The Crash of Korean Air Lines Flight 007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Southern Airlines' Sky Pearl Club

SKY PEARL CLUB MEMBERSHIP GUIDE Welcome to China Southern Airlines’ Sky Pearl Club The Sky Pearl Club is the frequent flyer program of China Southern Airlines. From the moment you join The Sky Pearl Club, you will experience a whole new world of exciting new travel opportunities with China Southern! Whether you’re traveling for business or pleasure, you’ll be earning mileage toward your award goals every time you fly. Many Elite tier services have been prepared for you. We trust this Guide will soon help you reach your award flight to your dream destinations. China Southern Sky Pearl Club cares about you! 1 A B Earning Sky Pearl Mileage Redeeming Sky Pearl Mileage Airlines China Southern Award Ticket and Award Upgrade Hotels SkyTeam Award Ticket and Award Upgrade Banks Telecommunications, Car Rentals, Business Travel , Dining and others C D Getting Acquainted with Sky Pearl Rules Enjoying Sky Pearl Elite Benefits Definition Membership tiers Membership Qualification and Mileage Account Elite Qualification Mileage Accrual Elite Benefits Mileage Redemption Membership tier and Elite benefits Others 2 A Earning Sky Pearl Mileage As the newest member of the worldwide SkyTeam alliance, whether it’s in the air or on the ground, The Sky Pearl Club gives you more opportunities than ever before to earn Award travel. When flying with China Southern or one of our many airline partners, you can earn FFP mileage. But, that’s not the only way! Hotels stays, car rentals, credit card services, telecommunication services or dining with our business-to-business partners can also help you earn mileage. -

Special Cargo, Special Solutions Transportation of Special Cargo Is One of Korean Air's Expertise

special cargo, special solutions Transportation of special cargo is one of Korean Air's expertise We are particularly proud of our high standards and quality services in transporting special shipments. Since inception in 1969, Korean Air Cargo has handled nearly every commodity imaginable - from fresh tulips to dolphins, from tiny electronic chips to gigantic oil drilling equipment. Variation is well designed to offer new solutions for you, utilizing our long accumulated knowledge and confidence in specialized cargo handling. A range of eleven Variation products specifically meet the needs of each type of goods, guaranteeing quality service at all times Variation-ART is designed for handling precious works of art, focusing on protection from humidity, shock and water damage. Variation-BIG is designed to accommodate extremely oversized or heavy pieces that require freighter aircraft. Variation-DGR is a specialty product for the dangerous goods shipment, designed under strict compliance with IATA standards and regulations. Variation-FASHION is dedicated to the shipment of garment on hangers and provides special sealed containers for quick delivery. Variation-FRESH is designed to meet the needs of shippers handling temperature- sensitive cargo: FRESH 1, 2, 3. Variation-LIVE is designed to ensure the safety and health of live animals. Variation-SAFE is designed for handling cargo of high value: SAFE 1, 2. Variation-WHEELS is designed for motorized vehicles ranging from motorcycles to automobiles. Variation-ART provides specialized logistical service to transport artwork in optimum conservation and security conditions ● Handled with special care during ground transportation at each airport to ensure minimum impact. ● Customers can be allowed to watch entire ground handling processes. -

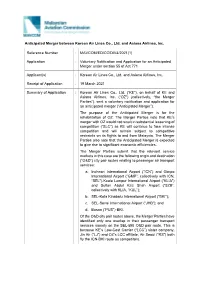

Consultation on the Application of an Anticipated Merger Between Korean Air Lines Co., Ltd. and Asiana

