Joining the Development of Innovative Pig Farms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Inequality and Institutional Adaptation in Response to Flood Hazards: a Historical Analysis

Copyright © 2018 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. van Bavel, B., D. R. Curtis, and T. Soens. 2018. Economic inequality and institutional adaptation in response to flood hazards: a historical analysis. Ecology and Society 23(4):30. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10491-230430 Research Economic inequality and institutional adaptation in response to flood hazards: a historical analysis Bas van Bavel 1, Daniel R. Curtis 2 and Tim Soens 3 ABSTRACT. To adequately respond to crises, adaptive governance is crucial, but sometimes institutional adaptation is constrained, even when a society is faced with acute hazards. We hypothesize that economic inequality, defined as unequal ownership of wealth and access to resources, crucially interacts with the way institutions function and are adapted or not. Because the time span for societal responses may be lengthy, we use the historical record as a laboratory to test our hypothesis. In doing so, we focus on floods and water management infrastructure. The test area is one where flood hazards were very evident—the Low Countries (present-day Netherlands and Belgium) in the premodern period (1300–1800)—and we employ comparative analysis of three regions within this geographical area. We draw two conclusions: first, both equitable and inequitable societies can demonstrate resilience in the face of floods, but only if the institutions employed to deal with the hazard are suited to the distributive context. Institutions must change parallel to any changes in inequality. Second, we show that institutional adaptation was not inevitable, but also sometimes failed to occur. Institutional adaptation was never inevitably triggered by stimulus of a hazard, but dependent on socio-political context. -

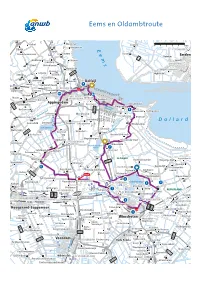

Eems En Oldambtroute

Eems en Oldambtroute Tweehuizen Nieuwstad Kolhol Loquard 0 1 2 3 4 5 km Hoogwatum Zijldijk E e m s 2 PEWSUM Spijk 't Zandstervoorwerk Bierum Rysum Twixlum Emden Godlinze Uiteinde L2 Larrelt Losdorp EMDEN-WEST 't Zandt Oldenklooster Holwierde Logumer Vorwerk Krewerd Lutjerijp Wybelsum Zeerijp Arwerd N997 Nijenklooster Leermens Jukwerd Marsum Delfzijl Eenum Oosterwijtwerd 9 DELFZIJL Loppersum Eekwerd Tjamsweer 10 Wirdum Merum Farmsum Garreweer APPINGEDAM Weiwerd Enzelens Appingedam N360 Garrelsweer Amsweer Geefsweer Zeehaven- Termunterzijl kanaal Borgsweer Hoeksmeer 8 N362 Wartumerklap Termunten Dallingeweer Laskwerd Meedhuizen Wittewierum Eemskanaal Lalleweer Baamsum Opmeeden p ie Dollard ld Steendam ij Overschild Tjuchem Schaapbulten z r Woldendorp te n Schildmeer Zomerdijk u Woltersum Wilderhof rm Geerland Kopaf Te N865 De Paauwen Oostwolderhamrik Wagenborgen Siddeburen Nieuwolda-Oost SIDDEBUREN Luddeweer Nieuwolda Hondshalster- meer 7 Schildwolde Hellum Westeind Denemarken Schaaphok 't Waar OLDAMBT Kostverloren Slochteren Oostwolderpolder Hongerige Wolf Woudbloem Korengarst N362 Oudedijk Ganzedijk 11 Oostwold Airport Finsterwolder- Noordbroek Nieuw Scheemda Oostwold Goldhoorn hamrik Ruiten N387 start Midwolda Finsterwolde Nieuw Beerta Stootshorn 6 Froombosch Noordbroek NOORDBROEK Oldambtmeer 4 Kolham 45 SCHEEMDA 5 Meerland Spitsbergen Uiterburen 1 Ekamp 40 FOXHOL Scheemda REIDERLAND Sappemeer-Noord 43 ZUIDBROEK Beerta terdiep 46 HEILIGERLEE Winscho Blauwestad A7 Hamdijk E22 ZUIDBROEK Ulsda 41 HOOGEZAND 42 SAPPEMEER Zuidbroek 47 WINSCHOTEN -

