Diane Simpson Interview Extract.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

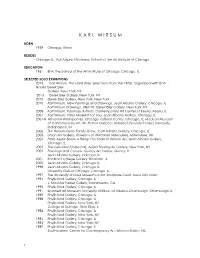

Karl Wirsum B

Karl Wirsum b. 1939 Lives and works in Chicago, IL Education 1961 BFA, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL Solo Exhibitions 2019 Unmixedly at Ease: 50 Years of Drawing, Derek Eller Gallery, NY Karl Wirsum, Corbett vs Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2018 Drawing It On, 1965 to the Present, organized by Dan Nadel and Andreas Melas, Martinos, Athens, Greece 2017 Mr. Whatzit: Selections from the 1980's, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY No Dogs Aloud, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2015 Karl Wirsum, The Hard Way: Selections from the 1970s, Organized with Dan Nadel, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2013 Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Drawings: 1967-70, co-curated by Dan Nadel, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2008 Karl Wirsum: Paintings & Prints, Contemporary Art Center of Peoria, Peoria, IL Winsome Works(some), Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago, IL; traveled to Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, WI; Herron Galleries, Indiana University- Perdue University, Indianapolis, IN 2007 Karl Wirsum: Plays Missed It For You, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2006 The Wirsum-Gunn Family Show, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2005 Union Art Gallery, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI 2004 Hello Again Boom A Rang: Ten Years of Wirsum Art, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2002 Paintings and Cutouts, Quincy Art Center, Quincy, IL Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2001 Rockford College Gallery, Rockford, IL 2000 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 1998 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL University Club of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1997 The University of Iowa Museum of Art, Sculpture Court, Iowa City, IA 1994 Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, IL J. -

Roger Brown (1941 – 1997)

Roger Brown (1941 – 1997) Born, Hamilton, AL Died, Atlanta, GA Education 1970, MFA School of the Art Institute of Chicago 1968, BFA School of the Art Institute of Chicago 1962-1964 attended the American Academy of Art Solo Exhibitions 2015 Roger Brown: Political Paintings, DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY, June 18 – July 31, 2015 Roger Brown: Virtual Still Life, Maccarone Gallery, New York, NY, June 25 – August 7, 2015 2014 Roger Brown: Virtual Still Life, Russell Bowman Art Advisory, September 5 – November 1, 2014 Roger Brown: His American Icons, The Hughes Gallery, Sydney, Australia, March 22 - April 14, 2014 2013 Roger Brown, DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY, January 10 - February 9, 2013 2012 Roger Brown: This Boy’s Own Story, Sullivan Galleries, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, IL, August 24 – November 10, 2012 Dual exhibition, Roger Brown: Major Paintings, Russell Bowman Art Advisory, Chicago, IL and Zolla Lieberman Gallery, Chicago, IL, September 7 - October 27, 2012 Roger Brown: Urban Traumas and Natural Disasters, Springfield Art Museum, Springfield, MO, September 17 – November 13, 2012 2011 Roger Brown: Calif. U.S.A., Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago, IL, June 20 – October 3 roger brown: urban traumas and natural disasters, Springfield Art Museum, Springfield, MO, September 17 - November 13 1 2010 Roger Brown: Calif. U.S.A., curated by Nicholas Lowe, Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago, IL, June 20 – October 3, 2010 2009 Roger Brown: Early Work, Major Paintings and Constructions, 1968-1980, Russell Bowman Art Advisory, Chicago, IL, March 27 – May 16 Roger Brown, Art Works: Chicago A Progressive Corporate Exhibition of Chicago Artists, Metropolitan Capital Bank, Chicago, IL 2008 Roger Brown: The American Landscape, DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY, May 1 – June 13 2007-2009 Roger Brown: Southern Exposure, curated by Sidney Lawrence, The Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art at Auburn University, AL, October 6, 2007 – January 5, 2008. -

