The Impact of the Web on the Business Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Link Source

American Historys Greatest Philanthro REATNESS. It’s a surprisingly elusive con - Three basic considerations guided our selection. Gcept. At first it seems intuitive, a superlative First, we focused on personal giving—philanthropy quality so exceptional that it cannot be conducted with one’s own money—rather than insti - missed. But when you try to define greatness, when tutional giving. Second, we only considered the you try to pin down its essence, what once seemed accomplishments attained within the individual’s obvious starts to seem opaque. own lifetime. (For that reason, we did not consider If anything, it’s even living donors, whose harder to describe greatness work is not yet finished.) in philanthropy. When it The Philanthropy Hall of Fame And third, we took a comes to charitable giving, The Roundtable is proud to announce broad view of effective - what separates the good the release of the Philanthropy Hall of ness, acknowledging from the great? Which is that excellence can take Fame, featuring full biographies of more important, the size of many forms. the gift, its percentage of American history’s greatest philan - The results of our net worth, or the return on thropists. Each of the profiles pre - research are inevitably charitable dollar? Is great sented in this article are excerpted subjective. There is a dis - philanthropy necessarily cipline, but not a science, transformative? To what from the Hall of Fame. To read more to the evaluation of great extent is effectiveness a about these seminal figures in Amer - philanthropists. Never - function of the number of ican philanthropy, please visit our new theless, we believe that individuals served, or the website at GreatPhilanthropists.org. -

Create a Legacy of Healing of a Tradition That Symbolizes the ■ Your Assets Will Be Distributed According to Your Wishes

Legacy Giving provides a significant portion of the support NewYork- Presbyterian receives annually. The quality of care, facilities, clinical research, and staff are supported by these gifts. Legacy gifts enable us to provide the finest compassionate health care available, and maintain state-of-the-art facilities for patient care and clinical research. Your legacy benefits our patients, our medical staff, and our community for generations to come. Legacy Giving is Choosing to make a legacy gift offers numerous an act of healing advantages beyond the impact of the gift itself: that continues into ■ You remain fully in control of your assets until the bequest is realized. the future. ■ Unlike some other forms of giving, you may modify To explore the benefits of Gift Planning for you and your family, When you create a legacy at your bequest at anytime during your life. visit our website at: www.nyp.org/give/plannedgiving NewYork-Presbyterian by making a gift through your will ■ Your gift — no matter the amount — can be fully deducted for the purposes of estate taxes. or living trust, you become part Create a Legacy of Healing of a tradition that symbolizes the ■ Your assets will be distributed according to your wishes. spirit on which the hospital was founded: the belief that the health of tomorrow is created today. For additional information, please complete this reply card and return it to the address Benefits of Membership Suggested Bequest Wording below. All responses are confidential. In addition to the gratification afforded by knowing -

Medicine@Yale

hree years after Yale College and he has discovered several new plant Tjoined with the Connecticut species, including species of milkweed Medical Society to establish the and balsamweed, His garden and Medical Institution of Yale College by conservatory at the Medical Institution an Act of the Legislature, thirty-seven are filled with plants that he uses to Students are soon arriving in New-Haven prepare his efficacious Medicines. from all corners of New England to Dr, JONATHAN KNIGHT, who commence studies in Medicine, Anatomy, graduated from Yale College five years Chemistry, and Materia Medica at the ago, studied Medicine in Philadelphia, new school. Seventeen members of the and his practice in Medicine and class come from Connecticut; the rest Surgery is familiar to many in the come from Vermont, New Hampshire, town. Dr. Knight will instruct the new and Massachusetts. Students in Anatomy. The Students, whose names, towns, The cost to the Students for the full and places of residence in New-Haven course of Lectures, described further in are listed here, met the requirement the Advertisement placed on this page for admission, to “produce satisfactory by Dr. Dwight, will be fifty dollars. evidence of a blameless life and The course will last six months, with conversation.” no vacation, and will be given to all The new Medical Institution has thirty-seven Students. During this a most illustrious and accomplished time, the Medical Professors will faculty, assembled by Dr. TIMOTHY perform Surgical Operations, gratis, DWIGHT, the President of Yale College. upon such patients as will consent to Dr. NATHAN SMITH, late of Hanover, be operated upon in presence of the New Hampshire, where he founded the Students of Medicine. -