Anticipated Merger between Korean Air Lines Co., Ltd. and Asiana Airlines, Inc. Reference Number : MAVCOM/ED/CC/DIV4/2021(1) Application : Voluntary Notification and Application for an Anticipated Merger under section 55 of Act 771 Applicant(s) : Korean Air Lines Co., Ltd. and Asiana Airlines, Inc. Receipt of Application : 19 March 2021 Summary of Application : Korean Air Lines Co., Ltd. (“KE”), on behalf of KE and Asiana Airlines, Inc. (“OZ”) (collectively, “the Merger Parties”), sent a voluntary notification and application for an anticipated merger (“Anticipated Merger”). The purpose of the Anticipated Merger is for the rehabilitation of OZ. The Merger Parties note that KE’s merger with OZ would not result in substantial lessening of competition (“SLC”) as KE will continue to face intense competition and will remain subject to competitive restraints on its flights to and from Malaysia. The Merger Parties also note that the Anticipated Merger is expected to give rise to significant economic efficiencies. The Merger Parties submit that the relevant service markets in this case are the following origin and destination (“O&D”) city pair routes relating to passenger air transport services: a. Incheon International Airport (“ICN”) and Gimpo International Airport (“GMP”, collectively with ICN, “SEL”)-Kuala Lumpur International Airport (“KLIA”) and Sultan Abdul Aziz Shah Airport (“SZB”, collectively with KLIA, “KUL”); b. SEL-Kota Kinabalu International Airport (“BKI”); c. SEL-Senai International Airport (“JHB”); and d. Busan (“PUS”)-BKI. Of the O&D city pair routes above, the Merger Parties have identified only one overlap in their passenger transport services namely on the SEL-BKI O&D pair route. -

International Destinations and Flights Departing from Centrair

International Network @ Centrair As of March 27, 2014 Weekly Frequency of International Flights Airline Route 2014Summer 2013Winter 2013Summer (3/30-10/25) (10/27-3/29) (3/31-10/26) Remarks Planned Results Results April 2014Summer 23 # of destinations: Apr 2014S 27 (Passenger 21 ,Freighter 4) (excluding Narita) Apr Mar Aug Korean Air (KE) Seoul (Incheon) (ICN) 18 18 14 Asiana Airlines (OZ) Seoul (Incheon) (ICN) 14 14 14 Jeju Air (7C) Seoul (Gimpo) (GMP) 7 7 7 Jeju Air (7C) Seoul (Incheon) (ICN) 7 7 7 AirAsia Japan (JW) Seoul (Incheon) (ICN) - - 7 Korean Air (KE) Pusan (PUS) 7 7 7 Korean Air (KE) Cheju (CJU) 3 3 4 Korea 3 destinations 56 56 60 China Southern Airlines (CZ) Changchun (CGQ) 2 2 2 China Southern Airlines (CZ) Dalian (DLC) 7 7 7 Air China (CA) Beijing (PEK) 7 7 7 Etihad Airways (EY) Beijing (PEK) ー Abu Dhabi (AUH) (5) (5) (5) Japan Airlines (JL) Shanghai (PVG) 7 7 7 China Eastern Airlines (MU) Shanghai (PVG) 14 14 14 All Nippon Airways (NH) Shanghai (PVG) 7 - 7 7/w as of 14/3/30 China Southern Airlines (CZ) Shanghai (PVG) - Guanzhou (CAN) 7 7 7 Air China (CA) Shanghai (PVG) ー Chengdu (CTU) 7 7 7 China Eastern Airlines (MU) Shanghai (PVG) - Xian (XIY) 7 7 7 China Southern Airlines (CZ) Shenyang (SHE) 2 2 2 China Eastern Airlines (MU) Qingdao (TAO) - Beijing (PEK) 7 7 7 Japan Airlines (JL) Tianjin (TSN) 7 7 7 China 10 destinations 81 74 81 China Airlines (CI) Taipei (TPE) 13 11 11 13/w as of 14/3/30 Japan Airlines (JL) Taipei (TPE) 7 7 7 All Nippon Airways (NH) Hong Kong (HKG) 7 7 7 Cathay Pacific Airways (CX) Taipei (TPE) - Hong -