Roger Brown, a Leading Painter of the Chicago

Roger Brown, 55, Leading Chicago Imagist Painter, Dies Roberta Smith November 26, 1997 THE NEW YORK TIMES Roger Brown, a leading painter of the Chicago Imagist style, whose radiant, panoramic images were as passionately po- litical as they were rigorously visual, died on Saturday at Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta. He was 55 and had homes and studios in Chicago, New Buffalo, Mich., and Carpen- teria, Calif. The cause was liver failure after a long illness, said Phyllis Kind of the Phyllis Kind Gallery, which has represented Mr. Brown since 1970. In the late 1960’s and early 70’s, Mr. Brown was one of a number of artists whose interests and talents coalesced into one of the defining moments in postwar Chicago art. The inspiration for these artists came from European Surrealism, which was prevalent in the city’s public and private collections; contemporary outsider art, which the Imagists helped promote, and popular culture, recently sanctioned by Pop Artists. In addition to Mr. Brown, these artists included Jim Nutt, Ed Paschke, Phil Hanson, Ray Yoshida, Karl Wirsum, Barbara Rossi and Gladys Nilsson, almost all of whom he met as a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and each of whom braided the city’s disparate cultural strands into a distinctive hybrid of figurative styles. Mr. Brown’s hybrid was a powerful combination of flattened, cartoonish images that featured isometric skyscrapers and tract houses, furrowed fields, undulating hills, pillowy clouds and agitated citizens, the latter usually seen in black silhouette at stark yellow windows where they enacted violent or sexual shadow plays. -

To Download Resume in Pdf Format

G L A D Y S N I L S S O N BORN 1940 Chicago, IL EDUCATION 1962 The School of the Art Institute of Chicago FELLOWSHIPS & AWARDS 2004 William A. Patton Prize for Watercolor, The 179th Annual: An Invitational Exhibition of Contemporary American Art, National Academy Museum, New York, NY 1974 & 89 NEA Fellowship SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Gladys Nilsson: The 1980s, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, NY 2014 Solo Show at Garth Greenan Gallery, New York NY 2013 Hidden Treasures Unveiled: Watercolors Pennsylvania Academy of The Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA 2012 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2011 Hanes Art Gallery, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC 2010 Gladys Nilsson: Works from 1966-2010, Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art, Chicago, IL 2009 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2008 Luise Ross Gallery, New York, NY The Baseball Show, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2007 25 Years of Watercolors, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2006 Rockford College Art Museum, Rockford, IL Tarble Art Center, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, IL 2005 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL University Art Gallery, Saginaw Valley State University, University Center, MI 2004 Tory Folliard Gallery, Milwaukee, WI 2003 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL Adrian College, Adrian, MI (with catalogue) 2002 Watercolors, Quincy Art Center, Quincy, IL Fleisher/Ollman Gallery, Philadelphia, PA 2001 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL Tacoma Art Museum, Tacoma, WA 2000 Rosemont College, Rosemont, PA Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 1998 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL A -

Art Green Biography

Art Green Biography 1941 1978 Born: Frankfort, Indiana Art Green, Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, February 4– Lives and works in Stratford, Ontario March Art Green, Arts Center Gallery, University of Waterloo, Ontario, February 8–March 4 EDUCATION 1961–1965 1979 School of the Art Institute of Chicago Art Green, Gallery Stratford, Ontario, March 16–April 8 Art Green, Bau-Xi Gallery, Toronto, April 28–May 17 Art Green, Phyllis Kind Gallery, New York, May–June TEACHING 1968–1969 1980 Kendall College, Evanston, Illinois Art Green, Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, March 1969–1971 1981–1982 Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax Art Green, Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, December 1981–January 1982 1975–1976 University of British Columbia, Vancouver 1983 Art Green, Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, September– 1977–2006 October University of Waterloo, Ontario Art Green, Bau-Xi Gallery, Toronto, April 21–May 10 1986 SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS Art Green, Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, January– 1968 February Art Green, Art Gallery, Kendall College, Evanston, Illinois, October 1991 Doors of Perception, Cambridge Public Library and 1973 Gallery, Cambridge, Ontario, October 10–November Art Green, Owens Art Gallery, Mt. Alison University, 10 Sackville, New Brunswick, March 31–April 21 Art Green, Burnaby Art Gallery, Burnaby, British 1992 Columbia, October 3–28 Art Green: Conflicts and Resolutions, Gallery Stratford, Ontario, September 11–October 25; McLaren Art 1974 Gallery, Barrie, Ontario, September 17–October 31 Art Green, Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, -

