Cultural Dynamics in National Harmony in South Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sri Lanka Date: 13 January 2013 at 18.00 Hrs

Daily Situation Report - Sri Lanka Date: 13 January 2013 at 18.00 hrs Secretary to H.E. the President Secretary, Ministry of Defence Secretary to the Treasury Secretary, Ministry of Disaster Management Private Secretary to the Hon. Minister of Disaster Management Private Secretary to the Hon. Dy Minister of Disaster Management Affected Deaths Injured Missing Houses Damaged Evacuation Center Province # District Disaster Date D S Division Remarks Families People Reported People People Fully Partially Nos. Families Persons High wind 30.12.2012 Habaraduwa 23 1 Galle Situation normalized Flood 17.12.2012 Tawalama 1 District total 0 0 0 0 0 1 23 0 0 0 Southern Hambantota Flood 11.01.2013 Thissamaharamaya 38 157 1 38 157 2 District total 38 157 0 0 0 0 0 1 38 157 38 157 0 0 0 1 23 1 38 157 Province Total Kegalle Lightning 10.01.2013 Warakapola 4 Electric itetames have been damaged due to the lightning 3 Sa- District total 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 gamuwa Province Total 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 157 Willgamuwa 119 589 10 106 Affected people evacuated to C.C. quartes,Field Officer quarters,Nikolaya child development center,Nikolaya Poruch building,Madawatta poruch building,Maha Saluwakannda State quarters,Pitakannda Community center,Kandanuwara School room,Santha Pitares Rathtota 832 3061 6 9 6 24 94 12 146 505 pre.school,Babaragala Tamil School quartes,Madawatta rabbermala Camp and Dankannda Kataratanna School quartes. Matale 107 463 1 16 90 1 8 30 Affected people evacuated to Kotuwagadara Paddy Store. -

2. Introduction to Kurunegala Area : 2.1 Location and History : 2.2

2. Introduction to Kurunegala Area : 2.1 Location and History : Kurunegala town is the capital of Kurunegala district as well as the capital of North Western Province (Fig 2.1). It has been administered by a Municipal council from as early as 1952 and is yet the only Municipality in the province. It is located at the 98 km post along the Ambepussa - Kurunegala - Trincomalee road in the North - East direction of Colombo. Total area of the district is 4,813 sq. km and this is the third biggest district in Sri Lanka. It is connected with middle hill (Kandy.Matale) in East and low land (Puttalam,Chilaw) of above 100 ft in West. The district is situated 100ft - 500ft above sea level. However to the East of the city it is 500ft - 1000ft. Climate in this district can be classified into three zones. Western and Northern part is in dry zone. Central area is with medium weather and southern zone is with wet weather. Kurunegala had the ancient kingdoms such as Yapahuwa and Panduwasnuwara. Kurunegala is located within the "Coconut Triangle" and most of the service activities related to the coconut plantation sector are located in this town. 2.2 Regional Aspects : Kurunegala is located in North - Western Province and is predominantly an agricultural area. Coconut and paddy are the major agricultural crops. It has access to Northern, Eastern, Central and Western provinces. It is surrounded by Puttalam, Anuradhapura, Matale, Kandy, Kegalle and Gampaha districts. It has a road network connected to many parts of the country.(Fig 2.2) They are, 1. -

