (A) A pistol grip that pro- or silencer; (H) A second handgrip; (I) A shroud guns required to be equipped with “bullet but- On January 1, 2017, the definition trudes conspicuously beneath the action of the that is attached to, or partially or completely en- tons” are also affected. of an “assault weapon” (“AW”) under weapon, (B) A thumbhole stock, (C) A folding California law was changed to include circles, the barrel that allows the bearer to fire firearms which were required to be equipped with a “bullet button” or similar KEY DEFINITIONS magazine locking device. This change does not affect ex- “FIXED MAGAZINE”- An ammunition feeding device contained in, or permanently attached to, a firearm in such a manner that the device cannot isting definitions of other types of AWs, be removed without disassembly of the firearm action. -

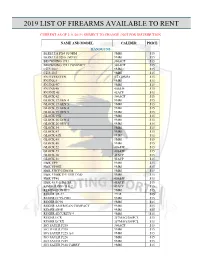

2019 List of Firearms Available to Rent

2019 LIST OF FIREARMS AVAILABLE TO RENT CURRENT AS OF 2/11/2019 | SUBJECT TO CHANGE | NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION NAME AND MODEL CALIBER PRICE HANDGUNS BERETTA PX4 STORM 9MM $15 BERETTA 92FS | M9A1 9MM $15 BROWNING 1911 380ACP $15 BROWNING 1911 COMPACT 380ACP $15 CZ P-10 C 9MM $15 CZ P-10 F 9MM $15 FN FIVESEVEN 5.7X28MM $15 FN FNS-9 9MM $15 FN FNS-9C 9MM $15 FN FNS-40 40S&W $15 FN FNX-45 45ACP $15 GLOCK 42 380ACP $15 GLOCK 17 GEN 4 9MM $15 GLOCK 17 GEN 5 9MM $15 GLOCK 19 GEN 4 9MM $15 GLOCK 19 GEN 5 9MM $15 GLOCK 19X 9MM $15 GLOCK 26 GEN 4 9MM $15 GLOCK 26 GEN 5 9MM $15 GLOCK 34 9MM $15 GLOCK 43 9MM $15 GLOCK 43X 9MM $15 GLOCK 45 9MM $15 GLOCK 48 9MM $15 GLOCK 22 40S&W $15 GLOCK 23 40S&W $15 GLOCK 36 45ACP $15 GLOCK 21 45ACP $15 H&K VP9 9MM $15 H&K VP9SK 9MM $15 H&K P30 V-3 DA/SA 9MM $15 H&K P30SK V-1 LEM DAO 9MM $15 H&K VP40 40S&W $15 H&K 45 V-1 DA/SA 45ACP $15 KIMBER PRO TLE 2 45ACP $15 REMINGTON RP9 9MM $15 RUGER SR-22 22LR $15 RUGER LC9S-PRO 9MM $15 RUGER EC9S 9MM $15 RUGER AMERICAN COMPACT 9MM $15 RUGER SR9E 9MM $15 RUGER SECURITY-9 9MM $15 RUGER LCR 357MAG/38SPCL $15 RUGER LCRX 357MAG/38SPCL $15 SIG SAUER P238 380ACP $15 SIG SUAER P938 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P225 A-1 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P226 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P229 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P320 CARRY 9MM $15 NAME AND MODEL CALIBER PRICE HANDGUNS SIG SAUER P320–M17 9MM 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P365 9MM $15 SMITH & WESSON M&P22 COMPACT 22LR $15 SMITH & WESSON REVOLVER 617 22LR $15 SMITH & WESSON BODYGUARD 380 380ACP $15 SMITH & WESSON M&P380 SHIELD EZ 380ACP $15 SMITH & WESSON M&P9 M2.0 5” FDE 9MM $15 SMITH & -

Guide on Firearms Licensing Law

Guide on Firearms Licensing Law April 2016 Contents 1. An overview – frequently asked questions on firearms licensing .......................................... 3 2. Definition and classification of firearms and ammunition ...................................................... 6 3. Prohibited weapons and ammunition .................................................................................. 17 4. Expanding ammunition ........................................................................................................ 27 5. Restrictions on the possession, handling and distribution of firearms and ammunition .... 29 6. Exemptions from the requirement to hold a certificate ....................................................... 36 7. Young persons ..................................................................................................................... 47 8. Antique firearms ................................................................................................................... 53 9. Historic handguns ................................................................................................................ 56 10. Firearm certificate procedure ............................................................................................... 69 11. Shotgun certificate procedure ............................................................................................. 84 12. Assessing suitability ............................................................................................................ -

