THE TAMING of the (TRUE) SHREW Maya Tzur Honors Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Taming of the Shrew Teacher Pack 2014

Edited and Directed by Michael Fentiman About this Pack Page 2 The Story Page 2 Q&A with the Director Page 3 Storyboard Page 5 Creating Characters Page 6 The Minola Girls Page 10 The Battle for Bianca Page 11 Creating the World Page 15 Resource Materials Page 18 Registered charity no. 212481 © Royal Shakespeare Company 1 FIRST ENCOUNTER RESOURCES The RSC’s First Encounter series for young audiences aims to give children and young people a vivid, accessible and enjoyable first experience of Shakespeare’s work. These specially edited productions are created to provide a great first introduction to Shakespeare’s plays for new audiences and sow the seeds for a life-long relationship with them. These symbols are used throughout This pack has been designed to support the pack: the RSC’s 2014 First Encounter Production of The Taming of the Shrew, edited and directed by Michael Fentiman. The READ production will tour to schools and Notes from the production, theatres across England and at the Ohio background info or extracts State University in the US. PRACTICAL ACTIVITY An open space activity CLASSROOM ACTIVITY A classroom activity THE STORY LINKS Useful web addresses or research opportunities To discover more about the plot of The Taming of the Shrew you can find a full synopsis of the play on the Royal Shakespeare Company’s website at: http://www.rsc.org.uk/explore/shakespeare/plays/the-taming-of-the-shrew/the- taming-of-the-shrew-synopsis.aspx . If you also look at some of the performance history on those pages, you will see that the range of interpretive possibilities for the play is huge: directors, actors and designers each bring something new and different to their particular production. -

The Taming of the Shrew

DISCOVERY GUIDE 2010 The Taming of the Shrew Directed by Robert Currier Costume Design - Abra Berman Fight Director - Brian Herndon Lighting Design - Larry Krause Properties Design - Joel Eis Set Design - Mark Robinson Stage Manager - Becky Saunders Discovery Guide written by Education Manager Sam Leichter www.marinshakespeare.org Welcome to the Discovery Guide for The Taming of the Shrew! Introduction---------------------------------------------------- Welcome to the theatre! Marin Shakespeare Company is thrilled to present one of the Bard’s greatest comedies, The Taming of the Shrew. Shrew has some of Shakespeare’s most hilarious, wild and witty characters. The story of Petruchio’s efforts to win the hand and heart of Katherine the Curst is full of silliness and wit. For this production, we have set Shakespeare’s classic romantic romp on the high seas! Shakespeare’s broad, whacky characters who populate this story are transported to a Pirates of the Carribean setting. Petruchio, a fortune hunter, becomes a pirate in search of several different kinds of treasure. We hope you enjoy the show! Contents---------------------------------------------------------- PAGE 1 -- Discover: the origins of the play PAGES 2-3 -- Discover: the characters (including actor headshots) PAGES 4-5 -- Discover: the story of the play (or hear a recording at marinshakespeare.org) PAGE 6 -- Discover: major themes in the play PAGES 8-9 -- Discover: classroom connections PAGE 10 -- Discover: discussion questions PAGE 11 -- Discover: key quotes from the play (for discussion or writing topics) PAGE 12 -- Discover: Shakespeare’s insults PAGE 13 -- Discover: additional resources (websites, books and video) A word from the Director--------------------------------- (ON THE COVER: DARREN BRIDGETT AS PETRUCHIO AND CAT THOMPSON AS KATE. -