Gebruikte Literatuur Januari 2009

Bijlage 5: Gebruikte literatuur Januari 2009 Literatuur-/bronnenlijst Toekomstvisie Provincie Groningen Landelijk Programma Landelijk Gebied Groningen Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke (PLG) 2007-2013 Ordening en Milieubeheer (VROM) December 2006 Nota mensen, wensen, wonen; wonen in de 21ste eeuw Provincie Groningen November 2000 Provinciaal Omgevingsplan Groningen (POP) 2009-2013 Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Juni 2009 Ordening en Milieubeheer (VROM) Nota Ruimte: Ruimte voor ontwikkeling Provincie Groningen April 2004 Sociale Agenda 2009-2012 November 2008 Ministerie van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid (SZW) Provincie Groningen Actieprogramma: iedereen doet mee Sportnota Provincie Groningen 2007-2010: Oktober 2007 Mitdoun=Goud Maart 2006 Provinciaal/ regionaal Bureau PAU (i.o.v. Provincie Groningen) Streekraad Oost-Groningen Inventarisatie stedelijke vernieuwingsopgaven Energiek met Energie! in de provincie Groningen (ISV-3) 2010-2019 Maart 2009 April 2008 Stuurgroep Regioprogramma Oost Etin Adviseurs Landschapsontwikkelingsplan Oldambt, Regionaal-economische visie Oost-Groningen Westerwolde en Veenkoloniën (LOP) 2007 Maart 2006 LEADER Actiegroep Oost-Groningen Stuurgroep Regioprogramma Oost LEADER Actieplan 2007-2013 Regioprogramma Oost 2008-2011 29 mei 2007 Juni 2008 Provincie Groningen Oldambt (3 gemeenten gezamenlijk) Actieprogramma Arbeidsmarkt Oost- BügelHajema Adviseurs (i.o.v.Gemeenten Groningen 2008-2013 Reiderland, Scheemda en Winschoten) 2007 Kadernota bestemmingsplan buitengebied Juli 2008 Provincie -

Province House

The Province House SEAT OF PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT Colophon Production and final editing: Province of Groningen Photographs: Alex Wiersma and Jur Bosboom (Province of Groningen), Rien Linthout and Jenne Hoekstra Provincie Groningen Postbus 610 • 9700 AP Groningen +31 (0)50 - 316 41 60 www.provinciegroningen.nl [email protected] 2020 The Province House Seat of Provincial Government PREFACE The present and the past connected with each other. That is how you could describe the Groningen Province House. No. 12 Martinikerkhof is the ‘old’ Province House, which houses the State Hall where the Provincial Council has met since 16 June 1602. That is unique for the Netherlands. No other province has used the same assembly hall for so long. The connection with the present is formed by the aerial bridge to the ‘new’ Province House. This section of the Province House was designed by the architect Mels Crouwel and was opened on 7 May 1996 by Queen Beatrix. Both buildings have their own ambiance, their own history and their own works of art. The painting ‘Religion and Freedom’ by Hermannus Collenius (1650-1723) hangs in the State Hall and paintings by the artistic movement De Ploeg are in the building on the Martinikerkhof. The new section features work by contemporary artists such as Rebecca Horn. Her ‘The ballet of the viewers’ hangs in the hall. The binoculars observe the entrance hall and look out, through the transparent façades, to the outside world. But there is a lot more to see. And this brochure tells you everything about the past and present of the Province House. -

Gemeente Oldambt Bestemmingsplan Finsterwolde, Drieborg, Ganzedijk/Hongerige Wolf