Christina Ramberg CV

CHRISTINA RAMBERG 1946 b. Fort Campbell, KY 1995 d. Chicago, IL Education 1973 MFA, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago 1968 BFA, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago Teaching The School of the Art Institute of Chicago Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago Selected Solo Exhibitions 2019 The Making of Husbands: Christina Ramberg in Dialogue, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany 2014 Glasgow International, 42 Carlton Place, Glasgow 2013 Christina Ramberg, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston 2011 Christina Ramberg: Corset Urns and Other Inventions, 1968 – 1980, David Nolan Gallery, New York 2001 Christina Ramberg Paintings and Drawings, Adam Baumgold Gallery, New York 2000 Christina Ramberg Drawings, Gallery 400 at University of Illinois at Chicago Ben Maltz Gallery at Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles, California Herron Gallery at the Herron School of Art, Indianapolis, Indiana Marsh Gallery at University of Richmond Museums, Richmond, Virginia 1988 Christina Ramberg: A Retrospective 1968-1988, The Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago 1982 Phyllis Kind Gallery, New York 1981 Phyllis Kind Gallery, New York 1977 Phyllis Kind Gallery, New York 1974 Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago Selected Group Exhibitions 2019 How Chicago! Imagists 1960s to 70s, Goldsmiths CCA, London, England A Detached Hand, Magenta Plains, New York Body Object, George Adams Gallery, New York 2018 women are very good at crying and they should be getting paid for it, kaufmann repetto, New York 2017 We Are Here, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Chicago I Was A Wall, And My Breasts Were Like Fortress Towers, Adams and Ollman, Portland Her Eyes Are Like Doves Beside Streams of Water, Adams and Ollman, Portland 2016 Monster Roster: Existentialist Art in Postwar Chicago, Smart Museum of Art, Chicago 2015 America Is Hard to See, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York Surrealism: The Conjured Life, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago Unorthodox, Jewish Museum, New York Order, Essex Street, New York About Face, Kayne Griffin Corcoran, Los Angeles. -

Gladys Nilsson Biography

Gladys Nilsson Biography 1940 1978 Born: Chicago, Illinois Gladys Nilsson, Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago 1979 EDUCATION Gladys Nilsson, Portland Center for the Visual Arts, Oregon, January 18–February 18 1958–1962 Gladys Nilsson, Phyllis Kind Gallery, New York, School of the Art Institute of Chicago February–March 1979–1980 SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS Gladys Nilsson: Survey of Works on Paper, 1967–1979, Fine Arts Gallery, Wake Forest University, Winston- 1966 Salem, North Carolina, September 17–October 17, Gladys Nilsson, Marjorie Dell Gallery, Chicago 1979; Art Gallery, Corpus Christi State University, Texas, January 8–31, 1980; Wustum Museum of Fine 1969 Arts, Racine, Wisconsin, February 17–March 23, 1980 Gladys Nilsson, Clay Street Gallery, San Francisco Art Institute, June 10–28 1981 Gladys Nilsson, Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, January– 1970 February Gladys Nilsson, Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, January– February 1982 Gladys Nilsson, Phyllis Kind Gallery, New York 1971 Gladys Nilsson, Art Gallery, Chico State College, Chico, 1983 California Gladys Nilsson, Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, May–June Gladys Nilsson, Candy Store Gallery, Folsom, California 1984 1973 Gladys Nilsson: Greatest Hits from Chicago, Selected Gladys Nilsson, Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, February Works 1967–1984, Randolph Street Gallery, Chicago, Gladys Nilsson, Whitney Museum of American Art, New May 5–June 23 York, April 12–May 13 1985 1974 Gladys Nilsson, Galerie Bonnier, Geneva, Switzerland, Gladys Nilsson, Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago April 1975 1987 Gladys -

