1 SUSTAINABILITY of the COMPOSTING TOILET by Anna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Non-Incineration Medical Waste Treatment Technologies

Non-Incineration Medical Waste Treatment Technologies A Resource for Hospital Administrators, Facility Managers, Health Care Professionals, Environmental Advocates, and Community Members August 2001 Health Care Without Harm 1755 S Street, N.W. Unit 6B Washington, DC 20009 Phone: 202.234.0091 www.noharm.org Health Care Without Harm 1755 S Street, N.W. Suite 6B Washington, DC 20009 Phone: 202.234.0091 www.noharm.org Printed with soy-based inks on Rolland Evolution, a 100% processed chlorine-free paper. Non-Incineration Medical Waste Treatment Technologies A Resource for Hospital Administrators, Facility Managers, Health Care Professionals, Environmental Advocates, and Community Members August 2001 Health Care Without Harm www.noharm.org Preface THE FOUR LAWS OF ECOLOGY . Meanwhile, many hospital staff, such as Hollie Shaner, RN of Fletcher-Allen Health Care in Burlington, Ver- 1. Everything is connected to everything else, mont, were appalled by the sheer volumes of waste and 2. Everything must go somewhere, the lack of reduction and recycling efforts. These indi- viduals became champions within their facilities or 3. Nature knows best, systems to change the way that waste was being managed. 4. There is no such thing as a free lunch. Barry Commoner, The Closing Circle, 1971 In the spring of 1996, more than 600 people – most of them community activists – gathered in Baton Rouge, Up to now, there has been no single resource that pro- Louisiana to attend the Third Citizens Conference on vided a good frame of reference, objectively portrayed, of Dioxin and Other Hormone-Disrupting Chemicals. The non-incineration technologies for the treatment of health largest workshop at the conference was by far the one care wastes. -

Reducing the Food Wastage Footprint

toolkit.xps:Layout 1 13/06/13 11.44 Pagina 3 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-107741-2 (print) E-ISBN 978-92-5-107743-6 (PDF) © FAO 2013 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact- us/licence-request or addressed to [email protected]. FAO information products are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/publications) and can be purchased through publications- [email protected]. -

Medical Waste Treatment Technologies

Medical Waste Treatment Technologies Ruth Stringer International Science and Policy Coordinator Health Care Without Harm Dhaka January 2011 Who is Health Care Without Harm? An International network focussing on two fundamental rights: • Right to healthcare • Right to a healthy environment Health Care Without Harm • Issues • Offices in – Medical waste –USA –Mercury – Europe – PVC – Latin America – Climate and health – South East Asia – Food • Key partners in – Green buildings –South Africa – Pharmaceuticals – India –Nurses – Tanzania – Safer materials –Mexico • Members in 53 countries Global mercury phase-out • HCWH and WHO partnering to eliminate mercury from healthcare • Part of UN Environment Programme's Mercury Products Partnership. • www.mercuryfreehealthcare.org • HCWH and WHO are principal cooperating agencies • 8-country project to reduce impacts from medical waste – esp dioxins and mercury • Model hospitals in Argentina, India, Latvia, Lebanon, the Philippines, Senegal and Vietnam • Technology development in Tanzania Incineration No longer a preferred treatment technology in many places Meeting modern emission standards costs millions of dollars Ash must be treated as hazardous waste Small incinerators are highly polluting Maintenance costs can be high, breakdowns common Decline in Medical Waste Incinerators in the U.S. 8,000 6,200 6,000 5,000 4,000 2,400 2,000 Incinerators 115 83 57 #of Medical Waste Waste Medical #of 0 1988 1994 1997 2003 2006 2008 Year SOURCES: 1988: “Hospital Waste Combustion Study-Data Gathering Phase,” USEPA, December 1998; 1994: “Medical Waste Incinerators-Background Information for Proposed Standards and Guidelines: Industry Profile Report for New and Existing Facilities,” USEPA, July 1994; 1997: 40 CFR 60 in the Federal Register, Vol. -

