Fulɓe, Fulani and Fulfulde in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit?

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1| Jan-Feb-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.003 Research Article Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit? Venantius Kum NGWOH Ph.D* Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Buea, Cameroon Abstract: The national symbols of Cameroon like flag, anthem, coat of arms and seal do not Article History in any way reveal her cultural background because of the political inclination of these signs. Received: 14.01.2020 In global sporting events and gatherings like World Cup and international conferences Accepted: 28.12.2020 respectively, participants who appear in traditional costume usually easily reveal their Published: 17.02.2020 nationalities. The Ghanaian Kente, Kenyan Kitenge, Nigerian Yoruba outfit, Moroccan Journal homepage: Djellaba or Indian Dhoti serve as national cultural insignia of their respective countries. The https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs reason why Cameroon is referred in tourist circles as a cultural mosaic is that she harbours numerous strands of culture including indigenous, Gaullist or Francophone and Anglo- Quick Response Code Saxon or Anglophone. Although aspects of indigenous culture, which have been grouped into four spheres, namely Fang-Beti, Grassfields, Sawa and Sudano-Sahelian, are dotted all over the country in multiple ways, Cameroon cannot still boast of a national culture emblem. The purpose of this article is to define the major components of a Cameroonian national culture and further identify which of them can be used as an acceptable domestic cultural device. -

A Missionary Handbook on African Traditional Religion

African Traditional Religion A Missionary Handbook on PREFACE African Traditional Religion One of the important areas of study for a missionary or evangelist is to understand the beliefs that people already have before and during the time Lois K Fuller the missionary presents the gospel to them. These beliefs will shape how they understand the message and the problems they have if they want to respond. There are many books on African Traditional Religion. In Nigeria, most 2nd edition, 2001 of them concentrate on the religions of the tribes of the southern part of the This book was first published by NEMI and Africa Christian Textbooks country. This book tries to talk about traditional religion more generally, (ACTS), PMB 2020, Bukuru 930008, Plateau State, Nigeria. Reissued in this format with the permission of the author and publisher by exploring some of the religious ideas found in ethnic groups that do not Tamarisk Publications, 2014. have much of the gospel yet. Most textbooks on Traditional Religion web: www.opaltrust.org describe the religion without relating it to the teachings of the Bible. email: [email protected] However a missionary needs to know how to relate the Bible’s teaching to traditional beliefs. Lois K. Fuller has taught in schools of mission and theological colleges across This book is also about methods we can use to interest followers of ATR many denominations in Nigeria. She served for some years as Dean of Nigeria in the gospel and teach and disciple them so that they will understand the Evangelical Missionary Institute (NEMI). -

40 Days of Devotion

BEGIN PRAYING FOR MARCH 13 40 DAYS OF DEVOTION THE PEOPLE OF GUINEA Proclaim the Power of God to Save — Kissi People, Susu People, I Corinthians 1:18 Our goal is to join the Disciple Making Movements currently underway. Mandinka People — We are devoting 40 days of prayer, so that we may be united as we join MARCH 14 this world-wide spiritual awakening. We want to support people who love MARCH 3 * Seek to Reconcile Others to God Christ, submit to Scriptures, and love one another. Disciples Surrender to the Father’s II Corinthians 5:18-19 Sovereignty | Proverbs 3:5-6 Please join us on this 40 day journey. MARCH 15 MARCH 4 Give Sacrificially | I Corinthians 9:19 Disciples Surrender to Christ’s Teaching FEBRUARY 12 FEBRUARY 23 Matthew 5:19 MARCH 16 A World-Wide Awakening | Acts 1:8 Disciples are not Afraid to Die for Jesus Confess Unresolved Sin | I John 1:8-9 Acts 21:1-14 MARCH 5 FEBRUARY 13 Disciples Surrender to the Spirit’s BEGIN PRAYING FOR Prayer and Fasting | Acts 13:1-3 FEBRUARY 24 guidance | Romans 8:14 THE PEOPLE OF SENEGAL God Helps Disciples Endure Persecution — Wolof & Fulani Peoples — FEBRUARY 14 Acts 18:1-11 BEGIN PRAYING FOR Love for Others | Col 3:12-14 THE PEOPLE OF CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC BEGIN PRAYING FOR MARCH 17 * FEBRUARY 15 THE PEOPLE OF NIGER — Mandja People — Disciples Place Their Trust in God Alone Matthew 7:11 Persons of Peace | Luke 10:5-9 — Gourmanche People, Hausa People, MARCH 6 Tuareg People — Disciples Seek Him Through Prayer MARCH 18 FEBRUARY 16 Matthew 7:7-8 FEBRUARY 25 * Disciples Trust in God to Answer -

Changements Institutionnels, Statégies D'approvisionnement Et De Gouvernance De L'eau Sur Les Hautes Terres De L'ou

