Vigilantism Against Migrants and Minorities; First Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Parliament: 7Th February 2017 Redistribution of Political Balance

POLICY PAPER European issues n°420 European Parliament: 7th February 2017 redistribution of political balance Charles de Marcilly François Frigot At the mid-term of the 8th legislature, the European Parliament, in office since the elections of May 2014, is implementing a traditional “distribution” of posts of responsibility. Article 19 of the internal regulation stipulates that the Chairs of the parliamentary committees, the Deputy-Chairs, as well as the questeurs, hold their mandates for a renewable 2 and a-half year period. Moreover, internal elections within the political groups have supported their Chairs, whilst we note that there has been some slight rebalancing in terms of the coordinators’ posts. Although Italian citizens draw specific attention with the two main candidates in the battle for the top post, we should note other appointments if we are to understand the careful balance between nationalities, political groups and individual experience of the European members of Parliament. A TUMULTUOUS PRESIDENTIAL provide collective impetus to potential hesitations on the part of the Member States. In spite of the victory of the European People’s Party (EPP) in the European elections, it supported Martin As a result the election of the new President of Schulz in July 2104 who stood for a second mandate as Parliament was a lively[1] affair: the EPP candidate – President of the Parliament. In all, with the support of the Antonio Tajani – and S&D Gianni Pittella were running Liberals (ADLE), Martin Schulz won 409 votes following neck and neck in the fourth round of the relative an agreement concluded by the “grand coalition” after majority of the votes cast[2]. -

A Case of Youth Activism in Matica Slovenská

65 ETHNOLOGIA ACTUALIS Vol. 15, No. 1/2015 MARTIN PRIE ČKO Between Patriotism and Far-Right Extremism: A Case of Youth Activism in Matica slovenská Between Patriotism and Far-Right Extremism: A Case of Youth Activism in Matica slovenská MARTIN PRIE ČKO Department of Ethnology and World Studies, University of SS. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava [email protected] ABSTRACT This case study discusses a youth branch of Matica slovenská, a pro-Slovak culture organization. It is based on in-depth research of the structure of the organization and it focuses on basic characteristics of functioning of this social movement such as funding, membership base, political orientation, civic engagement, patriotic activities and also the causes of negative media presentation. Presented material pointed to a thin boundary between the perception of positive manifestations of patriotism and at the same time negative (even extremist) connotations of such manifestations in Slovak society. This duplicate perception of patriotic activities is reflected not only in polarization of opinion in society but also on the level of political, media and public communication. Thus, the article is a small probe from the scene of youth activism with an ambition to point out to such a diverse perception of patriotic organizations/activities in present-day Slovak society. KEY WORDS : Matica slovenská, youth, activism, state-supported organisation, patriotism, Far-Right Introduction Young Matica (MM – Mladá Matica) represents a subsidiary branch of Slovak Matica (MS – Matica slovenská), which is a traditional cultural and enlightenment organisation with DOI: 10.1515/eas-2015-0009 © University of SS. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava. -

2019 European Elections the Weight of the Electorates Compared to the Electoral Weight of the Parliamentary Groups

2019 European Elections The weight of the electorates compared to the electoral weight of the parliamentary groups Guillemette Lano Raphaël Grelon With the assistance of Victor Delage and Dominique Reynié July 2019 2019 European Elections. The weight of the electorates | Fondation pour l’innovation politique I. DISTINGUISHING BETWEEN THE WEIGHT OF ELECTORATES AND THE ELECTORAL WEIGHT OF PARLIAMENTARY GROUPS The Fondation pour l’innovation politique wished to reflect on the European elections in May 2019 by assessing the weight of electorates across the European constituency independently of the electoral weight represented by the parliamentary groups comprised post-election. For example, we have reconstructed a right-wing Eurosceptic electorate by aggregating the votes in favour of right-wing national lists whose discourses are hostile to the European Union. In this case, for instance, this methodology has led us to assign those who voted for Fidesz not to the European People’s Party (EPP) group but rather to an electorate which we describe as the “populist right and extreme right” in which we also include those who voted for the Italian Lega, the French National Rally, the Austrian FPÖ and the Sweden Democrats. Likewise, Slovak SMER voters were detached from the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) Group and instead categorised as part of an electorate which we describe as the “populist left and extreme left”. A. The data collected The electoral results were collected list by list, country by country 1, from the websites of the national parliaments and governments of each of the States of the Union. We then aggregated these data at the European level, thus obtaining: – the number of individuals registered on the electoral lists on the date of the elections, or the registered voters; – the number of votes, or the voters; – the number of valid votes in favour of each of the lists, or the votes cast; – the number of invalid votes, or the blank or invalid votes. -

