Scribendi 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Generic Affinities, Posthumanisms and Science-Fictional Imaginings

GENERIC AFFINITIES, POSTHUMANISMS, SCIENCE-FICTIONAL IMAGININGS SPECULATIVE MATTER: GENERIC AFFINITIES, POSTHUMANISMS AND SCIENCE-FICTIONAL IMAGININGS By LAURA M. WIEBE, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Laura Wiebe, October 2012 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2012) Hamilton, Ontario (English and Cultural Studies) TITLE: Speculative Matter: Generic Affinities, Posthumanisms and Science-Fictional Imaginings AUTHOR: Laura Wiebe, B.A. (University of Waterloo), M.A. (Brock University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Anne Savage NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 277 ii ABSTRACT Amidst the technoscientific ubiquity of the contemporary West (or global North), science fiction has come to seem the most current of genres, the narrative form best equipped to comment on and work through the social, political and ethical quandaries of rapid technoscientific development and the ways in which this development challenges conventional understandings of human identity and rationality. By this framing, the continuing popularity of stories about paranormal phenomena and supernatural entities – on mainstream television, or in print genres such as urban fantasy and paranormal romance – may seem to be a regressive reaction against the authority of and experience of living in technoscientific modernity. Nevertheless, the boundaries of science fiction, as with any genre, are relational rather than fixed, and critical engagements with Western/Northern technoscientific knowledge and practice and modern human identity and being may be found not just in science fiction “proper,” or in the scholarly field of science and technology studies, but also in the related genres of fantasy and paranormal romance. -

Scandinavian Studies Newsletter

Department of German, Nordic, and Slavic + Scandinavian Studies Newsletter Fall 2020 Volume xxiv, Issue 1 1 A Message from the Program Chair Greetings to all of you. We sincerely hope that this newsletter finds you well and COVID-free. We also hope that our newsletter will provide you with some interesting reading material now that we’re once again pretty much confined to our homes. Needless to say, this has been a very strange semester for students, staff, and faculty. As you probably know, we started off with smaller classes taught face-to-face, but because of a surge of students testing positive for COVID, we soon had to shift to online teaching. After a couple of weeks, the COVID cases di- minished, and once again faculty and staff teaching low-enrollment classes were allowed back on campus in order to resume face-to-face teaching. Some chose to do so, while others did not. After Thanksgiving, we have all been teaching online. The winter break has been extended by one week, and spring break has been eliminated. This is, of course, an attempt to keep the virus from spreading. We have both good and sad news. We are delighted to welcome two new faculty members: Benjamin Mier- Cruz and Liina-Ly Roos. Both are featured in this newsletter. They bring to the Nordic Unit interesting, new courses and research projects, and we’re very happy to have them as colleagues. The sad news is that Peggy Hager, our lecturer in Norwegian, decided to retire. We’re going to miss her very much. -

TV Finales and the Meaning of Endings Casey J. Mccormick

TV Finales and the Meaning of Endings Casey J. McCormick Department of English McGill University, Montréal A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Casey J. McCormick Table of Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………………….…………. iii Résumé …………………………………………………………………..………..………… v Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………….……...…. vii Chapter One: Introducing Finales ………………………………………….……... 1 Chapter Two: Anticipating Closure in the Planned Finale ……….……… 36 Chapter Three: Binge-Viewing and Netflix Poetics …………………….….. 72 Chapter Four: Resisting Finality through Active Fandom ……………... 116 Chapter Five: Many Worlds, Many Endings ……………………….………… 152 Epilogue: The Dying Leader and the Harbinger of Death ……...………. 195 Bibliography ……………………………………………………………………………... 199 Primary Media Sources ………………………………………………………………. 211 iii Abstract What do we want to feel when we reach the end of a television series? Whether we spend years of our lives tuning in every week, or a few days bingeing through a storyworld, TV finales act as sites of negotiation between the forces of media production and consumption. By tracing a history of finales from the first Golden Age of American television to our contemporary era of complex TV, my project provides the first book- length study of TV finales as a distinct category of narrative media. This dissertation uses finales to understand how tensions between the emotional and economic imperatives of participatory culture complicate our experiences of television. The opening chapter contextualizes TV finales in relation to existing ideas about narrative closure, examines historically significant finales, and describes the ways that TV endings create meaning in popular culture. Chapter two looks at how narrative anticipation motivates audiences to engage communally in paratextual spaces and share processes of closure. -

