Rinderpest Rinderpest Eradicated Worldwide, As of May 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Late Quaternary Extinction of Ungulates in Sub-Saharan Africa: a Reductionist's Approach

Late Quaternary Extinction of Ungulates in Sub-Saharan Africa: a Reductionist's Approach Joris Peters Ins/itu/ für Palaeoanatomie, Domestikationsforschung und Geschichte der Tiermedizin, Universität München. Feldmochinger Strasse 7, D-80992 München, Germany AchilIes Gautier Laboratorium VDor Pa/eonlo/agie, Seclie Kwartairpaleo1ltologie en Archeozoölogie, Universiteit Gent, Krijgs/aon 2811S8, B-9000 Gent, Belgium James S. Brink National Museum, P. 0. Box 266. Bloemfontein 9300. Republic of South Africa Wim Haenen Instituut voor Gezandheidsecologie, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Capucijnenvoer 35, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium (Received 24 January 1992, revised manuscrip/ accepted 6 November 1992) Comparative osteomorphology and sta ti st ical analysis cf postcranial limb bone measurements cf modern African wildebeest (Collnochaetes), eland (Taura/ragus) and Africa n buffala (Sy" cer"s) have heen applied to reassess the systematic affiliations between these bovids and related extinct Pleistocene forms. The fossil sam pies come from the sites of Elandsfontein (Cape Province) .nd Flarisb.d (Orange Free State) in South Afrie • . On the basis of differenees in skull morphology and size of the appendicular skeleton between fossil and modern blaek wildebeest (ConlJochaeus gnou). the subspecies name anliquus, proposed earlier to designate the Pleistoeene form, ean be retained. The same taxonomie level is accepted for the large Pleistocene e1and, whieh could be named Taurolragus oryx antiquus. The long horned or giant buffa1o, Pelorovis antiquus, can be inc1uded in the polymorphous Syncerus caffer stock and could therefore be called Syncerus caffer antiquus. The ecology of Pleistocene and modern Connochaetes, Taurolragus and Syncerus is discussed. A relationship between herbivore body size and c1imate, as Bergmann's Rule predicts, could not be demonstrated. -

Some Uses of the African Buffalo Syncerus Caffer (Sparrman, 1779) by the Populations Living Around the Comoé National Park (North-East Ivory Coast)

Atta et al., 2021 Journal of Animal & Plant Sciences (J.Anim.Plant Sci. ISSN 2071-7024) Vol.47 (2): 8484-8496 https://doi.org/10.35759/JAnmPlSci.v47-2.6 Some uses of the African buffalo Syncerus caffer (sparrman, 1779) by the populations living around the Comoé National Park (North-East Ivory Coast) ATTA Assemien Cyrille-Joseph 1, SOULEMANE Ouattara 1, KADJO Blaise 1, KOUADIO Yao Roger 2 1 Laboratory of Natural Environment and Biodiversity Conservation, UFR Biosciences, Félix Houphouët-Boigny University, 22 BP 582 Abidjan 22, Côte d’Ivoire 2 Ivorian Office of Parks and Reserves, Côte d’Ivoire, 06 BP 426 Abidjan 06 Correspondance : [email protected] / [email protected] ; Tel : +225 0757311360 Key words: Ethnozoology, Use form, Buffalo, Comoé National Park, Ivory Coast Publication date 28/02/2021, http://m.elewa.org/Journals/about-japs/ 1 ABSTRACT The Comoé National Park (CNP) in Ivory Coast is home to significant biological diversity and is one of the priority areas of the West African protected areas network. It is subject to many anthropic pressures, the most intense in its history have been those of the periods of socio-political crisis that Ivory Coast has experienced. The anthropic pressures which weigh on this park are most often practiced by the riparian populations for their survival. The objective of this study is to list the buffalo's organs and their usual mode of use in order to identify the types of pressure that weigh on the species. It is mainly carried out in twelve villages on the periphery of the Comoé National Park: Bania, Kokpingé, Sanguinari, Mango, Lambira, Kalabo, Banvayo, Kakpin, Amaradougou, Gorowi, Tehini and Saye. -

