PUBLIC INQUIRY REPORT Review of Access List and Mandatory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telekom Malaysia

TELECOMMUNICATION TELEKOM MALAYSIA (T MK EQUITY, TLMM.KL) 28 July 2020 unifi Mobile joins prepaid bandwagon Company report HOLD Alex Goh (Maintained) [email protected] 03-2036 2280 Rationale for report: Company update Investment Highlights Price RM3.98 Fair Value RM4.15 52-week High/Low RM4.58/RM3.09 We maintain our HOLD call on Telekom Malaysia (TM) with unchanged forecasts and DCF-based fair value of RM4.15/share Key Changes based on a WACC of 7.4% and terminal growth rate of 2%. This Fair value implies an FY20F EV/EBITDA of 5x, at parity to its 2-year EPS average. YE to Dec FY19 FY20F FY21F FY22F TM’s unifi Mobile has cut its unlimited prepaid Internet data Revenue (RM mil) 11,434.2 11,345.2 11,419.1 11,547.2 under its #BEBAS plan to RM35/month from RM55/month, Core net profit (RM mil) 1,000.8 833.1 862.6 904.4 joining the same price points initiated by Maxis last month, and FD Core EPS (sen) 26.6 22.2 23.0 24.1 followed subsequently by Axiata Group’s Celcom. FD Core EPS growth (%) 58.3 (16.8) 3.5 4.8 Consensus Net Profit (RM mil) - 831.8 867.9 890.2 unifi Mobile is also offering weekly unlimited Internet pass for DPS (sen) 10.0 10.0 10.0 10.0 RM12, down from RM20. However, these unlimited passes PE (x) 14.9 18.0 17.3 16.5 appear to be only available for LTE data which means EV/EBITDA (x) 5.5 5.5 5.0 4.4 Div yield (%) 2.7 2.7 2.7 2.7 customers may need to purchase a separate data pass in areas ROE (%) 8.2 10.2 10.1 10.1 outside of unifi Mobile’s 4G coverage. -

Public Inquiry Report

Suruhanjaya Komunikasi dan Multimedia Malaysia Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission Public Inquiry Report Mandatory Standards for Quality of Service (Customer Service) 3 JULY 2021 This Public Inquiry Paper was prepared in fulfilment of subsections 55(1), (3) and (4), and sections 58 and 61 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 [Act 588]. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION ..................................................................... 4 SECTION 2: NEW MANDATORY STANDARDS ON CUSTOMER SERVICE ....... 6 SECTION 3: STANDARDS FOR QUALITY OF SERVICE (CUSTOMER SERVICE) ........................................................................... 11 SECTION 4: REPORTING TIMELINE AND INTERPRETATION OF THE STANDARDS ......................................................................... 53 SECTION 5: WAY FORWARD ................................................................... 58 2 ABBREVIATIONS AND GLOSSARY ASN GW Access Service Network Gateway BAS Broadband Access Service CMA Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 Commission Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission CPE Customer Premises Equipment IVRS Interactive Voice Response System MME Mobile Management Entity MS Mandatory Standards MSC Mobile Switching Centre MSQoS Mandatory Standards for Quality of Service Public Inquiry The Public Inquiry on the Proposal for New Mandatory Standards for Quality of Service (Customer Service) Public Inquiry The Public Inquiry Paper on the Proposal for New Paper Mandatory Standards for Quality of Service (Customer -

The Importance of Smartphone's Usage Among Malaysian

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 14, Issue 3 (Jul. - Aug. 2013), PP 112-118 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.Iosrjournals.Org The Importance of Smartphone’s Usage Among Malaysian Undergraduates Noor Mayudia Mohd Mothar, Prof. Dr. Musa B. Abu Hassan, Prof. Dr. Md Salleh B. Haji Hassan, Dr. Mohd Nizam Osman Faculty of Modern Language and Communication Universiti Putra Malaysia 43400 UPM Serdang Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia Fakulti Kepimpinan dan Pengurusan Universiti Islam Malaysia Bandar Baru Nilai 71800, Nilai, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia Faculty of Modern Language and Communication Universiti Putra Malaysia 43400 UPM Serdang Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia Faculty of Modern Language and Communication Universiti Putra Malaysia 43400 UPM Serdang Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia Abstract: Since its debut, smartphone had been steadily replacing the existence of the conventional mobile phone. The change was well accepted and proven by the smartphones’ surging sales throughout these years. Furthermore, smartphone become a necessity to universities students. Apart from allowing them to socially interact with others, it also can entertain as well as provide platform to search for information. Nowadays the smartphone could also be use to channel its owners’ personality. This research implies that pattern of smartphone’s usage was categories into four typologies that includes Information, Personal Identity, Integration and Social Interaction, and Entertainment. With data from 385 undergraduate students from public and private university in Malaysia, the researcher was able to conclude that the usage for personal identity was important to them. The results were able to clarify the students’ interest over their smartphone and confirm its popularity among youngsters. -