Ziarul Financiar Ziarul Financiar

50% ISTORIE, UN CEO BOGAT 50% BUSINESS Robert Rekkers este unul dintre cei mai boga]i Pove[tile trecutului pot inspira un stil de via]`, bancheri din Romånia, de]inånd un pachet de dar [i o afacere. Citi]i \n Dup` Afaceri despre 0,6512% din ac]iunile B`ncii Transilvania, care farmecul unor locuri cu parfum interbelic. valoreaz` circa 11,6 mil. euro. Pagina 5 Ziarul Financiar EDITAT DE PUBLIMEDIA ANUL IX / NR. 2198 12+16+8 PAGINI VINERI, 10 AUGUST 2007 PRE}: 2,50 LEI WWW.ZF.RO MOL a pierdut 7% din cifra de afaceri ca urmare a schimbului cu Petrom MOL Romånia a pierdut din cota de pia]` prin vånzarea a 30 de benzin`rii, dar a cå[tigat la profit. ROXANA PETRESCU 11,4 milioane de euro. Spre deosebire de MOL [i Potrivit raportului la [ase luni emis de MOL „|n 2007, MOL Romånia va investi 15,4 Rompetrol, ru[ii de la Lukoil, de exemplu, au avut Ungaria, cota de pia]` a filialei din Romånia s-a milioane de euro pentru a-[i extinde re]eaua de iliala local` a grupului petrolier ungar afaceri cu 52% mai mari \n primul semestru al diminuat cu 1,2 puncte procentuale pån` la un benzin`rii cu 9 sta]ii, atåt prin investi]ii greenfield, MOL, a patra companie ca m`rime acestui an pån` la un nivel de 602 milioane de nivel 11,7% din cauza schimbului cu Petrom. De cåt [i prin achizi]ii. |n perioada 2008-2010, MOL ZF prezent` pe pia]a petrolier` local`, a euro. -

Small Arms of the Indian State: a Century of Procurement And

INDIA ARMED VIOLENCE ASSESSMENT Issue Brief Number 4 January 2014 Small Arms of the Indian State A Century of Procurement and Production Introduction state of dysfunction’ and singled out nuclear weapons (Bedi, 1999; Gupta, Army production as particularly weak 1990). Overlooked in this way, the Small arms procurement by the Indian (Cohen and Dasgupta, 2010, p. 143). Indian small arms industry developed government has long reflected the coun- Under this larger procurement its own momentum, largely discon- try’s larger national military procure- system, dominated by a culture of nected from broader international ment system, which stressed indigenous conservatism and a preference for trends in armament design and policy. arms production and procurement domestic manufacturers, any effort to It became one of the world’s largest above all. This deeply ingrained pri- modernize the small arms of India’s small arms industries, often over- ority created a national armaments military and police was held back, looked because it focuses mostly on policy widely criticized for passivity, even when indigenous products were supplying domestic military and law lack of strategic direction, and deliv- technically disappointing. While the enforcement services, rather than civil- ering equipment to the armed forces topic of small arms development ian or export markets. which was neither wanted nor suited never was prominent in Indian secu- As shown in this Issue Brief, these to their needs. By the 1990s, critics had rity affairs, it all but disappeared trends have changed since the 1990s, begun to write of an endemic ‘failure from public discussion in the 1980s but their legacy will continue to affect of defense production’ (Smith, 1994, and 1990s. -

Canada Gazette, Part II

EXTRA Vol. 154, No. 3 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 154, no 3 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part II Partie II OTTAWA, FRIDAY, MAY 1, 2020 OTTAWA, LE VENDREDI 1er MAI 2020 Registration Enregistrement SOR/2020-96 May 1, 2020 DORS/2020-96 Le 1er mai 2020 CRIMINAL CODE CODE CRIMINEL P.C. 2020-298 May 1, 2020 C.P. 2020-298 Le 1er mai 2020 Whereas the Governor in Council is not of the opinion Attendu que la gouverneure en conseil n’est pas d’avis that any thing prescribed to be a prohibited firearm or que toute chose désignée comme arme à feu prohibée a prohibited device, in the Annexed Regulations, is ou dispositif prohibé dans le règlement ci-après peut reasonable for use in Canada for hunting or sporting raisonnablement être utilisée au Canada pour la purposes; chasse ou le sport, Therefore, Her Excellency the Governor General in À ces causes, sur recommandation du ministre de la Council, on the recommendation of the Minister of Justice et en vertu des définitions de « arme à feu à Justice, pursuant to the definitions “non-restricted autorisation restreinte »1a, « arme à feu prohibée »a, firearm”1a, “prohibited device”2b, “prohibited firearm”b « arme à feu sans restriction »2b et « dispositif prohi- and “restricted firearm”b in subsection 84(1) of the bé »a au paragraphe 84(1) du Code criminel 3c et du Criminal Code 3c and to subsection 117.15(1)b of that paragraphe 117.15(1)a de cette loi, Son Excellence la Act, makes the annexed Regulations Amending the Gouverneure générale en conseil prend le Règlement Regulations Prescribing Certain Firearms and Other modifiant le Règlement désignant des armes à feu, Weapons, Components and Parts of Weapons, Acces- armes, éléments ou pièces d’armes, accessoires, char- sories, Cartridge Magazines, Ammunition and Project- geurs, munitions et projectiles comme étant prohibés, iles as Prohibited, Restricted or Non-Restricted.