Reversed Electron Transport in Syntrophic Degradation of Glucose, Butyrate and Ethanol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core Sulphate-Reducing Microorganisms in Metal-Removing Semi-Passive Biochemical Reactors and the Co-Occurrence of Methanogens

microorganisms Article Core Sulphate-Reducing Microorganisms in Metal-Removing Semi-Passive Biochemical Reactors and the Co-Occurrence of Methanogens Maryam Rezadehbashi and Susan A. Baldwin * Chemical and Biological Engineering, University of British Columbia, 2360 East Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z3, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-604-822-1973 Received: 2 January 2018; Accepted: 17 February 2018; Published: 23 February 2018 Abstract: Biochemical reactors (BCRs) based on the stimulation of sulphate-reducing microorganisms (SRM) are emerging semi-passive remediation technologies for treatment of mine-influenced water. Their successful removal of metals and sulphate has been proven at the pilot-scale, but little is known about the types of SRM that grow in these systems and whether they are diverse or restricted to particular phylogenetic or taxonomic groups. A phylogenetic study of four established pilot-scale BCRs on three different mine sites compared the diversity of SRM growing in them. The mine sites were geographically distant from each other, nevertheless the BCRs selected for similar SRM types. Clostridia SRM related to Desulfosporosinus spp. known to be tolerant to high concentrations of copper were members of the core microbial community. Members of the SRM family Desulfobacteraceae were dominant, particularly those related to Desulfatirhabdium butyrativorans. Methanogens were dominant archaea and possibly were present at higher relative abundances than SRM in some BCRs. Both hydrogenotrophic and acetoclastic types were present. There were no strong negative or positive co-occurrence correlations of methanogen and SRM taxa. Knowing which SRM inhabit successfully operating BCRs allows practitioners to target these phylogenetic groups when selecting inoculum for future operations. -

Fatty Acid Diets: Regulation of Gut Microbiota Composition and Obesity and Its Related Metabolic Dysbiosis

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Fatty Acid Diets: Regulation of Gut Microbiota Composition and Obesity and Its Related Metabolic Dysbiosis David Johane Machate 1, Priscila Silva Figueiredo 2 , Gabriela Marcelino 2 , Rita de Cássia Avellaneda Guimarães 2,*, Priscila Aiko Hiane 2 , Danielle Bogo 2, Verônica Assalin Zorgetto Pinheiro 2, Lincoln Carlos Silva de Oliveira 3 and Arnildo Pott 1 1 Graduate Program in Biotechnology and Biodiversity in the Central-West Region of Brazil, Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande 79079-900, Brazil; [email protected] (D.J.M.); [email protected] (A.P.) 2 Graduate Program in Health and Development in the Central-West Region of Brazil, Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande 79079-900, Brazil; pri.fi[email protected] (P.S.F.); [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (P.A.H.); [email protected] (D.B.); [email protected] (V.A.Z.P.) 3 Chemistry Institute, Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande 79079-900, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-67-3345-7416 Received: 9 March 2020; Accepted: 27 March 2020; Published: 8 June 2020 Abstract: Long-term high-fat dietary intake plays a crucial role in the composition of gut microbiota in animal models and human subjects, which affect directly short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production and host health. This review aims to highlight the interplay of fatty acid (FA) intake and gut microbiota composition and its interaction with hosts in health promotion and obesity prevention and its related metabolic dysbiosis. -

From Sporulation to Intracellular Offspring Production: Evolution

FROM SPORULATION TO INTRACELLULAR OFFSPRING PRODUCTION: EVOLUTION OF THE DEVELOPMENTAL PROGRAM OF EPULOPISCIUM A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by David Alan Miller January 2012 © 2012 David Alan Miller FROM SPORULATION TO INTRACELLULAR OFFSPRING PRODUCTION: EVOLUTION OF THE DEVELOPMENTAL PROGRAM OF EPULOPISCIUM David Alan Miller, Ph. D. Cornell University 2012 Epulopiscium sp. type B is an unusually large intestinal symbiont of the surgeonfish Naso tonganus. Unlike most other bacteria, Epulopiscium sp. type B has never been observed to undergo binary fission. Instead, to reproduce, it forms multiple intracellular offspring. We believe this process is related to endospore formation, an ancient and complex developmental process performed by certain members of the Firmicutes. Endospore formation has been studied for over 50 years and is best characterized in Bacillus subtilis. To study the evolution of endospore formation in the Firmicutes and the relatedness of this process to intracellular offspring formation in Epulopiscium, we have searched for sporulation genes from the B. subtilis model in all of the completed genomes of members of the Firmicutes, in addition to Epulopiscium sp. type B and its closest relative, the spore-forming Cellulosilyticum lentocellum. By determining the presence or absence of spore genes, we see the evolution of endospore formation in closely related bacteria within the Firmicutes and begin to predict if 19 previously characterized non-spore-formers have the genetic capacity to form a spore. We can also map out sporulation-specific mechanisms likely being used by Epulopiscium for offspring formation. -