Sri Lanka: Elephants, Temples, Spices & Forts 2023

Sri Lanka: Elephants, Temples, Spices & Forts 2023 26 JAN – 14 FEB 2023 Code: 22302 Tour Leaders Em. Prof. Bernard Hoffert Physical Ratings Combining UNESCO World Heritage sites of Anuradhapura, Dambulla, Sigiriya, Polonnaruwa, Kandy and Galle with a number of Sri Lanka's best wildlife sanctuaries including Wilpattu & Yala National Park. Overview Professor Bernard Hoffert, former World President of the International Association of Art-UNESCO (1992-95), leads this cultural tour of Sri Lanka. Visit 6 Cultural UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Sacred City of Anuradhapura – established around a cutting from the 'tree of enlightenment', the Buddha's fig tree, this was the first ancient capital of Sri Lanka. Golden Dambulla Cave Temple – containing magnificent wall paintings and over 150 statues. Ancient City of Sigiriya – a spectacular rock fortress featuring the ancient remains of King Kassapa’s palace from the 5th century AD. The Ancient City of Polonnaruwa – the grand, second capital of Sri Lanka established after the destruction of Anuradhapura in the 1st century. Sacred City of Kandy – capital of Sri Lanka’s hill country and home to the Sacred Tooth Relic of Lord Buddha. Old Town of Galle – this 16th-century Dutch fortified town has ramparts built to protect goods stored by the Dutch East India Company. Visit 4 of Sri Lanka's best Wildlife National Parks: Wilpattu National Park – comprising a series of lakes – or willus – the park is considered the best for viewing the elusive sloth bear and for its population of leopards. Hurulu Eco Park – designated a biosphere reserve in 1977, the area is representative of Sri Lanka's dry-zone dry evergreen forests and is an important habitat for the Sri Lankan elephant. -

EB PMAS Class 2 2011 2.Pdf

EFFICIENCY BAR EXAMINATION FOR OFFICERS IN CLASS II OF PUBLIC MANAGEMENT ASSISTANT'S SERVICE - 2011(II)2013(2014) CENTRAL GOVERNMENT RESULTS OF CANDIDATES No NAME ADDRESS NIC NO INDEX NO SUB1 SUB2 1 COSTA, K.A.G.C. M/Y OF DEFENCE & URBAN DEVELOPMENT, SUPPLY DIVISION, 15/5, 860170337V 10000013 040 057 BALADAKSHA MW, COLOMBO 3. 2 MEDAGODA, G.R.U.K. INLAND REVENUE REGIONAL OFFICE, 334, GALLE ROAD, KALUTARA SOUTH. 745802338V 10000027 --- 024 3 HETTIARACHCHI, H.A.S.W. DEPT. OF EXTERNAL RESOURCES, M/Y OF FINANCE & PLANNING, THE 823273010V 10000030 --- 050 SECRETARIAT, 3RD FLOOR, COLOMBO 1. 4 BANDARA, P.A. 230/4, TEMPLE ROAD, BATAPOLA, MADELGAMUWA, GAMPAHA. 682113260V 10000044 ABS --- 5 PRASANTHIKA, L.G. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATIVE BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM A 858513383V 10000058 040 055 GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 6 ATAPATTU, D.M.D.S. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATION BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM 816130069V 10000061 054 051 A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 7 KUMARIHAMI, W.M.S.N. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ACCOUNTS BRANCH, POB 515, SRI 867010025V 10000075 059 070 CHITTAMPALAM A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 8 JENAT, A.A.D.M. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, NEGOMBO. 685060892V 10000089 034 051 9 GOMES, J.S.T. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA DIVISION, KELANIYA. 846453857V 10000092 031 052 10 HARSHANI, A.I. FINANCE BRANCH, POLICE HEAD QUARTERS, COLOMBO 1. 827122858V 10000104 064 061 11 ABHAYARATHNE, Y.P.J. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA. 841800117V 10000118 049 057 12 WEERAKOON, W.A.D.B. 140/B, THANAYAM PLACE, INGIRIYA. 802893329V 10000121 049 068 13 DE SILVA, W.I. -

Performance Report 2016

Performance Report 2016 (A summery report consisting the performance of the main divisions of the Depart- ment of Archaeology and provincial offices in the year of 2016) Project Operating and Evaluation Division (Planning Division) Department of Archaeology Colombo - 07 Performance Report - 2016 1 Content Page Number 1. Department of Archeology (Vision, Mission and objectives) . 152– 156 2. Investigation and registration division ................................... 157- 165 3. Excavation Division ................................................................... 166 - 172 4. Museum Division ....................................................................... 173 - 175 5. Architectural Conservation Division ...................................... 176 - 181 6. Chemical Conservation Division ............................................. 182 - 185 7. Epigraphy and Numismatics Division .................................... 186 - 188 8. Maintenance Division ............................................................... 189 - 201 9. Promotion Division ................................................................... 202 - 203 10. Accounts Division ...................................................................... 204 - 205 11. Administrative Division ............................................................ 206 - 212 12. Project Operation and Evaluation Division ............................ 213 - 216 13. Legal Division ............................................................................. 217 - 227 Performance Report - 2016 -

