Kamwe (Higgi) Origin(S), Migration(S) and Settlement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Iom Shelter Needs Assessment in Return Areas: Adamawa State

International Organization for Migration IOM SHELTER NEEDS ASSESSMENT IN RETURN AREAS: ADAMAWA STATE October 2017 Shelter Needs Assessment Report IOM Shelter Needs Assessment in Return Areas: Adamawa State Table of Content BACKGROUND ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 OBJECTIVE ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 COVERAGE ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 METHODOLOGY ……………………………………………………………………………….. 5 FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS Demographic Profile …………………………………………………………………………. 6 Housing, Land and Property ………………………………………………………………… 13 Housing Condition ……………………………………………………………………………18 Damage Assessment …………………………………………………………………………22 Access to Other Services …………………………………………………………………….29 RECOMMENDATIONS …………………………………………………………………………. 35 Page 1 IOM Shelter Needs Assessment in Return Areas: Adamawa State BACKGROUND In North-Eastern Nigeria, attacks and counter attacks have resulted in prolonged insecurity and endemic violations of human rights, triggering waves of forced displacement. Almost two million people remain displaced in Nigeria, and displacement continues to be a significant factor in 2017. Since late 2016, IOM and other humanitarian partners have been able to scale up on its activities. However, despite the will and hope of the humanitarian community and the Government of Nigeria and the dedication of teams and humanitarian partners in supporting them, humanitarian needs have drastically increased and the humanitarian response needs to keep scaling up to reach all the affected population in need. While the current humanitarian -

Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit?

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1| Jan-Feb-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.003 Research Article Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit? Venantius Kum NGWOH Ph.D* Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Buea, Cameroon Abstract: The national symbols of Cameroon like flag, anthem, coat of arms and seal do not Article History in any way reveal her cultural background because of the political inclination of these signs. Received: 14.01.2020 In global sporting events and gatherings like World Cup and international conferences Accepted: 28.12.2020 respectively, participants who appear in traditional costume usually easily reveal their Published: 17.02.2020 nationalities. The Ghanaian Kente, Kenyan Kitenge, Nigerian Yoruba outfit, Moroccan Journal homepage: Djellaba or Indian Dhoti serve as national cultural insignia of their respective countries. The https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs reason why Cameroon is referred in tourist circles as a cultural mosaic is that she harbours numerous strands of culture including indigenous, Gaullist or Francophone and Anglo- Quick Response Code Saxon or Anglophone. Although aspects of indigenous culture, which have been grouped into four spheres, namely Fang-Beti, Grassfields, Sawa and Sudano-Sahelian, are dotted all over the country in multiple ways, Cameroon cannot still boast of a national culture emblem. The purpose of this article is to define the major components of a Cameroonian national culture and further identify which of them can be used as an acceptable domestic cultural device. -

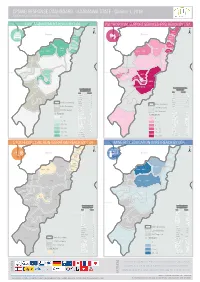

CPSWG RESPONSE DASHBOARD - ADAMAWA STATE - Quarter 1, 2019 Child Protection Sub Working Group, Nigeria