Designing an Evaluation Protocol for Composting Toilet Systems ______

Designing an Evaluation Protocol for Composting Toilet Systems ______________________________________________________________ An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science. By: Camryn Berry Zahava Preil Lena Sophia Thompson Date: February 26, 2020 Report Submitted to: Professor Seth Tuler and Professor Isa Bar-On This report represents work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, see http://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects Abstract Two billion people worldwide lack access to adequate sanitation which ensures hygienic separation of human excreta from human contact. Composting toilets help address this health hazard by containing waste and reducing risk of disease. The goal of our project was to develop a cost-effective, user-friendly and minimally-disruptive protocol to evaluate the function, use and maintenance of composting toilets. This protocol was trialed at Kibbutz Lotan in Israel. We concluded that Lotan’s system was effective, though inefficient. The trial allowed us to identify potential improvements to the protocol that can be applied in the future. Our protocol is successful for evaluating the success of a system and how adequately it can address the unnecessary loss of life caused by inadequate sanitation. ii Acknowledgements We would like to thank the people who helped make our project possible. Firstly, we would like to thank our sponsor Alex Cicelsky of the Kibbutz Lotan Center for Creative Ecology. -

“Sustainable” Sanitation: Challenges and Opportunities in Urban Areas

sustainability Review Towards “Sustainable” Sanitation: Challenges and Opportunities in Urban Areas Kim Andersson *, Sarah Dickin and Arno Rosemarin Stockholm Environment Institute, Linnégatan 87D, 115 23 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected] (S.D.); [email protected] (A.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +46-73-707-8609 Academic Editors: Philipp Aerni and Amy Glasmeier Received: 8 June 2016; Accepted: 2 December 2016; Published: 8 December 2016 Abstract: While sanitation is fundamental for health and wellbeing, cities of all sizes face growing challenges in providing safe, affordable and functional sanitation systems that are also sustainable. Factors such as limited political will, inadequate technical, financial and institutional capacities and failure to integrate safe sanitation systems into broader urban development have led to a persistence of unsustainable systems and missed opportunities to tackle overlapping and interacting urban challenges. This paper reviews challenges associated with providing sanitation systems in urban areas and explores ways to promote sustainable sanitation in cities. It focuses on opportunities to stimulate sustainable sanitation approaches from a resource recovery perspective, generating added value to society while protecting human and ecosystem health. We show how, if integrated within urban development, sustainable sanitation has great potential to catalyse action and contribute to multiple sustainable development goals. Keywords: urbanization; sustainable sanitation; resource recovery; urban planning and development; public health 1. Introduction Sanitation is fundamental to healthy and productive urban life, and the provision of sanitation services for fast-growing urban populations is one of the world’s most urgent challenges. Currently, more than 700 million urban residents lack improved sanitation access globally, including 80 million who practise open defecation [1]. -

Workplace Recycling

SETTING UP Workplace Recycling 1 Form a Enlist a group of employees interested in recycling and waste prevention to set up and monitor collection systems Recycling Team to ensure ongoing success. This is a great team-building exercise and can positively impact employee morale as well as the environment. 2 Determine Customize your recycling program based on your business. Consider performing a waste audit or take inventory of materials the kinds of materials in your trash & recycling. to recycle Commonly recycled business items: Single-Stream Recycling • Aluminum & tin cans; plastic & glass bottles • Office paper, newspaper, cardboard • Magazines, catalogs, file folders, shredded paper 3 Contact Find out if recycling services are already in place. If not, ask the facility or property manager to set them up. Point your facility out that in today’s environment, employees expect to recycle at work and that recycling can potentially reduce costs. If recycling is currently provided, check with the manager to make sure good recycling education materials or property are available to all employees. This will help employees to recycle right, improve the quality of recyclable materials, manager and increase recycling participation. 4 Coordinate Work station recycling containers – Provide durable work station recycling containers or re-use existing training containers like copy paper boxes. Make recycling available at each work station. with the Click: Get-Started-Recycling-w_glass or Get-Started-Recycling-without-glass to print recycling container labels. Label your trash containers as well: Get-Started-Trash-with-food waste or janitorial crew Get-Started-Trash -no-food waste. and/or staff Central area containers – Evaluate the type and size of containers for common areas like conference rooms, hallways, reception areas, and cafes, based on volume, location, and usage. -

