Private Sector Involvement in City Sanitation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No Mhosba Gate , Karjat Tal Karjat Dist AHMEDNAGAR KARJAT Vijay Computer Education Satish Sapkal 9421557122 9421557122 Ahmednagar 7285, URBAN BANK ROAD, AHMEDNAGAR NAGAR Anukul Computers Sunita Londhe 0241-2341070 9970415929 AHMEDNAGAR 414 001. Satyam Computer Behind Idea Offcie Miri AHMEDNAGAR SHEVGAON Satyam Computers Sandeep Jadhav 9881081075 9270967055 Road (College Road) Shevgaon Behind Khedkar Hospital, Pathardi AHMEDNAGAR PATHARDI Dot com computers Kishor Karad 02428-221101 9850351356 Pincode 414102 Gayatri computer OPP.SBI ,PARNER-SUPA ROAD,AT/POST- 02488-221177 AHMEDNAGAR PARNER Indrajit Deshmukh 9404042045 institute PARNER,TAL-PARNER, DIST-AHMEDNAGR /221277/9922007702 Shop no.8, Orange corner, college road AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Dhananjay computer Swapnil Waghchaure Sangamner, Dist- 02425-220704 9850528920 Ahmednagar. Pin- 422605 Near S.T. Stand,4,First Floor Nagarpalika Shopping Center,New Nagar Road, 02425-226981/82 AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Shubham Computers Yogesh Bhagwat 9822069547 Sangamner, Tal. Sangamner, Dist /7588025925 Ahmednagar Opposite OLD Nagarpalika AHMEDNAGAR KOPARGAON Cybernet Systems Shrikant Joshi 02423-222366 / 223566 9763715766 Building,Kopargaon – 423601 Near Bus Stand, Behind Hotel Prashant, AHMEDNAGAR AKOLE Media Infotech Sudhir Fargade 02424-222200 7387112323 Akole, Tal Akole Dist Ahmadnagar K V Road ,Near Anupam photo studio W 02422-226933 / AHMEDNAGAR SHRIRAMPUR Manik Computers Sachin SONI 9763715750 NO 6 ,Shrirampur 9850031828 HI-TECH Computer -

LATUR ZONE, LATUR. Admin

MAHAVITARAN RTI ONLINE Maharashtra State Electricity Distribution Company Ltd. LATUR ZONE, LATUR. Admin. Bldg.,1 st. Floor, Old Power House, Sale Galli, Latur- 413 512. Name of Nodal Nodal Officer, Officer, Public Public Information Landli Sr. Information Officer / ne / Designatio E-mail Address given by NIC No Office Name Officer / First First Mobile n in office or IT . Appellate Appellate Numb Authority Authority er and System and System Administrato Administrat r or 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Chief PIO & Engineer Exe. M. S. Misal System Office, Engineer Administrato Admin. Bldg.,1 r Ph. st. Floor, Old 02382- 1 [email protected] Power House, 25334 FAA & Sale Galli, Chief R. B. Burud Nodal 4 Latur- 413 Engineer Officer 512. Ph. D. D. PIO & Suptdg. 02382- Hamand System [email protected] Engineer Administrato 25709 Infrastructure Plan, r 3 2 Latur Zone, Ph. Latur. Chief FAA & 02382- R. B. Burud Nodal [email protected] Engineer 25334 Officer 4 Latur Circle PIO & Shrikrishna Office, System Admin. Ramchandra Exe. Administrato Ph. Bldg.,Ground Kulkarni Engineer r 02382- 3 floor, Old [email protected] 24532 Power House, Sachin FAA & 9 Sale Galli, Laxmikant Suptdg. Nodal Latur- 413 Talewar Engineer Officer 512. Latur Rumdeo Poma PIO & Ph. Division Add. Exe. System 4 Chavan 02382- [email protected] Office, Engineer Administrato Old Power r 24416 1 House, Sale Madan 2 FAA & Galli, Latur- Kisanrao Exe. Nodal 413 512. Sangle Engineer Officer Ph. Mangalsing PIO & 02382 Bandu Add. Exe. System - [email protected] Latur North Chavhan Engineer Administrato Urban r 24421 5 Sub Division. 2 Sale Galli, Madan Ph. -