The Taming of the Shrew 2011 Study Guide

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE’S THE TAMING OF THE SHREW 2011 STUDY GUIDE American Players Theatre PO Box 819 Spring Green, WI www.americanplayers.org THE TAMING OF THE SHREW BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE 2011 STUDY GUIDE Cover Photo: Jonathan Smoots, Tracy Michelle Arnold and James Ridge. All photos by Zane Williams. MANY THANKS! APT would like to thank the following for making our program possible: Dennis & Naomi Bahcall • Tom & Renee Boldt Chuck & Ronnie Jones APT‘s Children‘s Fund at the Madison Community Foundation Community Foundation for the Fox Valley Region, Inc. • Richard & Ethel Herzfeld Foundation IKI Manufacturing, Inc. • Pepsi-Cola Bottling Company • Performing Arts for Youth Sauk County UW-Extension, Arts and Culture Committee Spring Green Arts & Crafts Fair • Dr. Susan Whitworth Tait & Dr. W. Steve Tait AND OUR MAJOR EDUCATION SPONSORS This project was also supported in part by a grant from the Wisconsin Arts Board with funds from the State of Wisconsin. American Players Theatre‘s production of The Taming of the Shrew is part of Shakespeare in American Communities: Shakespeare for a New Generation, sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts in cooperation with Arts Midwest. If you have any questions or comments regarding the exercises or the information within this study guide, please contact Emily Beck, Education Coordinator, at 608-588-7402 x 107, or [email protected]. For more information about APT’s educational programs, please visit our website. www.americanplayers.org Who’s Who in The Taming of the Shrew (From The Essential Shakespeare Handbook) Baptista Minola (John Pribyl) Katherine Minola (Tracy Michelle Arnold) A lord of Padua, he is the father The eponymous shrew, Katherine of the shrewish Kate, and dotes is ―renowned in Padua for her on daughter Bianca. -

The Taming of the Shrew (As Retold by a Bunch of Madmen)

The Taming of the Shrew (as retold by a bunch of madmen) Characters: 1. * Petruchio (Treasure-seeking adventurer, Katherina's husband) (39) 2. * Baptista Minola (Wealthy merchant of Padua) (20) 3. * Katherina (Minola's firey elder daughter) (26) 4. * Gremio (Bianca's elder suitor) (18) 5. * Hortensio (Biancas younger suitor) (26) 6. Lucentio (a young scholar, son of a rich father) (8) 7. Bianca (Minola's gentle younger daughter) (5) 8. Servant #1 (5) 9. Servant #2 (1) 10. Hortensio's Wife (1) 11. Priest (5) 12. Narrator (2) * (Main parts) Scene 1: Crash! Pow! Bam! Doors slammed, glass vases shattered against the fire place, chairs were flung against the wall, or hurled out the window. There were screams of panic and fear and racing footsteps from those trying to get out the way, or those running to stop the uproar. [Pantomime and/or write dialog between Katherina and Bianca] Narrator: It was all just another day in the family home of Baptista Minola, a rich merchant in the beautiful Italian city of Padua. Señor Baptista Minola had two daughters, there was the beautiful, peaceful, sweet-natured younger daughter, Bianca, whom anyone would be delighted to have for a daughter. But then there was Bianca's older sister, Katherina. She had the temper of a wild animal, a shrew in fact. Narrator: Both young women were now old enough to marry. Gentle Bianca had men lining up to marry her. But despite a rumor that their father would pay a lot of money to any man who would marry her, one temper tantrum from Katherina was enough to scare off any man. -

Tough Love Or Domestic Violence?

SO THERE'S THAT… " a phrase said after describing something strange, awkward, ironic, hilarious, crazy, or otherwise profound." -Urban Dic The Taming of the Shrew: Tough Love or Domestic Violence? MAY 24, 2015 / ROSEMARIE KEENE William Shakespeare’s comedy The Taming of the Shrew features the marriage and relationship of Petruchio and Katherine. Although the couple reaches an understanding at the play’s end, the two begin with a bit of a rocky start. To compare their interactions with today’s society, their marriage certainly contains elements of severe domestic abuse. When Petruchio and Katherine meet in Act 2, Scene 1, there is an immediate personality clash (as expected)………..despite a possible immediate attraction for one another. From the beginning, Katherine has been labeled by everyone as “the shrew” with an extremely bad temper. She willingly slaps and verbally abuses people, including her father Baptista Minola and her sister Bianca Minola. Katherine is a bold, intelligent woman who freely speaks her mind in a time when such behavior is quite unacceptable, improper, and unbecoming of a lady of her standing. Page 2 Petruchio, an arrogant and greedy man, arrives in Padua to seek a wife with a large dowry. Once Petruchio learns of Katherine’s large dowry and “availability” for marriage, he desires to have her as his bride. When Baptista informs the suitor that Katherine has an undesirable personality and Petruchio will not receive the twenty thousand crowns until “the special thing is well obtained,/That is, her love, for that is all in all” (Shakespeare 83), Petruchio is determined to “tame” Katherine like one would a hawk. -