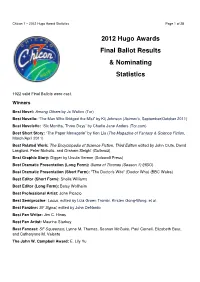

2012 Hugo Awards Final Ballot Results & Nominating Statistics

Chicon 7 – 2012 Hugo Award Statistics Page 1 of 28 2012 Hugo Awards Final Ballot Results & Nominating Statistics 1922 valid Final Ballots were cast. Winners Best Novel: Among Others by Jo Walton (Tor) Best Novella: “The Man Who Bridged the Mist” by Kij Johnson ( Asimov's , September/October 2011) Best Novelette: “Six Months, Three Days” by Charlie Jane Anders (Tor.com) Best Short Story: “The Paper Menagerie” by Ken Liu ( The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction , March/April 2011) Best Related Work: The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Third Edition edited by John Clute, David Langford, Peter Nicholls, and Graham Sleight (Gollancz) Best Graphic Story: Digger by Ursula Vernon (Sofawolf Press) Best Dramatic Presentation (Long Form): Game of Thrones (Season 1) (HBO) Best Dramatic Presentation (Short Form): "The Doctor's Wife" (Doctor Who) (BBC Wales) Best Editor (Short Form): Sheila Williams Best Editor (Long Form): Betsy Wollheim Best Professional Artist: John Picacio Best Semiprozine : Locus, edited by Liza Groen Trombi, Kirsten Gong-Wong, et al. Best Fanzine: SF Signal , edited by John DeNardo Best Fan Writer: Jim C. Hines Best Fan Artist: Maurine Starkey Best Fancast: SF Squeecast , Lynne M. Thomas, Seanan McGuire, Paul Cornell, Elizabeth Bear, and Catherynne M. Valente The John W. Campbell Award: E. Lily Yu Chicon 7 – 2012 Hugo Award Statistics Page 2 of 28 Best Novel – 1664 ballots counted First Place Among Others ( WINNER ) 421 424 493 585 769 Embassytown 324 324 392 492 608 Deadline 311 312 367 418 A Dance With Dragons 316 317 360 -

Liquid Magnets

Liquid Magnets (Activity) Subject Area(s) Material Science, Physics, Chemistry Associated Unit NanoTech Unit or Magnetism Associated Lesson N/A: Associated with Magnetism Activity Title Liquid Magnets Image 1 Grade Level 11-12 (7-12) ADA Description: Magnetic fluid (Ferrofluid) under an induced magnetic Activity Dependency field Caption: Time Required 45-60 minutes (1 full Image file: period) NTUnit_Activity2_Heading.jpg Group Size 3-4 students Source/Rights: Copyright © Justin and Kristina Lapp Expendable Cost per Group US$ http://actualityscience.blogspot.com/201 Variable 0/07/liquid-metal-moving-art.html Summary This activity is designed to introduce to students a unique fluid which its shape can be influenced by magnetic fields. Students will be introduced to concepts of magnetism, surfactants and nanotechnology by relating movie magic (popular culture reference: FRINGE) to practical science. Additionally, students will participate in a fun, engaging activity working with ferrofluids and nanotechnology. This activity serves best to supplement traditional magnetism activities and offer comparisons between large scale materials and nanomaterials. As a fun exercise students will be expected to observe the fluid properties as a stand-alone-fluid and under an imposed magnetic field. Students will understand the components of ferrofluids and there functionality. Also, students will be able to create drawings using magnetically controlled ink out of ferrofluids and create their masterpiece. Engineering Connection Ferrofluids have been around since the 60’s for uses as audio speaker coolants and high end engineering seals. Recently, this technology has been a topic of research involving nano particle suspensions and engineering such materials to have greater magnetic properties under moderate magnetic fields. -

Fringe Series 3 Episode Guide

Fringe series 3 episode guide Continue The apparently haunted building takes several lives. The group tracked down the source as Apartment 6B, in which an elderly woman mourns the loss of her husband. It's a case of ghosts or the beginning of the end of the world. Autonomous history goes well with the main story arc, although it feels artificial and made to do just that. The moments when Peter makes passionate speeches about love that inspire Olivia in their troubled relationship never feel natural and, at best, obvious. In the first days after being kidnapped from another universe, young Peter struggled against his parents and the world that he just knew wasn't his. He then met Olivia Dunham, a young girl who was involved in experiments conducted by a man who called himself his father, and he developed an unlikely relationship. After a few very ordinary episodes, FRINGE bounces back to form with this retro episode set in the 80s and complete with 80s titles, fonts and props. Apeing filming styles of decades goes a little far, since half the long shots don't seem to be in focus, but there's some fun to be had with the period of time. Much more interesting is the fantastical plot that weaves together the mythology of the show to bring the characters together in a way that is both satisfying and entertaining, though it asks the question of how Peter and Olivia could be so significant to each other, and yet never realized that they had met before. -