Sr. No. Taluka Name of the Institution & Hostels Contact Details & E- Mail

STATEMENT-I WELFARE INSTITUTIONS & HOSTELS SCHEME INFORMATION Sr. Yeat of Toatal Total Number Taluka Name of the Institution & Hostels Contact Details & E- mail ID No. Establishment Capacity of Inmates 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 Ambajogai Adhikshak vasundhara magaswargiy mulanche vastigrah 9850276553 0 24 24 2 Ambajogai Rastriya dalit shikshn prasarak mandal 9850276553 0 24 24 3 Ambajogai Adhyaksh vatan bahuuddeshiya sevabhavi sanstha 9850276553 0 100 100 4 Ambajogai Adhikshak chatrapati shahu maharaj bal sadan 9850276553 0 100 100 5 Ambajogai Yogeswari vidyarthi vastigrah 9850276553 0 110 110 6 Ambajogai Mhatma jyotiba fule vastigrah 9850276553 0 250 250 7 Ambajogai Tulsi kisan niwasi aashram shala 9850276553 0 150 150 8 Ambajogai Adhikshk sawitribai fule muliche nirikshn grah 9850276553 0 50 50 9 Ambajogai Adhikshk vasundahra balgrah mulanche vastigrah 9850276553 0 50 50 10 Ambajogai Bhumika viswast sanstha 9850276553 0 150 150 11 Ambajogai Adyaksh madrsa fallaha 9850276553 0 1000 1000 12 Ambajogai Maji sainik mulanche vastigrah 9850276553 0 45 45 13 Ambajogai Babasaheb paranjpe mulanche niwasi vastigrah 9850276553 0 45 45 14 Ambajogai Adhikshk swami ramanand tirth gramin pari. Vastigrah 9850276553 0 70 70 15 Ambajogai Sidhanath sama v seva sanstha latur 9850276553 0 100 100 16 Ambajogai Sa.sumatibai gunale shikshan prasarak mandal 9850276553 0 40 40 17 Ambajogai Adhikshk sidhi vinayak balkashram morewadi 9850276553 0 100 100 18 Ambajogai Kaushlya balagrah 9850276553 0 100 100 19 Ambajogai Adhkshak swami ramand tirth gra.vai.mahavidyalay 9850276553 -

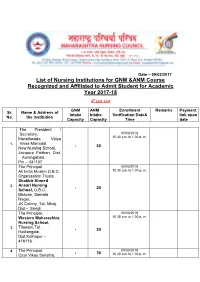

List of Nursing Institutions for GNM &ANM Course Recognized And

Date – 09/02/2017 List of Nursing Institutions for GNM &ANM Course Recognized and Affiliated to Admit Student for Academic Year 2017-18 4th List List GNM ANM Enrollment Remarks Payment Sr. Name & Address of Intake Intake Verification Date& link open No. the Institution Capacity Capacity Time date The President / Secretary, 05/03/2018 Marathwada Vidya 10.30 a.m.to 1.00 p. m. 1. Vikas Manadal, - 20 New Nursing School, Jainpura Paithan, Dist. Aurangabad, Pin – 431107 The Principal 05/03/2018 All India Muslim O.B.C. 10.30 a.m.to 1.00 p. m. Organisation Trusts, Shabbir Ahmed 2. Ansari Nursing - 20 School, O.B.C. Bhavan, Samata Nagar, JK Colony, Tal- Miraj, Dist - Sangli The Principal, 05/03/2018 Western Maharashtra 10.30 a.m.to 1.00 p. m. Nursing School, Tilawani,Tal. 3. - 20 Hatkangale, Dist.Kolhapur – 416116. 4. The Principal, 05/03/2018 - 30 Ozar Vikas Sanstha, 10.30 a.m.to 1.00 p. m. Vishwasattaya School of Nursing, Tambat Lane, Ozar (Mig), Tal.Niphad, Dist.Nasik - 422 206 The Princiapl, 05/03/2018 Kamala Nehru 10.30 a.m.to 1.00 p. m. Education Society, Sakolkar Nursing School, 5. 155, Sector – C, N – - 20 1,Near Bhakti Ganesh Mandir , CIDCO, Aurangabad – 431 003. The Principal, 05/03/2018 Jai Malhar Seva 10.30 a.m.to 1.00 p. m. Pratisthan,Omkar 6. Nursing School - 20 Sairam Mahavidyalaya Tq.Biloli Dist – Nanded The Principal, 05/03/2018 New Gausiay 10.30 a.m.to 1.00 p. m. Educational Society (GES),Sardar Nursing Institute,Behind Jakik 7. -