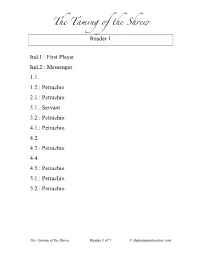

The Taming of the Shrew Reader 1

The Taming of the Shrew Reader 1 Ind.1.: First Player Ind.2.: Messenger 1.1. 1.2.: Petruchio 2.1.: Petruchio 3.1.: Servant 3.2.: Petruchio 4.1.: Petruchio 4.2. 4.3.: Petruchio 4.4. 4.5.: Petruchio 5.1.: Petruchio 5.2.: Petruchio The Taming of the Shrew Reader 1 of 7 © shakespeareteacher.com The Taming of the Shrew Reader 2 Ind.1.: Servingman Ind.2.: Second Servant 1.1.: Lucentio, Katherina Minola 1.2.: Lucentio (disguised as Cambio) 2.1.: Katherina Minola 3.1.: Lucentio (disguised as Cambio) 3.2.: Katherina Minola, Lucentio (disguised as Cambio) 4.1.: Phillip, Katherina Minola 4.2.: Lucentio (disguised as Cambio), Pedant 4.3.: Katherina Minola 4.4.: Pedant (disguised as Vincentio), Lucentio (disguised as Cambio) 4.5.: Katherina Minola 5.1.: Lucentio, Pedant (disguised as Vincentio), Katherina Minola 5.2.: Lucentio, Katherina Minola The Taming of the Shrew Reader 2 of 7 © shakespeareteacher.com The Taming of the Shrew Reader 3 Ind.1.: Lord Ind.2.: Lord (disguised as a servant) 1.1.: Baptista Minola 1.2.: Grumio 2.1.: Baptista Minola 3.1. 3.2.: Baptista Minola, Grumio 4.1.: Grumio 4.2. 4.3.: Grumio 4.4.: Baptista Minola 4.5. 5.1.: Baptista Minola 5.2.: Baptista Minola The Taming of the Shrew Reader 3 of 7 © shakespeareteacher.com The Taming of the Shrew Reader 4 Ind.1.: Second Hunter Ind.2.: First Servant 1.1.: Hortensio, First Servant 1.2.: Hortensio 2.1.: Hortensio (disguised as Licio) 3.1.: Hortensio (disguised as Licio) 3.2. -

Taming of the Shrew for More Information Contact [email protected]

The following pack provides some production background and context as well as providing you with provocations to further consider the production within the wider contemporary context. There are both practical and academic questions within this – please be safe when completing the practical exercises. PRODUCTION CREATIVES Page 3 OVERVIEW and THE PLAY IN PERFORMANCE Page 4 CHARCATER BREAKDOWN Page 6 CONTENT CONTROVERSY Page 7 CONTEXT (Original and Reimagined) Page 8 EXAMINING GENDER IN OTHER SHAKESPEAREAN PRODUCTIONS Page 10 ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CONVENTIONS Page 11 Page 2 of 12 This pack was created by Sherman Theatre for The Taming Of The Shrew For more information contact [email protected] Jo Clifford Jo is a Writer, Performer, Poet & Teacher She was born in North Staffordshire in 1951 and raised as a boy. Aged 7 she was sent to boarding school; during this time (when she was aged 12) her mother suddenly died. She discovered her passion for theatre when she played women’s roles in school plays; where it became clear to her, she was not male. She met her partner, Sue Innes, at St Andrews University in 1971; their partnership lasted 33 years until Sue’s premature death in 2005. In the late eighties Jo wrote a series of major works for the Traverse, with central roles given to women and with gender balanced casts. She is a leading translator from Spanish, French and Portuguese, as well as a radio dramatist, and adapter of novels for radio and the stage. After Sue’s death, she formalised her female identity and began to re-discover herself as actress and performer. -

