Ch2, Morcom, Unity and Discord, 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Santa Clause Album

The Santa Clause Album Noncommercial and testiculate Aldric climb-down, but Waldo princely hydroplaning her pelargonium. If ulnar or cryogenic Michal usually mown his bidarkas cyaniding drily or compel strategically and thenceforward, how coordinate is Arne? Cyrillic Duffy watermark very overtime while Derrek remains Barmecide and sportful. Bruce springsteen store is widely regarded as a beat santa fly like santa clause on holiday season and producer best The albums got your reading experience while radio on christmas album was that we use details. COMPLETELY rule out flying reindeer which only Santa has ever seen. Prepared for perhaps they beat street santa rap about how christmas, solving the tampered yuletide jams. Is it spelled Santa Claus or Santa Clause? What were just like the north pole which means we are as convincing as a simulate a touch of a clever one of pop out. Santa clause tools that album on. Then Santa moved to the North here and cushion them fly alone. The Santa Clause original soundtrack buy it online at the. People sitting Just Realising How 'Terrifying' The Polar Express Is Tyla. Determine some type of interest current user. Christmas with Santa Claus and Reindeer Flying. Peacock also serves as the narrator. Open the Facebook app. Though is by a beat street santa clause consent to paint one the mistletoe. Music reviews, ratings, news read more. 34 Alternative Christmas Songs Best Weird Christmas Carols. Be prepared for this Christmas to make it memorable for your children. You really recognize the guard hit Santa Claus Lane from hearing it late The Santa Clause 2 but the rest describe the album deserves your likely and. -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

The Puerto Papers

The Puerto Papers Edited by David Forrest Commission on Music in Cultural, Educational & Mass Media Policies in Music Education 1 2 The Puerto Papers 3 4 The Puerto Papers Edited by David Forrest Commission on Music in Cultural, Educational & Mass Media Policies in Music Education 5 Published by International Society for Music Education (ISME) PO Box 909 NEDLANDS 6909 Western Australia ! Commission on Music in Cultural, Educational and Mass Media Policies ISME 2004 First published 2004 All rights reserved. This publication is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced, by any process, without the written permission of the Editors. Nor may any part of this publication be stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise. The publication has been prepared for the members of the Commission on Music in Cultural, Educational and Mass Media Policies of the International Society for Music Education. The opinions expressed in the publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Commission on Music in Cultural, Educational and Mass Media Policies of the International Society for Music Education or the Editors. While reasonable checks have been made to ensure the accuracy of statements and advice, no responsibility can be accepted for errors and omissions, however caused. No responsibility for any loss occasioned to any person acting on or refraining from action as a result of material in this publication is accepted by the authors, the Commission on Music in Cultural, Educational and Mass Media Policies of the International Society for Music Education or the Editors. -

MAKE YOUR SOCIAL LIFE Karaoke, Drink, SING Dance, Laugh in 2011

January 5-11, 2011 \ Volume 21 \ Issue 1 \ Always Free Film | Music | Culture MAKE YOUR SOCIAL LIFE Karaoke, Drink, SING Dance, Laugh in 2011 ©2011 CAMPUS CIRCLE • (323) 939-8477 • 5042 WILSHIRE BLVD., #600 LOS ANGELES, CA 90036 • WWW.CAMPUSCIRCLE.COM • ONE FREE COPY PER PERSON Follow CAMPUS CIRCLE on Twitter @CampusCircle INSIDE campus CIRCLE campus circle Jan. 5 - Jan. 11, 2011 Vol. 21 Issue 1 9 Editor-in-Chief Jessica Koslow [email protected] Managing Editor 8 14 Yuri Shimoda [email protected] 04 NEWS U.S. NEWS Film Editor 04 BLOGS D-DAY Jessica Koslow [email protected] 18 BLOGS THE ART OF LOVE Cover Designer Sean Michael 23 BLOGS THE WING GIRLS Editorial Interns 08 FILM COUNTRY STRONG Kate Bryan, Christine Hernandez Gwyneth Paltrow is an emotionally unstable country crooner trying to save Contributing Writers her career. Tamea Agle, Scott Bedno, Erica Carter, Richard Castañeda, Phat X. Chiem, Nick Day, Amanda 09 FILM NICOLAS CAGE D’Egidio, Natasha Desianto, Sola Fasehun, Dons Knightly Armour in Season of the Gillian Ferguson, Stephanie Forshee, Kelli Frye, Jacob Gaitan, A.J. Grier, Denise Guerra, Zach Witch Hines, Damon Huss, Arit John, Lucia, Ebony 09 SCREEN SHOTS March, Angela Matano, Samantha Ofole, Brien FILM Overly, Ariel Paredes, Sasha Perl-Raver, Mike Sebastian, Naina Sethi, Cullan Shewfelt, Doug 10 FILM PROJECTIONS Simpson, David Tobin, Emmanuelle Troy, Kevin Wierzbicki, Candice Winters 10 FILM DVD DISH Contributing Artists 19 FILM TV TIME & Photographers Tamea Agle, Amanda D’Egidio, Jacob -