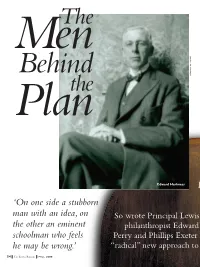

On One Side a Stubborn Man with an Idea, on The

FA06_harkness_10.30.06 10/31/06 9:03 AM Page 24 The Men OF CONGRESS LIBRARY Behind Planthe Edward Harkness ‘On one side a stubborn man with an idea, on So wrote Principal Lewis P the other an eminent philanthropist Edward H schoolman who feels Perry and Phillips Exeter A he may be wrong.’ “radical” new approach to s 24 The Exeter Bulletin fall 2006 FA06_harkness_10.30.06 10/31/06 9:09 AM Page 25 (PERRY AND NOTE):(PERRY PEA ARCHIVES Principal Lewis Perry Their plan revolutionized teaching at Exeter, and s Perry of his close friend, 75 years later continues d Harkness, who challenged to define an Exeter Academy to come up with a education in every way. o secondary school education. Article by Katherine Towler fall 2006 The Exeter Bulletin 25 FA06_harkness_10.30.06 10/31/06 9:15 AM Page 26 PEA ARCHIVES T WAS THE SPRING OF 1930. After months of In the years before the Harkness Exactly who Harkness was research and meetings with faculty,Principal Lewis Perry gift, lives of Exeter students were and why he chose to make traveled to New York to meet with Edward S. Harkness, radically different from those of such a gift is less widely his close friend and one of the country’s leading philan- today. Classes were taught recita- known. It is a remarkable tale thropists. With him, Perry brought an outline of how tion style, with the teacher lectur- involving one of the wealthiest Exeter planned to use a substantial gift Harkness had proposed to people in America in his time, I ing to 25 to 35 students seated make to Phillips Exeter. -

University Mourns Death of Pres. Edward M. Lewis

The Library Reading Roam Copy SPECIAL MEMORIAL SERVICES EDITION i \ T n u ffiam p alrire TUESDAY “ A Live College Newspaper5 Vol. 26. Issue No. 56 UNIVERSITY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE, DURHAM, NEW HAMPSHIRE, MAY 25, 1936 PRICE THREE CENTS Prexy’s Career University Closes Shows Successes All Day Tuesday UNIVERSITY MOURNS DEATH In Many Fields Six Members of 1935-1936 Council Will Act OF PRES. EDWARD M. LEWIS Well Known as Athlete as Bearers Statesman and Educator All University activities will be suspended Tuesday while services are held for the late President Edward M. Relapse Interrupts Born in Machynlleth, North Wales, Lewis. The funeral service will be held on December 25, 1872, President Ed at the Community Church at 11:00 a.m. Expected Recovery (advanced time) followed immediately ward M. Lewis came to this country bjr interment services at the Durham with his parents in 1881. His career has Community Cemetery. News of Death Comes as been wide and varied, including states Students cannot be permitted to at Complete Shock to manship, education, and athletics, and tend the church service because of the in every phase marked with more than small size of the Community Church. All Students Six members of the 1935-36 Student usual success. Council will represent the student body All Durham has been in mourning Athlete as bearers for the President. Graduated from Williams college in They are: past president, David K. since shortly after midnight Sunday 1896, he immediately became prominent Webster; William F. Weir, William V. morning when Dr. Edward Morgan Corcoran, Robert A. -

Translating Homer" by Pe- Translating Homer Ter Jones, in Encounter (Jan

. - THE QUART ER-LY AMERICAN MUSIC BERLIN THE VICTORIANS MOSCOW PIRACY BOOKS PERIODICALS $4.5~ "The SPRING 1988 most auspicious debut in magazine histo y. " An unusual bargain! One Year: $12.00 Two Years: $22.00 Three Years: $30.00 (Add $4.00per year for foreign addresses) Send check, money order, or credit card information (account number, expiration In the second issue date, signature) Visa and Mastercard only Essays and Poetry Fiction please. Patricia Goedicke Ed Minus The Heinz R. Pagels Louis Simpson Deborah Larsen Gettysburg Francis Russell Carol Frost Frederick Busch Review Lewis Perry DanielHoffman TonyArdizzone Gettysburg College Sanford Pinsker Midge Eisele Art Gettysburg, Pennsylvania Gerald Weales Donald Hall 17325 Deborah Tall Edward Koren "His unselfish attitude to life, his exemplary and courageous battle for peace and for reconciliation among the nations, will secure for him a permanent and esteemed place in the memory of our nationu-Konrad Adenauer Frank N. D. Buchman was a small-town American who set out with this audacious vision: "to remake the world." In the process, he stimulated personal and social renewal among hundreds of thousands of men and women all over the world. His astonishing spiritual and moral influence turned up in surprising places-from the formation of Alcoholics Anonymous in the US to the rise of black nationalist independence movements in Africa; from friendships with Thomas Edison and Rudyard Kipling to the lives of great leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi, Jomo Kenyatta, and Harry Truman. Sun Yat-sen said of him: "Buchman is the only man who tells me the truth about myself." Buchman was often the center of controversy, and the organizations he founded- the Oxford Group and later Moral Re-Armament-underwent various investigations. -