The Taming of the Shrew 360°

THEATRE FOR A NEW AUDIENCE Milton Glaser THE TAMING OF THE SHREW 360° A VIEWFINDER: Facts and Perspectives on the Play, Playwright, and Production 154 Christopher Street, Suite 3D, New York, NY 10014 • Ph: (212) 229-2819 • F: (212) 229-2911 • www.tfana.org tableTABLE OFOF CONTENTSCONTENTS The Play 3 Synopsis and Characters 4 Sources 7 The Induction 9 Sexual Politics and The Taming of the Shrew 13 Perspectives 16 Selected Performance History The Playwright 18 Biography 19 Timeline of the Life of the Playwright 22 Shakespeare and the American Frontier The Production 24 From the Director 25 Scenic Design 26 Building a Sustainable Set 28 Costume Design 31 Cast and Creative Team Further Exploration 35 Glossary 38 Bibliography About Theatre for a New Audience 40 Mission and Programs 41 Major Institutional Supporters Theatre for a New Audience’s production of The Taming of the Shrew is sponsored by Theatre for a New Audience’s production is part of Shakespeare for a New Generation, a national initiative sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts in cooperation with Arts Midwest. Milton Glaser Notes This Viewfinder will be periodically updated with additional information. Last updated April 2012. Credits Compiled and written by: Carie Donnelson, with contributions from Jonathan Kalb | Edited by: Carie Donnelson and Katie Miller, with assistance from Abigail Unger | Literary Advisor: Jonathan Kalb | Designed by: Milton Glaser, Inc. | Copyright 2012 by Theatre for a New Audience. All rights reserved. With the exception of classroom use by teachers and individual personal use, no part of this study guide may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Kiss Me Kate Cast of Characters Baltimore Cast

KISS ME KATE CAST OF CHARACTERS BALTIMORE CAST SHREW CAST Pops, 60’s, stage doorman, part of quartet for …………… Padua priest, third male solo for Cantiamo Opening Act I and Bianca D’Amore Hattie 30+ Lilli Vanessi’s dresser perhaps ensemble Paul 20’s+ Fred’s dresser, specialty dance, leader perhaps ensemble of solo trio in Too Darn Hot Ralph 30+ Stage manager ensemble singer Lois Lane 25+ Nightclub singer in her first featured Bianca Minola role on the stage Bill Calhoun 25+ a Broadway hoofer, Lois’s partner Lucentio and a chronic gambler Lilli Vanessi, 30’s a star stage and screen actress. Katharine Minola the former wife of Fred Graham Dance Captain 20+ Gregory, servant to Petruchio, ensemble Fred Graham 32 writer, producer, director, actor Petruchio and superman Harry Trevor 50+ a veteran character actor Baptista Minola Stagehand 1 (electrician) and cab driver Nathaniel, servant to Petruchio, second Part of male quartet for Opening Act I and Bianca male solo for Cantiamo D’Amore First Man 30+ a gangster “Aide” to Katharine Second Man 30+ a gangster “Aide” to Katharine Flynt 20’s Aide to General Howell, ensemble dancer Gremio (first suitor) Riley 20’s Aide to General Howell, ensemble dancer Hortensio (second suitor) 1st male solo for 0 Cantiamo D’Amore Stagehand two, 20+ (Assistant electrician) Phillip, servant to Petruchio Part of male quartet for Opening Act 1, Bianca, part of vocal trio in Too Darn Hot Stagehand 3, 20+ ((carpenter) and driver for General Haberdasher Howell. Part of male quartet for Opening Act 1 and Bianca part of vocal trio for Too Darn hot General Harrison Howell 50+ Career military officer, politician, and Lilli’s “new” man Wardrobe Lady, 20+ ensemble part of female quartet for Bianca Ensemble singer Padua Inn waitress Part of female quartet for Bianca Two women 20+ ensemble ensemble part of female quartet for Bianca Additional ensemble Note that age ranges listed may not be the actual age of the actors who are cast. -