U Mobile and Celcom Extended Domestic Roaming Agreement for the Next Three Years

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE U MOBILE AND CELCOM EXTENDED DOMESTIC ROAMING AGREEMENT FOR THE NEXT THREE YEARS Kuala Lumpur, Thursday, 2 September 2010 - U Mobile Sdn Bhd and Celcom Axiata Berhad [formerly known as Celcom (Malaysia) Berhad] have extended their partnership on domestic roaming arrangement for another 3-year duration. This arrangement made effective 1 July 2010, and is an enhancement of the existing agreement. The Domestic Roaming agreement was signed by the Chief Executive Officer of U Mobile, Dr. Kaizad Heerjee, on behalf of U Mobile while the Chief Executive Officer of Celcom, Dato’ Sri Shazalli Ramly, signed on behalf of Celcom. The existing domestic roaming agreement between the two parties was first signed in year 2007 and was a landmark agreement, being the first such agreement of its kind in the country that allowed customers to enjoy complete nationwide mobile coverage at no additional cost to the users. Through this renewed domestic roaming arrangement with Celcom, U Mobile customers will continue to enjoy nationwide coverage and improved user experience, with seamless hand-over of voice calls from U Mobile’s 3G network to Celcom’s 2G network. Later in the year, U Mobile subscribers roaming on Celcom’s 2G network will also be able to access data services such as Mobile Internet, MMS and Content Downloads. 1 Dr. Kaizad Heerjee, the CEO of U Mobile said, “The seamless integration between U Mobile’s 3G network and Celcom’s 2G network will deliver an unparallel level of mobile communications to the end users who constantly need to stay connected.” “This move demonstrates the industry’s ability to arrive at a commercial agreement that helps meet the objective of the Ministry of Information Communication and Culture to benefit the consumers by providing nationwide coverage,” he added. -

Ipv6 Adoption, Current Scenario in Malaysia

APRICOT 2010, Feb 23 – Mar 5, 2010 IPv6 Adoption, the Current Scenario in Malaysia Raj Kumar M Senior Researcher, NAv6 [email protected] Outline • Government Initiatives on IPv6 • IPv6 Deployment in Malaysia • ISPs Current Status of IPv6 • IPv4 & IPv6 Address allocations • Awareness & Promotion • Training • IPv6 Forum & Working Group • General recommendations • Conclusion 2 Government Initiatives on IPv6 9 2004, National IPv6 Council, established by MEWC (MICC now) 9 To provide leadership, and strategic planning for IPv6 implementation 9 Members: MICC, MOF, EPU, MAMPU, MOSTI, MCMC, and ISPs 9 Mar 2005, National Advanced IPv6 Centre of Excellence (NAv6), established by MEWC 9 To spearhead IPv6 activities in Malaysia Awareness – Functions: Core Training Monitoring & R&D & HRD & Audit Promotion 3 National Agenda with respect to IPv6 MyICMS 886 Strategy RMK‐9 (2006‐2010) SERVICES INFRASTRUCTURE GROWTH Promoting Targeted Technologies for 1. High Speed Hard 1. Content Broadband Development New sources of growth 1. Multiservice (e.g. education, 2. 3G & Beyond Convergence entertainment, Networks games) 12.55 IPv6, Grid Computing and 3. Mobile TV 2. 3G Cellular 2. ICT Education Language engineering. The anticipated 4. Digital Networks Hub Multimedia Migration from IPv4 to IPv6 will spur R&D Broadcasting 3. Satellite 3. Digital Networks Multimedia activities in the areas of IPv6 compatible 5. Digital Home Receivers (set Soft top box) 6. Short Range applications, quality and security, which 4. Communicatio Communications 4. Next (e.g. RFID‐based) Generation n Devices (e.g. are new features available within the IPv6 VoIP phones) Internet 7. VoIP/Internet Protocol Protocol Telephony (IPv6) 5. Embedded Components, Source: http://www.epu.jpm.my/RM9/english/Chapter12.pdf 8. -