Gemeente Oldambt Bestemmingsplan Finsterwolde, Drieborg, Ganzedijk/Hongerige Wolf Vastgesteld Bestemmingsplan Finsterwolde, Drieborg, Ganzedijk/Hongerige Wolf Code 12-62-04 / 26-06-13 GEMEENTE OLDAMBT 126204 / 26-06-13 BESTEMMINGSPLAN FINSTERWOLDE, DRIEBORG, GANZEDIJK/- HONGERIGE WOLF TOELICHTING INHOUDSOPGAVE blz 1. INLEIDING 1 1. 1. Nieuw bestemmingsplan Finsterwolde, Drieborg, Ganzedijk/Hongerige Wolf 1 1. 2. Wet ruimtelijke ordening-2008 1 1. 3. Plangebied 1 1. 4. Inhoud toelichting 1 2. BELEIDSKADER 2 2. 1. Provinciaal beleid 2 2. 2. Gemeentelijk beleid 3 3. HUIDIGE SITUATIE 5 3. 1. Ruimtelijk-historisch ontstaan en kenmerken 5 3. 2. Cultuurhistorie 8 3. 3. Functionele structuur 10 4. PLANUITGANGSPUNTEN 15 4. 1. De gewenste ruimtelijke structuur 15 4. 2. De gewenste functioneel-ruimtelijke structuur 15 4. 3. Wonen 15 4. 4. Bedrijvigheid 17 4. 5. Voorzieningen en leefbaarheid 18 4. 6. Verkeer 19 4. 7. Groen en recreatie 19 5. OMGEVINGSASPECTEN EN RANDVOORWAARDEN 20 5. 1. Water 20 5. 2. Milieu - geluid 21 5. 3. Bodem 22 5. 4. Externe Veiligheid 22 5. 5. Luchtkwaliteit 24 5. 6. Ecologie 25 5. 7. Cultuurhistorie en archeologie 26 5. 8. Duurzaamheid en energie 27 6. TOELICHTING OP DE BESTEMMINGEN 28 6. 1. Opzet van het bestemmingsplan 28 6. 2. SVBP 2008 28 6. 3. Wet ruimtelijke ordening-2008 / Wabo 2010 28 6. 4. Toelichting op de bestemmingen 29 7. UITVOERBAARHEID 35 7. 1. Maatschappelijke uitvoerbaarheid 35 7. 2. Economische uitvoerbaarheid 35 7. 3. Grondexploitatie 35 8. INSPRAAK EN OVERLEG 36 BIJLAGEN Bijlage 1 Advies Steunpunt Externe veiligheid Bijlage 2 Advies Brandweer Regio Groningen Bijlage 3 Nota inspraak- en overlegreacties 126204 blz 1 1. -

Statistical Yearbook of the Netherlands 2004

Statistical Yearbook of the Netherlands 2004 Statistics Netherlands Preface Statistics Netherlands has a long tradition in the publication of annual figures and yearbooks. The Statistical Yearbook has been the most popular publication by Statistics Netherlands for decades. This latest edition again provides facts and figures on virtually all aspects of Dutch society. It is an invaluable resource for a quick exploration of the economy, population issues, education, health care, crime, culture, the environment, housing, and many other topics. This year’s volume is structured in exactly the same way as last year. It contains the data available at the end of November 2003. For current updates please check the Statline Database at Statistics Netherlands, which is in the process of being translated into English. It can be accessed free of charge at www.cbs.nl. G. van der Veen Director General of Statistics Voorburg / Heerlen, April 2004 Preface Statistical Yearbook 2004 3 Published by Explanation of symbols Statistics Netherlands Prinses Beatrixlaan 428 . = figure not available 2273 XZ Voorburg * = provisional figure The Netherlands x = publication prohibited (confidential figure) Lay out – = nil Statistics Netherlands 0 (0.0) = less than half of unit concerned Facility services department blank = not applicable < = fewer / less / smaller than > = more / greater than Cover design ≤ = fewer / less / smaller than or equal to WAT ontwerpers (Utrecht) ≥ = more / greater than or equal to 2003-2004 = 2003 to 2004 inclusive Print 2003/2004 = average of 2003 up to and Opmeer | De Bink | TDS v.o.f., The Hague including 2004 2003/’04 = crop year, financial year, school Translation year etc. beginning in 2003 and Statistics Netherlands ending in 2004 Rita Gircour Due to rounding, some totals may not correspond with Information the sum of the separate figures E-mail [email protected] How to order Obtainable from The Sdu publishers P.O. -