Rinderpest Frequently Asked Questions

RINDERPEST FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ©FAO/Tony Karumba ©FAO/Tony What is rinderpest? Rinderpest, or cattle plague, is a contagious and highly-fatal disease of cattle, buffaloes, yaks and many other artiodactyls (even-toed un- gulates), both domesticated and wild. Vulnerable animals include swine, giraffes and kudus. Rinderpest is caused by a morbillivirus related to human measles, canine distemper and peste des petits ruminants. What are the clinical signs? Affected animals have a high fever, depression, nasal/ocular dis- charges, erosions in the mouth and the digestive tract, along with diarrhea. The animals rapidly become dehydrated and emaciated, dying one week or so after showing signs of the disease. Does rinderpest Rinderpest is not known to infect humans, but its impact on cattle infect humans? and other animals has had a tremendous impact on human liveli- hoods and food security, due to its ability to wipe out entire herds of cattle in a matter of days. Where did rinderpest come Rinderpest is an ancient disease whose signs were recognized long from and before it bore its current name. The virus could well have been the where did it strike? origin of human measles when people first started to domesticate cattle, more than 10,000 years ago. Historical accounts suggest that rinderpest originated in the steppes of Central Eurasia, later sweep- ing across Europe and Asia with military campaigns and livestock imports. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the disease dev- astated parts of Africa. Rinderpest also appeared briefly in the Amer- icas and Australia with imported animals, but was quickly eliminated. -

Castle Disease, African Swine Fever

Pt. 94 9 CFR Ch. I (1–1–09 Edition) (4) Any water used to transport the 94.17 Dry-cured pork products from regions fish is disposed to a municipal sewage where foot-and-mouth disease, rinder- system that includes waste water dis- pest, African swine fever, classical swine infection sufficient to neutralize any fever, or swine vesicular disease exists. VHS virus or to either a non-dis- 94.18 Restrictions on importation of meat and edible products from ruminants due charging settling pond or a settling to bovine spongiform encephalopathy. pond that disinfects, according to all 94.19 Restrictions on importation from BSE applicable local, State, and Federal minimal-risk regions of meat and edible regulations, sufficiently to neutralize products from ruminants. any VHS virus. 94.20 Gelatin derived from horses or swine, or from ruminants that have not been in PART 94—RINDERPEST, FOOT-AND- any region where bovine spongiform encephalopathy exists. MOUTH DISEASE, FOWL PEST 94.21 [Reserved] (FOWL PLAGUE), EXOTIC NEW- 94.22 Restrictions on importation of beef CASTLE DISEASE, AFRICAN SWINE from Uruguay. FEVER, CLASSICAL SWINE FEVER, 94.23 Importation of poultry meat and other AND BOVINE SPONGIFORM poultry products from Sinaloa and So- nora, Mexico. ENCEPHALOPATHY: PROHIBITED 94.24 Restrictions on the importation of AND RESTRICTED IMPORTATIONS pork, pork products, and swine from the APHIS-defined EU CSF region. Sec. 94.25 Restrictions on the importation of live 94.0 Definitions. swine, pork, or pork products from cer- 94.1 Regions where rinderpest or foot-and- tain regions free of classical swine fever. -

Rinderpestrinderpest

RinderpestRinderpest TexasTexas A&MA&M UniversityUniversity CollegeCollege ofof VeterinaryVeterinary MedicineMedicine Jeffrey Musser, DVM, PhD, DABVP Suzanne Burnham, DVM 2006 Rinderpest SpecialSpecial notenote ofof thanksthanks Many of the excellent images and notes for this presentation are borrowed from these 2 sources From “Rinderpest” a presentation and notes by Dr Moritz van Vuuren, delivered at the Foreign Animal and Emerging Diseases Course, Knoxville, Tenn., 2005 From “Rinderpest” a presentation and notes by Dr Linda Logan delivered to many and diverse audiences including the Colorado Foreign Animal Disease Course of Aug 1-5, 2005, Plum Island Foreign Animal Disease Diagnostics Course and others Rinderpest RinderpestRinderpest RinderpestRinderpest (RP)(RP) isis anan acuteacute oror subacute,subacute, contagiouscontagious viralviral diseasedisease ofof ruminantsruminants andand swine,swine, andand ofof majormajor importanceimportance toto thethe cattlecattle industryindustry Rinderpest RinderpestRinderpest RinderpestRinderpest isis characterizedcharacterized byby highhigh fever,fever, lachrymallachrymal discharge,discharge, inflammation,inflammation, hemorrhage,hemorrhage, necrosis,necrosis, erosionserosions ofof thethe epitheliumepithelium ofof thethe mouthmouth andand ofof thethe digestivedigestive tract,tract, profuseprofuse diarrhea,diarrhea, andand death.death. The “four D’s” of Rinderpest: Depression Diarrhea Dehydration Death Rinderpest RinderpestRinderpest TheThe virusvirus isis relativelyrelatively fragilefragile andand -