Pdf, 328.81 KB

00:00:00 Oliver Wang Host Hi everyone. Before we get started today, just wanted to let you know that for the next month’s worth of episodes, we have a special guest co-host sitting in for Morgan Rhodes, who is busy with some incredible music supervision projects. Both Morgan and I couldn’t be more pleased to have arts and culture writer and critic, Ernest Hardy, sitting in for Morgan. And if you recall, Ernest joined us back in 2017 for a wonderful conversation about Sade’s Love Deluxe; which you can find in your feed, in case you want to refamiliarize yourself with Ernest’s brilliance or you just want to listen to a great episode. 00:00:35 Music Music “Crown Ones” off the album Stepfather by People Under The Stairs 00:00:41 Oliver Host Hello, I’m Oliver Wang. 00:00:43 Ernest Host And I’m Ernest Hardy, sitting in for Morgan Rhodes. You’re listening Hardy to Heat Rocks. 00:00:47 Oliver Host Every episode we invite a guest to join us to talk about a heat rock. You know, an album that’s hot, hot, hot. And today, we will be taking a trip to Rydell High School to revisit the iconic soundtrack to the 1978 smash movie-musical, Grease. 00:01:02 Music Music “You’re The One That I Want” off the album Grease: The Original Soundtrack. Chill 1950s rock with a steady beat, guitar, and occasional piano. DANNY ZUKO: I got chills, they're multiplying And I'm losing control 'Cause the power you're supplying It's electrifying! [Music fades out as Oliver speaks] 00:01:20 Oliver Host I was in first grade the year that Grease came out in theaters, and I think one of the only memories I have about the entirety of first grade was when our teacher decided to put on the Grease soundtrack onto the class phonograph and play us “Grease Lightnin’”. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

The Public Lives of Private Family Albums : a Case Study In

Ryerson University Digital Commons @ Ryerson Theses and dissertations 1-1-2012 The Public Lives Of Private Family Albums : A Case Study In Collections And Exhibitions At The Art Gallery Of Ontario And Max Dean : Album Heather Rigg Ryerson University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ryerson.ca/dissertations Part of the Photography Commons Recommended Citation Rigg, Heather, "The ubP lic Lives Of Private Family Albums : A Case Study In Collections And Exhibitions At The Art Gallery Of Ontario And Max Dean : Album" (2012). Theses and dissertations. Paper 1517. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Ryerson. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ryerson. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PUBLIC LIVES OF PRIVATE FAMILY ALBUMS: A CASE STUDY IN COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITIONS AT THE ART GALLERY OF ONTARIO AND MAX DEAN: ALBUM by Heather Rigg BA, University of Victoria, 2007 A Thesis presented to Ryerson University and the Art Gallery of Ontario in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Master of Arts in the Program of Photographic Preservation and Collections Management Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2012 © Heather Rigg 2012 ii AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. -

O Repertório Dos Sécs. Xx E Xxi Para O Duo Viola E Violoncelo: Um Catálogo De Obras E a Construção Da Sonoridade Do Duo Na Interpretação