Changements institutionnels, statégies d’approvisionnement et de gouvernance de l’eau sur les hautes terres de l’Ouest Cameroun : exemples des petites villes de Kumbo, Bafou et Bali Gillian Sanguv Ngefor To cite this version: Gillian Sanguv Ngefor. Changements institutionnels, statégies d’approvisionnement et de gouvernance de l’eau sur les hautes terres de l’Ouest Cameroun : exemples des petites villes de Kumbo, Bafou et Bali. Géographie. Université Toulouse le Mirail - Toulouse II, 2014. Français. NNT : 2014TOU20006. tel-01124258 HAL Id: tel-01124258 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01124258 Submitted on 6 Mar 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 5)µ4& &OWVFEFMPCUFOUJPOEV %0$503"5%&-6/*7&34*5²%&506-064& %ÏMJWSÏQBS Université Toulouse 2 Le Mirail (UT2 Le Mirail) $PUVUFMMFJOUFSOBUJPOBMFBWFD 1SÏTFOUÏFFUTPVUFOVFQBS NGEFOR Gillian SANGUV -F mercredi 29 janvier 2014 5Jtre : INSTITUTIONAL CHANGES, WATER ACCESSIBILITY STRATEGIES AND GOVERNANCE IN THE CAMEROON WESTERN HIGHLANDS: THE CASE OF BALI, KUMBO AND BAFOU SMALL CITIES. École doctorale -

December 2018 Prayer Calendar

Rev. Claude and Rhoda Houge are seasoned missionaries, having served as literacy supervisors with Lutheran Bible Translators in Liberia, West Africa, from 1982-1992. They also served in Ghana and Kenya with LCMS World Mission for 13 years. They are both graduates of Concordia University in Seward, NebrasKa. Claude served in the LCMS as a teacher, lay minister and pastor. Rhoda has been a teacher, business manager, office manager, volunteer coordinator and homemaker. While the Houges’ main focus is homeschooling, they will also assist with The Houges are using their experience and education to member care – the emotional, mental and homeschool the children of Rev. David and Valerie Federwitz in northern Ghana. Pictured is Rev. Claude spiritual support of missionaries. Claude will Houge working with the Federwitz children. also be available to perform other pastoral duties as requested. December Birthdays Isaac Esala Judah Grulke Paul Federwitz Joan Weber Serena Derricks Josiah Wagner Josh Wagner Mical Hilbert lbt.org · 660-225-0810 · [email protected] Lutheran Bible Translators PO Box 789 Concordia MO 64020 1. Pray for God's blessings upon HR manager 11. Pray for Becky Grossmann as she 22. Praise God for the dedication of the staff Melissa Schweigert as she celebrates her first prepares to give her doctoral defense on of LBT Gift Records and pray that they will birthday as a new mother. December 12. have renewed energy during the busy holiday 2. Pray for Rev. Claude Houge as he teaches 12. Prayers of thanksgiving for Judah Grulke and end of the year time. JoyAnna and Micah Federwitz in Ghana. -

National Community Driven Development Program-PNDP

Santa Council COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT PLAN Approved by: Santa Council Development plan-CDP Page 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Within the framework of Cameroon Vision 2035, the growth and employment strategy and the decentralisation process in Cameroon with focus on local governance, councils are therefore expected to assume the full responsibility to manage resources and projects within their areas of jurisdiction. These resources are coming from Government, technical and financial partners as well as those mobilised locally. The Government through some of her sectorial ministries have already in the first generation devolved some resources and competences to councils serving as a trial to measure their level in the areas of project execution and management. The innovation of instituting a bottom-up approach of development whereby the populations at the grassroots are called upon to get totally involved and participate in the identification of their own problems, translate them into micro projects becomes capital to the elaboration of a council development plan. The Council Development plan (CDP) is a document that presents the desired goal, objectives, actions and the activities that the council wants to realize within a period. The CDP is elaborated in a participatory manner based on information obtained from village level, urban level and institutional diagnosis which are consolidated. As such it involved various partners; the National Community Driven Development Program (PNDP) that offered technical and financial resources, the Support Service to Grassroots Initiatives of Development (SAILD) that was privileged to provide services to the Santa Council for various studies, the Santa Council and inhabitants of constituent villages who provided the data required for the studies, and various sectorial ministries within the municipality, Division and the Region who equally provided data and assisted in the analysis and elaboration of planning tables. -

European Colonialism in Cameroon and Its Aftermath, with Special Reference to the Southern Cameroon, 1884-2014

