Struggles After the Whistle Upon Meeting Leon Mckenzie for the First

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 8 | the Millers Vs Waltham Abbey

THE OFFICIAL MATCHDAY PROGRAMME OF AVELEY FOOTBALL CLUB PARKLIFE MONDAY 28TH OCTOBER 2019 | 7.45PM KICK OFF ISSUE 8 | THE MILLERS VS WALTHAM ABBEY FREE AVELEY FOOTBALL CLUB PARKSIDE, PARK LANE, AVELEY, ESSEX, RM15 4PX TELEPHONE: 07516 934890 VISIT US AT: https://www.pitchero.com/clubs/aveley FULL MEMBERS OF THE FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION AFFILIATED TO ESSEX COUNTY FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION MEMBERS OF THE ISTHMIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE AVELEY FOOTBALL(INCORPORATED MA CLUBRCH 2014) LIMITED COMPANY NUMBER 08943550 VAT REGISTERED DIRECTORS: GRAHAM GENNINGS, CRAIG JOHNSON, ALAN SUTTLING, LYNN JOHNSON, GERRY DALY PATRONS: PHIL HUNTER, KEN SUTLIFF, ALAN SUTTLING PRESIDENT: KEN CLAY CHAIRMAN: GRAHAM GENNINGS | 07801 356451 [email protected] VICE CHAIRMAN: ALAN SUTTLING | 01375 400741 CHIEF EXECUTIVE: CRAIG JOHNSON | 07946 438540 [email protected] FINANCIAL CONTROLLER: LYNN JOHNSON [email protected] MATCH SECRETARY: TERRY KING | 01708 557596 MARKETING MANAGER: JAMIE MANKTELOW [email protected] COMMERCIAL MANAGER: RICHARD CHAMBERS [email protected] Important Club Notes: The Isthmian Football League strongly supports the FA Statement that there should be a zero-tolerance approach against racism and all forms of discrimination. Accordingly, any form of discrimination abuse whether it's based on race or ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender, faith, age, ability, or any other will be reported to the Football Association for action by that Administration. Aveley Football Club accets no liability for acidents to visitors, damage to vehicles or loss of contents whilst in the grounds or its precincts. The floodlighting towers carry a high voltage and therefore can be dangerous to anyone attempting to climb them. WELCOME TO PARKSIDE CRAIG JOHNSON Good evening, and a warm welcome to Parkside for News from the hospital on Saturday evening, was tonight’s , Velocity Cup Group 2 match. -

Lane, Posh V Arsenal !

Please Take Care of our Environment Recycle this Newsletter if no longer required IN POSH WE TRUST Patron :- Tommy Robson Members of Supporters Direct, The Football Supporters’ Federation and the Peterborough Council for Voluntary Service. Sponsored by ‘CHARTERS’ and ‘OAKHAM ALES’ NEWSLETTER No 42 March 2015 Minutes of Annual General Meeting Pete’s ‘Memory’ Lane, Posh v Arsenal ! Vote for your LEGENDS TEAM of the Decade Posh Trust MUSEUM Update Visit our website: www.theposhtrust.co.uk E-Mail: [email protected] Registered as a Society under the Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014. Registration No. 29533R with the Financial Conduct Authority. THE POSH SUPPORTERS’ TRUST Chairman John Henson, Secretary, Ray Cole Treasurer Geoff Callen Directors Barry Bennett, Keith Jennings, Walter Moore. John Lawrence. Ken Storey. Co-opted David Martin Patron Tommy Robson. Consultant Peter Lloyd. The Posh Supporters’ Trust, is a democratic not-for-profit organisation of supporters, committed to strengthening the voice of supporters in the decision-making process at Peterborough United Football Club. We seek to improve the links between the club and the community it serves, and help the club to grow to the highest level. Our Mission : To bring Peterborough United Football Club, Posh fans and the local community closer together. To help disadvantaged and deserving fans to go to a match for free under the "Smile Ticket" scheme. To help the football club by increasing the Posh fan base through our "New Posh Fans Initiative." To support football related activities locally through sponsorship and donations whenever possible. To have a substantial membership in order to represent the views of fans at meetings with the football club and to promote their interests. -