Archaeologies of Race and Urban Poverty: The

33 Paul R. Mullins accessed from the ground level or a second-floor Lewis C. Jones walkway that extended into the yard, where the large outhouse loomed over the neighboring out- buildings and even some of the nearby homes. Archaeologies of Race and The outhouse remained in the yard until just Urban Poverty: The Politics after 1955, when it was finally dismantled not of Slumming, Engagement, long before most of the block itself was razed. In 1970 an administrator at Indiana University- and the Color Line Purdue University, Indianapolis (IUPUI) described the outhouse as an “architectural and engineer- ABSTRACT ing marvel,” but by then the outhouse had been dismantled for 15 years and its brick foundation For more than a century, social reformers and scholars have sat beneath a university parking lot. In the sub- examined urban impoverishment and inequalities along the color sequent years the outhouse has fascinated faculty, line and linked “slum life” to African America. An engaged students, and community members, but most of archaeology provides a powerful mechanism to assess how urban-renewal and tenement-reform discourses were used to that fascination has revolved around the mechan- reproduce color and class inequalities. Such an archaeology ics of the tower, fostering a string of jokes about should illuminate how comparable ideological distortions are which campus constituency deserved the upper- wielded in the contemporary world to reproduce longstand- story seat (Gray 2003:43). The superficial humor ing inequalities. A 20th-century neighborhood in Indianapolis, in the outhouse discourse reflects understandable Indiana, is examined to probe how various contemporary con- stituencies borrow from, negotiate, and refute long-established wonder about the structure as an engineering urban impoverishment and racial discourses and stake claims feat as well as curiosity about such a seemingly to diverse present-day forms of community heritage. -

Sector N: Scrap and Waste Recycling

Industrial Stormwater Fact Sheet Series Sector N: Scrap Recycling and Waste Recycling Facilities U.S. EPA Office of Water EPA-833-F-06-029 February 2021 What is the NPDES stormwater program for industrial activity? Activities, such as material handling and storage, equipment maintenance and cleaning, industrial processing or other operations that occur at industrial facilities are often exposed to stormwater. The runoff from these areas may discharge pollutants directly into nearby waterbodies or indirectly via storm sewer systems, thereby degrading water quality. In 1990, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) developed permitting regulations under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) to control stormwater discharges associated with eleven categories of industrial activity. As a result, NPDES permitting authorities, which may be either EPA or a state environmental agency, issue stormwater permits to control runoff from these industrial facilities. What types of industrial facilities are required to obtain permit coverage? This fact sheet specifically discusses stormwater discharges various industries including scrap recycling and waste recycling facilities as defined by Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) Major Group Code 50 (5093). Facilities and products in this group fall under the following categories, all of which require coverage under an industrial stormwater permit: ◆ Scrap and waste recycling facilities (non-source separated, non-liquid recyclable materials) engaged in processing, reclaiming, and wholesale distribution of scrap and waste materials such as ferrous and nonferrous metals, paper, plastic, cardboard, glass, and animal hides. ◆ Waste recycling facilities (liquid recyclable materials) engaged in reclaiming and recycling liquid wastes such as used oil, antifreeze, mineral spirits, and industrial solvents. -

What Happens When We Flush?

Anthropology Now ISSN: 1942-8200 (Print) 1949-2901 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/uann20 What Happens When We Flush? Nicholas C. Kawa To cite this article: Nicholas C. Kawa (2016) What Happens When We Flush?, Anthropology Now, 8:2, 34-43 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19428200.2016.1202580 Published online: 29 Sep 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 17 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=uann20 Download by: [Tufts University] Date: 04 January 2017, At: 14:38 features reach far into our houses with their tentacles, they are carefully hidden from view, and we are happily ignorant of the invisible Venice What Happens When of shit underlying our bathrooms, bedrooms, dance halls, and parliaments.”1 We Flush? So what really happens when the mod- ern toilet goes “flush”? The human excreta it Nicholas C. Kawa handles most certainly does not disappear. Instead, a potential resource is turned into waste. But it hasn’t always been this way, and ost people who use a flush toilet prob- it doesn’t have to be. Mably don’t spend a lot of time thinking about where their bodily fluids and solids will journey after they deposit them. This is be- Dark Earths and Night Soils cause modern sanitation systems are designed to limit personal responsibilities when it Much of my research as an environmental comes to managing these most intimate forms anthropologist has focused on human rela- of excreta. -