Assessment of Bacterial Species Present in Pasig River and Marikina River Soil Using 16S Rdna Phylogenetic Analysis

International Journal of Philippine Science and Technology, Vol. 08, No. 2, 2015 !73 SHORT COMMUNICATION Assessment of bacterial species present in Pasig River and Marikina River soil using 16S rDNA phylogenetic analysis Maria Constancia O. Carrillo*, Paul Kenny L. Ko, Arvin S. Marasigan, and Arlou Kristina J. Angeles Department of Physical Sciences and Mathematics, College of Arts and Sciences, University of the Philippines Manila, Padre Faura St., Ermita, Manila Philippines 1000 Abstract—The Pasig River system, which includes its major tributaries, the Marikina, Taguig-Pateros, and San Juan Rivers, is the most important river system in Metro Manila. It is known to be heavily polluted due to the dumping of domestic, industrial and solid wastes. Identification of microbial species present in the riverbed may be used to assess water and soil quality, and can help in assessing the river’s capability of supporting other flora and fauna. In this study, 16S rRNA gene or 16S rDNA sequences obtained from community bacterial DNA extracted from riverbed soil of Napindan (an upstream site along the Pasig River) and Vargas (which is along the Marikina River) were used to obtain a snapshot of the types of bacteria populating these sites. The 16S rDNA sequences of amplicons produced in PCR with total DNA extracted from soil samples as template were used to build clone libraries. Four positive clones were identified from each site and were sequenced. BLAST analysis revealed that none of the contiguous sequences obtained had complete sequence similarity to any known cultured bacterial species. Using the classification output of the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) Classifier and DECIPHER programs, 16S rDNA sequences of closely related species were collated and used to construct a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree using MEGA6. -

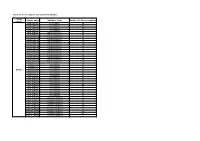

Table S1: List of Samples Included in the Analysis

Table S1: list of samples included in the analysis Study Sample name Inhibitory status Number of days at sampling number DNA.0P2T4 No inhibition 29 DNA.0P2T6 No inhibition 57 DNA.10P2T4 No inhibition 29 DNA.10P2T6 No inhibition 57 DNA.75P2T4 Phenol inhibition 29 DNA.75P2T6 Phenol inhibition 57 DNA.100P2T4 Phenol inhibition 29 DNA.100P2T6 Phenol inhibition 57 DNA.125P1T4 Phenol inhibition 29 DNA.125P1T6 Phenol inhibition 57 DNA.125P2T4 Phenol inhibition 29 DNA.125P2T6 Phenol inhibition 57 DNA.125P3T4 Phenol inhibition 29 DNA.125P3T6 Phenol inhibition 57 DNA.150P2T4 Phenol inhibition 29 DNA.150P2T6 Phenol inhibition 57 DNA.200P2T4 Phenol inhibition 29 DNA.200P2T6 Phenol inhibition 57 DNA.0N2T4 No inhibition 29 DNA.0N2T5 No inhibition 42 DNA.0N2T6 No inhibition 57 Study 1 DNA.5N2T4 No inhibition 29 DNA.5N2T5 No inhibition 42 DNA.5N2T6 No inhibition 57 DNA.10N2T4 No inhibition 29 DNA.10N2T5 No inhibition 42 DNA.10N2T6 No inhibition 57 DNA.15N2T4 No inhibition 29 DNA.15N2T5 No inhibition 42 DNA.15N2T6 No inhibition 57 DNA.25N2T4 No inhibition 29 DNA.25N2T5 No inhibition 42 DNA.25N2T6 No inhibition 57 DNA.75N2T4 Ammonia inhibition 29 DNA.75N2T5 Ammonia inhibition 42 DNA.75N2T6 Ammonia inhibition 57 DNA.100N2T4 Ammonia inhibition 29 DNA.100N2T5 Ammonia inhibition 42 DNA.100N2T6 Ammonia inhibition 57 DNA.250N2T4 Ammonia inhibition 29 DNA.250N2T5 Ammonia inhibition 42 DNA.250N2T6 Ammonia inhibition 57 nono2T3 No inhibition 16 noN2T4 Ammonia inhibition 23 noN2T8 Ammonia inhibition 60 noN2T9 Ammonia inhibition 85 noPhi2T4 Phenol inhibition 23 noPhi2T5 -