Korean Air – Skypass

Korean Air – Skypass Overview of Reward Availability #8 (total availability is 84%) Economy Reward ranking: City Pairs Queried #6 (total availability is 67%) Business Economy reward. Reward level queried: Business reward. One single reward level is available in economy, business (Prestige), and first class. Summary of reward Reward prices vary by travel season with 251 - 2,500 Miles structure: peak and off-peak levels. (10 total) One way rewards are 50% of the roundtrip price. GMP CJU HKG ICN Airline partners observed Air France, Alitalia, China Eastern, China, Czech, Delta, Garuda Indonesia, KLM, BKK ICN at online booking engine: Vietnam, and Xiamen GMP HND FUK ICN Alliance: SkyTeam Alliance ICN KIX Date queries made: March 2019 ICN NRT Pay with points/miles HAN ICN None offered. (same as cash) PVG ICN SGN ICN Key non-air redemption See note below. opportunities: First market underlined is Search conditions: None selected. intra-Korea; others are international The airline assesses a fuel surcharge for reward travel, but it is not separated from the tax amount. 2,500 + Miles Members may redeem for accommodations (10 total) at 5 hotels (Korea and USA), Seoul airport shuttle, car rental (Jeju only), and airport ICN LAX coat storage. Miles may also be redeemed ICN JFK to pay excess baggage fees and for admission ICN SIN to Korean Air operated lounge locations. ICN SFO Observations: The Family Plan allows up to 5 family CDG ICN members to pool their miles for reward HNL ICN redemption. ATL ICN Members of the Morning Calm Premium ICN LHR Club (top elite tier) qualify for off-peak DPS ICN mileage redemption for award travel during FRA ICN peak season. -

Sky Pearl Club Membership Guide

SKY PEARL CLUB MEMBERSHIP GUIDE Welcome to China Southern Airlines’ Sky Pearl Club The Sky Pearl Club is the frequent flyer program of China Southern Airlines. From the moment you join The Sky Pearl Club, you will experience a whole new world of exciting new travel opportunities with China Southern! Whether you’re traveling for business or pleasure, you’ll be earning mileage toward your award goals every time you fly. Many Elite tier services have been prepared for you. We trust this Guide will soon help you reach your award flight to your dream destinations. China Southern Sky Pearl Club cares about you! 1 A B Earning CZ mileage Redeeming CZ mileage Airlines China Southern Airlines Award Ticket Hotels China Southern Airlines Award Upgrade Banks Partner Airlines Award Ticket Telecommunications, Car Rentals, Business Travel,Dining and others C D Enjoying Sky Pearl Elite Benefits Getting Acquainted with Sky Pearl Rules Definition Membership tiers Membership Qualification and Mileage Account Elite Qualification Mileage Accrual Elite Benefits Mileage Redemption Little Pearl Benefits Membership tier and Elite benefits 2 Others A Earning CZ mileage Whether it’s in the air or on the ground, The Sky Pearl Club gives you more opportunities than ever before to earn Award travel. When flying with China Southern or one of our many airline partners, you can earn FFP mileage. But, that’s not the only way! Hotels stays, car rentals, credit card services, telecommunication services or dining with our business-to-business partners can also help you earn mileage. 3 Airlines Upon making your reservation and ticket booking, please provide your Sky Pearl Club membership number and make sure that passenger’s name and ID is the same as that of your mileage account. -

Delta and Korean Air Create Leading Trans-Pacific Joint Venture

FOR IMMEDIATE DISTRIBUTION CONTACTS: Delta Corporate Communications Korean Air Communications 404-715- 2554 Tel: +7 499 500 73 87 news archive at news.delta.com Delta and Korean Air Create Leading trans-Pacific Joint Venture Airlines to offer customers expanded trans-Pacific network and world-class travel benefits ATLANTA and SEOUL, June 23, 2017 – Delta Air Lines (NYSE:DAL) and Korean Air have reached an agreement to create a leading trans-Pacific joint venture in both scope and service, offering an enhanced and expanded network, industry-leading products and service and a seamless customer experience between the U.S. and Asia. The agreement, signed today, deepens their historic partnership, which spans nearly two decades. “Together, Delta and Korean Air are building a world-class partnership that will offer more destinations, outstanding airport facilities and an unmatched customer experience on the trans-Pacific,” said Ed Bastian, Delta’s CEO. “By combining the strengths of our two companies, we are building a stronger airline for our employees, customers and investors.” “Now is the right time for this JV. The synergies we’re creating will build stronger and more sustainable companies, and this is good for travelers, our companies and our countries,” said Korean Air Chairman, Y.H. Cho. The agreement is the latest expansion of the longstanding partnership between Delta and Korean Air, which began in 2000 when both carriers became co-founders of the SkyTeam global airline alliance. This agreement follows the airlines’ signing of a memorandum of understanding in March announcing the intention to form a joint venture. The joint venture will create a combined network serving more than 290 destinations in the Americas and more than 80 in Asia, providing customers of both airlines with more travel choices than ever before. -