Hertford Town Fc 2019/20 Official Matchday Programme

HERTFORD TOWN FC 2019/20 OFFICIAL MATCHDAY PROGRAMME BETVICTOR LEAGUE SOUTH CENTRAL VS CHIPSTEAD THE ACRE CARS STADIUM SATURDAY FEBRUARY 22ND 3.00PM TEMPORA MUTANUR NOS ET MUTAMUR ILLIS VS CHIPSTEAD THE ACRE CARS STADIUM Saturday February 22nd (3pm) The Isthmian Football League strongly supports the FA statement that there should be a zero tolerance approach against racism and all forms of discrimination. Accordingly any form of discriminatory abuse whether it be based on race or ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender, faith, age, ability or any other form of abuse will be reported to The Football Association for action by that Association. The Isthmian Football League strongly supports the FA statement that there should be a zero tolerance approach against racism and all forms of discrimination. Accordingly any form of discriminatory abuse whether it be based on race or ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender, faith, age, ability or any other form of abuse will be reported to The Football Association for action by that Association. The FA 0800 085 0508 Kick it Out 020 7253 0162 The FA 0800 085 0508 Kick it Out 020 7253 0162 The Isthmian Football League strongly supports the FA statement that there should be a zero tolerance approach against racism and all forms of discrimination. Accordingly any form of discriminatory abuse whether it be based on race or ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender, faith, age, ability or any other form of abuse will be reported to The Football Association for action by that Association. The Isthmian Football League strongly supports the FA statement that there should be a zero tolerance approach against racism and all forms of discrimination. -

Now It's Singing Not Dancing for Daniel

Inside L Leon’s life - 3 Prison tears - 5 City saints - 7 GOOD NEWS Celia’s courage - 8 FOR NORWICH & NORFOLK Christmas 2015: FREE Supplement produced by Celebrate Norwich & Norfolk Now it’s singing not dancing for Daniel Despite recent successful appearances on the hit BBC1 TV show Strictly Come Dancing , Norwich faith world-famous Irish singer Daniel O’Donnell will be sticking to his social action country, folk and Gospel music when he visits Norwich next year. has huge impact Keith Morris reports. I The social action work of churches and faith groups across Norwich is having a huge positive local impact according to the n October, popular entertainer Daniel (53), results of a recently published survey. turned his hand to dancing, accepting an The Cinnamon Faith Action Audit, I invitation to appear on the BBC cult show conducted earlier this year, received Strictly where he was teamed up with Russian responses from 43 Norwich-based faith dancer Kristina Rihanoff. groups. Despite being the third celebrity voted off the Between them these groups reported show, Daniel said he enjoyed the experience: “I running 388 social action projects for the love Strictly, but it's very traumatic waiting to benefit of 85,320 people outside of their own know your fate. Standing at the top of the stairs membership group, during 2014. waiting for the Strictly results to come through This work was done by 215 paid staff and is the worst feeling in the world. Even if it's not 3,921 volunteers, putting in a staggering you that's leaving it's going to be one of your 810,000 hours of work and, using the Living friends, and that's just as difficult.” Wage rate of £7.85 an hour plus some Kristina, his dancing partner, said: “You were additional resources, the financial value of such a joy to work with; you are the most this project work is around £6.7 million. -

Journal) Monday, October 2, 2000 1 Supreme Court of the United States

JNL00$IND1—03-07-02 14:12:04 JNLINDPGT MILES OCTOBER TERM 2000 Reference Index Contents: Page Statistics ....................................................................................... II General .......................................................................................... III Arguments ................................................................................... IV Attorneys ...................................................................................... IV Briefs ............................................................................................. IV Certiorari ..................................................................................... V Judgments, Mandates, and Opinions ....................................... VI Original Cases ............................................................................. VI Parties ........................................................................................... VII Rehearing ..................................................................................... VII Rules ............................................................................................. VII Stays .............................................................................................. VIII Conclusion .................................................................................... VIII (I) JNL00$IND2—03-12-02 20:29:05 JNLINDPGT MILES II STATISTICS AS OF JUNE 29, 2001 In Forma Paid Original Pauperis Total Cases Cases Number of cases on docket.................... -