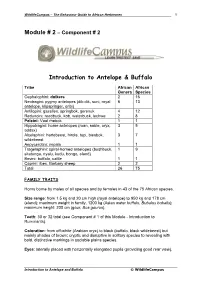

Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo

WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 1 Module # 2 – Component # 2 Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo Tribe African African Genera Species Cephalophini: duikers 2 16 Neotragini: pygmy antelopes (dik-dik, suni, royal 6 13 antelope, klipspringer, oribi) Antilopini: gazelles, springbok, gerenuk 4 12 Reduncini: reedbuck, kob, waterbuck, lechwe 2 8 Peleini: Vaal rhebok 1 1 Hippotragini: horse antelopes (roan, sable, oryx, 3 5 addax) Alcelaphini: hartebeest, hirola, topi, biesbok, 3 7 wildebeest Aepycerotini: impala 1 1 Tragelaphini: spiral-horned antelopes (bushbuck, 1 9 sitatunga, nyalu, kudu, bongo, eland) Bovini: buffalo, cattle 1 1 Caprini: ibex, Barbary sheep 2 2 Total 26 75 FAMILY TRAITS Horns borne by males of all species and by females in 43 of the 75 African species. Size range: from 1.5 kg and 20 cm high (royal antelope) to 950 kg and 178 cm (eland); maximum weight in family, 1200 kg (Asian water buffalo, Bubalus bubalis); maximum height: 200 cm (gaur, Bos gaurus). Teeth: 30 or 32 total (see Component # 1 of this Module - Introduction to Ruminants). Coloration: from off-white (Arabian oryx) to black (buffalo, black wildebeest) but mainly shades of brown; cryptic and disruptive in solitary species to revealing with bold, distinctive markings in sociable plains species. Eyes: laterally placed with horizontally elongated pupils (providing good rear view). Introduction to Antelope and Buffalo © WildlifeCampus WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 2 Scent glands: developed (at least in males) in most species, diffuse or absent in a few (kob, waterbuck, bovines). Mammae: 1 or 2 pairs. Horns. True horns consist of an outer sheath composed mainly of keratin over a bony core of the same shape which grows from the frontal bones. -

Rinderpest Surveillance

XA0301014 INIS-XA--606 Rinderpest Surveillance Rinderpest is probably the most lethal virus disease of cattle and buffalo and can destroy whole populations; damaging economies; undermining food security and ruining the livelihood of farmers and pastoralists. The disease can be eradicated by vaccination and control of livestock movement. The Department of Technical Co-operation is sponsoring a programme, with technical support from the Joint FAO/IAEA Division to provide advice, training and materials to thirteen states through the "Support for Rinderpest Surveillance in West Asia" project. number of livestock vaccinated (sero-sanipling) and lest the serum for antibodies against rinderpest virus. The IAEA Is able to offer procedures and materials for tills purpose through the supply of kits based on the Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) an analogous technique to Radio Irnmuno Assay (R1A). The estimation of the total number of animals in a herd with antibodies gives a measure of the likely protection of the herd produced after vaccination and Is termed sera-monitor Ing. The IAEA also supplies tests which can confirm diagnosis of rinderpest which allows differentiation of other diseases causing similar symptoms. Pasl campaigns have failed to maintain initial successes due lo the absence of monitoring of vaccination and sustaining disease su rve ilia nee . The Model Project Through the Model Project for Support for Rinderpest Surveillance Surveillance IS essential for rinderpest eradication in West Asia, the IAEA Department of Technical Co-operation with the FAO/IAEA Joint Division's Animal Production and Health A dreaded disease Section provides support to the following couniries! Rinderpest epidemics have time and again swept across Europe, Afghan i sign Africa and Asia. -

