SCSL Press Clippings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Taylor and the Sierra Leone Special Court Kathy Ward

Human Rights Brief Volume 11 | Issue 1 Article 3 2003 Might v. Right: Charles Taylor and the Sierra Leone Special Court Kathy Ward Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/hrbrief Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Ward, Kathy. "Might v. Right: Charles Taylor and the Sierra Leone Special Court." Human Rights Brief 11, no. 1 (2003): 8-11. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Human Rights Brief by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ward: Might v. Right: Charles Taylor and the Sierra Leone Special Court Might v. Right: Charles Taylor and the Sierra Leone Special Court by Kathy Wa rd N JUNE 2003, THE SPECIAL COURT FOR SIERRA LEONE series of economic measures imposed by the Security Council. T h e s e ( Special Court) announced it had indicted Liberian Pre s i d e n t m e a s u res included an arms embargo, diamond embargo, and a travel ban Charles Taylor on war crimes charges related to his role in the against Taylor and other members of his inner circle. The hope was that war in Sierra Leone. The announcement came just as Ta y l o r these measures would strangle the flow of arms that fueled Ta y l o r’s mili- a rI r i ved in Ghana for peace talks, which diplomats hoped would bring a t a ry activities in the region, and that the diamond and travel bans would quick end to the Liberian war and would provide Taylor with a graceful limit his funding and force him to stop fueling rebel wars in neighboring exit from powe r. -

SCSL Press Clippings

SPECIAL COURT FOR SIERRA LEONE PRESS AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICE PRESS CLIPPINGS Enclosed are clippings of local and international press on the Special Court and related issues obtained by the Outreach and Public Affairs Office as at: Thursday, 22 May 2008 Press clips are produced Monday through Friday. Any omission, comment or suggestion, please contact Martin Royston-Wright Ext 7217 2 Local News Moses Blah Ends Testimony at Taylor Trial / Awoko Page 3 Special Court Told of Johnny Paul’s Death / Independent Observer Page 4 Njala Bags National Mooting Competition / Awoko Page 5 75 Million British Pounds Spent On Taylor's Trial So Far / Concord Times Page 6-8 International News (Untitled) / BBC World Service Trust Pages 9-10 Blah Faces Cross Examination / The Inquirer Page 11 Blah Closes in on Taylor / Heritage Pages 12-14 Roland Duo’s Atrocities Revealed / National Chronicle Page 15 Ivory Coast’s Involvement: The Light in Moses Blah’s... / National Chronicle Page 16 Defense Lawyer X-Ray Blah Today / Liberian Express Pages 17-18 Experts Views on Taylor’s Fate / Liberian Express Pages 19-20 Blah Uncovers Hidden Things / The Analyst Pages 21-22 'I Had No Hands in the Assassination of Masquita': Moses Blah / Cocorioko Page 23 Moses Blah Ends Testimony at Taylor Trial / Patriotic Vanguard Page 24 UNMIL Public Information Office Complete Media Summaries / UNMIL Pages 25-26 Experts Warn of Violence After Guinea President Fires Prime Minister / VOA Pages 27-28 3 Awoko Thursday, 22 May 2008 4 Independent Observer Thursday, 22 May 2008 5 Awoko Thursday, 22 May 2008 6 Concord Times online Wednesday, 21 May 2008 Opinion 75 Million British Pounds Spent On Taylor's Trial So Far By Pel Koroma A recent report published in the Daily Mail newspaper (UK) made the revelation that such a huge amount of money has been spent so far on the ongoing trial of Charles Taylor at Special Court for Sierra Leone sitting in The Hague. -