The Official Matchday Programme of Hornchurch

THE OFFICIAL MATCHDAY PROGRAMME OF HORNCHURCH FOOTBALL CLUB THE URCHIN v LEYTON ORIENT Wednesday 17th July 2019 | Pre Season Friendly | Kick Off 7.45pm | Issue 001 | £2.50 In Loving Memory of Justin Edinburgh and Tina Hunt MAIN CLUB SPONSOR LEAGUE SPONSOR RESPECT STATEMENT 1 TEL: 01708 442145 24 HOUR SERVICE PRE-PAID FUNERAL PLANS PROUD SHIRT SPONSORS OF THE MIGHTY URCHINS 2 INSIDE THIS EDITION HORNCHURCH FOOTBALL CLUB Founded 1923 | Reborn 2005 Address The Stadium, Bridge Avenue, Upminster, Essex, RM14 2LX Telephone: 01708 220080 Website: www.hornchurchfc.com Twitter: @HornchurchFC Joint Owners: Alex Sharp, Laura Purcell, Ken Hunt, Tony Bowditch, Allan Pearce , Richard Hill, Chris Rice Company Registered No. 5438297 07 President TEL: 01708 442145 Del Edkins Life Vice Presidents Mick Baldry, Keith Nichols, Ray Stainer Vice President Fred Hawthorn Chairman 24 HOUR SERVICE Alex Sharp Vice Chairman Colin McBride PRE-PAID FUNERAL PLANS Directors Tony Bowditch, Ken Hunt, Allan Pearce, Wayne Slade, Richard Hill, Chris Rice Committee PROUD SHIRT SPONSORS OF THE MIGHTY URCHINS Laura Purcell, Andy Dickinson, Ken Hunt, Les 04 10 Walker, Sir Gary Hall, Luke Dyerson, Allan Pearce, Colin Burford, Tony Bowditch, Grant Gordon, Jordan Newman, Steve Newman, Colin McBride, Alex Sharp Secretary Norman Posner HTV: Rob Monger Webmaster: Andy Dickinson Programme Editors: Jordan Newman, Andy Dickinson Kit Manager: Dave Holland Facilities: Terry Fisher Stadium PA: Max First Team Manager: Mark Stimson Coaches: Jamie Southon, Tony Gay, Sir Gary Hall (Goalkeeping), Ronnie Hanley, Timi Olomofe Physio Jack Hughes Printers: Design4Print 19 3 FROM THE BOARDROOM ALEX SHARP Good evening everyone and welcome most professional and respectful way. -

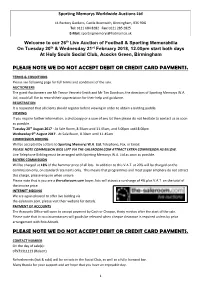

Please Note We Do Not Accept Debit Or Credit Card Payments

Sporting Memorys Worldwide Auctions Ltd 11 Rectory Gardens, Castle Bromwich, Birmingham, B36 9DG Tel: 0121 684 8282 Fax: 0121 285 2825 E-Mail: [email protected] Welcome to our 26th Live Auction of Football & Sporting Memorabilia On Tuesday 20th & Wednesday 21st February 2018, 12.00pm start both days At Holy Souls Social Club, Acocks Green, Birmingham PLEASE NOTE WE DO NOT ACCEPT DEBIT OR CREDIT CARD PAYMENTS. TERMS & CONDITIONS Please see following page for full terms and conditions of the sale. AUCTIONEERS The guest Auctioneers are Mr Trevor Vennett-Smith and Mr Tim Davidson, the directors of Sporting Memorys W.A. Ltd, would all like to record their appreciation for their help and guidance. REGISTRATION It is requested that all clients should register before viewing in order to obtain a bidding paddle. VIEWING If you require further information, a photocopy or a scan of any lot then please do not hesitate to contact us as soon as possible. Tuesday 20th August 2017 - At Sale Room, 8.30am until 11.45am, and 5.00pm until 8.00pm Wednesday 9th August 2017 - At Sale Room, 8.30am until 11.45am COMMISSION BIDDING Will be accepted by Letters to Sporting Memorys W.A. Ltd, Telephone, Fax, or Email. PLEASE NOTE COMMISSION BIDS LEFT VIA THE-SALEROOM.COM ATTRACT EXTRA COMMISSION AS BELOW. Live Telephone Bidding must be arranged with Sporting Memorys W.A. Ltd as soon as possible. BUYERS COMMISSION Will be charged at 18% of the hammer price of all lots. In addition to this V.A.T. at 20% will be charged on the commission only, on standard rate items only.