World Air Transport Statistics, Media Kit Edition 2021

Since 1949 + WATSWorld Air Transport Statistics 2021 NOTICE DISCLAIMER. The information contained in this publication is subject to constant review in the light of changing government requirements and regulations. No subscriber or other reader should act on the basis of any such information without referring to applicable laws and regulations and/ or without taking appropriate professional advice. Although every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, the International Air Transport Associ- ation shall not be held responsible for any loss or damage caused by errors, omissions, misprints or misinterpretation of the contents hereof. Fur- thermore, the International Air Transport Asso- ciation expressly disclaims any and all liability to any person or entity, whether a purchaser of this publication or not, in respect of anything done or omitted, and the consequences of anything done or omitted, by any such person or entity in reliance on the contents of this publication. Opinions expressed in advertisements ap- pearing in this publication are the advertiser’s opinions and do not necessarily reflect those of IATA. The mention of specific companies or products in advertisement does not im- ply that they are endorsed or recommended by IATA in preference to others of a similar na- ture which are not mentioned or advertised. © International Air Transport Association. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, recast, reformatted or trans- mitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval sys- tem, without the prior written permission from: Deputy Director General International Air Transport Association 33, Route de l’Aéroport 1215 Geneva 15 Airport Switzerland World Air Transport Statistics, Plus Edition 2021 ISBN 978-92-9264-350-8 © 2021 International Air Transport Association. -

Flying the Overly Friendly Skies: Expanding the Definition of an Accident Under the Warsaw Convention to Include Co-Passenger Sexual Assaults

Volume 46 Issue 2 Article 4 2001 Flying the Overly Friendly Skies: Expanding the Definition of an Accident under the Warsaw Convention to Include Co-Passenger Sexual Assaults Davis L. Wright Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the International Law Commons, Torts Commons, and the Transportation Law Commons Recommended Citation Davis L. Wright, Flying the Overly Friendly Skies: Expanding the Definition of an Accident under the Warsaw Convention to Include Co-Passenger Sexual Assaults, 46 Vill. L. Rev. 453 (2001). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol46/iss2/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Wright: Flying the Overly Friendly Skies: Expanding the Definition of an 2001] FLYING THE OVERLY FRIENDLY SKIES: EXPANDING THE DEFINITION OF AN "ACCIDENT" UNDER THE WARSAW CONVENTION TO INCLUDE CO-PASSENGER SEXUAL ASSAULTS I. INTRODUCTION The aviation industry was still developing in 1929.1 A few brave avia- tors had accomplished the feats of flying from the East Coast to the West Coast of the United States, the first transatlantic and transpacific flights 3 and crossed over both poles. 2 Civil aviation, however, was "in its infancy." In the period between 1925 and 1929, only 400 million passenger miles 4 were flown and the fatality rate was 45 per 100 million passenger miles. Even before these milestones in aviation, members of the interna- tional community set out to create a unified legal system to regulate air 1. -

WAKE ISLAND AIRFIELD, TERMINAL BUILDING HABS UM-2-A (Building 1502) UM-2-A West Side of Wake Avenue Wake Island Us Minor Islands

WAKE ISLAND AIRFIELD, TERMINAL BUILDING HABS UM-2-A (Building 1502) UM-2-A West Side of Wake Avenue Wake Island Us Minor Islands PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY PACIFIC WEST REGIONAL OFFICE National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1111 Jackson Street, Suite 700 Oakland, CA 94607 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY WAKE ISLAND AIRFIELD, TERMINAL BUILDING (Wake Island Airfield, Building 1502) WAKE ISLAND AIRFIELD, TERMINAL BUILDING HABSNo. UM-2-A (Wake Island Airfield, Building 1502) West Side of Wake Avenue Wake Island U.S. Minor Islands Location: The Wake Island Airfield Terminal Building is on the west side of Wake Avenue, east and adjacent to the aircraft parking and fueling apron, and 1,500' north of the east end of the runway on Wake Island of Wake Atoll. It is approximately 1 mile north of Peacock Point. The pedestrian/ street entrance to the terminal is on the east side of the building facing Wake Avenue. The aircraft passenger entrance faces west to the aircraft parking apron and lagoon. Present Owner/ Wake Island is an unorganized, unincorporated territory (possession) of the United Occupant: States, part of the United States Minor Outlying Islands, administered by the Office of Insular Affairs, U.S. Department of the Interior. The airfield terminal is occupied by 15th Air Wing (AW) of the U.S. Air Force (USAF) and base operations support (BOS) services contractor management staff. Present Use: Base operations and air traffic control for USAF, other tenants, and BOS contractor. Significance: The Wake Island airfield played an important and central role in transpacific commercial airline and developments after World War II (WWII). -