Tree Scale: 1 D Bacteria P Desulfobacterota C Jdfr-97 O Jdfr-97 F Jdfr-97 G Jdfr-97 S Jdfr-97 Sp002010915 WGS ID MTPG01

d Bacteria p Desulfobacterota c Thermodesulfobacteria o Thermodesulfobacteriales f Thermodesulfobacteriaceae g Thermodesulfobacterium s Thermodesulfobacterium commune WGS ID JQLF01 d Bacteria p Desulfobacterota c Thermodesulfobacteria o Thermodesulfobacteriales f Thermodesulfobacteriaceae g Thermosulfurimonas s Thermosulfurimonas dismutans WGS ID LWLG01 d Bacteria p Desulfobacterota c Desulfofervidia o Desulfofervidales f DG-60 g DG-60 s DG-60 sp001304365 WGS ID LJNA01 ID WGS sp001304365 DG-60 s DG-60 g DG-60 f Desulfofervidales o Desulfofervidia c Desulfobacterota p Bacteria d d Bacteria p Desulfobacterota c Desulfofervidia o Desulfofervidales f Desulfofervidaceae g Desulfofervidus s Desulfofervidus auxilii RS GCF 001577525 1 001577525 GCF RS auxilii Desulfofervidus s Desulfofervidus g Desulfofervidaceae f Desulfofervidales o Desulfofervidia c Desulfobacterota p Bacteria d d Bacteria p Desulfobacterota c Thermodesulfobacteria o Thermodesulfobacteriales f Thermodesulfatatoraceae g Thermodesulfatator s Thermodesulfatator atlanticus WGS ID ATXH01 d Bacteria p Desulfobacterota c Desulfobacteria o Desulfatiglandales f NaphS2 g 4484-190-2 s 4484-190-2 sp002050025 WGS ID MVDB01 ID WGS sp002050025 4484-190-2 s 4484-190-2 g NaphS2 f Desulfatiglandales o Desulfobacteria c Desulfobacterota p Bacteria d d Bacteria p Desulfobacterota c Thermodesulfobacteria o Thermodesulfobacteriales f Thermodesulfobacteriaceae g QOAM01 s QOAM01 sp003978075 WGS ID QOAM01 d Bacteria p Desulfobacterota c BSN033 o UBA8473 f UBA8473 g UBA8473 s UBA8473 sp002782605 WGS -

WO 2U11/154U12 a L

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date Χ 15 December 2011 (15.12.2011) WO 2U11/154U12 A l (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/415 (2006.01) A61K 9/20 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, (21) International Application Number: CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, PCT/DK201 1/050207 DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, 10 June 201 1 (10.06.201 1) KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, (25) Filing Language: English NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, (26) Publication Language: English SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: PA 2010 00506 10 June 2010 (10.06.2010) DK Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): LIFE- GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, CYCLE PHARMA A S [DK/DK]; Kogle Alle 4, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, DK-2970 H0rsholm (DK). -

