3 Zarafshan Valley: Environment, Agriculture and the System of Livelihood Provision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Old Elites Under Communism: Soviet Rule in Leninobod a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Di

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OLD ELITES UNDER COMMUNISM: SOVIET RULE IN LENINOBOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY FLORA J. ROBERTS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ vi A Note on Transliteration .................................................................................................. ix Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One. Noble Allies of the Revolution: Classroom to Battleground (1916-1922) . 43 Chapter Two. Class Warfare: the Old Boi Network Challenged (1925-1930) ............... 105 Chapter Three. The Culture of Cotton Farms (1930s-1960s) ......................................... 170 Chapter Four. Purging the Elite: Politics and Lineage (1933-38) .................................. 224 Chapter Five. City on Paper: Writing Tajik in Stalinobod (1930-38) ............................ 282 Chapter Six. Islam and the Asilzodagon: Wartime and Postwar Leninobod .................. 352 Chapter Seven. The -

Analysis of the Situation on Inclusive Education for People with Disabilities in the Republic of Tajikistan Report on the Results of the Baseline Research

Public Organization - League of women with disabilities «Ishtirok» April - July 2018 Analysis of the situation on inclusive education for people with disabilities in the Republic of Tajikistan Report on the results of the baseline research 1 EXPRESSION OF APPRECIATION A basic study on the inclusive education of people with disabilities in the Republic of Tajikistan (RT) conducted by the Public Organization Disabled Women's League “Ishtirok”. This study was conducted under financial support from ASIA SOUTH PACIFIC ASSOCIATION FOR BASIC AND ADULT EDUCATION (ASPBAE) The research team expresses special thanks to the Executive Office of the President of the RT for assistance in collecting data at the national, regional, and district levels. In addition, we express our gratitude for the timely provision of data to the Centre for adult education of Tajikistan of the Ministry of labor, migration, and employment of population of RT, the Ministry of education and science of RT. We express our deep gratitude to all public organizations, departments of social protection and education in the cities of Dushanbe, Bokhtar, Khujand, Konibodom, and Vahdat. Moreover, we are grateful to all parents of children with disabilities, secondary school teachers, teachers of primary and secondary vocational education, who have made a significant contribution to the collection of high-quality data on the development of the situation of inclusive education for persons with disabilities in the country. Research team: Saida Inoyatova – coordinator, director, Public Organization - League of women with disabilities «Ishtirok»; Salomat Asoeva – Assistant Coordinator, Public Organization - League of women with disabilities «Ishtirok»; Larisa Alexandrova – lawyer, director of the Public Foundation “Your Choice”; Margarita Khegay – socio-economist, candidate of economic sciences. -

Tourism in Tajikistan As Seen by Tour Operators Acknowledgments

Tourism in as Seen by Tour Operators Public Disclosure Authorized Tajikistan Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized DISCLAIMER CONTENTS This work is a product of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS......................................................................i The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other INTRODUCTION....................................................................................2 information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. TOURISM TRENDS IN TAJIKISTAN............................................................5 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS TOURISM SERVICES IN TAJIKISTAN.......................................................27 © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank TOURISM IN KHATLON REGION AND 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: +1 (202) 522-2422; email: [email protected]. GORNO-BADAKHSHAN AUTONOMOUS OBLAST (GBAO)...................45 The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and li- censes, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, PROFILE AND LIST OF RESPONDENTS................................................57 Cover page images: 1. Hulbuk Fortress, near Kulob, Khatlon Region 2. Tajik girl holding symbol of Navruz Holiday 3. -

Cesifo Working Paper No. 5937 Category 4: Labour Markets June 2016

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Danzer, Alexander M.; Grundke, Robert Working Paper Coerced Labor in the Cotton Sector: How Global Commodity Prices (Don't) Transmit to the Poor CESifo Working Paper, No. 5937 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Danzer, Alexander M.; Grundke, Robert (2016) : Coerced Labor in the Cotton Sector: How Global Commodity Prices (Don't) Transmit to the Poor, CESifo Working Paper, No. 5937, Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/144972 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Coerced Labor in the Cotton Sector: How Global Commodity Prices (Don’t) Transmit to the Poor Alexander M. -