EUROPEAN COLONIALISM IN CAMEROON AND ITS AFTERMATH, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE SOUTHERN CAMEROON, 1884-2014 BY WONGBI GEORGE AGIME P13ARHS8001 BEING A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, NIGERIA, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS (MA) DEGREE IN HISTORY SUPERVISOR PROFESSOR SULE MOHAMMED DR. JOHN OLA AGI NOVEMBER, 2016 i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this Dissertation titled: European Colonialism in Cameroon and its Aftermath, with Special Reference to the Southern Cameroon, 1884-2014, was written by me. It has not been submitted previously for the award of Higher Degree in any institution of learning. All quotations and sources of information cited in the course of this work have been acknowledged by means of reference. _________________________ ______________________ Wongbi George Agime Date ii CERTIFICATION This dissertation titled: European Colonialism in Cameroon and its Aftermath, with Special Reference to the Southern Cameroon, 1884-2014, was read and approved as meeting the requirements of the School of Post-graduate Studies, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, for the award of Master of Arts (MA) degree in History. _________________________ ________________________ Prof. Sule Mohammed Date Supervisor _________________________ ________________________ Dr. John O. Agi Date Supervisor _________________________ ________________________ Prof. Sule Mohammed Date Head of Department _________________________ ________________________ Prof .Sadiq Zubairu Abubakar Date Dean, School of Post Graduate Studies, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to God Almighty for His love, kindness and goodness to me and to the memory of Reverend Sister Angeline Bongsui who passed away in Brixen, in July, 2012. -

Cameroon Version 4 Clean#2

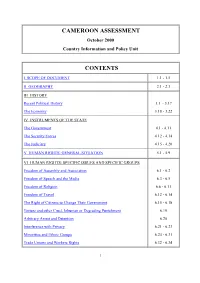

CAMEROON ASSESSMENT October 2000 Country Information and Policy Unit CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.3 III HISTORY Recent Political History 3.1 - 3.17 The Economy 3.18 - 3.22 IV INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE The Government 4.1 - 4.11 The Security Forces 4.12 - 4.14 The Judiciary 4.15 - 4.20 V HUMAN RIGHTS: GENERAL SITUATION 5.1 - 5.9 VI HUMAN RIGHTS: SPECIFIC ISSUES AND SPECIFIC GROUPS Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.1 - 6.2 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.3 - 6.5 Freedom of Religion 6.6 - 6.11 Freedom of Travel 6.12 - 6.14 The Right of Citizens to Change Their Government 6.15 - 6.18 Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Punishment 6.19 Arbitrary Arrest and Detention 6.20 Interference with Privacy 6.21 - 6.23 Minorities and Ethnic Groups 6.24 - 6.31 Trade Unions and Workers Rights 6.32 - 6.34 1 Human Rights Groups 6.35 - 6.36 Women 6.36 - 6.41 Children 6.42 - 6.45 Treatment of Refugees 6.46 - 6.48 ANNEX A: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS Pages 19 - 22 ANNEX B: PROMINENT PEOPLE Page 23 ANNEX C: CHRONOLOGY Pages 24 - 27 ANNEX D: BIBLIOGRAPHY Pages 28 - 29 I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process. -

Performance and Performativity in Pastoral Fulbe Culture

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Tea Virtanen PERFORMANCE AND PERFORMATIVITY IN PASTORAL FULBE CULTURE Research Series in Anthropology University of Helsinki Academic Dissertation Research Series in Anthropology University of Helsinki, Finland Distributed by: Helsinki University Press PO Box 4 (Vuorikatu 3A) 00014 University of Helsinki Finland Fax: + 358-9-70102374 www.yliopistopaino.helsinki.fi Copyright © 2003 Tea Virtanen ISSN 1458-3186 ISBN (print.) 952-10-1397-4 ISBN (pdf) 952-10-1398-2 http://ethesis.helsinki.fi Helsinki University Printing House Helsinki 2003 To the Memory of Alhaji Kongoro Each world whilst it is attended to is real after its own fashion. William James CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgements viii 1. Introduction 1 Shifting Perspectives 1 Gathering Information 7 From Cultural Performances towards the Performativity of Culture 10 Outline 23 2. Pulaaku: Performed or Embodied Culture? 25 Pulaaku, Performance and Shame 27 Pulaaku as Cultural Competence 31 Sharing Shame and Ideals 34 “Is Your Body Well?”: Pulaaku in Greetings 36 On How the Fulbe Greet 37 Greeting as a Model for Smooth Interaction 40 Reframing the Greeting Performance 42 3. People of the Blessed Cattle 48 Nomads, Jihad and the Process of Sedentarisation 48 Fulbe Routes to Cameroon 50 The Formation of Muslim Fulbe Chiefdoms in Adamawa 51 The Migration of the Cattle Fulbe to Cameroon 58 Tibati: Excursion into Local History 63 Later Arrivals: The Aku Wave of the 1970s 70 The Blessed Cattle 81 iv Contents 4. Recollecting Nigeria: Myth and History in the Present 85 Reshaping the Origins 85 “We Come after Arabs” 86 From Town to Bush 90 Creation of the Cattle 92 Myths and Islam in Adamaoua 96 Performing a Mythical History 99 Recollecting Nigeria 101 The Unspoken Pre-Muslim Past 102 The Two Landscapes 106 From Soro to Manslaughter: Cameroon and the Undisciplined Youth 113 Change and Continuity in Campsites 121 History in the Present 126 5. -