International Migration in the Czech Republic and Slovakia and the Outlook for East Central Europe

International Migration in the Czech Republic and Slovakia and the Outlook for East Central Europe DUŠAN DRBOHLAV* Faculty of Science, Charles University, Prague Abstract: The contribution is devoted to the international migration issue in the Czech Republic and Slovakia (Czechoslovakia). Besides the contemporary trends, the international migration situation is briefly traced back to the communist era. The probable future scenario of international migration development - based especially on migration patterns that Western Europe has experienced - is also sketched, whilst mainly economic, social, political, demographic, psychological and geographical aspects are mentioned. Respecting a logical broader geopolitical and regional context, Poland and Hungary are also partly dealt with. Statistics are accompanied by some explanations, in order to see the various „faces“ of international migration (emigration versus immigration) as well as the different types of migration movements namely illegal/clandestine, legal guest-workers, political refugees and asylum seekers. Czech Sociological Review, 1994, Vol. 2 (No. 1: 89-106) 1. Introduction The aim of the first part of this contribution is to describe and explain recent as well as contemporary international migration patterns in the Czech Republic and Slovakia (and the former Czechoslovakia). The second part is devoted to sketching a possible future scenario of international migration development. In order to tackle this issue Poland and Hungary have also been taken into account. In spite of the general importance of theoretical concepts and frameworks of international migration (i.e. economic theoretical and historical-structural perspectives, psychosocial theories and systems and geographical approaches) the limited space at our disposal necessitates reference to other works that devote special attention to the problem of discussing theories1 [see e.g. -

United We Stand, Divided We Fall: the Kremlin’S Leverage in the Visegrad Countries

UNITED WE STAND, DIVIDED WE FALL: THE KREMLIN’S LEVERAGE IN THE VISEGRAD COUNTRIES Edited by: Ivana Smoleňová and Barbora Chrzová (Prague Security Studies Institute) Authors: Ivana Smoleňová and Barbora Chrzová (Prague Security Studies Institute, Czech Republic) Iveta Várenyiová and Dušan Fischer (on behalf of the Slovak Foreign Policy Association, Slovakia) Dániel Bartha, András Deák and András Rácz (Centre for Euro-Atlantic Integration and Democracy, Hungary) Andrzej Turkowski (Centre for International Relations, Poland) Published by Prague Security Studies Institute, November 2017. PROJECT PARTNERS: SUPPORTED BY: CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 CZECH REPUBLIC 7 Introduction 7 The Role of the Russian Embassy 7 The Cultural Sphere and Non-Governmental Organizations 8 The Political Sphere 9 The Extremist Sphere and Paramilitary Groups 10 The Media and Information Space 11 The Economic and Financial Domain 12 Conclusion 13 Bibliography 14 HUNGARY 15 Introduction 15 The Role of the Russian Embassy 15 The Cultural Sphere 16 NGOs, GONGOs, Policy Community and Academia 16 The Political Sphere and Extremism 17 The Media and Information Space 18 The Economic and Financial Domain 19 Conclusion 20 Bibliography 21 POLAND 22 Introduction 22 The Role of the Russian Embassy 22 Research Institutes and Academia 22 The Political Sphere 23 The Media and Information Space 24 The Cultural Sphere 24 The Economic and Financial Domain 25 Conclusion 26 Bibliography 26 SLOVAKIA 27 Introduction 27 The Role of the Russian Embassy 27 The Cultural Sphere 27 The Political Sphere 28 Paramilitary organisations 28 The Media and Information Space 29 The Economic and Financial Domain 30 Conclusion 31 Bibliography 31 CONCLUSION 33 UNITED WE STAND, DIVIDED WE FALL: THE KREMLIN’S LEVERAGE IN THE VISEGRAD COUNTRIES IN THE VISEGRAD THE KREMLIN’S LEVERAGE DIVIDED WE FALL: UNITED WE STAND, INTRODUCTION In the last couple of months, Russian interference in the internal affairs if the Kremlin’s involvement is overstated and inflated by the media. -