K a R L W I R S

K A R L W I R S U M BORN 1939 Chicago, Illinois RESIDES Chicago, IL Full Adjunct Professor, School of the Art Institute of Chicago EDUCATION 1961 BFA, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 Karl Wirsum, The Hard Way: Selections from the 1970s, Organized with Dan Nadel, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2013 Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Derek Eller Gallery, New York, New York 2010 Karl Wirsum: New Paintings and Drawings, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL Karl Wirsum Drawings: 1967-70, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2008 Karl Wirsum: Paintings & Prints, Contemporary Art Center of Peoria, Peoria, IL 2007 Karl Wirsum: Plays Missed It For You, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2007-8 Winsome Works(some), Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago, IL; Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, WI; Herron Galleries, Indiana University-Perdue University, Indianapolis, IN 2006 The Wirsum-Gunn Family Show, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2005 Union Art Gallery, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI 2004 Hello Again Boom A Rang: Ten Years of Wirsum Art, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2003 The Ganzfeld (Unbound), Adam Baumgold Gallery, New York, NY 2002 Paintings and Cutouts, Quincy Art Center, Quincy, IL Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2001 Rockford College Gallery, Rockford, IL 2000 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 1998 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL University Club of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1997 The University of Iowa Museum of Art, Sculpture Court, Iowa City, Iowa 1994 Phyllis Kind Gallery, -

Gladys Nilsson Cv

GLADYS NILSSON CV Born 1940, Chicago, IL, USA Lives and works in Chicago, IL, USA EDUCATION 1958-1962 The School of the Art Institue of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Unencumbered, Hales London, UK 2017 Gladys Nilsson, The 1980s, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, NY, USA 2014 Gladys Nilsson, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, NY, USA 2013 Gladys Nilsson, New Watercolors, Tory Folliard Gallery, Milwaukee, WI, USA 2012 Gladys Nilsson, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL, USA 2010 Gladys Nilsson, Works from 1966–2010, Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art, Chicago, IL, USA 2009 Gladys Nilsson, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL, USA 2008 Gladys Nilsson, Luise Ross Gallery, New York, NY, USA 2007 Gladys Nilsson, 25 Years of Watercolors, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL, USA 2004 Gladys Nilsson, Tory Folliard Gallery, Milwaukee, WI, USA 2003 Gladys Nilsson, Adrian College, Adrian, MI, USA Gladys Nilsson, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL, USA 2002 Gladys Nilsson, Fleisher/Ollman Gallery, Philadelphia, PA, USA 1998 Gladys Nilsson, A Print Survey, Printworks Gallery, Chicago, IL, USA Gladys Nilsson, John Natsoulas Gallery, Davis, CA, USA London, 7 Bethnal Green Road, E1 6LA. + 44 (0)20 7033 1938 New York, 547 West 20th Street, NY 10011. + 1 646 590 0776 www.halesgallery.com @halesgallery 1997 Gladys Nilsson, Watercolors, Fleisher/Ollman Gallery, Philadelphia, PA, USA Gladys Nilsson, John Natsoulas Gallery, Davis, CA, USA 1996 Gladys Nilsson, Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA, USA 1994 Gladys Nilsson, John Natsoulas Gallery, Davis, -

RICHARD HULL B

RICHARD HULL b. 1955 Oklahoma City, OK Lives and works in Chicago EDUCATION 1979 MFA, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1977 BFA, Kansas City Art Institute, Kansas City, MO 1976 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, ME SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 New Work, Western Exhibitions, Chicago, IL 2016 Richard Hull, Merwin and Wakeley Galleries, Illinois Wesleyan University, Bloomington, IL 2015 Western Exhibitions, Chicago, IL 2014 Metropolitan Capital Bank, organized by Nixon Art Associates. Chicago, IL 2013 Bruno David Gallery, St. Louis 2012 Western Exhibitions, Chicago, IL 2011 Paintings and Drawings, Charlotte & Phillip Hanes Art Gallery, Wake Forest University, NC 2010 Partial Vision, Western Exhibitions, Chicago, IL 2008 Carrie Secrist Gallery, Chicago IL 2006 37 Day Drawing, Carrie Secrist Gallery, Chicago IL Tarble Arts Center, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston Illinois Carrie Secrist Gallery, Chicago IL Saginaw Valley State University, Saginaw Valley, MI 2003 Carrie Secrist Gallery, Chicago, IL Rule Gallery, Denver, CO 2001 Carrie Secrist Gallery, Chicago, IL Rule Gallery, Denver, CO Collaboration with Ken Vandermark, The Arts Club of Chicago, Chicago IL 1999 Carrie Secrist Gallery, Chicago, IL U.U., Brooklyn, NY 1998 Bradley University, Peoria, IL 1997 Gallery A, Inc., Chicago, IL University Club, Chicago, IL 1996 Gallery A, Inc., Chicago, IL 1995 Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, IL 1993 Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, IL Butters Gallery, Portland, OR Rule Modern, Denver, CO 1992 Arthur Roger Gallery, -