Principios Activos Fotosensibles

PRINCIPIOS ACTIVOS FOTOSENSIBLES PROTEGE A TUS PRODUCTOS DE LA FOTODEGRADACIÓN PRINCIPIOS ACTIVOS FOTOSENSIBLES Adenosine Carbamazepine Digitoxin Heptacaine Methaqualone-1-oxide Phenothiazines Sulfisomidine Tinidazole Vitamin D Adrenaline Carbisocaine Digoxin Hexachlorophane Methotrexate Phenylbutazone Sulpyrine Tolmetin Vitamin E Adriamycin Carboplatin Dihydroergotamin Hydralazine Metronidazole Phenylephrine Suprofen Tretinoin Vitamin K1 Amidopyrin Carmustine Dihydropyridines Mifepristone Phenytoin Triamcinolone Vitamin K2 Hydrochlorothiazide Suramin Amidinohydrazones Cefotaxime Diltiazem Hydrocortisone Minoxidil Physostigmine Triamterene Warfarin Amiloride Cefuroxime axetil Diosgenin Mitomycin C Piroxicam Tauromustine (TCNU) Trifluoperazine Hydroxychloroquine Terbutaline 4-Aminobenzoic acid Cephaeline Diphenhydramine Hypochloride Mitonafide Pralidoxime Trimethoprim Aminophenazone Cephalexine Dipyridamole Ibuprofen Mitoxantrone Prednisolone Tetracyclines Ubidecarenone Thiazide Aminophylline Cephradine Dithranol Imipramin Molsidomine Primaquine Vancomycin Thiocolchicoside Aminosalicylic acid Chalcone Dobutamin Indapamide Morphine Proguanil Vinblastine Thioridazine Amiodarone Chloramphenicol Dopamine Indomethacin Nalidixic acid Promazine Vitamin A Thiorphan Amodiaquine Chlordiazepoxide Dothiepin Indoprofen Naproxen Promethazine Vitamin B (see also Thiothixene Amonafide Chloroquine Doxorubicin Isoprenaline Neocarzinostatin Proxibarbital riboflavine) Tiaprofenic acid Amphotericin B Chlorpromazine DTIC Isopropylamino- Nimodipine Psoralen -

Research Article Review Jmb

J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. (2017), 27(0), 1–7 https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1707.07027 Research Article Review jmb Methods 20,546 sequences and all the archaeal datasets were normalized to 21,154 sequences by the “sub.sample” Bioinformatics Analysis command. The filtered sequences were classified against The raw read1 and read2 datasets was demultiplexed by the SILVA 16S reference database (Release 119) using a trimming the barcode sequences with no more than 1 naïve Bayesian classifier built in Mothur with an 80% mismatch. Then the sequences with the same ID were confidence score [5]. Sequences passing through all the picked from the remaining read1 and read2 datasets by a filtration were also clustered into OTUs at 6% dissimilarity self-written python script. Bases with average quality score level. Then a “classify.otu” function was utilized to assign lower than 25 over a 25 bases sliding window were the phylogenetic information to each OTU. excluded and sequences which contained any ambiguous base or had a final length shorter than 200 bases were Reference abandoned using Sickle [1]. The paired reads were assembled into contigs and any contigs with an ambiguous 1. Joshi NA, FJ. 2011. Sickle: A sliding-window, adaptive, base, more than 8 homopolymeric bases and fewer than 10 quality-based trimming tool for FastQ files (Version 1.33) bp overlaps were culled. After that, the contigs were [Software]. further trimmed to get rid of the contigs that have more 2. Schloss PD. 2010. The Effects of Alignment Quality, than 1 forward primer mismatch and 2 reverse primer Distance Calculation Method, Sequence Filtering, and Region on the Analysis of 16S rRNA Gene-Based Studies. -

Syntrophic Butyrate and Propionate Oxidation Processes 491

Environmental Microbiology Reports (2010) 2(4), 489–499 doi:10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00147.x Minireview Syntrophic butyrate and propionate oxidation processes: from genomes to reaction mechanismsemi4_147 489..499 Nicolai Müller,1† Petra Worm,2† Bernhard Schink,1* a cytoplasmic fumarate reductase to drive energy- Alfons J. M. Stams2 and Caroline M. Plugge2 dependent succinate oxidation. Furthermore, we 1Faculty for Biology, University of Konstanz, D-78457 propose that homologues of the Thermotoga mar- Konstanz, Germany. itima bifurcating [FeFe]-hydrogenase are involved 2Laboratory of Microbiology, Wageningen University, in NADH oxidation by S. wolfei and S. fumaroxidans Dreijenplein 10, 6703 HB Wageningen, the Netherlands. to form hydrogen. Summary Introduction In anoxic environments such as swamps, rice fields In anoxic environments such as swamps, rice paddy fields and sludge digestors, syntrophic microbial communi- and intestines of higher animals, methanogenic commu- ties are important for decomposition of organic nities are important for decomposition of organic matter to matter to CO2 and CH4. The most difficult step is the CO2 and CH4 (Schink and Stams, 2006; Mcinerney et al., fermentative degradation of short-chain fatty acids 2008; Stams and Plugge, 2009). Moreover, they are the such as propionate and butyrate. Conversion of these key biocatalysts in anaerobic bioreactors that are used metabolites to acetate, CO2, formate and hydrogen is worldwide to treat industrial wastewaters and solid endergonic under standard conditions and occurs wastes. Different types of anaerobes have specified only if methanogens keep the concentrations of these metabolic functions in the degradation pathway and intermediate products low. Butyrate and propionate depend on metabolite transfer which is called syntrophy degradation pathways include oxidation steps of (Schink and Stams, 2006). -

