ONYX4054.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beethoven 32 Plus

FREIES MUSIKZENTRUM STUTTGART FMZ Freies Musikzentrum Am Roserplatz Stuttgarter Str. 15 B e e t h o v e n 3 2 p l u s 0711 / 135 30 10 Die Konzertreihe im FMZ Saison 2008/2009 Die 32 Sonaten von Ludwig van Beethoven sind fester Bestandteil der Konzertliteratur. Immer wieder haben große Pianisten diesen Zyklus aufgeführt und auf unzähligen Schallplatten und CDs eingespielt. Bücher und Publikationen beschäftigen sich mit den Werken und den Interpreta- tionen. Und immer wieder hat es den Reiz, des Besonderen, wenn diese Werke wieder neu er- klingen. Als bekannt wurde, dass der österreichische Pianist Till Fellner sich für die nächsten beiden Kon- zertjahre diesen Zyklus als Projekt vorgenommen hatte, begann Andreas G. Winter, Leiter des FMZ und verantwortlich für die Programmgestaltung, als er Till Fellner dafür gewinnen konnte, diesen Zyklus, den Fellner auch in Wien, London, Paris, Tokio und New York spielt, auch im FMZ üeine Konzeption zu der Reihe „32 “zu entwickeln. Um die 32 Klavier- sonaten von Ludwig van Beethoven, deren erste 3 Abende Fellner in dieser Saison (weitere 4 A- bende in der nächsten) spielen wird, konnte Winter weitere namhafte Interpreten gewinnen, die Werke des großen Komponisten der Aufklärung in Zusammenhang mit Kompositionen von Schubert, Schumann und Brahms stellen werden. Paul Lewis wird die Diabelli-Variationen und Schuberts Impromptus D 935, der Geiger Erik Schu- mann mit Olga Scheps Violinsonaten von Beethoven und Brahms, das Trio Wanderer Klaviertrios von Beethoven und Schubert, der Tenor Marcus Ullmann in einem Liederabend neben „die ferne “Lieder von Schumann und Brahms und in einem Recital mit Mikael Samsonov, der frisch üSolocellist des SWR Radiosinfoieorchesters Stuttgart Sonaten von Beethoven und Schubert und Ben Kim, der dem Publikum bereits aus der letzten Saison in bester Erinnerung ist, mit einem Klavierabend Beethoven und Liszt interpretieren. -

Gidon Kremer Oleg Maisenberg

EDITION SCHWETZINGER FESTSPIELE Bereits erschienen | already available: SCHUMANN SCHUBERT BEETHOVEN PROKOFIEV Fritz Wunderlich Hubert Giesen BEETHOVEN � BRAHMS SCHUbeRT LIEDERABEND Claudio Arrau ���� KLAVIERAB END � PIANO R E C ITAL WebeRN FRITZ WUNDERLICH·HUbeRT GIESEN CLAUDIO ARRAU BeeTHOVEN Liederabend 1965 Piano Recital SCHUMANN · SCHUBERT · BeeTHOVEN BeeTHOVEn·BRAHMS 1 CD No.: 93.701 1 CD No.: 93.703 KREISLER Eine große Auswahl von über 800 Klassik-CDs und DVDs finden Sie bei hänsslerCLassIC unter www.haenssler-classic.de, auch mit Hörbeispielen, Download-Möglichkeiten und Gidon Kremer Künstlerinformationen. Gerne können Sie auch unseren Gesamtkatalog anfordern unter der Bestellnummer 955.410. E-Mail-Kontakt: [email protected] Oleg Maisenberg Enjoy a huge selection of more than 800 classical CDs and DVDs from hänsslerCLASSIC at www.haenssler-classic.com, including listening samples, download and artist related information. You may as well order our printed catalogue, order no.: 955.410. E-mail contact: [email protected] DUO RecITAL Die Musikwelt zu Gast 02 bei den Schwetzinger Festspielen Partnerschaft, vorhersehbare Emigration, musikalische Heimaten 03 SERGEI PROKOFIev (1891 – 1953) Als 1952 die ersten Schwetzinger Festspiele statt- Gidon Kremer und Oleg Maisenberg bei den des Brüsseler Concours Reine Elisabeth. Zwei Sonate für Violine und Klavier fanden, konnten sich selbst die Optimisten unter Schwetzinger Festspielen 1977 Jahre später gewann er in Genua den Paganini- Nr. 1 f-Moll op. 80 | Sonata for Violine den Gründern nicht vorstellen, dass damit die Wettbewerb. Dazu ist – was Kremers Repertoire- eutsch eutsch D and Piano No. 1 in 1 F Minor, Op.80 [28:18] Erfolgsgeschichte eines der bedeutendsten deut- Als der aus dem lettischen Riga stammende, Überlegungen, seine Repertoire-Überraschungen D schen Festivals der Nachkriegszeit begann. -