BELEIDSPLAN Protestantse Gemeente Nieuwolda/Oostwold

BELEIDSPLAN Protestantse Gemeente Nieuwolda/Oostwold/Reiderland 2019-2022 Wie zijn wij Wat doen wij Waar willen wij naar toe Geschiedenis Bestuur van de kerk Gebouwen en financiën Werkgebied Kerkdiensten Toekomst van onze kerk Gebouwen Pastoraat Regionale samenwerking Visie & Missie Commissies & Activiteiten Uitstraling naar buiten Communicatie Wie zijn wij De Protestantse Gemeente van Nieuwolda/Oostwold/Reiderland maakt deel uit van de Protestantse Kerk in Nederland (PKN). Onze gemeente bestaat uit een samenvoeging van de Protestantse gemeente Nieuwolda-Oostwold en de Protestantse Gemeente Reiderland. GESCHIEDENIS De Protestantse Gemeente Nieuwolda/Oostwold bestaat uit een samenvoeging van de Hervormde Kerk Nieuwolda, de Gereformeerde Kerk Nieuwolda en de Protestantse (voorheen Gereformeerde) Kerk van Oostwold. De samenwerking tussen deze kerken is begonnen in 2002 en in 2018 vond de fusie plaats. De Protestantse Gemeente Reiderland is ontstaan uit de Hervormde gemeenten van Finsterwolde, Nieuweschans, Beerta, Nieuw-Beerta/Drieborg en de Gereformeerde kerk van Nieuweschans. Eerste samenwerkingen begonnen al in 1970 en sinds 2000 vormden de genoemde kerken de SOW-gemeente Reiderland. Sinds de landelijke tot stand koming van de PKN in 2004 is het de Protestantse Gemeente Reiderland. De samenwerking tussen de kerken van Nieuwolda/Oostwold en Reiderland gaat jaren terug, in de vorm van gezamenlijke vieringen met Hemelvaart. Ook behoorden de meeste gereformeerden in Finsterwolde in het verleden bij de kerk van Oostwold, waardoor er al goede betrekkingen waren tussen beide plaatsen. In 2016 besloten de kerkenraden van Nieuwolda/Oostwold en Reiderland om vanaf januari 2017 de kerkdiensten samen te houden, waarbij er afwisselend diensten worden gehouden in Oostwold, Nieuwolda, Finsterwolde en Bad Nieuweschans. In 2018 werd besloten tot een fusie, die binnenkort stand komt. -

Holocene Landscape Reconstruction of the Wadden Sea Area Between Marsdiep and Weser

Netherlands Journal of Geosciences — Geologie en Mijnbouw |94 – 2 | 157–183 | 2015 doi:10.1017/njg.2015.4 Holocene landscape reconstruction of the Wadden Sea area between Marsdiep and Weser Explanation of the coastal evolution and visualisation of the landscape development of the northern Netherlands and Niedersachsen in five palaeogeographical maps from 500 BC to present P.C. Vos1,∗ &E.Knol2 1 Deltares, Department of Applied Geology and Geophysics, PO Box 85467, 3508 AL Utrecht, the Netherlands 2 Groninger Museum, PO Box 90, 9700 ME, Groningen, the Netherlands ∗ Corresponding author: Email: [email protected] Manuscript received: 7 August 2014, accepted: 12 January 2015 Abstract This paper describes the background of five palaeogeographical maps between the Marsdiep and the Weser River, and discusses the natural and anthropogenic processes driving the coastal changes during the last part of the Holocene. Before 2500 BC, during the first half of the Holocene, tidal basins were formed in the lower lying Pleistocene valley system as a result of the Holocene sea-level rise. The tidal basins were filled during the second half of the Holocene and on the deposits from the Pleistocene in the hinterland large coastal peat bogs developed. These peat bogs were vulnerable and sensitive to marine ingressions when the peat surface subsided due to drainage, compaction and erosion. During the Subatlantic (450 BC to present), the different ingression systems in the coastal area between Marsdiep and Weser had their own histories in timing and evolution. The ingressions were naturally caused by lateral migration of coastal barrier and tidal-inlet systems or by changes in the natural drainage system in the hinterland. -