Not Self-Evident That Taylor Should Have Known That Some of It Was Given Instead to the RUF by Yeaten"

possible way to supplement their meagre income". The Defence argues that nonetheless it is "not self-evident that Taylor should have known that some of it was given instead to the RUF by Yeaten". 5567 Further, the Accused denies that he supplied arms or ammunition to the RUF during the Indictment period .5568 2576. Concerning Yeaten's alleged role in this "private enterprise", the Defence relies on evidence from the Accused, TFI-371, DCT-008, Moses Blah, TFI-567, Sam Kolleh, Varmuyan Sherif, Abu Keita, Dauda Arona Fornie, and Issa Sesay, as well as Exhibit P-O18. Evidence Prosecution Witness Moses Blah 2577. Witness Moses Blah, Inspector General of the NPFL from 1990 to 1997,5569 Liberian Ambassador of Libya and Tunisia following Taylor's election to 2000,5570 and Vice President of Liberia from 2000 to 2003,5571 testified that he first met Benjamin Yeaten in Tajura Camp in Libya when Yeaten was about 14 to 15 years old. Because Yeaten was very effective in training, Charles Taylor recognised him and drew him nearer to him by appointing him to be his bodyguard and to be director of certain units that would be close to the President at the time. Eventually Yeaten became the Director of the SSS.Yeaten maintained his relationship with Taylor until Taylor left Liberia.5572 Only Taylor could give Yeaten orders. Blah stated that "[n]obody could disobey an order from Taylor. You would be punished severely, including myself We could not disobey his orders".5573 2578. Blah testified that in 2003 Yeaten took a group of Liberian men who had been wounded in battle to the Mahare River and executed them. -

Media Reporting of War Crimes Trials and Civil Society Responses in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone

Media Reporting of War Crimes Trials and Civil Society Responses in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone Abou Binneh-Kamara This is a digitised version of a dissertation submitted to the University of Bedfordshire. It is available to view only. This item is subject to copyright. Media Reporting of War Crimes Trials and Civil Society Responses in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone By Abou Bhakarr M. Binneh-Kamara A thesis submitted to the University of Bedfordshire in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. January, 2015 ABSTRACT This study, which seeks to contribute to the shared-body of knowledge on media and war crimes jurisprudence, gauges the impact of the media’s coverage of the Civil Defence Forces (CDF) and Charles Taylor trials conducted by the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) on the functionality of civil society organizations (CSOs) in promoting transitional (post-conflict) justice and democratic legitimacy in Sierra Leone. The media’s impact is gauged by contextualizing the stimulus-response paradigm in the behavioral sciences. Thus, media contents are rationalized as stimuli and the perceptions of CSOs’ representatives on the media’s coverage of the trials are deemed to be their responses. The study adopts contents (framing) and discourse analyses and semi-structured interviews to analyse the publications of the selected media (For Di People, Standard Times and Awoko) in Sierra Leone. The responses to such contents are theoretically explained with the aid of the structured interpretative and post-modernistic response approaches to media contents. And, methodologically, CSOs’ representatives’ responses to the media’s contents are elicited by ethnographic surveys (group discussions) conducted across the country. -