CPSWG RESPONSE DASHBOARD - ADAMAWA STATE - Quarter 1, 2019 Child Protection Sub Working Group, Nigeria YobeCASE MANAGEMENT REACH BY LGA PSYCHOSOCIALYobe SUPPORT SERVICES (PSS) REACH BY LGA 78% 14% Madagali ± Madagali ± Borno Borno Michika Michika 86% 10% 82% 16% Mubi North Mubi North Hong 100% Mubi South 5% Hong Gombi 100% 100% Gombi 10% 27% Mubi South Shelleng Shelleng Guyuk Song 0% Guyuk Song 0% 0% Maiha 0% Maiha Chad Chad Lamurde 0% Lamurde 0% Nigeria Girei Nigeria Girei 36% 81% 11% 96% Numan 0% Numan 0% Yola North Demsa 100% Demsa 26% Yola North 100% 0% Adamawa Fufore Yola South 0% Yola South 100% Fufore Mayo-Belwa Mayo-Belwa Adamawa Local Government Area Local Government (LGA) Target Area (LGA) Target LGA TARGET LGA TARGET Demsa 1,170 DEMSA 78 Fufore 370 Jada FUFORE 41 Jada Ganye 0 GANYE 0 Girei 933 GIREI 16 Gombi 4,085 State Boundary GOMBI 33 State Boundary Guyuk 0 GUYUK 0 LGA Boundary Hong 16,941 HONG 6 Ganye Ganye LGA Boundary Jada 0 JADA 0 Not Targeted Lamurde 839 LAMURDE 6 Not Targeted Madagali 6,321 MADAGALI 119 % Reach Maiha 2,800 MAIHA 12 % REACH Mayo-Belwa 0 0 MAYO - BELWA 0 0 Michika 27,946 Toungo 0% MICHIKA 232 Toungo 0% 1 - 36 Mubi North 11,576 MUBI NORTH 154 1 - 5 Mubi South 11,821 MUBI SOUTH 139 37 - 78 Numan 2,250 NUMAN 14 6 - 11 Shelleng 0 SHELLENG 0 79 - 82 12 - 16 Song 1,437 SONG 21 Teungo 25 83 - 86 TOUNGO 6 17 - 27 Yola North 1,189 YOLA NORTH 14 Yola South 2,824 87 - 100 YOLA SOUTH 47 28 - 100 SOCIO-ECONOMICYobe REINTEGRATION REACH BY LGA MINEYobe RISK EDUCATION (MRE) REACH BY LGA Madagali Madagali R 0% I 0% ± -

17 the Impact of Boko Haram Insurgency on Livestock Production

The Impact of Boko Haram Insurgency on Livestock Production in Mubi Region of Adamawa State, Nigeria. Augustine, C1., Daniel, J.D.2, Abdulrahman, B.S.1 Lubele, M.I.3, Katsala,. J.G.4 and Ardo, M.U.4 1. Department of Animal Production, Adamawa State University, Mubi. 2. Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Adamawa State University, Mubi. 3. Department of History, Adamawa State University, Mubi. 4. Department of Agricultural Education, College of Education, Hong. Abstract: This study was conducted to examine the impact of Boko Haram insurgence on livestock production in Mubi region of Adamawa State, Nigeria. Four local government areas (Mubi north, Mubi south, Madagali and Michika) were purposely selected for this study. Thirty (30) livestock farmers were randomly selected from each of the local government area making a total of one hundred and twenty (120) respondents. One hundred and twenty (120) structured questionnaires were administered to gather information from the farmers through an interview schedule. Majority of the livestock farmers in Mubi south (56.67%) Mubi north (63.33%), Madagali (53.33%) and Michika (80%) were males. Most of the respondents had secondary school certificates (40 to 50%) and Diploma certificates (23.33 to 36.70%). Greater proportion of the livestock farmers had family size of 5 to 10 people per family. Family labour accounted the highest (43.33 to 60%) types of labour used in managing the animals. Sizable population (53.33 to 63.33%) of the livestock farmers kept domestic animals as source of income. Livestock populations were observed to have been drastically reduced as a result of Boko Haram attacks. -