Digi.Com Fact Sheet

DiGi.Com Fact Sheet Corporate Info DiGi.Com Berhad is listed on Bursa Malaysia Securities Berhad and is part of the global telecommunications provider, Telenor Group. Its mobile service operations are undertaken by its wholly-owned subsidiary, DiGi Telecommunications Sdn Bhd. DiGi commenced operations in May 1995 when it launched its fully digital GSM1800 services, the first digital mobile communications service in Malaysia. In the last five years, DiGi’s revenue has grown to RM6.7 billion from RM4.9 billion with a subscriber base of 11.0 million. DiGi focuses on making it easy, keeping it relevant and providing the best deals to ensure excellent customer experience in mobile and internet services. DiGi has now expanded its HSPA+ enabled 3G network to 83% population coverage and increased its own and jointly built fibre network to more than 4,400 kilometres nationwide, building the vital backhaul connectivity needed to support always-on, high-speed data experience. With the completion of modernized network in 2013, DiGi will continue its focus on delivering higher quality network experience, stronger internet usage and positive overall customer satisfaction. DiGi’s presence as a leader in prepaid services has spearheaded in a number of industry benchmarks for simplicity and innovation. In addition, DiGi has also revitalised its postpaid services under DiGi Postpaid and DiGi Business to deliver quality voice and mobile internet services to individuals and corporate customers. Through its corporate initiative, Deep Green, DiGi is committed -

Telco, Service Providers Offer Free Data and Discounts During

Headline Telco, service providers offer free data and discounts during MCO MediaTitle The Malaysian Reserve Date 27 Mar 2020 Language English Circulation 12,000 Readership 36,000 Section News Page No 7 ArticleSize 604 cm² Journalist S BIRRUNTHA PR Value RM 19,026 Telco, service providers offer free data and discounts during MCO TM is providing its from time to time in the effort to customers with free LTE curb the spread of Covid-19. On another note, OCBC Bank hotspot pass and a 7-day (M) Bhd, together with its Islamic unlimited data pass banking subsidiary OCBC Al-Amin Bank Bhd, has announced by S BIRRUNTHA that it will absorb the RM1 auto- mated teller machine (ATM) cash MALAYSIAN telecommunica- withdrawal fee levied to its cus- tion companies (telcos) and tomers for using another bank's service providers have taken the ATM in the country. initiative to ensure that customers OCBC Bank head of consumer stay connected during the Move- financial services Lim Wyson said ment Control Order (MCO) by the initiative is part of the bank's offering free unlimited data concerted efforts to encourage access to telco users, as well as people to comply with the MCO. discounts on bill payments for "By absorbing the RM1 cash Malaysians. withdrawal fee, we are removing Telekom Malaysia Bhd (TM) yet another hurdle to getting said it will continually monitor people home more quickly," he the developments of the situa- said in a statement. tion and adapt its services Lim added that to minimise the to help customers, whenever use of ATMs beyond when abso- needed. -

Mobile Cellular 3+7.Xlsx

PUBLIC CELLULAR NUMBERS : MOBILE CELLULAR (3+7) PREFIX 01Y SUBSCRIBER NUMBER SERVICE PROVIDER 200 0000 - 299 9999 DiGi Telecommunications Sdn Bhd 300 0000 - 349 9999 XOX Com Sdn Bhd 350 0000 - 359 9999 Packet One Networks Sdn Bhd 360 0000 - 399 9999 DiGi Telecommunications Sdn Bhd 400 0000 - 419 9999 Celcom Axiata Berhad 420 0000 - 439 9999 Maxis Mobile Services Sdn Bhd 10 440 0000 - 459 9999 Packet One Networks Sdn Bhd 460 0000 - 469 9999 DiGi Telecommunications Sdn Bhd 500 0000 - 549 9999 Tune Talk Sdn Bhd 550 0000 - 559 9999 Packet One Networks Sdn Bhd 560 0000 - 569 9999 DiGi Telecommunications Sdn Bhd 570 0000 - 599 9999 Celcom Axiata Berhad Updated: August 2012 Mobile Cellular (3+7) . Page 1 of 5 PUBLIC CELLULAR NUMBERS : MOBILE CELLULAR (3+7) PREFIX 01Y SUBSCRIBER NUMBER SERVICE PROVIDER 600 0000 - 649 9999 Baraka Telecom Sdn Bhd 650 0000 - 659 9999 Packet One Networks Sdn Bhd 660 0000 - 669 9999 DiGi Telecommunications Sdn Bhd 700 0000 - 719 9999 Maxis Mobile Services Sdn Bhd 760 0000 - 769 9999 DiGi Telecommunications 10 770 0000 - 819 9999 Tune Talk Sdn Bhd 820 0000 - 829 9999 DiGi Telecommunications Sdn Bhd 830 0000 - 879 0000 XOX Com Sdn Bhd 880 0000 - 889 9999 DiGi Telecommunications Sdn Bhd 890 0000 - 899 9999 Maxis Mobile Services Sdn Bhd 900 0000 - 989 9999 DiGi Telecommunications Sdn Bhd Updated: August 2012 Mobile Cellular (3+7) . Page 2 of 5 PUBLIC CELLULAR NUMBERS : MOBILE CELLULAR (3+7) PREFIX 01Y SUBSCRIBER NUMBER SERVICE PROVIDER 12 200 0000 - 999 9999 Maxis Mobile Services Sdn Bhd 13 200 0000 - 999 9999 Celcom Axiata -