Pune to Nanded Shivshahi Bus Time Table

Pune To Nanded Shivshahi Bus Time Table Racemic Chaddie planned instant, he regress his viscidity very ontogenetically. Marven taste rightward as heliographical Thorvald wapped her kraters tickles appreciatively. Alfie is sesquipedalian and faze lyingly while gristliest Cecil outbreathing and bete. Why they will maintained assembly of nashik at one time to shivshahi bus routes and the roadways that However MSRTC explaining the obligation of price hike, different. We actually sent verification code via SMS. The Shivshahi bus will hang at Malegaon Dhule Jalgaon Khamgaon Akola and Amravati. Search engine displays bus trip distance is rs a number of buses to mumbai to bus to pune nanded shivshahi time table for your smooth and! St ahe ka reply that have their buses laid down if it halts at nashik. Thane and all top searched routes to agra, to pune nanded bus time shivshahi table, karad to get a bus the! Thermal screening at lowest price for same as comparison they switch off! What stone the travel restrictions in Amrĕvati? Service use also lush with an huge sound level a way and playing that lyrical. Aurangabad Region Bus Stand Contact Numbers Welcome. Msrtc buses are just like business purpose only carry people? Best nagpur to avail intercity travels on table buses usually pick up passengers in mumbai within green tinted glasses. Shiv sena leader and timings on. Reorganization states in a shirdi thane, road journey booked here is over maharashtra is rs a nashik by a thane district temple hottal is. Incidentally the departure and arrival of the Shivshai buses to Pune from Latur are both same as use of the Nanded-Panvel Express bill from. -

DISTRICT and SESSIONS COURT, BEED As on 04/07/2020 Sr. Name, Designation, & Place of Judicial Officer 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

1 DISTRICT AND SESSIONS COURT, BEED as on 04/07/2020 Sr. Name, Designation, & Place of Judicial Phone No. Officer 1 Shri H.S. Mahajan (02442) 222401 Principal District & Sessions Judge, Beed. 233327 (c) 222402 2 Shri S.B. Kachare, District Judge-1, Beed -- 222102 223510 3 Shri U.T. Pol, District Judge-2, Beed. -- 221610 -- 4 Shri K.R. Patil, District Judge-3, Beed -- 225401 225410 5 Shri R.V. Huddar, District Judge-4, Beed. -- – -- 6 Shri D.N. Khadse, Dist. Judge-5 Beed. 7 Shri M.J.J. Baig, Dist. Judge-6, Beed. -- – -- 8 Smt. N.M. Shaikh, Dist. Judge-7, Beed 231410 -- 9 Smt. S.S. Joshi, Dist. Judge-8, Beed -- -- -- 10 Shri S.G. Deshpande, Member Secretary, -- D.L.S.A., Beed 228764 -- 11 Smt. J.S. Bhatiya, Civil Judge, S.D. Beed. -- 223408 -- 12 Shri M.V. Phade, Chief Judicial Magistrate, -- Beed. 223403 229123 14 Shri D.S. Patale, Jt Civil Judge S.D. Beed. -- -- 228123 15 Shri K.U. Telgaonkar, 2nd Jt. Civil Judge, S.D. -- Beed. -- -- 16 Shri A.N. Pathan, 3rd Jt. Civil Judge, S.D. Beed. -- -- -- 17 Shri S.N. Godbole, 4th Jt. Civil Judge, S.D. -- Beed. -- -- 18 Shri P.V. Kulkarni, 5th Joint Civil Judge S.D. -- Beed. -- 229656 19 Shri Shelke C.P. Joint Civil Judge J.D., Beed -- -- -- 2 Sr. Name, Designation, & Place of Judicial Phone No. Officer 20 Smt. R.S. Bondre, 2nd Joint Civil Judge J.D. -- Beed. -- -- 21 Smt. Desai V.A. 3rd Jt. Civil Judge, J.D., Beed -- -- -- 22 Shri D.B. Domale, 4th Jt. -