IOM Tajikistan Newsletter - June 2011

IOM Tajikistan Newsletter - June 2011 Legal Assistance to the Wives and Families of Labour Migrants 3 Strengthening Disaster Response Capacities of the Government 4 Ecological Pressures Behind Migration 5 Joint Trainings for Tajik and Afghan Border Guards 6 Roundtable on HIV/AIDS Prevention Along Transport Routes 7 Promoting Household Budgeting to Build Confidence for the Future 8 Training Tajik Officials in the Essentials of Migration Management 9 Monitoring Use of Child Labour in Tajikistan’s Cotton Harvest 10 2 January - June 2011 Foreword from the Chief of Mission Dear Readers, With the growing number of Tajik citizens working and IOM Tajikistan has allocated significant resources into living in the exterior, it has become difficult to over- the development of the knowledge and skills of gov- state the impact migration has had on Tajik society. ernmental officials and civil society groups throughout For those of us here in Tajikistan, the scope of the the country on the Essentials of Migration Manage- phenomenon goes without mention. For others, it is ment. worth considering that upwards of 1,000,000 Tajiks (of a total population estimated around 7,000,000) Only with the generous support of our donors and have migrated abroad, largely in search of employ- continued cooperation with our implementing part- ment. Their remittances alone account for 30-40% of ners is IOM able to provide the needed support to the national GDP, making the nation one of the most people of Tajikistan during these economically chal- dependent on remittance dollars in the world. lenging times. On behalf of the entire IOM Mission in Tajikistan, I would like to extend our highest gratitude This newsletter aims to present IOM Tajikistan’s activi- for their confidence. -

Annual Report

FUNDED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION IMPLEMENTED BY THE UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME With financial support from the Russian Federation ANNUAL REPORT ON IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS OF THE PROJECT “LIVELIHOOD IMPROVEMENT OF RURAL POPULATION IN 9 DISTRICTS OF THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN” FROM JANUARY 1 TO DECEMBER 31, 2017 Dushanbe 2017 1 Russian Federation-UNDP Trust Fund for Development (TFD) Project Annual Narrative and Financial Progress Report for January 1 – December 31, 2017 Project title: "Livelihood Improvement of Rural Population in 9 districts of the Republic of Tajikistan" Project ID: 00092014 Implementing partner: United Nations Development Programme, Tajikistan Project budget: Total: 6,700,000 USD TFD: Government of the Russian Federation: 6,700,000 USD Project start and end date: November 2014 – December 2017 Period covered in this report: 1st January to 31st December 2017 Date of the last Project Board 17th January 2017 meeting: SDGs supported by the project: 1, 2, 5, 8, 9, 10, 12 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Please provide a short summary of the results, highlighting one or two main achievements during the period covered by the report. Outline main challenges, risks and mitigation measures. The project "Livelihood Improvement of Rural Population in 9 districts of the Republic of Tajikistan", is funded by the Government of the Russian Federation, and implemented by UNDP Communities’ Program in the Republic of Tajikistan through its regional offices. Project target areas are Isfara, Istaravshan, Ayni, Penjikent in Sughd region; Vose and Temurmalik in Khatlon region; Rasht, Tojikobod and Lakhsh (Jirgatal) in the Districts of Republican Subordination (DRS). The main objective of the project is to ensure sustainable local economic development of the target districts of Tajikistan. -

Tajikistan Maternal and Child Health Program

Tajikistan Maternal and Child Health Program Quarterly Report #10 Reporting Period: January 1, 2011 - March 31, 2011 Cooperative Agreement # 119-A-00-08-00025-00 Submitted by: Mercy Corps –Tajikistan TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Acronyms and Abbreviation…………………………………………...………………. 3 2 Project Overview and Progress towards Objectives….………………………….….... 4 3 Status of Activities………………………………………………………………...……..7 3.1 Community Development…………………………………………...………......7 3.2 Behavior Change Communication (BCC)………………………..…………....8 3.3 Child-to-Child (CtC)………………………………………………...…………..9 3.4 Safe Motherhood…………………………………………………..………….…9 3.5 Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI)……………………….10 3.6 Water, Sanitation and Hygiene………………………………………….…….11 3.7 Monitoring & Evaluation activity……………………………………………..12 4 Planned vs. Actual Status of Activities………………………………………………..13 5 Constraints/Challenges…………………………………………………...……………14 6 Technical Assistance…………………………………………………...……………....14 7 Conferences/Workshops……………………………………………………………….14 8 Success Story: The man of the time………………………………………..………….15 2 | P a g e ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS ARI Acute Respiratory Infection BCC Behavior Change Communication CHE Community Health Educator CHL Centers for Promotion of Healthy Lifestyles C-IMCI Community Integrated Management of Childhood Illness CtC Child-to-Child DIP Detailed Implementation Plan DOH Department of Health – Sughd Oblast & District levels EPC Essential Prenatal Care ETS Emergency Transport System Feldsher Lowest level of healthcare worker, a medic FGD Focus Group -