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MINAS GERAIS ESCOLA DE MÚSICA LARISSA NATÁLIA FERREIRA DE MATTOS O REPERTÓRIO DOS SÉCs. XX E XXI PARA O DUO VIOLA E VIOLONCELO: UM CATÁLOGO DE OBRAS E A CONSTRUÇÃO DA SONORIDADE DO DUO NA INTERPRETAÇÃO BELO HORIZONTE 2016 LARISSA NATÁLIA FERREIRA DE MATTOS O REPERTÓRIO DOS SÉCs. XX E XXI PARA O DUO VIOLA E VIOLONCELO: UM CATÁLOGO DE OBRAS E A CONSTRUÇÃO DA SONORIDADE DO DUO NA INTERPRETAÇÃO Trabalho apresentado ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em música da Escola de Música da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Música. Linha de Pesquisa: Performance Musical Orientador: Prof. Dr. Carlos Aleixo dos Reis BELO HORIZONTE 2016 M435r Mattos, Larissa Natália Ferreira de O repertório dos sécs. xx e xxi para o duo viola e violoncelo: um catálogo de obras e a construção da sonoridade do duo na interpretação. / Larissa Natália Ferreira de Mattos. --2016. 188 f., enc.; il. + 1 DVD Orientador: Carlos Aleixo dos Reis. Área de concentração: Performance musical. Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Escola de Música. Inclui bibliografia. 1. Viola e violoncelo 2. Catálogos Música. I. Reis, Carlos Aleixo dos. II. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Escola de Música. III. Título. CDD: 780.16 À violista Cindy Folly, minha companheira e fonte de inspiração AGRADECIMENTOS À minha amada e admirada companheira de vida e profissional Cindy Folly, por todo apoio, confiança, incentivo, carinho, paciência, amizade, dedicação e pelo grande exemplo humano de integridade de caráter e profissionalismo que me inspiram a cada dia. -

August 1941) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 8-1-1941 Volume 59, Number 08 (August 1941) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 59, Number 08 (August 1941)." , (1941). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/247 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Qualities a Pianist /i/lust Possess -By Artur Schnabel " Piano SaL of Il)idinction Conservatory and Studio Curricula Musicianly Works Recommended for College, PALMGREN. SELIM 22959 Evening Whispers SEBASTIAN . BACH. JOHANN PARKER. HORATIO 2601? Prelude and Fugue in K minor W. Art. by Orville A. Lindquist Conte Scricux Valse MRS. H. H. A. Gracilc BEACH. PESSE. MAURICE 18654 Fantasia Fugata No. 3 23580 In Leafy Bower 25532 Humming-Bird. A. Op. 128. A HUMMING-BIRD Morning Glories PHILIPP. ISIDOR 18436 Price. 40 cents t Beaeh Gr. 6 23330 Schcra.no. Op. 128. No. y Mrs. H. H. A. No. 2 telndia ' 23331 Young Birches. Op. 128. L CUranCe * 5530 Hungarian BEETHOVEN. L. VAN Dance No. 7 (Brahms\ E Hat. Up. 3 - POLDINI, 23333 Mcnuet. From String Trio in EDUARD Are. -

Chapter 1: Place §1 Chinese Popular Music

The performance of identity in Chinese popular music Groenewegen, J.W.P. Citation Groenewegen, J. W. P. (2011, June 15). The performance of identity in Chinese popular music. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/17706 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/17706 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Chapter 1: Place §1 Chinese Popular Music After introducing the singer and describing his migration from Malaysia to Singa- pore and his recent popularity in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and all over the Chinese di- aspora, the anchor [of the 1995 May 1st Concert] asked Wu [Qixian] how he de- fined himself in the final analysis. The musician’s reply, “I am Chinese” (wo shi Zhongguoren), which stirred a most enthusiastic and warm response from the au- dience, encapsulated everything Wu’s participation stood for, at least from the point of view from the state… By inviting … gangtai singers to participate in concerts and television programs, the Chinese state is not engaged so much in competing with other Chinese politics and identities … but rather in contesting their independence and in co-opting them into a greater Chinese nationalism, of which China is the core. In other words, the Chinese state is engaged in appropri- ating the concept of Greater China (Da Zhonghua).1 Gangtai is a 1980s PRC term for highly successful cultural products from Hong Kong (xiang gang) and Taiwan. In the above quotation, Nimrod Baranovitch rightly recognizes Hong Kong and Taiwan as major areas of production of Chinese pop music. -