LGA Demsa Fufore Ganye Girei Gombi Guyukk Hong Jada Lamurde

LGA Demsa Fufore Ganye Girei Gombi Guyukk Hong Jada Lamurde Madagali Maiha Mayo Belwa Michika Mubi North Mubi South Numan Toungo Shellenge Song Yola North Yola South PVC PICKUP ADDRESS Along Gombe Road, Demsa Town, Demsa Local Govt. Area Gurin Road, Adjacent Local Govt. Guest House, Fufore Local Govt. Area Along Federal Government College, Ganye Road, Ganye Lga Adjacent Local Govt. Guest Road, Girei Local Govt. Area Sangere Gombi, Aong Yola Road, Gombi L.G.A Palamale Nepa Ward Guyuk Town, Guyuk Local Govt. Area Opposite Cottage Hospital Shangui Ward, Hong Local Govt. Area Old Secretariat, Jada Along Ganye Road, Jada Lafiya Lamurde Road, Lamurde Local Govt. Area Palace Road, Gulak, Near Gulak Police Station, Madagali Lga Behind Local Govt. Secretariat, Mayonguli Ward, Maiha Jalingo Road Near Maternity Mayo Belwa Lga Michika Bye-Pass Zaibadari Ward Michika Lga Inside Local Govt. Secretariat, Mubi North Lumore Street, Opposite District Head's Palace, Gela, Mubi South Councilors Quarters, Off Jalingo Road, Numan Lga Barade Road, Oppoiste Sss Office, Toungo Old Local Govt Secretariat Street, Shelleng Town, Shelleng Lga Opp. Cattage Hospital Yola Road, Song Local Govt. Area No. 7 Demsawo Street, Demsawo Ward, Yola North Lga Yola Bye-Pass Fufore Road Opp. Aliyu Mustapha College, Bako Ward, Yola Town, Yola South Lga Yola Bye-Pass Fufore Road Opp. Aliyu Mustapha College, Bako Ward, Yola Town, Yola South Lga. -

•Chadic Classification Master

Paul Newman 2013 ò ê ž ŋ The Chadic Language Family: ɮ Classification and Name Index ɓ ō ƙ Electronic Publication © Paul Newman This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License CC BY-NC Mega-Chad Research Network / Réseau Méga-Tchad http://lah.soas.ac.uk/projects/megachad/misc.html http://lah.soas.ac.uk/projects/megachad/divers.html The Chadic Language Family: Classification and Name Index Paul Newman I. CHADIC LANGUAGE CLASSIFICATION Chadic, which is a constituent member of the Afroasiatic phylum, is a family of approximately 170 languages spoken in Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, and Niger. The classification presented here is based on the one published some twenty-five years ago in my Nominal and Verbal Plurality in Chadic, pp. 1–5 (Dordrecht: Foris Publications, 1990). This current paper contains corrections and updates reflecting the considerable amount of empirical research on Chadic languages done since that time. The structure of the classification is as follows. Within Chadic the first division is into four coordinate branches, indicated by Roman numerals: I. West Chadic Branch (W-C); II. Biu-Mandara Branch (B-M), also commonly referred to as Central Chadic; III. East Chadic Branch (E-C); and IV. Masa Branch (M-S). Below the branches are unnamed sub-branches, indicated by capital letters: A, B, C. At the next level are named groups, indicated by Arabic numerals: 1, 2.... With some, but not all, groups, subgroups are distinguished, these being indicated by lower case letters: a, b…. Thus Miya, for example, is classified as I.B.2.a, which is to say that it belongs to West Chadic (I), to the B sub-branch of West Chadic, to the Warji group (2), and to the (a) subgroup within that group, which consists of Warji, Diri, etc., whereas Daba, for example, is classified as II.A.7, that is, it belongs to Biu-Mandara (II), to the A sub-branch of Biu-Mandara, and within Biu-Mandara to the Daba group (7). -

Impact of Boko Haram Insurgency on Poultry Production in Mubi Region of Adamawa State, Nigeria