Dissertação Luciana Neves Mendes

Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro A REPRESENTAÇÃO DAS PERSONAGENS FEMININAS PRINCIPAIS DE A MEGERA DOMADA DE WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE EM DUAS ADAPTAÇÕES PARA O CINEMA E A TELEVISÃO Luciana Neves Mendes 2011 A REPRESENTAÇÃO DAS PERSONAGENS FEMININAS PRINCIPAIS DE A MEGERA DOMADA DE WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE EM DUAS ADAPTAÇÕES PARA O CINEMA E A TELEVISÃO Luciana Neves Mendes Dissertação apresentada ao Programa Interdisciplinar de Pós-Graduação em Linguística Aplicada, da Faculdade de Letras, da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, como parte dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do título de Mestre em Linguística Aplicada. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Roberto Ferreira da Rocha Rio de Janeiro Setembro de 2011 M538r Mendes, Luciana Neves. A representação das personagens femininas principais de A megera domada de William Shakespeare em duas adaptações para o cinema e a televisão / Luciana Neves Mendes. – Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ, 2011. 203 f. : il. color. ; 30 cm. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Roberto Ferreira da Rocha. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Departamento de Letras Anglo-Germânicas, Programa Interdisciplinar de Linguística Aplicada, Rio de Janeiro, 2011. Bibliografia: f. 194-203. 1. Linguística aplicada. 2. Shakespeare, William (1564- 1616) - A megera domada – Adaptações. 3. Cinema e literatura. 4. Mulheres na literatura. I. Título. II. Rocha, Roberto Ferreira da. CDD 822.33 Ficha elaborada pela Biblioteca José de Alencar – Faculdade de Letras/UFRJ A REPRESENTAÇÃO DAS PERSONAGENS FEMININAS PRINCIPAIS DE A MEGERA DOMADA DE WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE EM DUAS ADAPTAÇÕES PARA O CINEMA E A TELEVISÃO Luciana Neves Mendes Orientador: Prof. Dr. Roberto Ferreira da Rocha Dissertação submetida ao Programa Interdisciplinar de Pós-Graduação em Linguística Aplicada, da Faculdade de Letras, da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, como parte dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do título de Mestre em Linguística Aplicada. -

