Theileria Spp. in Free Ranging Giraffes (Giraffa Camelopardalis) in Zambia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advisory Report: Mammalian Positive List Assessment Framework

Advisory Report: Mammalian Positive List Assessment Framework Scientific Advisory Committee on the Positive List (WAP - Wetenschappelijke Adviescommissie Positieflijst) Maarn, 30 October 2018 Committee members: • Dr Ludo Hellebrekers, chair • Jan Staman, LLM, acting chair • Dr Sietse de Boer • Prof. Ruud Foppen • Dr Marja Kik • Prof. Frans van Knapen • Prof. Jaap Koolhaas • Dennis Lammertsma • Dr Yvonne van Zeeland Wageningen Livestock Research Support: • Geert van der Peet, secretariat and editing • Dr Hans Hopster, research methods 2 Table of Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 1 Assessment framework and risk factors ........................................................................................................ 6 1.1 WAP Working method ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Step-by-step assessment .................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Screening chart ................................................................................................................................. 9 2 Notes and scientific basis ......................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Screening of extremely high risks ...................................................................................................... -

Late Quaternary Extinction of Ungulates in Sub-Saharan Africa: a Reductionist's Approach

Late Quaternary Extinction of Ungulates in Sub-Saharan Africa: a Reductionist's Approach Joris Peters Ins/itu/ für Palaeoanatomie, Domestikationsforschung und Geschichte der Tiermedizin, Universität München. Feldmochinger Strasse 7, D-80992 München, Germany AchilIes Gautier Laboratorium VDor Pa/eonlo/agie, Seclie Kwartairpaleo1ltologie en Archeozoölogie, Universiteit Gent, Krijgs/aon 2811S8, B-9000 Gent, Belgium James S. Brink National Museum, P. 0. Box 266. Bloemfontein 9300. Republic of South Africa Wim Haenen Instituut voor Gezandheidsecologie, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Capucijnenvoer 35, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium (Received 24 January 1992, revised manuscrip/ accepted 6 November 1992) Comparative osteomorphology and sta ti st ical analysis cf postcranial limb bone measurements cf modern African wildebeest (Collnochaetes), eland (Taura/ragus) and Africa n buffala (Sy" cer"s) have heen applied to reassess the systematic affiliations between these bovids and related extinct Pleistocene forms. The fossil sam pies come from the sites of Elandsfontein (Cape Province) .nd Flarisb.d (Orange Free State) in South Afrie • . On the basis of differenees in skull morphology and size of the appendicular skeleton between fossil and modern blaek wildebeest (ConlJochaeus gnou). the subspecies name anliquus, proposed earlier to designate the Pleistoeene form, ean be retained. The same taxonomie level is accepted for the large Pleistocene e1and, whieh could be named Taurolragus oryx antiquus. The long horned or giant buffa1o, Pelorovis antiquus, can be inc1uded in the polymorphous Syncerus caffer stock and could therefore be called Syncerus caffer antiquus. The ecology of Pleistocene and modern Connochaetes, Taurolragus and Syncerus is discussed. A relationship between herbivore body size and c1imate, as Bergmann's Rule predicts, could not be demonstrated. -

Some Uses of the African Buffalo Syncerus Caffer (Sparrman, 1779) by the Populations Living Around the Comoé National Park (North-East Ivory Coast)

Atta et al., 2021 Journal of Animal & Plant Sciences (J.Anim.Plant Sci. ISSN 2071-7024) Vol.47 (2): 8484-8496 https://doi.org/10.35759/JAnmPlSci.v47-2.6 Some uses of the African buffalo Syncerus caffer (sparrman, 1779) by the populations living around the Comoé National Park (North-East Ivory Coast) ATTA Assemien Cyrille-Joseph 1, SOULEMANE Ouattara 1, KADJO Blaise 1, KOUADIO Yao Roger 2 1 Laboratory of Natural Environment and Biodiversity Conservation, UFR Biosciences, Félix Houphouët-Boigny University, 22 BP 582 Abidjan 22, Côte d’Ivoire 2 Ivorian Office of Parks and Reserves, Côte d’Ivoire, 06 BP 426 Abidjan 06 Correspondance : [email protected] / [email protected] ; Tel : +225 0757311360 Key words: Ethnozoology, Use form, Buffalo, Comoé National Park, Ivory Coast Publication date 28/02/2021, http://m.elewa.org/Journals/about-japs/ 1 ABSTRACT The Comoé National Park (CNP) in Ivory Coast is home to significant biological diversity and is one of the priority areas of the West African protected areas network. It is subject to many anthropic pressures, the most intense in its history have been those of the periods of socio-political crisis that Ivory Coast has experienced. The anthropic pressures which weigh on this park are most often practiced by the riparian populations for their survival. The objective of this study is to list the buffalo's organs and their usual mode of use in order to identify the types of pressure that weigh on the species. It is mainly carried out in twelve villages on the periphery of the Comoé National Park: Bania, Kokpingé, Sanguinari, Mango, Lambira, Kalabo, Banvayo, Kakpin, Amaradougou, Gorowi, Tehini and Saye. -