LECTURE NOTES on Diseases of the Ear, Nose and Throat

Diseases of the Ear, Nose and Throat LECTURE NOTES ON Diseases of the Ear, Nose and Throat P. D. BULL MB, BCh, FRCS Consultant Otolaryngologist Royal Hallamshire Hospital and Sheffield Children’s Hospital Sheffield Honorary Senior Clinical Lecturer in Otolaryngology University of Sheffield Ninth Edition Blackwell Science © 2002 by Blackwell Science Ltd a Blackwell Publishing Company Editorial Offices: Osney Mead, Oxford OX2 0EL, UK Tel: +44 (0)1865 206206 Blackwell Science Inc., 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5018, USA Tel: +1 781 388 8250 Blackwell Science Asia Pty, 54 University Street, Carlton,Victoria 3053, Australia Tel: +61 (0)3 9347 0300 Blackwell Wissenschafts Verlag, Kurfürstendamm 57, 10707 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 (0)30 32 79 060 The right of the Author to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 1961 Reprinted 1988, 1989 Reprinted 1962, 1965, 1967 Seventh edition 1991 Second edition 1968 Reprinted 1992, 1993, 1995 Reprinted 1970, 1971 Four Dragons edition 1991 Third edition 1972 Reprinted 1992, 1995 Reprinted 1975 Eighth edition 1996 Fourth edition 1976 International edition 1996 Reprinted 1978 Reprinted 1999 Fifth edition 1980 Ninth edition 2002 Sixth edition 1985 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bull, P.D. -

Webster's New World Medical Dictionary

01_189283 ffirs.qxp 4/25/08 6:40 PM Page i http://www.rashidislamiccenter.com TM Medical Dictionary Third Edition From the Doctors and Experts at WebMD http://www.allofislam.com/ 01_189283 ffirs.qxp 4/18/08 10:03 PM Page ii http://www.rashidislamiccenter.com Webster’s New World™ Medical Dictionary, Third Edition Copyright © 2008 MedicineNet.com. All rights reserved. Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, (317) 572-3447, fax (317) 572-4355, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. The publisher and the author make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation warranties of fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales or promotional materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for every situation. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional services. -

Season 4 Transcript Bundle

301 - PROLOGUE Liberty Island - Brainwash Session DOCTOR ANDERSON: Agent Dunham, I'm trying to help you get your life back so that you can go home, back to your life, your job, your family. OLIVIA: This is not my home. DOCTOR ANDERSON: Because you come from another universe? OLIVIA: Yes. DOCTOR ANDERSON: Olivia... What is happening to you, given the nature of your job, the upsetting events you come in contact with on a regular basis, coupled with the injury to your head... It's not surprising your mind has created this fantasy... a means of processing the trauma. OLIVIA: This is not a fantasy. DOCTOR ANDERSON: You agree you are an agent with Fringe Division. OLIVIA: I work for the FBI in Fringe Division... dealing with weird and mysterious events that threaten the safety of the United States and its residents. DOCTOR ANDERSON: Good. (picks up a photo and shows it to Olivia) Is this your mother? OLIVIA: She looks like her, but it isn't her. DOCTOR ANDERSON: And these? (shows Olivia two more photos) Agent Lincoln Lee, Charlie Francis... are these your partners? OLIVIA: No. DOCTOR ANDERSON: And who is this? (shows another photo) OLIVIA: Another Olivia Dunham. The Olivia Dunham from over here. DOCTOR ANDERSON: And how does that sound to you, Olivia... What you're saying that there's a world beyond this world populated with people who look exactly like the people here? OLIVIA: It sounds preposterous, which is what I thought when I first learned about it, but as insane as it sounds, it's the truth. -