Microbial Processes in Oil Fields: Culprits, Problems, and Opportunities

Provided for non-commercial research and educational use only. Not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use. This chapter was originally published in the book Advances in Applied Microbiology, Vol 66, published by Elsevier, and the attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author's benefit and for the benefit of the author's institution, for non-commercial research and educational use including without limitation use in instruction at your institution, sending it to specific colleagues who know you, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. All other uses, reproduction and distribution, including without limitation commercial reprints, selling or licensing copies or access, or posting on open internet sites, your personal or institution’s website or repository, are prohibited. For exceptions, permission may be sought for such use through Elsevier's permissions site at: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial From: Noha Youssef, Mostafa S. Elshahed, and Michael J. McInerney, Microbial Processes in Oil Fields: Culprits, Problems, and Opportunities. In Allen I. Laskin, Sima Sariaslani, and Geoffrey M. Gadd, editors: Advances in Applied Microbiology, Vol 66, Burlington: Academic Press, 2009, pp. 141-251. ISBN: 978-0-12-374788-4 © Copyright 2009 Elsevier Inc. Academic Press. Author's personal copy CHAPTER 6 Microbial Processes in Oil Fields: Culprits, Problems, and Opportunities Noha Youssef, Mostafa S. Elshahed, and Michael J. McInerney1 Contents I. Introduction 142 II. Factors Governing Oil Recovery 144 III. Microbial Ecology of Oil Reservoirs 147 A. Origins of microorganisms recovered from oil reservoirs 147 B. Microorganisms isolated from oil reservoirs 148 C. Culture-independent analysis of microbial communities in oil reservoirs 155 IV. -

Propionic Acid Degradation by Syntrophic Bacteria During Anaerobic Biowaste Digestion Propionic Acid Degradation Propionic WIREŁŁO

KARLSRUHERBERICHTE ZUR INGENIEURBIOLOGIE . MONIKA FELCHNER-Z WIREŁŁO Propionic Acid Degradation by Syntrophic Bacteria During Anaerobic Biowaste Digestion Propionic Acid Degradation Propionic WIREŁŁO . MONIKA FELCHNER-Z 49 . Monika Felchner-Z wirełło Propionic Acid Degradation by Syntrophic Bacteria During Anaerobic Biowaste Digestion Karlsruher Berichte zur Ingenieurbiologie Band 49 Institut für Ingenieurbiologie und Biotechnologie des Abwassers Karlsruher Institut für Technologie Herausgeber: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. J. Winter Propionic Acid Degradation by Syntrophic Bacteria During Anaerobic Biowaste Digestion by . Monika Felchner-Z wirełło Dissertation, Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT) Fakultät für Fakultät für Bauingenieur-, Geo- und Umweltwissenschaften Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 08. Februar 2013 Referenten: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. habil. Josef Winter Korreferenten: Prof. Dr.-Ing. E.h. Hermann H. Hahn, Ph.D. Prof. Dr hab. in˙z . Jacek Namie´snik Impressum Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT) KIT Scientific Publishing Straße am Forum 2 D-76131 Karlsruhe KIT Scientific Publishing is a registered trademark of Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. Reprint using the book cover is not allowed. www.ksp.kit.edu This document – excluding the cover – is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 DE License (CC BY-SA 3.0 DE): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/ The cover page is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivatives 3.0 DE License (CC BY-ND 3.0 DE): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0/de/ Print on Demand 2014 ISSN 1614-5267 ISBN 978-3-7315-0159-6 DOI: 10.5445/KSP/1000037825 Propionic Acid Degradation by Syntrophic Bacteria During Anaerobic Biowaste Digestion Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTOR-INGENIEURS von der Fakult¨at f¨ur Bauingenieur-, Geo- und Umweltwissenschaften des Karlsruher Instituts f¨ur Technologie (KIT) genehmigte DISSERTATION von Dipl.-Ing.