Tajikistan 2017 International Religious Freedom Report

TAJIKISTAN 2017 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution provides for the right, individually or jointly with others, to adhere to any religion or to no religion, and to participate in religious customs and ceremonies. The constitution says religious organizations shall be separate from the state and “shall not interfere in state affairs.” The constitution bans political parties based on religion. The law restricts Islamic prayer to specific locations, regulates the registration and location of mosques, and prohibits persons under 18 from participating in public religious activities. The government’s Committee on Religious Affairs, Regulation of National Traditions, Celebrations, and Ceremonies (CRA)’s has a very broad mandate that includes approving registration of religious associations, construction of houses of worship, participation of children in religious education, and the dissemination of religious literature. The government continued to take measures to prevent individuals from joining or participating in what it considered to be “extremist” organizations, arresting or detaining more than 220 persons, primarily for membership in banned terrorist organizations and religious groups, including ISIS, “Salafis,” and Ansarrullah. Officials continued to prevent members of minority religious groups, including Jehovah’s Witnesses, from registering their organizations. Both registered and unregistered religious organizations continued to be subject to police raids, surveillance, and forced closures. Hanafi Sunni mosques continued to enforce a religious edict by the government-supported Council of Ulema prohibiting women from praying at mosques. The government jailed a Protestant pastor in the northern part of the country for “extremism” for possessing “unauthorized” religious literature. Sources stated authorities attempted to “maintain total control of Muslim activity” in the country. -

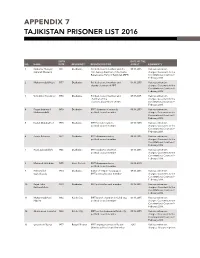

Appendix 7 Tajikistan Prisoner List 2016

APPENDIX 7 TAJIKISTAN PRISONER LIST 2016 BIRTH DATE OF THE NO. NAME DATE RESIDENCY RESPONSIBILITIES ARREST COMMENTS 1 Saidumar Huseyini 1961 Dushanbe Political council member and the 09.16.2015 Various extremism (Umarali Khusaini) first deputy chairman of the Islamic charges. Case went to the Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 2 Muhammadalii Hayit 1957 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.16.2015 Various extremism deputy chairman of IRPT charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 3 Vohidkhon Kosidinov 1956 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.17.2015 Various extremism chairman of the charges. Case went to the elections department of IRPT Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 4 Fayzmuhammad 1959 Dushanbe IRPT chairman of research, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Muhammadalii political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 5 Davlat Abdukahhori 1975 Dushanbe IRPT foreign relations, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 6 Zarafo Rahmoni 1972 Dushanbe IRPT chairman advisor, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 7 Rozik Zubaydullohi 1946 Dushanbe IRPT academic chairman, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 8 Mahmud Jaloliddini 1955 Hisor District IRPT chairman advisor, 02.10.2015 political council member 9 Hikmatulloh 1950 Dushanbe Editor of “Najot” newspaper, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Sayfullozoda IRPT political council member charges. -

Tajik Girls' Dilemma: Marriage Or Education?