Piano Trios Gidon Kremer Giedrė Dirvanauskaitė Georgijs Osokins

Piano Trios Gidon Kremer Giedrė Dirvanauskaitė Georgijs Osokins Beethoven Chopin A Gidon Kremer, violin Giedrė Dirvanauskaitė, cello Georgijs Osokins, piano 6 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Frédéric Chopin (1770 – 1827) (1810 – 1849) Trio for Violin, Violoncello, and Piano in C major Piano Trio in G minor, op. 8 arr. by Carl Reinecke after the “Triple Concerto”, op. 56 4 I Allegro con fuoco 10:56 1 I Allegro 18:44 5 II Scherzo 6:45 2 II Largo 5:07 6 III Adagio 6:13 3 III Rondo alla Polacca 13:56 7 IV Finale 5:38 8 Musik der Ewigkeit 9 „Für mich ist es eine Entdeckung, ein wahres Juwel der Kammer musik, auch wenn der Klavierpart – Wie soll es bei Chopin anders sein? – das Hauptgewicht trägt“ , sagt Gidon Kremer, überrascht und wiederum nicht von dem Klaviertrio, das im Werkverzeichnis Frédéric Chopins die Opuszahl 8 trägt. Das Tasteninstrument, das schon zu Lebzeiten Beethovens signifikante technische Verbesserungen erfuhr und permanent weiterentwickelt wurde, dominiert Chopins Schaffen klar. Kein Werk aus seiner Feder ist ohne Klavier gedacht, in den meisten Fällen handelt es sich um Solowerke, die singulär und in ihrer Beliebtheit bei Interpreten wie Hörern bis heute ungebrochen sind. „Seine Persönlichkeit ließ keine Zweifel übrig, regte nicht zu Vermutungen an, auch nicht dazu, seine Psyche zu ergründen, in die Tiefen seiner Seele einzudringen. Man unterlag ganz einfach Chopins persönlichem Reiz … Alles an ihm war voller Harmonie, das – so schien es – keines Kommentars bedurfte … und seine Haltung [war] von einer solch aristokratischen Eleganz gezeichnet, dass man ihn unwillkürlich wie einen Fürsten behandelte.“ – Franz Liszts Worte über Chopin fügen sich zum Klang seiner Musik. -

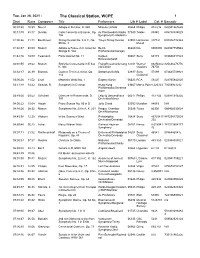

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Tue, Jan 26, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:39 Mozart Adagio in B minor, K. 540 Mitsuko Uchida 00264 Philips 412 616 028941261625 00:13:3945:17 Dvorak Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. du Pre/Swedish Radio 07040 Teldec 85340 685738534029 104 Symphony/Celibidache 01:00:2631:11 Beethoven String Quartet No. 9 in C, Op. Tokyo String Quartet 04508 Harmonia 807424 093046742362 59 No. 3 Mundi 01:32:3708:09 Mozart Adagio & Fugue in C minor for Berlin 06660 DG 0005830 028947759546 Strings K. 546 Philharmonic/Karajan 01:42:1618:09 Telemann Paris Quartet No. 11 Kuijken 04867 Sony 63115 074646311523 Bros/Leonhardt 02:01:5529:22 Mozart Sinfonia Concertante in E flat, Frang/Rysanov/Arcang 12341 Warner 08256462 825646276776 K. 364 elo/Cohen Classics 76776 02:32:1726:39 Brahms Clarinet Trio in A minor, Op. Stoltzman/Ax/Ma 02937 Sony 57499 074645749921 114 Classical 03:00:2611:52 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Evgeny Kissin 06623 RCA 58420 828765842020 03:13:1834:42 Strauss, R. Symphony in D minor Hong Kong 03667 Marco Polo 8.220323 73009923232 Philharmonic/Scherme rhorn 03:49:0009:52 Schubert Overture to Rosamunde, D. Leipzig Gewandhaus 00217 Philips 412 432 028941243225 797 Orchestra/Masur 04:00:2215:04 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 50 in D Julia Cload 02053 Meridian 84083 N/A 04:16:2628:32 Mozart Symphony No. 29 in A, K. 201 Prague Chamber 05596 Telarc 80300 089408030024 Orch/Mackerras 04:45:58 12:20 Webern In the Summer Wind Philadelphia 10424 Sony 88725417 887254172024 Orchestra/Ormandy 202 04:59:4806:23 Lehar Merry Widow Waltz Richard Hayman 08261 Naxos 8.578041- 747313804177 Symphony 42 05:07:11 21:52 Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Entremont/Philadelphia 04207 Sony 46541 07464465412 Paganini, Op. -