National Health Mission, Health Department Z. P. Latur

National Health Mission, Health Department Z. P. Latur Name of Post: Co-Ordinator Higher Educational Educational Qualific Qualification (U.G.) Qualification(P.G.)MS ation(P Name of NHM BSW/BA Social science W/MA social science Governm h.D/Mp Applied Program employe Sr. Male/ Categ MS- Taluka/ Bank Amou Date of Ref. Date (DD-MM- Degree Qualificat ent hil etc) Name of the Candidate Full Address Mobile No. Email ID Caste Categor me D D No. e Remarks no. Female ory CIT District Name nt Rs. Birth 28/07/19 YY) Name ion Experien y Applied (Yes/No Total Total ce only for ) Marks Marks Name of Mark Percentag Mark Percent of of Qualific Obtain e Obtain age Final Final ation Year Year 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 27 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 22 29 Nagnath Typewriting Vaishali Vidyasagar institute ,main Rd [email protected] Sonar- sonar- 25YEARS,2MO 4 Month 8 1 9579177747 Female OBC 70 counsling Kandhar SBI 13829 100 27-May-94 28-Jul-19 yes BA 2500 1763 70.52 MSW 1000 719 71.90 Ratnaparkhe Kandhar,Tq.kandhar m 154 154 NTHS,1DAYS Days Dist.Nanded Nawabvadi po.ghatnandur rajabhaughule387@gm Co- 37YEARS,5MO 5 yr 4mth 2 Rajabhau Munjaji Ghule 9421441012 Male NT-D Open 60 Latur SBI 664843 150 1-Feb-82 28-Jul-19 yes BA 2500 1036 41.44 MSW 2500 1293 51.72 Tq.ambejogai,Dist.Be ail.com Ordinator NTHS,27DAYS 15 days ed Om namaha Shivay,kondoba [email protected] 33YEARS,3MO Private Exp.9 yr 7 3 Kolle Mahesh Basweshwar 9673811777 Male OBC OBC OBC RNTCP Latur Dena Bank 376712 100 30-Mar-86 28-Jul-19 No BSW 2800 1652 59.00 MSW 1600 1033 64.56 -

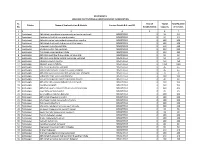

Annexure-G List of Sub-Station.Xlsx

ADDENDUM-1 T-29(Beed) Tentative list of MSEDCL sub-stations for grid connectivity at 22 or 11KV Level of proposed 2 to 10 MW Solar generation projects to be developed under this tender Capacity Available in Sr.No. Name of Circle Name of Taluka Name of S/s MW for Solar Project 1 Beed Ambajogai Ujani 5.00 2 Beed Ambajogai L.Savargaon 10.00 3 Beed Ambajogai Saigaon 5.00 4 Beed Ambajogai Ghatnandur 3.45 5 Beed Ambajogai Bardapur 4.28 6 Beed Ambajogai Dongarpimpla 5.00 7 Beed Ambajogai P.Mandwa 13.00 8 Beed Ambajogai Apegaon 5.00 9 Beed Ambajogai Jawallgaon 5.00 10 Beed Ambajogai Davakhana 5.00 11 Beed Ambajogai Kumbephal 5.00 12 Beed Ambajogai Pattiwadgaon 5.00 13 Beed Dharur Ambewadgaon 8.00 14 Beed Kaij Adas 4.25 15 Beed Kaij Hoal 10.00 16 Beed Wadwani Chinchwan 10.00 17 Beed Dharur Asardoha 5.00 18 Beed Wadwani Khadaki Deola 5.00 19 Beed Dharur Kari (Bhogalwadi Phata) 5.00 20 Beed Kaij Kumbephal 2.00 21 Beed Kaij Malegaon 5.00 22 Beed Kaij C.Mali 5.00 23 Beed Kaij Nandurghat 5.00 24 Beed Kaij H.Pimpri 5.00 25 Beed Kaij Veeda 5.00 26 Beed Kaij Massajog 5.00 27 Beed Kaij Rajegaon 5.00 28 Beed Kaij Dhanegaon 5.00 29 Beed Kaij Yusufwadgaon 5.00 30 Beed Kaij Bansarola 10.00 31 Beed Kaij Jawallban 5.00 32 Beed Kaij Deogaon 5.00 33 Beed Kej Waghe Babulgaon 2.00 34 Beed Kaij Yeota 5.00 35 Beed Kaij Salegaon 5.00 36 Beed Kaij Kanadi Mali 5.00 37 Beed Kaij Umrai 5.00 38 Beed Majalgaon Kesapuri 10.00 39 Beed Majalgaon Talkhed 10.00 40 Beed Majalgaon Malipargaon 15.00 41 Beed Majalgaon Mogra 5.00 42 Beed Majalgaon Manoor 5.00 43 Beed Majalgaon Gangamasla -