This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached Copy Is Furnished to the Author for Internal Non-Commerci

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/authorsrights Author's personal copy Parasitology International 62 (2013) 448–453 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Parasitology International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/parint Short communication Genotypic variations in field isolates of Theileria species infecting giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis tippelskirchi and Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata) in Kenya Naftaly Githaka a, Satoru Konnai a, Robert Skilton b, Edward Kariuki c, Esther Kanduma b,d, Shiro Murata a, Kazuhiko Ohashi a,⁎ a Department of Disease Control, Graduate School of Veterinary Medicine, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Hokkaido 060-0818, Japan b Biosciences Eastern and Central Africa-International Livestock Research Institute Hub (BecA-ILRI Hub), P.O. Box 30709-00100, Nairobi, Kenya c Kenya Wildlife Service, P.O. Box 40241-00100, Nairobi, Kenya d Department of Biochemistry, University of Nairobi, P.O. Box 30197-00100, Nairobi, Kenya article info abstract Article history: Recently, mortalities among giraffes, attributed to infection with unique species of piroplasms were reported Received 28 January 2013 in South Africa. -

Chapter 15 the Mammals of Angola

Chapter 15 The Mammals of Angola Pedro Beja, Pedro Vaz Pinto, Luís Veríssimo, Elena Bersacola, Ezequiel Fabiano, Jorge M. Palmeirim, Ara Monadjem, Pedro Monterroso, Magdalena S. Svensson, and Peter John Taylor Abstract Scientific investigations on the mammals of Angola started over 150 years ago, but information remains scarce and scattered, with only one recent published account. Here we provide a synthesis of the mammals of Angola based on a thorough survey of primary and grey literature, as well as recent unpublished records. We present a short history of mammal research, and provide brief information on each species known to occur in the country. Particular attention is given to endemic and near endemic species. We also provide a zoogeographic outline and information on the conservation of Angolan mammals. We found confirmed records for 291 native species, most of which from the orders Rodentia (85), Chiroptera (73), Carnivora (39), and Cetartiodactyla (33). There is a large number of endemic and near endemic species, most of which are rodents or bats. The large diversity of species is favoured by the wide P. Beja (*) CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal CEABN-InBio, Centro de Ecologia Aplicada “Professor Baeta Neves”, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] P. Vaz Pinto Fundação Kissama, Luanda, Angola CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Campus de Vairão, Vairão, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] L. Veríssimo Fundação Kissama, Luanda, Angola e-mail: [email protected] E. -

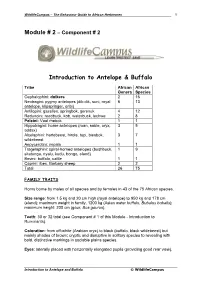

Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo

WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 1 Module # 2 – Component # 2 Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo Tribe African African Genera Species Cephalophini: duikers 2 16 Neotragini: pygmy antelopes (dik-dik, suni, royal 6 13 antelope, klipspringer, oribi) Antilopini: gazelles, springbok, gerenuk 4 12 Reduncini: reedbuck, kob, waterbuck, lechwe 2 8 Peleini: Vaal rhebok 1 1 Hippotragini: horse antelopes (roan, sable, oryx, 3 5 addax) Alcelaphini: hartebeest, hirola, topi, biesbok, 3 7 wildebeest Aepycerotini: impala 1 1 Tragelaphini: spiral-horned antelopes (bushbuck, 1 9 sitatunga, nyalu, kudu, bongo, eland) Bovini: buffalo, cattle 1 1 Caprini: ibex, Barbary sheep 2 2 Total 26 75 FAMILY TRAITS Horns borne by males of all species and by females in 43 of the 75 African species. Size range: from 1.5 kg and 20 cm high (royal antelope) to 950 kg and 178 cm (eland); maximum weight in family, 1200 kg (Asian water buffalo, Bubalus bubalis); maximum height: 200 cm (gaur, Bos gaurus). Teeth: 30 or 32 total (see Component # 1 of this Module - Introduction to Ruminants). Coloration: from off-white (Arabian oryx) to black (buffalo, black wildebeest) but mainly shades of brown; cryptic and disruptive in solitary species to revealing with bold, distinctive markings in sociable plains species. Eyes: laterally placed with horizontally elongated pupils (providing good rear view). Introduction to Antelope and Buffalo © WildlifeCampus WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 2 Scent glands: developed (at least in males) in most species, diffuse or absent in a few (kob, waterbuck, bovines). Mammae: 1 or 2 pairs. Horns. True horns consist of an outer sheath composed mainly of keratin over a bony core of the same shape which grows from the frontal bones. -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