CONSENT JUDGMENT and PERMANENT INJUNCTION By

Warner Bros Home Entertainment Inc v. Valerie Herrera et al Doc. 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 11 ) 12 Warner Bros. Home Entertainment Inc., ) Case No. CV13-4059 JAK (JCx) ) 13 Plaintiff, ) CONSENT DECREE AND ) PERMANENT INJUNCTION 14 v. ) ) JS-6 15 ) Valerie Herrera a/k/a Valerie Lee, an ) 16 individual and d/b/a as Amazon.com ) Seller Sirena0123, Irvin Y. Lee, an ) 17 individual and d/b/a Amazon.com Seller ) Sirena0123 and Does 2-10, inclusive, ) 18 ) Defendants. ) 19 ) ) 20 21 The Court, having read and considered the Joint Stipulation for Entry of 22 Consent Decree and Permanent Injunction that has been executed by Plaintiff Warner 23 Bros. Home Entertainment Inc. (“Plaintiff”) and Defendants Valerie Herrera a/k/a 24 Valerie Lee, an individual and d/b/a as Amazon.com Seller Sirena0123 and Irvin Y. 25 Lee, an individual and d/b/a Amazon.com Seller Sirena0123 (collectively 26 “Defendants”), in this action, and good cause appearing therefore, hereby: 27 /// 28 /// Warner Bros. v. Herrera: Consent Decree - 1 - Dockets.Justia.com 1 ORDERS that based on the Parties’ stipulation and only as to Defendants, their 2 successors, heirs, and assignees, this Injunction shall be and is hereby entered in the 3 within action as follows: 4 1) This Court has jurisdiction over the parties to this action and over the subject 5 matter hereof pursuant to 17 U.S.C. § 101 et seq., and 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1338. 6 Service of process was properly made against Defendants. -

37Th Annual Central California Research Symposium

37th Annual Central California Research Symposium Proceedings of the 2016 Symposium Convened on Wednesday, April 20, 2016 in the University Business Center California State University, Fresno 37th Annual Central California Research Symposium Sponsoring Institutions California State University, Fresno University of California, San Francisco Fresno Medical Education Program California School of Professional Psychology at Alliant International University Fresno City College American Chemical Society San Joaquin Valley Section Convened in the University Business Center on the campus of California State University, Fresno Wednesday, April 20, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface…………………………………………………………………………………………...i Planning Committee…………………………………………………………………………..ii Letters of Welcome from Sponsoring Institutions California State University, Fresno Dr. Joseph Castro, President…..……………………………………………………………iii University of California, San Francisco Fresno Medical Education Program Dr. Michael Peterson, Associate Dean……………………………………………………iv PROGRAM Concurrent Session A…………………………………………………………………………1 Concurrent Session B………………………………………………………………………….2 Concurrent Session C…………………………………………………………………………3 Concurrent Session D…………………………………………………………………………4 Concurrent Session E………………………………………………………………………….5 Concurrent Session F………………………………………………………………………….6 Plenary Session…………………………………………………………………………………7 Concurrent Session G…………………………………………………………………………8 Concurrent Session H………………………………………………………………………….9 Concurrent Session I…………………………………………………………………………10 Concurrent -

Ke Life, Property Losses Rise LOS ANGELES (AP) - Dents Would Not Be Arrested If Yorty Met with Dr

Area Residents Tell of Quake Ruin SEE STORY BELOW Sunny, Milder Sunny and milder today. Cloudy, TBEMLY mild, showers likely tomorrow. FINAL Cloudy, cold Saturday. ) R*d Btafc, FrethoM 7" (See Details Page 2) I LwgBrmneh / EDITION Monmouth County^ Borne Newspaper for 92. Years VOL. 93 NO. 157 RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 11,1971 30 PAGES TEN CENTS flgj^g^jj^i^ftg^^ ke Life, Property Losses Rise LOS ANGELES (AP) - dents would not be arrested if Yorty met with Dr. Charles that residents stay away until breakfast when the tremor Johnson said he lay pinned' tally demolished," a spokes- restoring water, gas and elec- With the known death toll in they are found in the 20- F. Richter, the. seismologist the reservoir's depth was struck at 6:01 a.m. Tuesday. beneath, wreckage for Pa man said. tric services. Telephone crews the California earthquake at square-mile area of the who perfected the scale which drained to 10 feet, a level ex- hours and "was just about Road Wrecked manned 500 emergency lines 51, Mayor Sam Yorty has ex- sprawling San Fernando Val- measures * an earthquake's pected by Friday afternoon. Ed Johnson, 61, of Baldwin, ready to give up when a man The quake made a wreck of into an area near Van Nor- tended for 48 hours the evacu- ley menaced by the cracking magnitude, and with police Police said permits would La., said he had returned to flashed a light through a hole a Foothill Freeway inter- man Lake where 9,500 phones ation order for 80,000 persons of the dam in the earthquake and fire chiefs and other offi- be required to enter the evac- the hospital the night before and' said, "We'll get you.' " change under construction had been knocked out.