Africa Nigeria 100580000

1 Ethnologue: Areas: Africa Nigeria 100,580,000 (1995). Federal Republic of Nigeria. Literacy rate 42% to 51%. Information mainly from Hansford, Bendor-Samuel, and Stanford 1976; J. Bendor-Samuel, ed., 1989; CAPRO 1992; Crozier and Blench 1992. Locations for some languages indicate new Local Government Area (LGA) names, but the older Division and District names are given if the new names are not yet known. Also includes Lebanese, European. Data accuracy estimate: A2, B. Also includes Pulaar Fulfulde, Lebanese, European. Christian, Muslim, traditional religion. Blind population 800,000 (1982 WCE). Deaf institutions: 22. The number of languages listed for Nigeria is 478. Of those, 470 are living languages, 1 is a second language without mother tongue speakers, and 7 are extinct. ABINSI (JUKUN ABINSI, RIVER JUKUN) [JUB] Gongola State, Wukari LGA, at Sufa and Kwantan Sufa; Benue State, Makurdi Division, Iharev District at Abinsi. Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Platoid, Benue, Jukunoid, Central, Jukun-Mbembe-Wurbo, Kororofa. In Kororofa language cluster. Traditional religion. Survey needed. ABONG (ABON, ABO) [ABO] 1,000 (1973 SIL). Taraba State, Sardauna LGA, Abong town. Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Bantoid, Southern, Tivoid. Survey needed. ABUA (ABUAN) [ABN] 25,000 (1989 Faraclas). Rivers State, Degema and Ahoada LGA's. Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Cross River, Delta Cross, Central Delta, Abua-Odual. Dialects: CENTRAL ABUAN, EMUGHAN, OTABHA (OTAPHA), OKPEDEN. The central dialect is understood by all others. Odual is the most closely related language, about 70% lexical similarity. NT 1978. Bible portions 1973. ACIPA, EASTERN (ACIPANCI, ACHIPA) [AWA] 5,000 (1993). -

Kamwe (Higgi) Origin(S), Migration(S) and Settlement

Journal of African Studies and Sustainable Development. Vol.1, No.2. 2018. ISSN Online: 2630-7073, ISSN Print 2630-7065. www.apas.org.ng/journals.asp KAMWE (HIGGI) ORIGIN(S), MIGRATION(S) AND SETTLEMENT BAZZA, Michael Boni Department of History and International Relations Veritas University Abuja (The Catholic University of Nigeria) & Prof. KANU Ikechukwu Anthony Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies Tansian University, Umunya Abstract The concept of ‘genesis’ or ‘origin’ in history has given rise to several schools of thought each seeking to provide a framework through which the origin of people could be meaningfully examined. These include the Diffusionist, Anti-Diffusionist, Procreationist, and Evolutionist schools of thought. This paper therefore, examines each of these schools with a view to situating Kamwe (Higgi) origin(s) migration(s) and settlement patterns in their proper historical perspectives. An analysis of the aforementioned schools of thought reveal that the Kamwe (Higgi) people fit more adequately within the framework of the Evolutionist school of thought which maintains that socio-cultural affinities emerging from shared historical experience over time, constitute the bedrock for understanding the origins of people. Oral traditions and opinions of elders from the field of research convey the fact that the people who today answer to the designation ‘Kamwe or Higgi’ were in the earliest times, a collection of small socio-cultural units of the Sukur, the Marghi and Fali; essentially, they inhabit modern day Michika, Madagali and Mubi North Local Government Areas and indeed, the Mandara Mountains’ range lying immediately aside the Nigeria-Cameroun border. However, over time, these socio-cultural units coalesced by sheer forces of history such as wars, inter-marriage, trade and commerce and subsequently developed a number of shared cultural characteristics which today distinguish them as member of a common nation. -

A Guide to the Musical Instruments of Cameroun: Classification, Distribution, History and Vernacular Names

A guide to the musical instruments of Cameroun: classification, distribution, history and vernacular names [DRAFT CIRCULATED FOR COMMENT -NOT FOR CITATION WITHOUT REFERENCE TO THE AUTHOR Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This printout: July 31, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS.................................................................................................................................I PHOTOS ........................................................................................................................................................IV MAPS .............................................................................................................................................................VI PREFACE.................................................................................................................................................... VII 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 General .................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Indigenous and Western classifications .................................................................................................