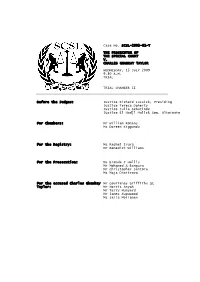

Case No. SCSL-2003-01-T the PROSECUTOR of the SPECIAL

Case No. SCSL-2003-01-T THE PROSECUTOR OF THE SPECIAL COURT V. CHARLES GHANKAY TAYLOR WEDNESDAY, 15 JULY 2009 9.30 A.M. TRIAL TRIAL CHAMBER II Before the Judges: Justice Richard Lussick, Presiding Justice Teresa Doherty Justice Julia Sebutinde Justice El Hadji Malick Sow, Alternate For Chambers: Mr William Romans Ms Doreen Kiggundu For the Registry: Ms Rachel Irura Mr Benedict Williams For the Prosecution: Ms Brenda J Hollis Mr Mohamed A Bangura Mr Christopher Santora Ms Maja Dimitrova For the accused Charles Ghankay Mr Courtenay Griffiths QC Taylor: Mr Morris Anyah Mr Terry Munyard Mr James Supuwood Ms Salla Moilanen CHARLES TAYLOR Page 24457 15 JULY 2009 OPEN SESSION 1 Wednesday, 15 July 2009 2 [Open session] 3 [The accused present] 4 [Upon commencing at 9.30 a.m.] 09:31:08 5 PRESIDING JUDGE: Good morning. We will take appearances 6 first, please. 7 MS HOLLIS: Good morning Mr President, your Honours, 8 opposing counsel. This morning for the Prosecution, Mohamed A 9 Bangura, Christopher Santora, Maja Dimitrova and myself Brenda J 09:31:38 10 Hollis. And, Mr President, just to bring to your attention, 11 there are two quick matters the Prosecution would ask to address 12 before the accused recommences his testimony. 13 PRESIDING JUDGE: Yes, thank you, Ms Hollis. For the 14 Defence, Mr Griffiths? 09:32:00 15 MR GRIFFITHS: Good morning. For the Defence today, myself 16 Courtenay Griffiths, assisted by my learned friends Mr Morris 17 Anyah, Mr Terry Munyard and Cllr Supuwood. Also with us is Salla 18 Moilanen, our case manager. -

Republic of Liberia Appendices

TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION The Palava Hut or Peace Forums REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION Volume Three: APPENDICES Title XII: Towards National Reconciliation and Dialogues: The Palava Hut or Peace Forums Volume THREE, Title XII i PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/0cd0ff/ TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION The Palava Hut or Peace Forums ii Volume THREE, Title XII PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/0cd0ff/ TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION The Palava Hut or Peace Forums Final Statement from the Commission Nearly three and half years ago, we embarked upon a journey on behalf of the people of Liberia with a simple mission to explain how Liberia became what it is today and to advance recommendations to avert a repetition of the past and lay the foundation for sustainable national peace, unity, security and reconciliation. Considering the complexity of the Liberian conflict, the intractable nature of our socio-cultural interactions, the fluid political and fragile security environment, we had no illusion of the task at hand and, embraced the challenge as a national call to duty; a duty we commi6ed ourselves to accomplishing without fear or favor. Today, we have done just that! With gratitude to the Almighty God, the Merciful Allah and our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, we are both proud and honored to present our report to the people of Liberia, the Government of Liberia, the President of Liberia and the International Community who are “moral guarantors” of the Liberian peace process. This report is made against the background of rising expectations, fears and anxiety. -

Liberian Studies Journal

2J VOLUME XXVI, 2001 Number 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL LIBERIA 8°N B°N MONSERRADO MARSI B 66N 66N MILES 0 50 MARYLAN GuocrOphr Otporlinen1 10°W VW Urifirsity el Pillsque ilk al Jolmitava Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editorial Policy The Liberian Studies Journal is dedicated to the publication of original research on social, political, economic, scientific, and other issues about Liberia or with implications for Liberia. Opinions of contributors to the Journal do not necessarily reflect the policy of the organizations they represent or the Liberian Studies Association, publishers of the Journal. Manuscript Requirements Manuscripts intended for consideration should not exceed 25 typewritten, double-spaced pages, with margins of one-and-a-half inches. The page limit includes graphs, references, tables and appendices. Authors must, in addition to their manuscripts, submit a computer disk of their work, preferably in WordPerfect 6.1 for Windows. Notes and references should be placed at the end of the text with headings, e.g., Notes; References. Notes, if any, should precede the references. The Journal is published in June and December. Deadline for the first issue is February, and for the second, August. Manuscripts should include a title page that provides the title of the text, author's name, address, phone number, and affiliation. All works will be reviewed by anonymous referees. Manuscripts are accepted in English and French. Manuscripts must conform to the editorial style of either the Chicago Manual of Style (the preferred style), or the American Psychological Association (APA) or Modern Language Association (MLA). -