Incubation Period of Measles from Exposure to Prodrome ■ Exposure to Rash Onset Averages 11 to 12 Days

Measles Paul Gastanaduy, MD; Penina Haber, MPH; Paul A. Rota, PhD; and Manisha Patel, MD, MS Measles is an acute, viral, infectious disease. References to measles can be found from as early as the 7th century. The Measles disease was described by the Persian physician Rhazes in the ● Acute viral infectious disease 10th century as “more to be dreaded than smallpox.” ● First described in 7th century In 1846, Peter Panum described the incubation period of ● Vaccines first licensed include measles and lifelong immunity after recovery from the disease. measles in 1963, MMR in 1971, John Enders and Thomas Chalmers Peebles isolated the virus in and MMRV in 2005 human and monkey kidney tissue culture in 1954. The first live, ● Infection nearly universal attenuated vaccine (Edmonston B strain) was licensed for use in during childhood in the United States in 1963. In 1971, a combined measles, mumps, prevaccine era and rubella (MMR) vaccine was licensed for use in the United ● Still common and often fatal States. In 2005, a combination measles, mumps, rubella, and in developing countries varicella (MMRV) vaccine was licensed. Before a vaccine was available, infection with measles virus was nearly universal during childhood, and more than 90% of persons were immune due to past infection by age 15 years. Measles is still a common and often fatal disease in developing countries. The World Health Organization estimates there were 142,300 deaths from measles globally in 2018. In the United 13 States, there have been recent outbreaks; the largest occurring in 2019 primarily among people who were not vaccinated. -

Nature of the Disease

Manual on the preparation of rinderpest contingency plans 5 Chapter 2 Nature of the disease DEFINITION EPIDEMIOLOGICAL FEATURES Rinderpest, or cattle plague, is an acute, highly Susceptible species contagious viral disease of wild and domesti- Large domestic ruminants. Although all clo- cated ruminants and pigs. It is characterized by ven-hoofed animals are probably susceptible to sudden onset of fever, oculonasal discharges, infection, severe disease occurs most commonly necrotic stomatitis, gastroenteritis and death. in cattle, domesticated water buffaloes and yaks. In a fully susceptible population, as is the Breeds of cattle differ in their clinical response to case in non-endemic areas, morbidity and rinderpest virus. Some breeds have developed a mortality can approach 100 percent. With high innate resistance through selection by long some strains of the virus, however, the dis- association with the disease. ease may be mild with low mortality from Sheep and goats are generally less suscep- infection. tible but may develop clinical disease. Asiatic pigs are susceptible and may suffer WORLD DISTRIBUTION clinical disease. European breeds are less sus- Formerly widespread throughout Europe, Asia ceptible. The latter tend to undergo subclinical and Africa, rinderpest has now been limited to infection and play little or no part in the fairly well-defined locations in South Asia, the maintenance of the disease. Near East and eastern Africa. This has been Camels are apparently not infected and ap- achieved through various national and regional pear to have no role in rinderpest transmission rinderpest eradication programmes. Global and maintenance. rinderpest eradication, which is being targeted for 2010, is being coordinated by FAO. -