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club Since you’re reading this booklet, you’re obviously someone who likes to explore music more widely than the mainstream offerings of most other labels allow. Toccata Classics was set up explicitly to release recordings of music – from the Renaissance to the present day – that the microphones have been ignoring. How often have you heard a piece of music you didn’t know and wondered why it hadn’t been recorded before? Well, Toccata Classics aims to bring this kind of neglected treasure to the public waiting for the chance to hear it – from the major musical centres and from less-well-known cultures in northern and eastern Europe, from all the Americas, and from further afield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, Toccata Classics is exploring it. To link label and listener directly we run the Toccata Discovery Club, which brings its members substantial discounts on all Toccata Classics recordings, whether CDs or downloads, and also on the range of pioneering books on music published by its sister company, Toccata Press. A modest annual membership fee brings you, free on joining, two CDs, a Toccata Press book or a number of album downloads (so you are saving from the start) and opens up the entire Toccata Classics catalogue to you, both new recordings and existing releases as CDs or downloads, as you prefer. Frequent special offers bring further discounts. If you are interested in joining, please visit the Toccata Classics website at www.toccataclassics.com and click on the ‘Discovery Club’ tab for more details. -

19 September 2020

19 September 2020 12:01 AM Johann Strauss II (1825-1899) Spanischer Marsch Op 433 ORF Radio Symphony Orchestra, Peter Guth (conductor) ATORF 12:06 AM Jose Marin (c.1618-1699) No piense Menguilla ya Montserrat Figueras (soprano), Rolf Lislevand (baroque guitar), Pedro Estevan (percussion), Arianna Savall (harp) ATORF 12:12 AM Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) Sonata da Chiesa in B flat major, Op 1 no 5 London Baroque DEWDR 12:19 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Symphony no 4 in D major, K.19 BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Osmo Vanska (conductor) GBBBC 12:32 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) From 24 Preludes for piano, Op 28: Nos. 4-11, 19 and 17 Sviatoslav Richter (piano) PLPR 12:48 AM Henryk Wieniawski (1835-1880) Violin Concerto no 2 in D minor, Op 22 Mariusz Patyra (violin), Polish Radio Orchestra, Wojciech Rajski (conductor) PLPR 01:12 AM Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) 4 Songs for women's voices, 2 horns and harp, Op 17 Danish National Radio Choir, Leif Lind (horn), Per McClelland Jacobsen (horn), Catriona Yeats (harp), Stefan Parkman (conductor) DKDR 01:27 AM Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Suite in E major BWV.1006a Konrad Junghanel (lute) DEWDR 01:48 AM Franz Schubert (1797-1828), Friedrich Schiller (author) Sehnsucht ('Longing') (D.636) - 2nd setting Christoph Pregardien (tenor), Andreas Staier (pianoforte) DEWDR 01:52 AM Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Concerto for 2 trumpets and orchestra in C major, RV.537 Anton Grcar (trumpet), Stanko Arnold (trumpet), RTV Slovenia Symphony Orchestra, Marko Munih (conductor) SIRTVS 02:01 AM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Piano Concerto no 1 in C major, Op 15 Martin Stadtfeld (piano), NDR Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, Andrew Manze (conductor) DENDR 02:35 AM George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) Will the sun forget to streak, from 'Solomon, HWV.67', arr. -