1 Arms Flows Liberia Bp 11.03

November 3, 2003 Weapons Sanctions, Military Supplies, and Human Suffering: Illegal Arms Flows to Liberia and the June-July 2003 Shelling of Monrovia A Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper Introduction...................................................................................................................................................2 Arms, Abuses, and Liberia’s Warring Factions.............................................................................4 The Rebel Push on Monrovia ..................................................................................................................5 “World War III”: The Human Toll of Indiscriminate Shelling in Monrovia.....................7 Tracing the Mortar Rounds Used by the LURD Rebels ..............................................................14 Guinea’s history of support for LURD .........................................................................................15 The Caliber and Origin of Mortars, Munitions Used by LURD ..........................................17 Arms Procurement by Guinea ..........................................................................................................18 Flight of June 30, 2003....................................................................................................................22 Flight of August 5, 2003.................................................................................................................22 Transfer from Guinea and Use in Liberia.....................................................................................23 -

Liberia’S Shipping Register

Recommendations contained on page 1 2nd edition:This report now incorporates a study by the International Transport Workers Federation (ITF) of the part played by revenues generated from Liberia’s shipping register. Taylor-made The Pivotal Role of Liberia’s Forests and Flag of Convenience in Regional Conflict A Report by Global Witness in conjunction with the International Transport Workers Federation (ITF). September 2001 Taylor-made— The Pivotal Role of Liberia’s Forests and Flag of Convenience in Regional Conflict Recommendations Preface The UN Security Council should: Through the imposition of targeted sanctions, G Immediately impose a total embargo on the exportation and the international community has transportation of Liberian timber, and its importation into other demonstrated its concern over the threat countries. Such an embargo should remain in place until it can be Liberia poses to regional security. Despite demonstrated that the trade does not contribute to the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) in Sierra Leone and armed militias in Liberia, and recent overtures, this threat is still real: that it is carried out in a transparent manner (as referred to in para of Liberia continues to support the rebels of the the Report of the Panel of Experts appointed pursuant to UN Security Council Revolutionary United Front, and continues to Resolution () paragraph in relation to Sierra Leone). import armaments in contravention of the G Conduct further investigations into the Liberian timber industry, particularly the Oriental Timber Company (OTC), to enable the United sanctions. Nations Security Council (UNSC) and other members of the Liberia’s timber and shipping register are international community to gain a comprehensive understanding of the two key sources of revenue for the Taylor role of this industry in Charles Taylor’s presidency and the conflict in Sierra Leone and, increasingly, Lofa County in Northern Liberia. -

Taylor Trial Transcript

Case No. SCSL-2003-01-T THE PROSECUTOR OF THE SPECIAL COURT V. CHARLES GHANKAY TAYLOR TUESDAY, 20 MAY 2008 9.30 A.M. TRIAL TRIAL CHAMBER II Before the Judges: Justice Teresa Doherty, Presiding Justice Richard Lussick Justice Julia Sebutinde Justice Al Hadji Malick Sow, Alternate For Chambers: Mr William Romans Ms Carolyn Buff For the Registry: Ms Rachel Irura For the Prosecution: Mr Stephen Rapp Ms Brenda J Hollis Ms Maja Dimitrova For the accused Charles Ghankay Mr Courtenay Griffiths QC Taylor: Mr Terry Munyard Mr Morris Anyah Ms Logan Hambrick CHARLES TAYLOR Page 10236 20 MAY 2008 OPEN SESSION 1 Tuesday, 20 May 2008 2 [Open session] 3 [The accused present] 4 [Upon commencing at 9.30 a.m.] 09:31:54 5 PRESIDING JUDGE: Good morning. I note appearances are as 6 before. 7 MR GRIFFITHS: Good morning, your Honour, counsel opposite. 8 Appearances are as yesterday. 9 PRESIDING JUDGE: Mr Rapp? 09:32:10 10 MR RAPP: That is correct, your Honour. 11 PRESIDING JUDGE: If there are no other matters I will 12 remind the witness of his oath. 13 Mr Witness, I again remind you this morning, as I've done 14 on other mornings, that you have taken the oath to tell the 09:32:21 15 truth, the oath continues to be binding on you and you must 16 answer questions truthfully. 17 THE WITNESS: Your Honour. 18 PRESIDING JUDGE: Very well. Please proceed, Mr Griffiths. 19 WITNESS: MOSES ZEH BLAH [On former oath] 09:32:36 20 CROSS-EXAMINATION BY MR GRIFFITHS: [Continued] 21 Q. -