Esamizdat 2010-2011 08 Txt.Pdf

eSamizdat eSamizdat - (VIII) dicembre eSamizdat, Rivista di culture dei paesi slavi registrata presso la Sezione per la Stampa e l’Informazione del Tri- bunale civile di Roma. No 286/2003 del 18/06/2003, ISSN 1723-4042 Copyright eSamizdat - Alessandro Catalano e Simone Guagnelli DIRETTORE RESPONSABILE Simona Ragusa CURATORI Alessandro Catalano e Simone Guagnelli COMITATO SCIENTIFICO Giuseppe Dell’Agata, Nicoletta Marcialis, Paolo Nori, Jirˇ´ı Pelan,´ Gian Piero Piretto, Stanislav Savickij COPERTINA, IMPAGINAZIONE E PROGETTO GRAFICO Simone Guagnelli Indirizzo elettronico della rivista: http://www.esamizdat.it e-mail: [email protected] Sede: Via Principe Umberto, 18 – 00185 Roma Sono autorizzate la stampa e la copia purche´ riproducano fedelmente e in modo chiaro la fonte citata. Libri e materiale cartaceo possono essere inviati a Alessandro Catalano, Via Principe Umberto, 18 – 00185 Roma o a Simone Guagnelli, Via Carlo Denina, 22 – 00179 Roma. Articoli e altri contributi elettronici vanno inviati in formato word o LATEX all’indirizzo [email protected] I criteri redazionali sono scaricabili all’indirizzo: www.esamizdat.it/criteri redazionali.htm www.esamizdat.it SECOLO UNIONE SOVIETICA XX IL SAMIZDAT TRA MEMORIAL’ DITORIACLANDESTINAE E UTOPIAIN CECOSLOVACCHIANELLA E SECONDA METÀ DEL A cura di Alessandro Catalano e Simone Guagnelli Paolo Nori, Un intervento variopinto i-vii I NTRODUZIONE 2010-2011 (VIII) Alessandro Catalano, Simone Guagnelli, “La luce dell’est: il - samizdat come costruzione di una comunità parallela” A RCHEOLOGIA DEL SAMIZDAT Samizdat e Valentina Parisi, “Samizdat: problemi di definizione” - Tomáš Glanc, “Il samizdat come medium”, traduzione dal ceco - di Francesca Lazzarin Indice di Annalisa Cosentino, “Forme del samizdat” - Andrej Ju. Ar´ev, “Le preferenze estetiche del samizdat”, - traduzione dal russo di Maria Isola Jirinaˇ Šiklová, “Il samizdat come mezzo di stratificazione so- - ciale e possibilità di sopravvivenza della cultura di una na- zione. -

Political Conflict and Power Sharing in the Origins of Modern Colombia

Political Conflict and Power Sharing in the Origins of Modern Colombia Sebastián Mazzuca and James A. Robinson Colombia has not always been a violent country. In fact, for the first half of the twentieth century, Colombia was one of the most peaceful countries in Latin America, standing out in the region as a highly stable and competitive bipartisan democracy. When faced with the critical test for political stability in that epoch, the Great Depression of 1930, Colombia was the only big country in South America in which military interventions were not even considered. While an armed coup interrupted Argentina’s until then steady path to democracy, and Getulio Vargas installed the first modern dictatorship in Brazil, Colombia cele brated elections as scheduled. Moreover, the ruling party lost the contest, did not make any move to cling to power, and calmly transferred power to the opposition. However, Colombia was not born peaceful. That half-century of peaceful political existence was a major novelty in Colombian history. Colombia’s nine- teenth century was politically chaotic even by Hispanic American standards: the record includes nine national civil wars, dozens of local revolts and mutinies, material destruction equivalent to the loss of several years of economic output, and at least 250,000 deaths due to political violence. How did Colombia make the transition from political chaos to political order? What were the causes of conflict before the turn of the century, and what were the bases of internal peace after it? The emergence of order in Colombia was temporally correlated with a major transformation of political institutions: the introduction of special mechanisms for power sharing between Liberals and Conservatives, Colombia’s two dominant political forces. -