Gold Medal 2018

Thursday 10 May 7pm, Barbican Hall Gold Medal 2018 Finalists Ljubica Stojanovic Dan-Iulian Drut¸ac Joon Yoon Guildhall Symphony Orchestra James Judd conductor Guildhall School of Music & Drama Barbican Founded in 1880 by the Gold Medal 2018 City of London Corporation Please try to restrain from coughing until the normal breaks in the performance. Chairman of the Board of Governors Thursday 10 May 2018 If you have a mobile phone or digital watch, Deputy John Bennett 7pm, Barbican Hall please ensure that it is turned off during the Principal performance. The Gold Medal, the Guildhall School’s premier Lynne Williams In accordance with requirements of the award for musicians, was founded and endowed Vice–Principal and Director of Music licensing authority, sitting or standing in in 1915 by Sir H. Dixon Kimber Bt MA Jonathan Vaughan any gangway is not permitted. No cameras, tape recorders, other types of Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk Finalists recording apparatus may be brought into the auditorium. It is illegal to record any Ljubica Stojanovic piano performance unless prior arrangements Dan-Iulian Drut¸ac violin have been made with the Managing Director Joon Yoon piano and the concert promoter concerned. No eating or drinking is allowed in the The Jury auditorium. Smoking is not permitted Donagh Collins anywhere on the Barbican premises. Kathryn Enticott Paul Hughes Barbican Centre James Judd Silk St, London EC2Y 8DS Jonathan Vaughan (Chair) Administration: 020 7638 4141 Box Office Telephone Bookings: Guildhall Symphony Orchestra 020 7638 8891 (9am-8pm daily: booking fee) James Judd conductor barbican.org.uk The Guildhall School is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london The Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation Gold Medal winners since 1915 Gold Medal 2018 Singers 1979 Patricia Rozario 1947 Mary O White Ljubica Stojanovic piano 1915 Lilian Stiles-Allen 1981 Susan Bickley 1948 Jeremy White Prokofiev Piano Concerto No. -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings. -

Solzh 19-20 Short

IGNAT SOLZHENITSYN 2019-20 SHORT BIO {206 WORDS} IGNAT SOLZHENITSYN Recognized as one of today's most gifted artists, and enjoying an active career as both conductor and pianist, Ignat Solzhenitsyn's lyrical and poignant interpretations have won him critical acclaim throughout the world. Principal Guest Conductor of the Moscow Symphony Orchestra and Conductor Laureate of the Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia, Ignat Solzhenitsyn has recently led the symphonies of Baltimore, Cincinnati, Dallas, Indianapolis, Milwaukee, Seattle, and Toronto, the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie, the Czech National Symphony, as well as the Mariinsky Orchestra and the St. Petersburg Philharmonic. He has partnered with such world-renowned soloists as Richard Goode, Gary Graffman, Gidon Kremer, Anne-Sophie Mutter, Garrick Ohlsson, Mstislav Rostropovich, and Mitsuko Uchida. His extensive touring schedule in the United States and Europe has included concerto performances with numerous major orchestras, including those of Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Seattle, Baltimore, Montreal, Toronto, London, Paris, Israel, and Sydney, and collaborations with such distinguished conductors as Herbert Blomstedt, James Conlon, Charles Dutoit, Valery Gergiev, André Previn, Gerard Schwarz, Wolfgang Sawallisch, Yuri Temirkanov and David Zinman. A winner of the Avery Fisher Career Grant, Ignat Solzhenitsyn serves on the faculty of the Curtis Institute of Music. He has been featured on many radio and television specials, including CBS Sunday Morning and ABC’s Nightline. CURRENT AS OF: 18 NOVEMBER 2019 PLEASE DESTROY ANY PREVIOUS BIOGRAPHICAL MATERIALS. PLEASE MAKE NO CHANGES, EDITS, OR CUTS OF ANY KIND WITHOUT SPECIFIC PERMISSION.. -

Mark-Anthony Turnage Mambo, Blues and Tarantella Riffs and Refrains | Texan Tenebrae on Opened Ground | Lullaby for Hans