Oral History Interview with Phyllis Kind, 2007 March 28-May 11

Oral history interview with Phyllis Kind, 2007 March 28-May 11 Funded by Widgeon Point Charitable Foundation. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Phyllis Kind on March 27, 2008. The interview took place in Kind's home in New York City, and was conducted by James McElhinney for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview JAMES MCELHINNEY: Hello? Testing, testing, testing. [Audio Break.] JAMES MCELHINNEY: I think we're rolling. This is James McElhinney interviewing Phyllis Kind at—your home? Your gallery? PHYLLIS KIND: My home. JAMES MCELHINNEY: Your home, at— PHYLLIS KIND: Would you like to remember the address? JAMES MCELHINNEY: I'm trying to—440 West 22nd Street, in New York— PHYLLIS KIND: That's it. JAMES MCELHINNEY: —on the 28th of March for the Archives of American Arts Smithsonian Institution, disc number one. Well, we appear to be in business as far as the interview goes. So where and—where were you born? You don't have to say when. PHYLLIS KIND: I was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1933, at Beth Israel Hospital. JAMES MCELHINNEY: Hour? Do you know when? PHYLLIS KIND: At 8 a.m. in the morning on the 1st of April which, as you know, is some sort of special day, which I thought was invented for myself, thank you. -

CHRISTINA RAMBERG Born 1946 Fort Campbell, Kentucky Died 1995 Chicago, IL

CHRISTINA RAMBERG Born 1946 Fort Campbell, Kentucky Died 1995 Chicago, IL Education 1968 BFA The School of the Art Institute of Chicago 1973 MFA The School of the Art Institute of Chicago Faculty, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Hyde Park Art Center Solo Exhibitions 2015 Solo presentation of Christina Ramberg at ADAA The Art Show, David Nolan Gallery, New York 2014 Christina Ramberg (in Glasgow International, Festival 2014), Carlton Place, Glasgow 2013 Christina Ramberg, The Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), Boston 2011 Corset Urns and Other Inventions: 1968-1980, David Nolan Gallery, New York 2001 Paintings and Drawings, Adam Baumgold Gallery, New York 2000 Drawings, Gallery 400 at University of Illinois at Chicago Ben Maltz Gallery at Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles Herron Gallery at the Herron School of Art, Indianapolis, IN Marsh Gallery at University of Richmond Museums, Richmond, VA 1988 A Retrospective 1968-1988, The Renaissance Society, Chicago 1982 Phyllis Kind Gallery, New York 1981 Phyllis Kind Gallery, New York 1977 Phyllis Kind Gallery, New York 1974 Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago Group Exhibitions 2019 The Making of Husbands: Christina Ramberg in Dialogue, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin; traveled to BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK, in 2020 How Chicago! Imagists 1960s & 70s, Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, London, UK; De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill on Sea, East Sussex, England 2018 Eye Deal: Abstract Bodies of the Chicago Imagists, Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Madison, WI The Figure and the Chicago Imagists: Selections from the Elmhurst College Art Collection, Elmhurst Art Museum, Elmhurst, IL 3-D Doings: The Imagist Object in Chicago Art, 1964-1980, Tang Museum at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY Outliers and American Vanguard Art, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.