The Potential Distributions, and Estimated Spatial Requirements And

The potential distributions, and estimated spatial requirements and population sizes, of the medium to large-sized mammals in the planning domain of the Greater Addo Elephant National Park project A.F. BOSHOFF, G.I.H. KERLEY, R.M. COWLING and S.L. WILSON Boshoff, A.F., G.I.H. Kerley, R.M. Cowling and S.L. Wilson. 2002. The potential distri- butions, and estimated spatial requirements and population sizes, of the medium to large-sized mammals in the planning domain of the Greater Addo Elephant National Park project. Koedoe 45(2): 85–116. Pretoria. ISSN 0075-6458. The Greater Addo Elephant National Park project (GAENP) involves the establishment of a mega biodiversity reserve in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Conservation planning in the GAENP planning domain requires systematic information on the potential distri- butions and estimated spatial requirements, and population sizes of the medium to large- sized mammals. The potential distribution of each species is based on a combination of literature survey, a review of their ecological requirements, and consultation with con- servation scientists and managers. Spatial requirements were estimated within 21 Mam- mal Habitat Classes derived from 43 Land Classes delineated by expert-based vegeta- tion and river mapping procedures. These estimates were derived from spreadsheet models based on forage availability estimates and the metabolic requirements of the respective mammal species, and that incorporate modifications of the agriculture-based Large Stock Unit approach. The potential population size of each species was calculat- ed by multiplying its density estimate with the area of suitable habitat. Population sizes were calculated for pristine, or near pristine, habitats alone, and then for these habitats together with potentially restorable habitats for two park planning domain scenarios. -

Climate-Change Vulnerabilities and Adaptation Strategies for Africa's

CLIMATE-CHANGE VULNERABILITIES AND ADAPTATION STRATEGIES FOR AFRICA’S CHARISMATIC MEGAFAUNA CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS Jonathan Mawdsley Martha Surridge RESEARCH SUPPORT Bilal Ahmad Sandra Grund Barry Pasco Robert Reeve Chris Robertson ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Deb Callahan Matthew Grason Anne Marsh Ralph and Alice Mawdsley Christine Negra Thomas Nichols Conn Nugent Stacia Van Dyne REVIEWERS Matthew Lewis, WWF Shaun Martin, WWF Dennis Ojima, Colorado State University Robin O’Malley, USGS Wildlife and Climate Change Science Center Karen Terwilliger, Terwilliger Consulting, Inc. Cover photo credit: Martha Surridge CITATION OF THIS REPORT The Heinz Center. 2012. Climate-change Vulnerability and Adaptation Strategies for Africa’s Charismatic Megafauna. Washington, DC, 56 pp. Copyright ©2012 by The H. John Heinz III Center for Science, Economics and the Environment. The H. John Heinz III Center for Science, Economics and the Environment 900 17th St, NW Suite 700 Washington, DC 20006 Phone: (202) 737-6307 Fax: (202) 737-6410 Website: www.heinzctr.org Email: [email protected] Climate-change Vulnerabilities and Adaptation Strategies for Africa’s Charismatic Megafauna TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 Methods 6 Results and Discussion 8 Future Directions 10 Species Profiles The Big Five African Elephant 11 African Lion 13 Cape Buffalo 15 Leopard 17 Rhinoceros, Black 19 Rhinoceros, White 21 African Wild Dog 23 Bongo 25 Cheetah 27 Common Eland 29 Gemsbok 31 Giraffe 33 Greater Kudu 35 Hippopotamus 37 Okapi 39 Wildebeest, Black 41 Wildebeest, Blue 43 Zebra, Grevy’s 45 Zebra, Mountain 47 Zebra, Plains 49 Literature Cited 50 Climate-change Vulnerabilities and Adaptation Strategies for Africa’s Charismatic Megafauna EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The phrase “African animals” brings to mind elephants, lions and other iconic large mammals often referred to as “charismatic megafauna.” The powerful appeal of these animals is demonstrated in the many African wildlife documentaries on television and enduring public support for zoos and museums featuring African animals. -