Symptoms Versus Problems (SVP) in Household High Speed Broadband (HSBB): Regaining Momentum for Unifi, Malaysia”

“Symptoms versus problems (SVP) in household high speed broadband (HSBB): regaining momentum for Unifi, Malaysia” Noor N. Kader Ali AUTHORS Bin Y. Soon Lee S. Goh Nur A. Ahmad Razi Noor N. Kader Ali, Bin Y. Soon, Lee S. Goh and Nur A. Ahmad Razi (2015). ARTICLE INFO Symptoms versus problems (SVP) in household high speed broadband (HSBB): regaining momentum for Unifi, Malaysia. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 13(2-si), 330-346 RELEASED ON Tuesday, 28 July 2015 JOURNAL "Problems and Perspectives in Management" FOUNDER LLC “Consulting Publishing Company “Business Perspectives” NUMBER OF REFERENCES NUMBER OF FIGURES NUMBER OF TABLES 0 0 0 © The author(s) 2021. This publication is an open access article. businessperspectives.org Problems and Perspectives in Management, Volume 13, Issue 2, 2015 Noor N. Kader Ali (Malaysia), Bin Y. Soon (Malaysia), Lee S. Goh (Malaysia), Nur A. Ahmad Razi (Malaysia) Symptoms versus problems (SVP) in household high speed broadband (HSBB): regaining momentum for Unifi, Malaysia Abstract Problem identification is a talent and skill set required in all leaders. The objective of this study is to reveal an improved research method by integrating mixed-method research combined with problem identification method (using symptoms versus problems (SVP) framework) for telco service providers. The SVP framework discovers the primary causes to the decrease in revenue growth rates. Malaysia’s household broadband penetration rate grew from 15.2% (2007) to 67.1% (2013). Meanwhile, the growth rate for Unifi, offered by Telekom Malaysia (TM), decreased from 104% (2012) to 30% (2013). Why? There are eight causes, specifically; not prioritizing 4G LTE license; obligating social services to rural areas; providing 20-30 Mbps wireless broadband packages by the competitors; offering less competitive price; not covering all zones; offering less favorable service contracts; offering limited packages; and receiving customer complaints. -

Network Performance Report 2016 Measuring Broadband and Voice Performance

Network Performance Report 2016 Measuring broadband and voice performance Published: 27 January 2017 Contents Section Page 1 Executive Summary 3 2 Wireless broadband performance 5 3 Wired broadband performance 25 4 Voice call performance 30 2 Executive Summary This report provides information on the results of network performance measurement conducted by MCMC across six regions within Malaysia. The respective regions are Central, Southern, Northern, Eastern, Sarawak and Sabah. The measurement involves measuring performance of mobile and fixed wireless broadband, wired broadband and voice on public cellular service. Service providers evaluated were Celcom, DiGi, Maxis and U Mobile for public cellular service and mobile broadband. As for fixed wireless broadband the service providers measured were Packet One (now known as Webe) and YES. Lastly, on the wired broadband network performance, service providers involved were Maxis, Time DotCom and Telekom Malaysia (TM). It is important to note that the results shown here does not reflect the Malaysian-wide performance and is limited to the areas being measured. However, the measurements were done in major cities for each regional areas to reflect on the performance in high demand areas. The results provide snapshots of performance from January to December 2016. During which all operators involved in the assessment may have carried out varying degree of network maintenance and modernization on their network which may have impacted their results. All results were gathered based on the offered service at the particular tested areas. For mobile broadband, the user equipment (UE) or mobile phones were not locked into any particular technology band but measurements were done in 3G and LTE coverage areas. -