GRONINGEN DISCOVERIES GRONINGEN DISCOVERIES GRONINGEN ONTDEK GRONINGEN! DISCOVER GRONINGEN! Groningers Slaan Zichzelf Niet Graag Op De Borst

GRONINGEN DISCOVERIES GRONINGEN DISCOVERIES ONTDEK GRONINGEN! DISCOVER GRONINGEN! Groningers slaan zichzelf niet graag op de borst. We zijn start-up city! Maar liefst een derde van Groningen people are not the type of people to blow We are also a start-up city! No less than a third Ze hebben zelfs een eigen woord voor opscheppen: de ondernemingen uit de Technology Fast 50 van their own trumpet. Or anyone’s trumpet for that of the Deloitte ‘Technology Fast 50’ companies are snakken, en dat is geen aanbeveling. Vinden ze Deloitte komt uit Groningen en omstreken. matter: “Well, it could have been less” is the typical based in or around the city of Groningen. The city iets fantastisch? Dan zeggen de echte Groningers De stad staat op de tweede plaats als het gaat om concise and down to earth way they prefer to put it proudly holds a second place in the list of online gewoon ‘het kon minder’. Het levert prettige mensen online ondernemingen in Nederland. Het grootste when they think something is really absolutely great. companies in the Netherlands. The extensive and in op die graag de handen uit de mouwen steken. en enige Nederlandse natuurlijke Werelderfgoed It makes them nice and modest people, always willing fact only Dutch Natural World Heritage site Die samen veel opbouwen en voor elkaar krijgen. – de Waddenzee en Dark Sky Park Lauwersmeer – to roll up their sleeves and lend a helping hand. – the Wadden Sea and the Lauwersmeer National Die ‘niet lullen maar poetsen’. Maar er schuilt volgens bevinden zich binnen onze provinciegrens! And that’s exactly why they like – and actually are Park (an official Dark Sky Park) – actually lies mij ook een gevaar in. -

Staatscourant 2002, 5, Pag. 25

SZW Rectificatie Abusievelijk is bijlage XIX bij de Regeling SUWI, artikel 7.4, eerste lid, niet gepubliceerd bij de Regeling SUWI zoals deze in de Staatscourant van 3 januari 2002 (nr.2) is verschenen. Deze omis- sie wordt thans hersteld. Bijlage XIX, behorende bij de Regeling SUWI, artikel 7.4, eerste lid Gemeente van vestiging CWI Werkgebied CWI’s Alphen a.d. Rijn Alphen aan den Rijn, Jacobswoude, Liemeer, Nieuwkoop, Rijnwoude, Ter Aar Delft Delft, Nootdorp, Pijnacker, Schipluiden Den Haag (4) ‘s-Gravenhage Gouda Bergambacht, Bodegraven, Boskoop, Gouda, Moordrecht, Nederlek, Nieuwerkerk aan den IJssel, Ouderkerk, Oudewater, Reeuwijk, Schoonhoven, Vlist, Waddinxveen, Zevenhuizen-Moerkapelle Leiden Alkemade, Leiden, Leiderdorp, Oegstgeest, Voorschoten, Zoeterwoude Lisse Hillegom, Katwijk, Lisse, Noordwijk, Noordwijkerhout, Rijnsburg, Sassenheim, Valkenburg, Voorhout, Warmond Naaldwijk De Lier, Maasland, Monster, Naaldwijk, ‘s-Gravenzande, Wateringen Voorburg Leidschendam, Rijswijk, Voorburg, Wassenaar Zoetermeer Zoetermeer Almere Almere, Zeewolde Amersfoort Amersfoort, Bunschoten, Leusden, Woudenberg Hilversum Hilversum, Laren, Loenen, Loosdrecht, Nederhorst den Berg, ‘s-Graveland Huizen Blaricum, Bussum, Huizen, Muiden, Naarden, Weesp Lelystad Lelystad Nieuwegein Houten, IJsselstein, Lopik, Nieuwegein, Vianen Noordoostpolder Dronten, Noordoostpolder, Urk Soest Baarn, Eemnes, Soest Utrecht (3) Breukelen, Maarssen, Montfoort, Utrecht, Woerden Veenendaal Renswoude, Rhenen, Veenendaal Zeist Amerongen, Bunnik, De Bilt, Doorn, Driebergen-Rijsenburg, -