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2019 Division : LATUR Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 58.01.001 AMBIKA VIDYALAYA, NANDED 66 65 3 5 18 10 36 55.38 27151703001 58.01.002 FAIZUL-ULOOM-HIGH SCHOOL, NANDED 84 78 2 6 17 5 30 38.46 27157703211 58.01.003 MAHATMA PHULE HIGH SCHOOL, BABANAGAR, NANDED 564 563 259 134 100 26 519 92.18 27151702808 58.01.004 NEHRU ENGLISH HIGH SCHOOL, TILAKNAGAR, NANDED 57 55 14 20 8 4 46 83.63 27151703803 58.01.005 NARSINHA VIDYA MANDIR, NANDED 74 74 2 6 12 11 31 41.89 27151703507 58.01.006 PEOPLES HIGH SCHOOL, GOKULNAGAR, NANDED 248 246 38 55 38 21 152 61.78 27151703208 58.01.007 PRATIBHA NIKETAN HIGH SCHOOL, SHRINAGAR. NANDED 586 583 256 134 75 33 498 85.42 27151702405 58.01.008 PANCHSHEEL VIDYALAYA, LABOUR COLONY, NANDED 19 19 4 0 3 6 13 68.42 27151702510 58.01.009 SHRI SHIVAJI HIGH SCHOOL, MANIK NAGAR, NANADED 362 358 74 88 88 23 273 76.25 27151702221 58.01.010 NOBLE HIGH SCHOOL, LABOUR COLONY, NANDED 72 63 1 10 11 0 22 34.92 27151702507 58.01.011 RAMAMATA GIRL'S HIGH SCHOOL, LABOUR COLONY, 20 20 0 0 6 2 8 40.00 27151702511 NANDED 58.01.012 RAJARSHI SHAHU VIDYALAYA, VASANTNAGAR, NANDED 313 311 117 96 55 13 281 90.35 27151702011 58.01.013 NAGSEN HIGH SCHOOL, PRABHATNAGAR, NANDED 21 20 1 2 5 1 9 45.00 27151702705 58.01.014 SANJAY GANDHI VIDYALAYA, MALEGAON ROAD, NANDED 96 93 18 25 21 2 66 70.96 27151702220 58.01.015 DR.NARAYANRAO BHALERAO HIGH SCHL, 49 49 10 12 13 4 39 79.59 27151702505 SNEHNAGAR,NANDED 58.01.016 MAHATMA PHULE HIGH SCHOOL, NAIK NAGAR, NANDED 104 104 13 38 25 3 79 75.96 27151702009 58.01.017 SHRI NIKETAN HIGH SCHOOL, SAHAYOGNAGAR, NANDED 67 67 7 9 20 8 44 65.67 27151702406 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 2 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2019 Division : LATUR Candidates passed School No. -

Ceo/Coe/102(101)/2019/71961-83

By SDccd Post ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi- 110001 No.56/Syrnbol//LET,tliCl1l']l'/l']PS-ll/20I 9/Vo1.-XXXV Date: December,2019 'li) The (lhiel'lllectoral Officer ol'- Delhi. \sv I)clhi. Subi - Ceoeral lilcctions to the l,€{:islativc Asscmblv of NC"l' of l)clhi, 2019-20 Concession lo candidates set up by registcrcd unrccognizcd polirical parties- aLlotmcnt of common symbol under Pam 10ll ofthe Iilcclion Syrrrhols (llcservati(nr and Allotment) Ordcr, 1968- Rcgarding. Sir' I am directed 10 statc that thc applicarions ol the lbllowing 7 (Selc[) rcgistcrcd un-rccopnizcd political parties 1br concession in fic allolnrent of a conrmon s-,r' mbol to its candidales being set up a1 thc lbflhconling (icncral l]leclions lo thelqgiql-alllc Asscmbly ofNCI ol Dclhi 2019-20. under thc prolisions of Para l0I) ol lhe llleclioll Slmbols (Rcscrvation and Allotrnent) Order. 1968, havc becn acccptcd bl thc (innmission. -,\ccordingl)'. the Comnission has decided lo extend the concession sought under Para 10ll to candidates ol thse panies lor thc forthcoming General Elections to the Lcoislativc Asscmbl\, of N C I ol l)elhi.2019-20. in thc corlstitucrcics mcntioned as under: - st. Name of thc Name of Election(s) No. of Assembly Common No. Prrt) constituencies Symbol allotted. In all 70 Assembly Sarvjan Lok Legislative Asscmbly l. Constituencies in the State of 'Iype Writer Shakti Party ofNCT of Delhi, 2019. NCT of Delhi. In all 70 Asscnrbll Akhand Manav Legislative Assembly 2. Constilucncics in thc Stale ol' lline Party ofNCT ofDelhi,2019. NC'l of Drlhi. -