Mark-anthony turnage MaMbo, blues aND TaraNTella riffs aND refraiNs | TexaN TeNebrae oN opeNeD GrouND | lullaby for HaNs vladiMir jurowski, Marin alsop and Markus stenZ conductors Christian tetZlaFF violin MiChael Collins clarinet lawrenCe power viola london philharMoniC orChestra LPO-0066 Turnage booklet.indd 1 7/26/2012 11:35:49 AM Mark-anthony turnage advocate. He continued his studies at the senior College with Knussen and Knussen’s own teacher John Lambert, and at the Tanglewood summer school in New England with Gunther Schuller. Through Tanglewood, he also came into contact with Hans Werner Henze, who kick-started Turnage’s international career by commissioning an opera for the 1988 Munich Biennale festival, an adaptation of Steven Berkoff’s play Greek. AL Turnage’s subsequent career has been defined largely by collaborations, both with enaP Ar / improvising jazz performers and in a series of d ar residencies, which have allowed him to develop tw pieces under the workshop conditions he Ga prefers. These have included associations with Philip the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, © leading to several high-profile premières under Simon Rattle; with English National Opera, Mark-Anthony Turnage is a composer widely culminating in 2000 in his second full-length admired for his distinctive blending of jazz and opera, The Silver Tassie; with the BBC Symphony contemporary classical traditions, high energy Orchestra in London; and with the Chicago and elegiac lyricism, hard and soft edges. Born Symphony Orchestra. He was the London in Essex, he began inventing music to enliven Philharmonic Orchestra’s Composer in Focus his childhood piano practice. -

Download Booklet

557921bk USA 14/3/07 10:08 am Page 5 Ashley Wass The young British pianist Ashley Wass is recognised as one of the rising stars of his generation. Only the second British pianist in twenty years to reach the finals of the Leeds Piano Competition (in 2000), he was the first British pianist ever to win the top prize at the World Piano Competition in 1997. He appeared in the Rising Stars series at BRIDGE the 2001 Ravinia Festival and his promise has been further acknowledged by the BBC, who selected him to be a New Generations Artist over two seasons. Ashley Wass studied at Chethams Music School and won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music to study with Christopher Elton and Hamish Milne. In 2002 he was made an Associate of the Royal Academy. He has spent three summers as a participant at the Marlboro Music Festival, Piano Music playing chamber music with musicians such as Mitsuko Uchida, Richard Goode and members of the Guarneri Quartet and Beaux Arts Trio. He has given recitals at most of the major British concert halls, including the Wigmore Hall, Queen Elizabeth Hall, Symphony Hall, Purcell Room, Bridgewater Hall and St David’s Hall, with Piano Sonata appearances at the City of London Festival, Bath Festival, Brighton Festival, Cheltenham Festival, Belfast Waterfront Hall, Symphony Hall in Birmingham, the Wallace Collection, LSO St Luke’s, St George’s in Bristol, Three Sketches • Pensées fugitives Chicago’s Cultural Centre and Sheffield ‘Music in the Round’. His concerto performances have included Beethoven and Brahms with the Philharmonia, Mendelssohn with the Orchestre National de Lille and Mozart with the Vienna Chamber Orchestra at the Vienna Konzerthaus and the Brucknerhaus in Linz. -

Pablo Ferrandez-Castro, Cello

Pablo Ferrández-Castro, Cello Awarded the coveted ICMA 2016 “Young Artist of the Year”, and prizewinner at the XV International Tchaikovsky Competition, Pablo Ferrández is praised by his authenticity and hailed by the critics as “one of the top cellists” (Rémy Louis, Diapason Magazine). He has appeared as a soloist with the Mariinsky Orchestra, Vienna Symphony Orchestra, St. Petersburg Philharmonic, Stuttgart Philharmonic, Kremerata Baltica, Helsinki Philharmonic, Tapiola Sinfonietta, Spanish National Orchestra, RTVE Orchestra, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, and collaborated with such artists as Zubin Mehta, Valery Gergiev, Yuri Temirkanov, Adam Fischer, Heinrich Schiff, Dennis Russell Davies, John Storgårds, Gidon Kremer, Ivry Gitlis and Anne-Sophie Mutter. Highlights of the 2016/17 season include his debut with BBC Philharmonic under Juanjo Mena, his debut at the Berliner Philharmonie with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, his collaboration with Christoph Eschenbach playing Schumann’s cello concerto with the HR- Sinfonieorchester and with the Spanish National Symphony, the return to Maggio Musicale Fiorentino under Zubin Mehta, recitals at the Mariinsky Theater and Schloss-Elmau, a European tour with Kremerata Baltica, appearances at the Verbier Festival, Jerusalem International Chamber Music Festival, Intonations Festival and Trans-Siberian Arts Festival, his debuts with Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale RAI, Barcelona Symphony Orchestra, Munich Symphony, Estonian National Symphony, Taipei Symphony Orchestra, Queensland Symphony Orchestra, and the performance of Brahms' double concerto with Anne-Sophie Mutter and the London Philharmonic Orchestra. Mr. Ferrández plays the Stradivarius “Lord Aylesford” (1696) thanks to the Nippon Music Foundation. .