Newsletteralumni News of the Newyork-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Department of Surgery Volume 10 Number 2 Fall 2007 Tenth Anniversary Issue

NEWSLETTERAlumni News of the NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Department of Surgery Volume 10 Number 2 Fall 2007 Tenth Anniversary Issue Table of Contents John Jones Surgical Society 177 Fort Washington Avenue, MHB 7SK New York, NY 10032 JJSS at age 10 ..................................................................................................2 Telephone: 212-305-2735 Fax: 212-305-3236 Albert Starr’s Lasker Award .......................................................................3 webpage: www.columbiasurgery.org/alumni/index.html Big (Brick and mortar) Names on Campus ............................................6 Editor: James G. Chandler Where Are They Now? ..............................................................................14 Administrator: Trisha J. Hargaden Design: Columbia University Center for Biomedical Communication JJSS at the ACS Clinical Congress ..........................................................16 The John Jones Surgical Society at Age 10 James G. Chandler The John Jones Surgical Society (JJSS) is alive and well at age Since the AOWSS was a surgical educational society rather 10, holding an annual scientific meeting and dinner on its own in than a Presbyterian Hospital surgical alumni society, most PH grad- the spring and meeting again in the fall at the American College of uates did not notice its demise. Blair Rogers,2 a plastic surgeon who Surgery (ACS). The Society serves as a repository for the icons and had most of his training at Columbia, finishing in 1956, resurrected -

The Commonwealth Fund 2010 Annual Report—Complete

The Commonwealth Fund 2010 Annual Report A Private Foundation Working Toward a High Performance Health System The Commonwealth Fund, among the first private foundations started by a woman philanthropist—Anna M. Harkness—was established in 1918 with the broad charge to enhance the common good. The mission of The Commonwealth Fund is to promote a high performing health care system that achieves better access, improved quality, and greater efficiency, particularly for society's most vulnerable, including low-income people, the uninsured, minority Americans, young children, and elderly adults. The Fund carries out this mandate by supporting independent research on health care issues and making grants to improve health care practice and policy. An international program in health policy is designed to stimulate innovative policies and practices in the United States and other industrialized countries. Cover photo: Dwight Cendrowski ii The Commonwealth Fund 2010 Annual Report Working toward the goal of a high performance health care system for all Americans, the Fund builds on its long tradition of scientific inquiry, a commitment to social progress, partnership with others who share common concerns, and the innovative use of communications to disseminate its work. The 2010 Annual Report offers highlights of the Fund’s activities in the past year. 1 Realizing the Potential of Health Reform The landscape of American health care has changed dramatically since the Affordable Care Act was signed in March 2010. In her essay, President Karen Davis takes readers on a journey through the busy months leading to the passage of this historic law and the first stages of its implementation. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 284 605 JC 870 332 AUTHOR Thoren, Daniel TITLE Reducing Class Size at the Community College

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 284 605 JC 870 332 AUTHOR Thoren, Daniel TITLE Reducing Class Size at the Community College. INSTITUTION Princeton Univ., NJ. Mid-Career Fellowship Program. PUB DATE May 87 NOTE 18p.; One of a series of "Essays by Fellows" on "Policy Issues at the Community College." PUB TYPE Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Classroom Environment; *Class Size; Community Colleges; Learning Strategies; *Program Costs; *School Holding Power; *Small Classes; Student Participation; Teacher Student Relationship; *Teaching Methods; Two Year Colleges; Working Hours ABSTRACT Reducing class size is an important step in promoting effective learning, but reducing a class from 35 to 15 studentsalone will not produce the desired results if faculty do not alter their teaching styles. Students must be empowered through teaching techniques that utilize writing, recitation, reactionpapers, case studies, peer group pressure, small group and individual student responsibility, and peer instruction. The instructor must bea specially trained facilitator rather than a lecturer relyingon tests and textbooks. The General Education curriculum isa logical target for introducing small classes in a community college because these courses seek to develop students' skills in inquiry and communication, and are required of all students. Financinga smaller classes plan would require faculty and administrators toagree to the following conditions: (1) all faculty in the general education curriculum volunteer to participate in the small class -