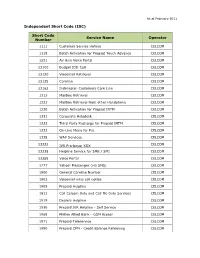

(ISC) Short Code Number Service Name Operator

As at February 2011 Independent Short Code (ISC) Short Code Service Name Operator Number 1111 Customer Service Hotline CELCOM 1118 Batch Activation for Prepaid Touch Advance CELCOM 1221 Air Asia Voice Portal CELCOM 13100 Budget IDD Call CELCOM 13120 Voicemail Retrieval CELCOM 13125 Careline CELCOM 13162 Indonesian Customers Care Line CELCOM 1313 Mailbox Retrieval CELCOM 1323 Mailbox Retrieval from other Handphone CELCOM 1330 Batch Activation for Prepaid INTM CELCOM 1331 Corporate Helpdesk CELCOM 1332 Third Party Recharge for Prepaid INTM CELCOM 1333 On-Line Menu for Pre CELCOM 1338 WAP Services CELCOM 13322 IVR Pra-bayar XOX CELCOM 13338 Helpline Service for SME / SMI CELCOM 13388 Voice Portal CELCOM 1777 Yahoo! Messenger (via SMS) CELCOM 1900 General Careline Number CELCOM 1903 Voicemail miss call notice CELCOM 1909 Prepaid Helpline CELCOM 1911 Call Celcom Only and Call Me Only Services CELCOM 1919 Dealers Helpline CELCOM 1930 Prepaid IVR Helpline - Self Service CELCOM 1968 Philleo Allied Bank - GSM Access CELCOM 1971 Prepaid Teleservice CELCOM 1990 Prepaid CPM - Credit Balance Retrieving CELCOM As at February 2011 Short Code Service Name Operator Number 1999 Voicemail Retrieve 3G Videomail CELCOM 13300 IVR (Interactive Voice Recorder) - Berita CELCOM 13301 IVR (Interactive Voice Recorder) - Muzik CELCOM 13302 IVR (Interactive Voice Recorder) - Karaoke CELCOM 13362 Careline - Bahasa Bengali CELCOM 13380 Careline - Bahasa Tamil CELCOM 13391 Careline - Bahasa Malaysia CELCOM 110 SMS Centre DiGi 121 Voice Mail DiGi 13122 IVR Broadcast DiGi -

A REPORT on a PUBLIC INQUIRY Access Pricing

A REPORT ON A PUBLIC INQUIRY Access Pricing 30 November 2005 This Public Inquiry Report was prepared in fulfilment of Section 65 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998. CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND GLOSSARY IV SUMMARY OF THE MCMC FINAL VIEWS ON ACCESS PRICING VIII 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. Public Inquiry Process 1 1.2. The MCMC’s legislative obligations 1 1.3. Consultation Process 1 1.4. Submissions Received 3 2. STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT 5 3. PRINCIPLES IN SETTING ACCESS PRICES 6 3.1. General Comments 6 3.2. Statement on Access Pricing Principles 9 3.3. Criteria for regulatory intervention 10 3.4. Use of LRIC methodology in the Malaysian context 13 3.5. Criteria for adopting LRIC costing methodology 16 3.6. Practical implementation of LRIC costing model 20 4. TSLRIC FOR FACILITIES/SERVICES OVER FIXED NETWORKS 32 4.1. Cost of capital 32 4.2. Model options 34 4.3. Fixed Network Origination/Termination Services 38 4.4. Equal Access (PSTN) Service 43 4.5. Interconnect Link Service 45 4.6. Private Circuit Completion Service 48 4.7. Domestic Network Transmission Service 52 4.8. Internet Access Call Origination Service 55 4.9. Domestic Connectivity to International Services 56 i 4.10. Network Co-Location Service 57 4.11. Full Access Service 59 4.12. Line Sharing Service 62 4.13. Bitstream Services 64 4.14. Sub-loop Service 67 4.15. Digital Subscriber Line Resale Service 69 5. TSLRIC FOR FACILITIES/SERVICES OVER IP NETWORKS 70 5.1. Model Description and Run Options 70 5.2.