The U.K. Hunter Who Has Shot More Wildlife Than the Killer of Cecil the Lion

CAMPAIGN TO BAN TROPHY HUNTING Special Report The U.K. hunter who has shot more wildlife than the killer of Cecil the Lion SUMMARY The Campaign to Ban Trophy Hunting is revealing the identity of a British man who has killed wild animals in 5 continents, and is considered to be among the world’s ‘elite’ in the global trophy hunting industry. Malcolm W King has won a staggering 36 top awards with Safari Club International (SCI), and has at least 125 entries in SCI’s Records Book. The combined number of animals required for the awards won by King is 528. Among his awards are prizes for shooting African ‘Big Game’, wild cats, and bears. King has also shot wild sheep, goats, deer and oxen around the world. His exploits have taken him to Asia, Africa and the South Pacific, as well as across Europe. The Campaign to Ban Trophy Hunting estimates that around 1.7 million animals have been killed by trophy hunters over the past decade, of which over 200,000 were endangered species. Lions are among those species that could be pushed to extinction by trophy hunting. An estimated 10,000 lions have been killed by ‘recreational’ hunters in the last decade. Latest estimates for the African lion population put numbers at around 20,000, with some saying they could be as low as 13,000. Industry groups like Safari Club International promote prizes which actively encourage hunters to kill huge numbers of endangered animals. The Campaign to Ban Trophy Hunting believes that trophy hunting is an aberration in a civilised society. -

Temporal and Spatial Dynamics of Gastrointestinal Parasite Infection in Père David’S Deer

Temporal and spatial dynamics of gastrointestinal parasite infection in Père David's deer Shanghua Xu1,*, Shumiao Zhang2,*, Xiaolong Hu3, Baofeng Zhang1, Shuang Yang1, Xin Hu4, Shuqiang Liu1, Defu Hu1 and Jiade Bai2 1 School of Ecology and Nature Conservation, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China 2 Department of Research, Beijing Milu Ecological Research Center, Beijing, China 3 College of Animal Science and Technology, Jiangxi Agricultural University, Nanchang, Jiangxi, China 4 Beijing Key Laboratory of Captive Wildlife Technologies, Beijing Zoo, Beijing, China * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Background. The Père David's deer (Elaphurus davidianus) population was established from only a small number of individuals. Their genetic diversity is therefore relatively low and transmissible (parasitic) diseases affecting them merit further attention. Parasitic infections can affect the health, survival, and population development of the host. However, few reports have been published on the gastrointestinal parasites of Père David's deer. The aims of this study were: (1) to identify the intestinal parasites groups in Père David's deer; (2) to determine their prevalence and burden and clarify the effects of different seasons and regions on various indicators of Père David's deer intestinal parasites; (3) to evaluate the effects of the Père David's deer reproductive period on these parasites; (4) to reveal the regularity of the parasites in space and time. Methods. In total, 1,345 Père David's deer faecal samples from four regions during four seasons were tested using the flotation (saturated sodium nitrate solution) to identify parasites of different genus or group, and the McMaster technique to count the number of eggs or oocysts. -

An Overview of Disease-Free Buffalo Breeding Projects with Reference to the Different Systems Used in South Africa

Sustainability 2012, 4, 3124-3140; doi:10.3390/su4113124 OPEN ACCESS sustainability ISSN 2071-1050 www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability Review An Overview of Disease-Free Buffalo Breeding Projects with Reference to the Different Systems Used in South Africa Liesel Laubscher and Louwrens Hoffman * Department of Animal Science, University of Stellenbosch, Private Bag X1, Matieland 7602, South Africa; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +27-21-808-4747; Fax: +27-21-8084750. Received: 27 August 2012; in revised form: 30 October 2012 / Accepted: 9 November 2012 / Published: 15 November 2012 Abstract: This paper describes the successful national program initiated by the South African government to produce disease-free African buffalo so as to ensure the sustainability of this species due to threats from diseases. Buffalo are known carriers of foot-and-mouth disease, bovine tuberculosis, Corridor disease and brucellosis. A long-term program involving multiphase testing and a breeding scheme for buffalo is described where, after 10 years, a sustainable number of buffalo herds are now available that are free of these four diseases. A large portion of the success was attributable to the use of dairy cows as foster parents with the five-stage quarantine process proving highly effective in maintaining the “disease-free” status of both the calves and the foster cows. The projects proved the successfulness of breeding with African buffalo in a commercial system that was unique to African buffalo and maintained the “wildness” of the animals so that they could effectively be released back into the wild with minimal, if any, behavioral problems.