Nigerian J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 21 (3): 145-150 Impact of Boko Haram insurgency on poultry production in Mubi region of Adamawa State, Nigeria Augustine, C1., Daniel, J.D2., Abdulrahman, B.S1 Mojaba, D.I1., Lubele, M.I3., Yusuf, J4 and Katsala, G.J4. 1Department of Animal Production, Adamawa State University, Mubi 2Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Adamawa State University, Mubi 3 Department of History, Adamawa State University, Mubi 4 Department of Agricultural Education, Adamawa State College of Education, Hong. Target audience: Government, Poultry producers, Non-Governmental organisations Abstract This study was conducted to assess the impact of Boko Haram insurgency on poultry production in Mubi region of Adamawa State, Nigeria. Four local government areas namely: Mubi South, Mubi North, Madagali and Michika were purposely selected. Thirty (30) poultry farmers were randomly selected from each of the local government making a total of one hundred and twenty (120) respondents. One hundred and twenty (120) structured questionnaires were used to collect data through scheduled interview. The outcome of this study revealed that majority of the poultry farmers in Mubi South (56.67%), Madagali (53.33%) and Michika (60%) were males. Some proportion of the poultry farmers (26.67 to 36.67%) and (13.33 to 26.67%) had attained secondary and tertiary education (Colleges and Polytechnics) education respectively. Sizable proportion of the poultry farmers in Mubi South (63.33%), Mubi North (53.33%), Madagali (60%) and Michika (60%) kept poultry as source of income. Significant economic losses as a result of Boko Haram activities were recorded with greater losses recorded from layer chicken farms in Mubi South where the sum of N785,000 was lost and N895,000 in Mubi North respectively. -

Adamawa - Health Sector Reporting Partners (April - June, 2020)

Nigeria: Adamawa - Health Sector Reporting Partners (April - June, 2020) Number of Local Reporting PARTNERS PER TYPE Government Area Partners OF ORGANIZATIONS BREAKDOWN OF PEOPLE REACHED PER CATEGORY NGOs/UN People Reached PiN/Target IDP Returnee Host Agencies Community 21 Partners14 including 230,996 LGAs with ongoing International NGOs and activities 95,764 13,922 1,268 80,573 UN Agencies 11/3 212,433 DEMSA (4 Partners) MICHIKA (6 Partners) FSACI, IOM, JHF, WHO GZDI, IRC, JHF, PLAN, WHO, ZSF MADAGALI REACHED: 6,070 REACHED: 6,578 FUFORE (4 Partners) MUBI NORTH (7 Partners) MICHIKA GDZI, IOM, JHF, LESGO, PLAN, IOM, JHF, UNICEF, WHO SWOGE, WHO REACHED: 17,309 REACHED: 6,924 MUBI NORTH GANYE (2 Partners) MUBI SOUTH (6 Partners) HONG JHF GDZI, IOM, JHF, LESGO, RHHF, ZSF GOMBI MUBI SOUTH REACHED: - REACHED: 4,090 GIREI (4 Partners) NUMAN (1 Partner) SHELLENG JHF AGUF, IOM, JHF, WHO MAIHA REACHED: 22,348 REACHED: - SONG GUYUK GOMBI (3 Partners) SHELLENG (1 Partner) JHF GDZI, JHF, WHO LAMURDE REACHED: 220 REACHED: - GIREI GUYUK (2 Partners) SONG (2 Partners) NUMAN AGUF, JHF JHF DEMSA REACHED: - REACHED: 7,355 YOLA SOUTH YOLA NORTH HONG (3 Partners) TOUNGO (1 Partner) GDZI, JHF, WHO JHF MAYO FUFORE REACHED: 423 REACHED: - BELWA JADA (1 Partner) YOLA NORTH (4 Partners) HARAF, IOM, JHF, UNICEF JHF JADA REACHED: - REACHED: 1,224 LAMURDE (1 Partner) YOLA SOUTH (4 Partners) GANYE JHF IOM, JHF, SWOGE, UNICEF Number of Organizations REACHED: - REACHED: 7,355 (3 Partners) MADAGALI 1 7 JHF, PLAN, WHO TOUNGO REACHED: 4,537 MAIHA (2 Partners) JHF, WHO -