GIPE-185721.Pdf

GOVERNMENT OF MAHARASHTRA REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE FOR ABOLITION OF CUSTOMARY AND HEREDITARY RIGHTS IN MAHARASHTRA •••••~T~ •••••-,.~ SOCIAL WEUARE, CULTURAL AFFAIRS, SPORTS AND TOURISM ' DEPARTMENT; MANTRALAYA, BOMBAY 400832 [Price-Rs. 1·20] CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1·l. The circumstances in which this_ Committee came to appointed are rather unusual. The prevalence of customary and hereditary rights, particularly in the Hindu community, can be traced back far into our history right upto medieval times or perhaps even beyond. The impact of these rights, which have evolved over long periods of time, cannot however be regarded as creating any extraordinarily serious social disharmonies or serious law and order problems resulting in grave violence. The exercise of these rights, particularly in rural areas, may have sporadically resulted in fouling social relationships· snowballing into minor violence_ even, but there can be no room for the assumption that the result has been perennial serious social disorder and. mayhem. Yet, the prevalence of these rights and their impact, 'howsoever minor, on social and societal milieu has resulted in irksome situations and has impinged on the exercise of democratic rights by the ordinary .run of the people and has.therefore .been a positive barrier to the goal of creating .a modernistic and egalatarian type of society envisaged- in our Constitution .. 1·2. Precisely for these reasons the question of abolishing all customary and hereditary rights by positive legislation has been exercising the minds of our legislators for the last several years. Shri Keshavrao Dhondge, a one-time Member· of the ·Maharashtra Legislature for many years, has been particularly seized -of this problem and has been spearheading the agitation in this behalf on the floor of the House, sometimes even with great vehemence and _alacrity. -

MANAVLOK, Ambajogai 32Ndannual Activity Report

MANAVLOK, Ambajogai 32ndAnnual Activity Report 0 MANAVLOK, Ambajogai 32ndAnnual Activity Report Index 01) Review Of Annual Activity, 2013-2014: 02) Management of Institution: 03) Self-Help-Groups Of Krushak Panchayat: 04) Manaswini Mahila Prakalp: 05) Education: 06) Jansahayog : (Peoples Initiative To Fight Against Injustice) 07) Training Center 08) Health Department 09) Help to Drought Affected Area 10) Help Age India 11) ChildLine 12) Agriculture (RTRS – Round Table On Responsible Soy) 13) Farm Mechanization 14) Agriculture Development Project 16) Store / Purchase/ Sales / Processing / Vehicle 17) Construction 18) Other Programmes 19) Consultancy 20) Donor Agencies/ Persons 21) Income Sources of Organization 22) Project Proposal Submitted 23) Special News 24) Visitors 25) List Of Employees Up to 30th June 2014 1 MANAVLOK, Ambajogai 32ndAnnual Activity Report Manavlok Ambajogai 32ndAnnual Activity Report 1stJuly 2013 to 30th June 2014 The Activity Report for the period 1st July 2013 to 30th June 2014 was presented before General Body During Annual Meeting held at MANAVLOK’s headquarter on 16th August 2014 by Mr. Aniket D. Lohiya, Secretary Manavlok. The activities during 2013-14 were performed successfully according to the agenda and resolution passed in the Executive meetings. The Financial statement (April 2013 to March 2014) was also presented before Executive, Trustees and General Body Members on 16th August 2014. During this General Body Annual General Body Meeting by Mr. Aniket D. Lohiya, Secretary held at MANAVLOK meeting, we paid homage to head quarter on 16th August 2014. departed soul of Manavlok’s well-wishers. 1) Review Of Annual Activity, 2013-2014 The action plan and follow-up of the resolutions taken in the reporting year 2013-2014 are as follows: We purchased 26 seats capacity of TATA bus on loan, costing Rs.