SCSL Press Clippings

SPECIAL COURT FOR SIERRA LEONE PRESS AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICE Thousands attended yesterday’s Episcopal Ordination of Fr. Edward Tamba Charles as Catholic Archbishop of Freetown and Bo. The ceremony took place at the National Stadium. PRESS CLIPPINGS Enclosed are clippings of local and international press on the Special Court and related issues obtained by the Outreach and Public Affairs Office as at: Thursday, 15 May 2008 Press clips are produced Monday through Friday. Any omission, comment or suggestion, please contact Martin Royston-Wright Ext 7217 2 Local News Crunch Time at Taylor Trial, But His Lawyer... / New Citizen Page 3 Ex-President Testifies in Taylor’s Trial Today / The News Pages 4-5 Special Court Chief Prosecutor on Taylor’s ‘Stolen’ Assets / The News Page 6 Special Court Delivers Another Judgement at 10am Today / Independent Observer Page 7 International News Liberian Commanders 'Ate Human Innards' / AFP Page 8 Gadhafi helped Taylor take over Liberia / AP Pages 9-10 Charles Taylor's Former Deputy Testifies in Trial / Reuters Page 11 Taylor’s Vice-President Testifies / BBC Pages 12-13 Charles Taylor's Former Deputy Testifies at...Trial / VOA Page 14 Blah Testifies Against Former Comrade Taylor / SABC Page 15 (Untitled) / BBC World Service Trust Pages 16-17 Blah’s “419s” Exposed / Plain Truth Pages 18-19 Sirleaf, Blah Give Legitimacy to Special Court’s Case... / National Chronicle Page 20 Defiant Blah Faces Taylor Today / New Democrat Page 21 Ex-RUF Commander Links Taylor to Bockarie’s, Ivorian... / New Democrat Pages 22-25 -

POL100042004ENGLISH.Pdf

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL This report covers the period January to December 2003 CHI"'''' PACIFIC OCEAN >If.."" ( ,-� \ ) 1,",01'" ... , / �" I PACIFIC OCEAN """"'" , " INDIAN OCEAN \, r ,0 ,> I 1.\� .,- First published in 2004 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WCl X ODW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org e Copyright Amnesty International Publlcalions 2004 ISBN: 0·86210·354·1 AI Index: POl 101004/2004 Original language: English Printed by: The Alden Press Osney Mead, Oxford United Ki ngdom Cover design by Synergy Maps by Andr�s Bereznay, wwwhistoryonmaps.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording and/or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL REPORT 2004 ERRATA Rwanda Page 71, column 2, paragraph S. hne7 should read: end of the year, the ICTRhad delivered 17judgments Brazil Page 103. column 2, paragraph 4, line S should read· ... Adenllson 8arbosa da Silva and Joseilton Jose dos Santos •.. Thailand Page 192. column 2, paragraph 2, line 3 should read bodies were found in a fiver on the Thai-Myanmar border Jordan Page 288. column 2, paragraph 2, line I should read e Journalist Muhannad Mubaidin served a six... CONTENTS CONTENTS Preface/ l A message from the Secretary Generall3 Building an international human rights agenda/5 PART 1 Africa regional overview/28·30 A-Z country entries/31