A Missionary Handbook on African Traditional Religion

African Traditional Religion A Missionary Handbook on PREFACE African Traditional Religion One of the important areas of study for a missionary or evangelist is to understand the beliefs that people already have before and during the time Lois K Fuller the missionary presents the gospel to them. These beliefs will shape how they understand the message and the problems they have if they want to respond. There are many books on African Traditional Religion. In Nigeria, most 2nd edition, 2001 of them concentrate on the religions of the tribes of the southern part of the This book was first published by NEMI and Africa Christian Textbooks country. This book tries to talk about traditional religion more generally, (ACTS), PMB 2020, Bukuru 930008, Plateau State, Nigeria. Reissued in this format with the permission of the author and publisher by exploring some of the religious ideas found in ethnic groups that do not Tamarisk Publications, 2014. have much of the gospel yet. Most textbooks on Traditional Religion web: www.opaltrust.org describe the religion without relating it to the teachings of the Bible. email: [email protected] However a missionary needs to know how to relate the Bible’s teaching to traditional beliefs. Lois K. Fuller has taught in schools of mission and theological colleges across This book is also about methods we can use to interest followers of ATR many denominations in Nigeria. She served for some years as Dean of Nigeria in the gospel and teach and disciple them so that they will understand the Evangelical Missionary Institute (NEMI). -

An Atlas of Nigerian Languages

AN ATLAS OF NIGERIAN LANGUAGES 3rd. Edition Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road, Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/Answerphone 00-44-(0)1223-560687 Mobile 00-44-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm Skype 2.0 identity: roger blench i Introduction The present electronic is a fully revised and amended edition of ‘An Index of Nigerian Languages’ by David Crozier and Roger Blench (1992), which replaced Keir Hansford, John Bendor-Samuel and Ron Stanford (1976), a pioneering attempt to synthesize what was known at the time about the languages of Nigeria and their classification. Definition of a Language The preparation of a listing of Nigerian languages inevitably begs the question of the definition of a language. The terms 'language' and 'dialect' have rather different meanings in informal speech from the more rigorous definitions that must be attempted by linguists. Dialect, in particular, is a somewhat pejorative term suggesting it is merely a local variant of a 'central' language. In linguistic terms, however, dialect is merely a regional, social or occupational variant of another speech-form. There is no presupposition about its importance or otherwise. Because of these problems, the more neutral term 'lect' is coming into increasing use to describe any type of distinctive speech-form. However, the Index inevitably must have head entries and this involves selecting some terms from the thousands of names recorded and using them to cover a particular linguistic nucleus. In general, the choice of a particular lect name as a head-entry should ideally be made solely on linguistic grounds. -

Fulɓe, Fulani and Fulfulde in Nigeria

FEDERAL DEPARTMENT OF LIVESTOCK & PEST CONTROL SERVICES NIGERIAN NATIONAL LIVESTOCK RESOURCE SURVEY FULƁE, FULANI AND FULFULDE IN NIGERIA: DISTRIBUTION AND IDENTITY WORKING PAPER SERIES. No. 23 [CIRCULATION VERSION] All correspondence to; Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm RESOURCE INVENTORY & MANAGEMENT LIMITED [Original Version, August, 1990] [Revised Version, November, 1994] Nigerian National Livestock Resource Survey: Working Paper 23. R.M. Blench. Circulation Version. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................................ 1 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................... 2 2. THE HISTORY OF THE FULƁE IN NIGERIA..................................................................................... 2 3. FULƁE AND HAUSA: LINGUISTIC, CULTURAL AND ETHNIC IDENTITY ............................... 4 4. FULFULDE AS A VEHICULAR LANGUAGE...................................................................................... 4 5. NON-PASTORAL COMMUNITIES USING FULFULDE.................................................................... 5 6. FUTURE PROSPECTS FOR FULFULDE IN NIGERIA .....................................................................