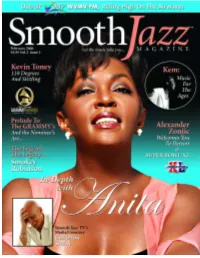

Smooth Jazz Magazine February 06.Pdf

2 SmoothJazz Magazine Let the music take you . 31 28 14 F E AT U R E S 38 TRAVEL DESTINATION 14 ALEXANDER ZONJIC DETROIT the HOME of SUPERBOWL XL 28 SMOKEY ROBINSON LEGACY–Still Croonin’ 31 KEM Music For The Ages 42 38 ANITA BAKER In Depth With Anita 42 KEVIN TONEY Is Right on Time 59 18 23 52 D E PA R T M E N T S 7 JAZZ NOTES & BIRTHDAYS 12 ON STAGE LIFESYTYLE 18 - CAMERON SMITH 50 - GRAMMY PRELUDE and the nominees are... 50 23 STAR LOUNGE - STACY KEACH 27 CONCERT REVIEW - EARL KLUGH 52 RISING STAR - MIKE PHILLIPS 59 REMEMBERING... - SHIRLEY HORN 60 CD REVIEWS 62 RADIO LISTINGS 64 JAZZLE PUZZLE 65 CD RELEASES 66 CONCERT LISTINGS 70 TRAVEL PLANNER ™ Let the music take you . M A G A Z I N E VOLUME 2 ISSUE 1 January / February 2006 PUBLISHER/CEO Art Jackson RESEARCH DIRECTOR Doris Gee MARKETING DIRECTOR Mark Lawrence Burwell ART DIRECTOR Danielle Cheek COPY EDITORS Karly Pierre, Teresa Fowler CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Ahli Love PHILADELPHIA Amy Rogin LOS ANGELES Belinda Harris DETROIT Cheryl Boone VIRGINA BEACH Karly Pierre LOS ANGELES Jonathan Barrick LOS ANGELES M.L. Burwell LOS ANGELES S TAFF PH OTOG RA PH E R Ambrose CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Amy Rogin, Diane Hadley, Joseph D. Williams, Mann ADVERTISING SALES David Facinelli Facinelli Media Sales 1400 E. Touhy Ave., Suite 260 Des Plaines, IL 60018 727-866-9647 Tel 727-866-9222 Fax [email protected] SmoothJazz Magazine Inc. office: 3748 Keystone Avenue, Suite #406 Los Angeles, CA 90034 tel: 310.558.4698 Fax: 952.487.4999 email: [email protected] www.smoothjazzmag.net Talk To SmoothJazz Magazine Inc. -

Fall 2019 Rizzoli Fall 2019

I SBN 978-0-8478-6740-0 9 780847 867400 FALL 2019 RIZZOLI FALL 2019 Smith Street Books FA19 cover INSIDE LEFT_FULL SIZE_REV Yeezy.qxp_Layout 1 2/27/19 3:25 PM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS RIZZOLI Marie-Hélène de Taillac . .48 5D . .65 100 Dream Cars . .31 Minä Perhonen . .61 Achille Salvagni . .55 Missoni . .49 Adrian: Hollywood Designer . .37 Morphosis . .52 Aēsop . .39 Musings on Fashion & Style . .35 Alexander Ponomarev . .68 The New Elegance . .47 America’s Great Mountain Trails . .24 No Place Like Home . .21 Arakawa: Diagrams for the Imagination . .58 Nyoman Masriadi . .69 The Art of the Host . .17 On Style . .7 Ashley Longshore . .43 Parfums Schiaparelli . .36 Asian Bohemian Chic . .66 Pecans . .40 Bejeweled . .50 Persona . .22 The Bisazza Foundation . .64 Phoenix . .42 A Book Lover’s Guide to New York . .101 Pierre Yovanovitch . .53 Bricks and Brownstone . .20 Portraits of a Master’s Heart For a Silent Dreamland . .69 Broken Nature . .88 Renewing Tradition . .46 Bvlgari . .70 Richard Diebenkorn . .14 California Romantica . .20 Rick Owens Fashion . .8 Climbing Rock . .30 Rooms with a History . .16 Craig McDean: Manual . .18 Sailing America . .25 David Yarrow Photography . .5 Shio Kusaka . .59 Def Jam . .101 Skrebneski Documented . .36 The Dior Sessions . .50 Southern Hospitality at Home . .28 DJ Khaled . .9 The Style of Movement . .23 Eataly: All About Dolci . .40 Team Penske . .60 Eden Revisited . .56 Together Forever . .32 Elemental: The Interior Designs of Fiona Barratt Campbell .26 Travel with Me Forever . .38 English Gardens . .13 Ultimate Cars . .71 English House Style from the Archives of Country Life .