Bloomsburg Flying Club Memberships Available! Contact: [email protected]

May 2019 Bloomsburg Municipal Airport BJ Teichman, Airport Coordinator - TOB Dave Ruckle, Pilot [email protected] [email protected] Bloomsburg Flying Club Memberships available! www.flybloomsburg.com Contact: [email protected] Bring a friend who is interested in joining the club! Next Meetings: Sunday 19 May – 6:30 PM - N13 Conference Room Flight Instructors: ▪ Phil Polstra – CFII (Parlor City Flying Club Member / Bloomsburg Flying Club) [email protected] (Independent) 563-552-7670 ▪ Rob Staib – CFII (Independent) [email protected] 570-850-5274 ▪ Hans Lawrence – CFII / MEI / RI (Independent) [email protected] 570-898-8868 ▪ Eric Cipcic, CFI (Independent) ▪ Kody Eyer, CFI (Independent) [email protected] 570-854-5325 N13 Fuel Prices: Currently $4.75/ Gallon, subject to change. Hangar News N13: All hangars are full. – If you wish to be placed on the waiting list, contact [email protected]. 2 Bloomsburg Municipal Airport NEWSLETTER May 2019 N13 Welcomes – “Mouse” and Captain Pelaggi A note of thanks from Jane, foster dog parent. Thank you for all your help yesterday! Mouse has settled into his foster home in Danville with his foster siblings. His pilot Frank, on left, is a volunteer with Pilots and Paws. He flew from Allentown to Long Island to Bloomsburg back to Allentown to make it possible for Mouse to get from his surrendering family to his foster family here. Mouse is my 23rd foster dog from Australian Shepherds Furever. “Mouse” arrives at N13 in style in V-tail Beech Bonanza piloted by Airline Cpt. Pelaggi. Mouse is only 9 months old. He was shipped from Colorado neutered at 10 weeks old and lived his entire 9 months of life in a one- bedroom high-rise apartment with 5 children and 1 adult. -

Fall 2018 Newsletter

TOSHIBA WVMSCA F A L L 2 0 1 8 A Message from Your President S P EC I A L PO I N TS O F INTEREST We love being involved with Sister City friends and activities both here and in Misawa, Japan. We highly recommend that you also consider President’s helping the Japanese delegations have a great visit here, and if possi- Message ble, go to Misawa yourself to experience the incredible Japanese hos- pitality and kindness there. It will be life changing. You’ll gain a new WVMSCA understanding of all the dedication and ANNUAL effort that’s involved on both sides, to MEETING keep the genuine friendships and spe- NOV. 20, 2019 cial experiences fresh and continually 6:30PM AT THE renewed. This is the 37th year for dele- EAST gation visits. These friendly visits and WENATCHEE continuing relationships have made CITY HALL positive impacts on countless people, including multiple generations within Next WVMSCA some families. Board Meeting: Nov. 20, 2018 at David Kelts, President 5:30PM Tears for Sister City Friends, by Jerrilea Crawford Misawa Minute, by John Fair- banks Trivia Quiz Membership Application Old Friends, New Beginnings! New Friends, New Beginnings! P A G E 2 Tears for Sister City Friends By Jerrilea Crawford I’ve attended the farewell dinner for our friends from Misawa a handful of times. The evening is always fun, but a bit tearful as we prepare to say goodbye to our new friends that have been with us for almost a week. However, this year I saw a few more tears after a 16- minute video produced by Charley Voorhis of Vortex Productions.