The Evolution of the Party Systems of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic After the Disintegration of Czechoslovakia

DOI : 10.14746/pp.2017.22.4.10 Krzysztof KOŹBIAŁ Jagiellonian University in Crakow The evolution of the party systems of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic after the disintegration of Czechoslovakia. Comparative analysis Abstract: After the breaking the monopoly of the Communist Party’s a formation of two independent systems – the Czech and Slovakian – has began in this still joint country. The specificity of the party scene in the Czech Republic is reflected by the strength of the Communist Party. The specificity in Slovakia is support for extreme parties, especially among the youngest voters. In Slovakia a multi-party system has been established with one dominant party (HZDS, Smer later). In the Czech Republic former two-block system (1996–2013) was undergone fragmentation after the election in 2013. Comparing the party systems of the two countries one should emphasize the roles played by the leaders of the different groups, in Slovakia shows clearly distinguishing features, as both V. Mečiar and R. Fico, in Czech Republic only V. Klaus. Key words: Czech Republic, Slovakia, party system, desintegration of Czechoslovakia he break-up of Czechoslovakia, and the emergence of two independent states: the TCzech Republic and the Slovak Republic, meant the need for the formation of the political systems of the new republics. The party systems constituted a consequential part of the new systems. The development of these political systems was characterized by both similarities and differences, primarily due to all the internal factors. The author’s hypothesis is that firstly, the existence of the Hungarian minority within the framework of the Slovak Republic significantly determined the development of the party system in the country, while the factors of this kind do not occur in the Czech Re- public. -

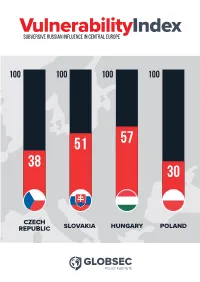

Vulnerabilityindex

VulnerabilitySUBVERSIVE RUSSIAN INFLUENCE IN CENTRAL EUROPE Index 100 100 100 100 51 57 38 30 CZECH REPUBLIC SLOVAKIA HUNGARY POLAND Credits Globsec Policy Institute, Klariská 14, Bratislava, Slovakia www.globsec.org GLOBSEC Policy Institute (formerly the Central European Policy Institute) carries out research, analytical and communication activities related to impact of strategic communication and propaganda aimed at changing the perception and attitudes of the general population in Central European countries. Authors: Daniel Milo, Senior Research Fellow, GLOBSEC Policy Institute Katarína Klingová, Research Fellow, GLOBSEC Policy Institute With contributions from: Kinga Brudzinska (GLOBSEC Policy Institute), Jakub Janda, Veronika Víchová (European Values, Czech Republic), Csaba Molnár, Bulcsu Hunyadi (Political Capital Institute, Hungary), Andriy Korniychuk, Łukasz Wenerski (Institute of Public Affairs, Poland) Layout: Peter Mandík, GLOBSEC This publication and research was supported by the National Endowment for Democracy. © GLOBSEC Policy Institute 2017 The GLOBSEC Policy Institute and the National Endowment for Democracy assume no responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication or their subsequent use. Sole responsibility lies with the authors of this publication. Table of Contents Executive Summary 4 Country Overview 7 Methodology 9 Thematic Overview 10 1. Public Perception 10 2. Political Landscape 15 3. Media 22 4. State Countermeasures 27 5. Civil Society 32 Best Practices 38 Vulnerability Index Executive Summary CZECH REPUBLIC: 38 POLAND: 30 PUBLIC PERCEPTION 36 20 POLITICAL LANDSCAPE 47 28 MEDIA 34 35 STATE COUNTERMEASURES 23 33 CIVIL SOCIETY 40 53 SLOVAKIA: 51 53 HUNGARY: 57 50 31 40 78 78 60 39 80 45 The Visegrad group countries in Central Europe (Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia – V4) are often perceived as a regional bloc of nations sharing similar aspirations, aims and challenges. -

The Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 17, Issue 1 1993 Article 3 A Privatization Test: The Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland Michele Balfour∗ Cameron Crisey ∗ y Copyright c 1993 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj A Privatization Test: The Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland Michele Balfour and Cameron Crise Abstract The nations of the former Communist bloc face a task unparalleled in the annals of world history. By promoting allocation of market resources based on politics and social policy instead of economic efficiencies, the former regimes created economies of inefficiency. Committed eco- nomic reformers face the task of reallocating resources from inefficient producers dependent on government monies to competitive independent market players. This transformation is known as privatization. Privatization is an arduous process, which cannot be accomplished all at once. By shifting assets from uncompetitive players to competitive ones, privatization will impose economic hardship on the public, which will demand the relief it is accustomed to receiving from political leadership. Often, the reformers do not know how to garner public support for privatization. Pos- itive results will emerge only after long-term sacrifice by the people. This article will identify eight requirements for a successful privatization program and discuss the privatization efforts of the former Czechoslovakia, its successor states, and Poland, comparing them and evaluating them against the eight criteria. A PRIVATIZATION TEST: THE CZECH REPUBLIC, SLOVAKIA AND POLAND Michele Balfour Cameron Crise* CONTENTS Introduction ............................................... 85 I. Requirements for Successful Privatization ........... 86 A. Institutional Environment ...................... -

An Analytical Approach Applied to the Slovakian Coal Region †

energies Article Regional Energy Transition: An Analytical Approach Applied to the Slovakian Coal Region † Hana Gerbelová *, Amanda Spisto and Sergio Giaccaria European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), 1755 LE Petten, The Netherlands; [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (S.G.) * Correspondence: [email protected] † This paper is an extended version of our paper published in 15th Conference on Sustainable Development of Energy, Water and Environment Systems (SDEWES), Cologne, Germany, 1–5 September 2020. Abstract: This study presents an analytical framework supporting coal regions in a strategy toward the clean energy transition. The proposed approach uses a combination of value chain analysis and energy sector analysis that enables a comprehensive assessment considering local specificities. Its application to a case study of the Slovakian region Upper Nitra demonstrates practical examples of opportunities and challenges. The value chain analysis evaluates the coal mining industry, from coal extraction to electricity generation, in terms of jobs and business that are at risk by the closure of the coal mines. The complementary energy system analysis focuses on diversification of the energy mix, environmental impacts, and feasibility assessment of alternative energy technologies to the coal combusting sources. The results show a net positive cost benefit for all developed scenarios of replacing the local existing coal power plant. Although the installation of a new geothermal plant is estimated to be the most expensive option from our portfolio of scenarios, it presents the highest CO2 reduction in the electricity generation in Slovakia—34% less compare to the system employing the existing power plant. -

M. Iu. Lermontov

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 409 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Walter N. Vickery M. Iu. Lermontov His Life and Work Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. Walter N. Vickery - 9783954790326 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 02:27:08AM via free access 00056058 SLAVISTICHE BEITRÄGE Herausgegeben von Peter Rehder Beirat: Tilman Berger • Walter Breu • Johanna Renate Döring-Smimov Walter Koschmal ■ Ulrich Schweier • Milos Sedmidubsky • Klaus Steinke BAND 409 V erla g O t t o S a g n er M ü n c h en 2001 Walter N. Vickery - 9783954790326 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 02:27:08AM via free access 00056058 Walter N. Vickery M. Iu. Lermontov: His Life and Work V er la g O t t o S a g n er M ü n c h en 2001 Walter N. Vickery - 9783954790326 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 02:27:08AM via free access PVA 2001. 5804 ISBN 3-87690-813-2 © Peter D. Vickery, Richmond, Maine 2001 Verlag Otto Sagner Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner D-80328 München Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier Bayerisch* Staatsbibliothek Müocfcta Walter N. Vickery - 9783954790326 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 02:27:08AM via free access When my father died in 1995, he left behind the first draft of a manuscript on the great Russian poet and novelist, Mikhail Lermontov.