Footnotes NUMBER 2 VOLUME 33 SUMMER 2008

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY footnotes NUMBER 2 VOLUME 33 SUMMER 2008 INSIDE 2 Conserving rare Library materials 6 Gifted collections expand Library’s scope 10 Walter Netsch, 1920–2008 13 Honor roll of donors NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOARD OF GOVERNORS William A. Gordon, chair Robert D. Avery Suzanne S. Bettman Paul A. Bodine Robert A. Brenner Julie Meyers Brock John S. Burcher Jane A. Burke Thomas R. Butler Jean K. Carton John T. Cunningham IV Gerald E. Egan Harve A. Ferrill John S. Gates Jr. Byron L. Gregory Dwight N. Hopkins James A. Kaduk James R. Lancaster Stephen C. Mack Eloise W. Martin Judith Paine McBrien Howard M. McCue III Peter B. McKee M. Julie McKinley William W. McKittrick Rosemary Powell McLean Marjorie I. Mitchell William C. Mitchell William D. Paden Toni L. Parastie Marie A. Quinlan, life member Mitchell H. Saranow Gordon I. Segal Alan H. Silberman Eric B. Sloan John H. Stassen Stephen M. Strachan Jane Urban Taylor On the cover and back cover Illustrators’ self-portraits and botanical images Nancy McCormick Vella from De historia stirpium commentarii insignes by Leonhart Fuchs, Basel, 1542. Charles Deering Library of Special Collections. Alex Herrera, ex officio Sarah M. Pritchard, ex officio b footnotes SUMMER 2008 NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY footnotes SUMMER 2008, VOLUME 33, NUMBER 2 2 One book at a time The art and craft of conserving the Library’s rare materials 6 The obscure, the quirky, the undervalued Gifted collections expand the scope of University Library 8 Hidden treasures of Northwestern University Library 10 Walter Netsch, 1920–2008 Recipient of the 2008 Deering Family Award 11 Aaron Betsky delivers some “Pragmatic Lessons” Lecture illuminates James Gamble Rogers 12 Endnotes Mandela posters, new Kaplan Fellow 13 Honor roll of donors, 2007 Footnotes is published three times a year by Northwestern University Library. -

Top Ophthalmologists in the Nation

These physicians are among the TOP OPHTHALMOLOGISTS IN THE NATION May is National Healthy Vision Month More than 14 million Americans suffer from uncorrected vision problems such as nearsightedness, farsightedness, astigmatism, and/or presbyopia and can benefit from the use of corrective eyewear such as glasses or contact lenses.The National Eye Institute (NEI) is raising awareness about the importance of eye exams in detecting common — and uncommon — vision problems. Annual eye examinations are also important in diagnosing and treating eye diseases and visual disorders such as diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration, cataracts and other potentially serious conditions. These physicians, whose areas of special expertise include an encompassing range of common and more rare and serious eye and vision disorders, are among the Top Ophthalmologists in the nation as selected by Castle Connolly Medical Ltd. Castle Connolly is the publisher of America’s Top Doctors®, Top Doctors: New York Metro Area, and the source of Top Doctors articles in New York, Inside Jersey, Westchester, Greenwich, Chicago, Seattle, Atlanta, Philadelphia, Boston, Gulf Shore Life, and other magazines throughout the nation. Physicians included in Castle Connolly’s Guides and on its website (www.castleconnolly.com) have been selected based on extensive surveys of physicians nationwide. All physicians who are nominated undergo an extensive review of credentials by Castle Connolly’s physician-led research team. Doctors cannot and do not pay to be selected -

THE WILLIAMS ALUMNI REVIEW Published by the Williams College Alumni Athletic Association

THE WILLIAMS ALUMNI REVIEW Published by the Williams College Alumni Athletic Association TA LC O TT M IN E R BAN K S, Editor and Manager • ....... .................... Issued in February, April, July, October and December of Each Year Annual Subscription $1.00; Single Copies 20 Cents Entered as second class matter February 23, 1909 at the post office at Williamstown, M ass., under the act of March 3 1879. All correspondence should be addressed to the Editor, 61 Main St., Williamstown. VOL. 4 APRIL, 1912 NO. 2 We are glad to call attention to the college student of his day. What a con reproduction in our advertising pages of trast between the motives and circum the etched portrait of Dr. John Bascom stances of a boy of sixty years ago, willing which has lately been issued by a New to endure privation to obtain the learn York publisher. It well represents the ing leading to a chosen calling, and those etching itself, which is a faithful and ad of an easy-going youngster of today, mirable likeness of one of the most emi drifting to college because his friends do, nent of Williams men. “making” a fraternity or a college letter, falling before the requirements of a serious The Williams class of 1885 is doubtless course of study, and drifting off again responsible for the growing custom of without knowing what is coming next! classes with a large membership in and While it would be pretty rough to say about New York holding annual re —as some one did a while ago—that our union dinners in that city.