Theileria Spp. in Free Ranging Giraffes (Giraffa Camelopardalis) in Zambia

Central Journal of Veterinary Medicine and Research Bringing Excellence in Open Access Case Report *Corresponding author King Shimumbo Nalubamba, Department of Clinical Studies, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Theileria spp. in Free Zambia, P.O. Box 32379, Lusaka, Zambia, Tel: 260 211 293 727; Email: Submitted: 28 November 2015 Ranging Giraffes (Giraffa Accepted: 30 December 2015 Published: 31 December 2015 camelopardalis) in Zambia ISSN: 2378-931X Copyright King Shimumbo Nalubamba1*, Squarre David2, Musso © 2015 Nalubamba et al. Munyeme3, Harvey Kamboyi2, Ngonda Saasa3, Ethel Mkandawire3 OPEN ACCESS and Hetron Mweemba Munang’andu4 1 Department of Clinical Studies, University of Zambia, Zambia Keywords 2 Zambia Wildlife Authority, Zambia • Game ranch 3 Department of Disease Control, University of Zambia, Zambia • Giraffe 4 Department of Basic Sciences and Aquatic Medicine, Norwegian University of Life • Giraffa camelopardalis Sciences, Norway • Piroplasms • Theileria Abstract • Ticks • Wildlife Theileria parasites were detected in five apparently healthy free-ranging giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis Linnaeus, 1758) captured for translocation on a game ranch located approximately 60 km south west of Lusaka. Giemsa-stained blood smears examined under a light microscope showed characteristic oval and rod shaped intra- erythrocytic piroplasms. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products targeted on the 18S rRNA gene showed characteristic bands of Theileria spp. The average number of infected blood cells per field examined by light microscopy was estimated at 48.6% (n=50, SD±8.2%). The mean white blood cell count (WBC), red blood cell count (RBC), haemaglobin and packed cell volume (PCV)(%) for the five giraffes were estimated at 8.0 x 103/µl, 7.9 x 106/µl, 17.8 g/dL and 41.8%, respectively, being within the normal range of hematological values of free-ranging healthy giraffes. -

The Potential Distributions, and Estimated Spatial Requirements And

The potential distributions, and estimated spatial requirements and population sizes, of the medium to large-sized mammals in the planning domain of the Greater Addo Elephant National Park project A.F. BOSHOFF, G.I.H. KERLEY, R.M. COWLING and S.L. WILSON Boshoff, A.F., G.I.H. Kerley, R.M. Cowling and S.L. Wilson. 2002. The potential distri- butions, and estimated spatial requirements and population sizes, of the medium to large-sized mammals in the planning domain of the Greater Addo Elephant National Park project. Koedoe 45(2): 85–116. Pretoria. ISSN 0075-6458. The Greater Addo Elephant National Park project (GAENP) involves the establishment of a mega biodiversity reserve in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Conservation planning in the GAENP planning domain requires systematic information on the potential distri- butions and estimated spatial requirements, and population sizes of the medium to large- sized mammals. The potential distribution of each species is based on a combination of literature survey, a review of their ecological requirements, and consultation with con- servation scientists and managers. Spatial requirements were estimated within 21 Mam- mal Habitat Classes derived from 43 Land Classes delineated by expert-based vegeta- tion and river mapping procedures. These estimates were derived from spreadsheet models based on forage availability estimates and the metabolic requirements of the respective mammal species, and that incorporate modifications of the agriculture-based Large Stock Unit approach. The potential population size of each species was calculat- ed by multiplying its density estimate with the area of suitable habitat. Population sizes were calculated for pristine, or near pristine, habitats alone, and then for these habitats together with potentially restorable habitats for two park planning domain scenarios. -

Peste Des Petits Ruminants Standard Operating Procedures: 1

PESTE DES PETITS RUMINANTS STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES: 1. OVERVIEW OF ETIOLOGY AND ECOLOGY DRAFT NOVEMBER 2013 File name: FAD_Prep_PPR_Eande_Nov2013 SOP number: 1.0 Lead section: Preparedness and Incident Coordination Version number: 2.0 Effective date: November 2013 Review date: November 2016 The Foreign Animal Disease Preparedness and Response Plan (FAD PReP) Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) provide operational guidance for responding to an animal health emergency in the United States. These draft SOPs are under ongoing review. This document was last updated in November 2013. Please send questions or comments to: National Preparedness and Incident Coordination Veterinary Services Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Road, Unit 41 Riverdale, Maryland 20737-1231 Telephone: (301) 851-3595 Fax: (301) 734-7817 E-mail: [email protected] While best efforts have been used in developing and preparing the FAD PReP SOPs, the U.S. Government, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and other parties, such as employees and contractors contributing to this document, neither warrant nor assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information or procedure disclosed. The primary purpose of these FAD PReP SOPs is to provide operational guidance to those government officials responding to a foreign animal disease outbreak. It is only posted for public access as a reference. The FAD PReP SOPs may refer to links to various other Federal and State agencies and private organizations. These links are maintained solely for the user's information and convenience.