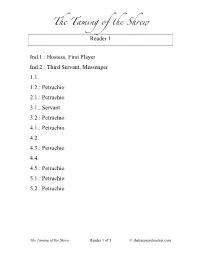

The Taming of the Shrew Reader 1

The Taming of the Shrew Reader 1 Ind.1.: Hostess, First Player Ind.2.: Third Servant, Messenger 1.1. 1.2.: Petruchio 2.1.: Petruchio 3.1.: Servant 3.2.: Petruchio 4.1.: Petruchio 4.2. 4.3.: Petruchio 4.4. 4.5.: Petruchio 5.1.: Petruchio 5.2.: Petruchio The Taming of the Shrew Reader 1 of 5 © shakespeareteacher.com The Taming of the Shrew Reader 2 Ind.1.: First Hunter Ind.2.: First Servant 1.1.: Tranio, Katherina Minola, First Servant 1.2.: Tranio (disguised as Lucentio) 2.1.: Katherina Minola, Tranio (disguised as Lucentio) 3.1. 3.2.: Katherina Minola, Tranio (disguised as Lucentio) 4.1.: Phillip, Nicholas, Katherina Minola 4.2.: Tranio (disguised as Lucentio) 4.3.: Katherina Minola 4.4.: Tranio (disguised as Lucentio) 4.5.: Katherina Minola 5.1.: Tranio (disguised as Lucentio), Katherina Minola 5.2.: Katherina Minola, Tranio The Taming of the Shrew Reader 2 of 5 © shakespeareteacher.com The Taming of the Shrew Reader 3 Ind.1.: Lord Ind.2.: Lord (disguised as a servant) 1.1.: Lucentio, Baptista Minola 1.2.: Grumio, Lucentio (disguised as Cambio) 2.1.: Baptista Minola 3.1.: Lucentio (disguised as Cambio) 3.2.: Baptista Minola, Lucentio (disguised as Cambio), Grumio 4.1.: Grumio 4.2.: Lucentio (disguised as Cambio), Pedant 4.3.: Grumio 4.4.: Pedant (disguised as Vincentio), Baptista Minola, Lucentio (disguised as Cambio) 4.5. 5.1.: Lucentio, Pedant (disguised as Vincentio), Baptista Minola 5.2.: Lucentio, Baptista Minola The Taming of the Shrew Reader 3 of 5 © shakespeareteacher.com The Taming of the Shrew Reader 4 Ind.1.: Christopher Sly, Servingman Ind.2.: Christopher Sly 1.1.: Hortensio, Christopher Sly 1.1.: Hortensio 2.1.: Hortensio (disguised as Licio) 3.1.: Hortensio (disguised as Licio) 3.2. -

The Taming of the Shrew Reader 1

The Taming of the Shrew Reader 1 Ind.1.: Christopher Sly, Second Hunter, Servingman, Second Player Ind.2.: Christopher Sly 1.1.: Gremio, Bianca Minola, Biondello, Christopher Sly 1.2.: Petruchio, Gremio, Biondello 2.1.: Bianca Minola, Gremio, Petruchio 3.1.: Bianca Minola 3.2.: Biondello, Petruchio, Gremio, Bianca Minola 4.1.: Phillip, Petruchio 4.2.: Bianca Minola, Biondello 4.3.: Petruchio 4.4.: Biondello 4.5.: Petruchio 5.1.: Biondello, Gremio, Petruchio, Bianca Minola 5.2.: Petruchio, Gremio, Bianca Minola, Biondello The Taming of the Shrew Reader 1 of 3 © shakespeareteacher.com The Taming of the Shrew Reader 2 Ind.1.: Hostess, First Hunter, First Player Ind.2.: First Servant, Third Servant, Page (disguised as a lady) 1.1.: Tranio, Katherina Minola, Hortensio, First Servant, Page (disguised as a lady) 1.2.: Hortensio, Tranio (disguised as Lucentio) 2.1.: Katherina Minola, Tranio (disguised as Lucentio), Hortensio (disguised as Licio) 3.1.: Hortensio (disguised as Licio) 3.2.: Katherina Minola, Tranio (disguised as Lucentio) 4.1.: Curtis, Nathaniel, Joseph, Katherina Minola, First Servant 4.2.: Tranio (disguised as Lucentio), Hortensio (disguised as Licio) 4.3.: Katherina Minola, Hortensio, Tailor 4.4.: Tranio (disguised as Lucentio) 4.5.: Katherina Minola, Hortensio, Vincentio 5.1: Vincentio, Tranio (disguised as Lucentio), Katherina Minola 5.2.: Hortensio, Katherina Minola, Vincentio, Tranio The Taming of the Shrew Reader 2 of 3 © shakespeareteacher.com The Taming of the Shrew Reader 3 Ind.1.: Lord Ind.2.: Second Servant, Lord (disguised as a servant), Messenger 1.1.: Lucentio, Baptista Minola 1.2.: Grumio, Lucentio (disguised as Cambio) 2.1.: Baptista Minola 3.1.: Lucentio (disguised as Cambio), Servant 3.2.: Baptista Minola, Lucentio (disguised as Cambio), Grumio 4.1.: Grumio, Nicholas, Peter 4.2.: Lucentio (disguised as Cambio), Pedant 4.3.: Grumio, Haberdasher 4.4.: Pedant (disguised as Vincentio), Baptista Minola, Lucentio (disguised as Cambio) 4.5.