Tajik Girls’ Dilemma: Marriage or Education? In Tajikistan, many girls are forbidden to continue their studies after high school graduation. It is believed that Tajik woman’s destiny is to get married, raise children, to take care of her husband and his parents. Therefore, for many girls, a diploma of higher education becomes an obstacle to family life. Subscribe to our Telegram channel! Educated daughters-in-law are especially undervalued in rural Tajikistan. There, it is assumed that educated girls turn out obstinate wives. It has been this way at all times, and many Tajiks still believe it now. 33-years-old Zulfia (not her real name) lives in the Gazantarak village of Devashtich district in northern Sughd region. She is a lawyer by profession and now raises her son alone. Despite the fact that she married for love, her family fell apart because her mother-in-law was reluctant to have an “educated daughter-in-law”. – On the third day after the wedding, the mother-in-law invited me outside. She was holding a long stick. “I don’t care if you are a lawyer or someone else. Starting from today, you will live according to the laws of my house. You will fulfill the norms I have set,” the mother-in-law told me. I did not understand the reasons for her antipathy to me then. Later she said that she wanted to marry off her son with a “homely, uneducated girl”. Tajik Girls’ Dilemma: Marriage or Education? Devashtich district, northern Sughd region of Tajikistan. Photo: CABAR.asia In many districts of the northern Sughd region, as well as throughout Tajikistan, it is customary to marry girls immediately after they reach the age of 18 or 19. -

Formative Research on Infant and Young Child Feeding

FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING Final Report AND MATERNAL NUTRITION 2016 IN TAJIKISTAN Conducted by Dornsife School of Public Health & College of Nursing and Health Professions, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA USA For UNICEF Tajikistan Under Drexel’s Long Term Agreement for Services In Communication for Development (C4D) with UNICEF And Contract # 43192550 January 11 through November 30, 2016 Principal Investigator Ann C Klassen, PhD , Professor, Department of Community Health and Prevention Co-Investigators Brandy Joe Milliron PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Nutrition Sciences Beth Leonberg, MA, MS, RD – Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Nutrition Sciences Graduate Research Staff Lisa Bossert, MPH, Margaret Chenault, MS, Suzanne Grossman, MSc, Jalal Maqsood, MD Professional Translation Staff Rauf Abduzhalilov, Shokhin Asadov, Malika Iskandari, Muhiddin Tojiev This research is conducted with the financial support of the Government of the Russian Federation Appendices : (Available Separately) Additional Bibliography Data Collector Training, Dushanbe, March, 2016 Data Collection Instruments Drexel Presentations at National Nutrition Forum, Dushanbe, July, 2016 cover page photo © mromanyuk/2014 FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING AND MATERNAL NUTRITION IN TAJIKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1: Executive Summary 5 Section 2: Overview of Project 12 Section 3: Review of the Literature 65 Section 4: Field Work Report 75 Section 4a: Methods 86 Section 4b: Results 101 Section 5: Conclusions and Recommendations 120 Section 6: Literature Cited 138 FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING 3 AND MATERNAL NUTRITION IN TAJIKISTAN AND MATERNAL NUTRITION IN TAJIKISTAN SECTION 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction Tajikistan is a mountainous, primarily rural country of approximately 8 million residents in Central Asia. -

RGP O2 Eval Report Final.Pdf

! ! Evaluation Output 2 Rural Growth Programme UNDP Republic of Tajikistan Evaluation Report Kris B. Prasada Rao Alisher Khaydarov Aug 2013 ! ! ! List%of%acronyms,%terminology%and%currency%exchange%rates% Acronyms AFT Aid for Trade AKF Aga Khan Foundation AO Area Office BEE Business Enabling Environment CDP Community Development Plan CO Country Office CP Communities Programme DCC Tajikistan Development Coordination Council DDP District Development Plan DFID Department for International Development DIM Direct Implementation Modality DP Development Plan GDP Gross Domestic Product GIZ Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GREAT Growth in the Rural Economy and Agriculture of Tajikistan HDI Human Development Index ICST Institute for Civil Servants Training IFC International Finance Corporation, the World Bank IOM International Organisation for Migration JDP Jamoat Development Plan LED Local Economic Development LEPI Local Economic Performance Indicator M&E Monitoring and Evaluation MEDT Ministry of Economic Development and Trade MC Mahalla Committee MoF Ministry of Finance MoU Memorandum of Understanding MSDSP Mountain Societies Development Support Programme MSME Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise NDS National Development Strategy NIM National Implementation Modality O2 Output 2, RGP O&M Operation and Maintenance ODP Oblast Development Plan: Sughd Oblast Social Economic Plan OECD/DAC Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Development Co-operation Directorate PEI UNDP-UNEP Poverty-Environment Initiative PPD Public-Private