Regionormen En Veranderpercentages Voor Los Land 2019 En 2020

Het gemeenschappelijke secretariaat van de Grondkamers (Secretariaat Juridische Colleges - SJC) is ondergebracht bij RVO.nl. Regionormen en veranderpercentages voor los land 2019 en 2020 Hieronder staan de regionormen en veranderpercentages die gelden vanaf 1 juli 2020 Nieuwe regionorm, oude regionorm en veranderpercentage per pachtprijsgebied voor los bouw- en grasland Pachtovereenkomsten Pachtovereenkomsten op Pachtovereenkomsten op vóór 1 september 2007 of na 1 september 2007 of na 1 september 2007 Regionorm 2020 (€ / Regionorm 2019 (€ / Pachtprijsgebied of regio Veranderpercentage ha) ha) Bouwhoek en Hogeland -1 € 677 € 682 Veenkoloniën en Oldambt -22 € 451 € 581 Noordelijk weidegebied -17 € 535 € 646 Oostelijk veehouderijgebied -13 € 601 € 688 Centraal veehouderijgebied -18 € 448 € 545 IJsselmeerpolders 12 € 1.135 € 1.013 Westelijk Holland -7 € 464 € 501 Waterland en Droogmakerijen -21 € 255 € 324 Hollands Utrechts weidegebied -10 € 714 € 796 Rivierengebied -10 € 660 € 731 Zuidwestelijk akkerbouwgebied 20 € 377 € 315 Zuidwest Brabant -1 € 761 € 768 Zuidelijk veehouderijgebied -16 € 486 € 580 Zuid Limburg -6 € 544 € 576 Nieuwe regionorm, oude regionorm en veranderpercentage per pachtprijsgebied voor los tuinland Pachtovereenkomsten Pachtovereenkomsten op Pachtovereenkomsten op vóór 1 september 2007 of na 1 september 2007 of na 1 september 2007 Veranderpercentage Regionorm 2020 (€ / Regionorm 2019 (€ / Pachtprijsgebied ha) ha) Westelijk Holland (regio 7) 16 € 3.633 € 3.141 Rest van Nederland (overige 9 € 2.646 € 2.431 regio's) Regionale -

People Start Firms?

Against all odds: where do people start firms? Investigating less tangible determinants of new firm formation in the Netherlands Student: Dion (D.Y.) Glastra, BSc. Supervisor: dr. Sierdjan (S.) Koster University of Groningen Faculty of Spatial Sciences Department of Economic Geography Against all odds: where do people start firms? Master’s Thesis Economic Geography Colophon Document title: Against all odds: where do people start firms? Investigating less tangible determinants of new firm formation in the Netherlands Document short title: Against all odds: where do people start firms? Date: January 22nd, 2019 Author: D.Y. (Dion) Glastra, BSc. Student number: S2222140 Contact details: : [email protected] : (00 31) (0)6 55 07 44 13 Document type: Master’s Thesis Status: Final version Study programme: Economic Geography (EG) Educational institute: University of Groningen Faculty of Spatial Sciences Department of Economic Geography Landleven 1 9747 AD Groningen Research supervisor and 1st assessor: dr. S. (Sierdjan) Koster ([email protected]) 2nd assessor: dr. A.J.E. (Arjen) Edzes ([email protected]) Credentials of cover Word cloud (own work, made possible by www.woordwolk.nl) picture: 1 Against all odds: where do people start firms? Master’s Thesis Economic Geography Preface The thesis that is in your hands now, marks the end of the Master Programme in Economic Geography (EG) and, as such, the end of a very exciting, informative and enriching period of my life. This master programme in particular and the entire period of studying at the Faculty of Spatial Sciences and the University of Groningen in general shaped my personality.