HEALTH ASPECTS of DRY SANITATION with WASTE REUSE Anne Peasey

HEALTH ASPECTS OF DRY SANITATION WITH WASTE REUSE Anne Peasey Task No. 324 WELL STUDIES IN WATER AND ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH Health Aspects of Dry Sanitation with Waste Reuse Anne Peasey WELL Water and Environmental Health at London and Loughborough Health Aspects of Dry Sanitation with Waste Reuse ii London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Keppel Street London WC1E 7HT © LSHTM/WEDC Peasey, A. (2000) Health Aspects of Dry Sanitation with Waste Reuse WELL Designed and Produced at LSHTM Health Aspects of Dry Sanitation with Waste Reuse EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BACKGROUND Dry sanitation is defined in this report as the on-site disposal of human urine and faeces without the use of water as a carrier. This definition includes many of the most popular options for low- cost sanitation including pit latrines, Ventilated Improved Pits, SanPlats, etc. There has always been an interest in the reuse of human waste as a fertiliser, and there has been much recent work on the development of composting and other processes to permit human waste reuse. This report examines the practice of dry sanitation with reuse in Mexico, with a particular focus on health issues and the lessons to be learned from case studies and experience. DRY SANITATION WITH REUSE There are two distinct technical approaches to dry sanitation with reuse; · Dehydration. Urine and faeces are managed separately. The deposited faecal matter may be dried by the addition of lime, ash, or earth, and the contents are simply isolated from human contact for a specified period of time to reduce the presence of pathogens. · Decomposition (composting) In this process, bacteria, worms, or other organisms are used to break organic matter down to produce compost. -

UD & Composting Toilets (Ecosan)

UD Toilets and Composting Toilets in Emergency Settings This Technical Brief looks at the criteria for selecting Urine Diversion (UD) and Composting Toilets options in an emergency setting, including the construction, operation and maintenance of such units which is used to store and dry the faeces over a specified Ecological Sanitation or period. Normally, it is recommended to store faeces for a Sustainable Sanitation? minimum of 12-months in one vault before emptying. Adding a desiccating material such as ash or sawdust will The approach of Ecological Sanitation (Ecosan) in accelerate the faeces drying process. Typically, in a well- emergency settings breaks with conventional excreta managed ecosan unit, storage times of greater than 3- disposal options such as pit latrines or pour-flush toilets. months will reduce many pathogens to safe levels, in Traditionally, Ecosan systems re-use both faeces and particular those responsible for Ameobiasis, Giardiasis, urine, turning them into either a soil conditioner or a Hepatitis A, Hookworm, Whipworm, Threadworm, fertilizer. This not only benefits peoples’ health through Rotavirus, Cholera, Escherichia coli, and Typhoid safe excreta disposal and by reducing environmental amongst others. Ascaris is more persistent though, and contamination, but also implies re-using the by-products may require retention times of 12-months or more. for some form of agricultural activity. In an emergency setting, the choice of ecosan options is very often driven by factors other than the re-use of all or part of the by-products. Ecosan toilets are very often better suited to rocky ground or areas with high water tables, making them more resistant to cyclic flooding for instance. -

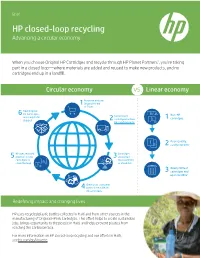

HP Closed-Loop Recycling Advancing a Circular Economy

• Brief HP closed-loop recycling Advancing a circular economy When you choose Original HP Cartridges and recycle through HP Planet Partners1, you’re taking part in a closed loop—where materials are added and reused to make new products, and no cartridges end up in a landfill. Circular economy vs. Linear economy Purchase and use 1 Original HP Ink or Toner New Original HP Cartridges 6 Return used Non-HP are ready to be 1 cartridges shipped 2 cartridges for free hp.com/hprecycle Poor-quality, 2 costly reprints2 HP uses recycled Cartridges 5 plastics3 in new 3 are sorted, cartridges to disassembled, close the loop or shredded Nearly 90% of 3 cartridges end up in landfills4 Other post-consumer 4 plastics are added to ink cartridges Redefining impact and changing lives HP uses recycled plastic bottles collected in Haiti and from other sources in the manufacturing of Original HP Ink Cartridges. This effort helps to create sustainable jobs, brings opportunity to the people in Haiti, and helps prevent plastics from reaching the Caribbean Sea. For more information on HP closed-loop recycling and our efforts in Haiti, see hp.com/go/Rosette. Together, we’re recycling for a better world The results speak for themselves. Here’s the difference HP made in 2018 by using recycled plastic in ink cartridges instead of new plastic: 60% reduction 39% less 30% average in fossil fuel water used5 carbon footprint consumption5 Enough to supply reduction5 Conserved more than 7.9 million Americans Like taking 533 cars off 7 6 for one day 8 705 barrels of oil the road for one year Bringing used products back to life With your help, we’re closing the loop.