North Western Province Rural Roads – Project 5

Involuntary Resettlement Due Diligence Report August 2014 SRI: Integrated Road Investment Program North Western Province Rural Roads – Project 5 Prepared by Road Development Authority, Ministry of Highways, Ports and Shipping for the Asian Development Bank CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 14 May 2014) Currency unit – Sri Lanka rupee (SLRe/SLRs) SLRe 1.00 = $ 0.007669 $1.00 = SLR 130.400 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank AP - Affected Person API - Affected Property Inventory CBO - Community Based Organization CPs - Community Participants CV - Chief Valuer DRR - Due Diligence Report DS - Divisional Secretariat ESDD - Environmental and Social Development Division FGD - Focus Group Discussion GoSL - Government of Sri Lanka GN - Grama Niladari GND - Grama Niladari Division GPS - Global Positioning System GRC - Grievance Redress Committee GRM - Grievance Redress Mechanism INGO - International Non-Government Organizations iROAD - Integrated Road Investment Program IR - Involuntary Resettlement LAA - Land Acquisition Act MOHPS - Ministry of Highways, Ports and Shipping MOU - Memorandum of Understanding MFF - Multi-tranche Financing Facility NGO - Non-Government Organizations NIRP - National Involuntary Resettlement Policy NWP - North Western Province PCC - Project Coordinating Committee PIU - Project Implementing Unit PRA - Participatory Rural Appraisal PS - Pradeshiya Sabha RDA - Road Development Authority SPS - Safeguards Policy Statement This involuntary resettlement due diligence is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

No. 22 National Trust

Quarterly Tours – No. 22 National Trust – Sri Lanka 26th May 2012 Compiled by Nilan Cooray 0 National Trust – Sri Lanka Quarterly Tours – Saturday, 26th May 2012. Programme 0630 hrs. Leave PGIAR 0815 hrs. Comfort stop at Giriulla 0930 hrs Arrive at the estate of Dr. van der Poorten and his wife who will take us round the garden which has been carefully planted with butterfly friendly plants, some of which also encourage birds to feed on the berries, and nest in the trees. 1130 hrs. Leave for Panduwasnuwara, a mediaeval sub- capital of king Parakramabahu I. 1145 hrs. Walk around the site, examine the stone inscription, the rooms in the palace, the fortification and the religious remains 1300 hrs. Adjourn for lunch to the Archaeological Circuit Bungalow. 1345 hrs. Visit the Circular Enclosure thought to be that of Ummadacitta and the Council Chamber of the King. 1415 hrs. Leave for Bingiriya 1500 hrs Drive from Bingiriya to Munneswaram Kovil. 1545 hrs. Munneswaram Kovil - walk round the kovil after a short introduction by an official of the kovil. 1630 hrs. Leave for Riverine Hotel, Waikal along the coast after crossing the Dutch Canal. 1800 hrs. Leave for Colombo 2000hrs. Arrive at the PGIAR (Visit to Panavitiya Ambalama if the time permits) 1 ‘Butterfly Garden’ near Wariyapola Forty acre private estate of Dr. Michael van der Poorten in Hammaliya off Wariyapola has its most stunning feature, a five acre „Butterfly Garden‟. Dr. van der Poorten over the past twenty years has developed part of his coconut estate plantation in to a „wild garden‟, gathering plants which are butterfly friendly, either as food, and host plants for the butterflies, or as food for the larvae. -

Change in Other Field Crop Cultivation in the North Western Province

Change in Other Field Crop Cultivation in the North Western Province Wasanthi Wickramasinghe Research Report No: 160 October 2013 Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Research and Training Institute 114, Wijerama Mawatha Colombo 7 Sri Lanka I First Published: October 2013 © 2013, Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Research and Training Institute Coverpage Designed by: Udeni Karunaratne Final typesetting and lay-out by: Dilanthi Hewavitharana ISBN: 978-955-612-154-4 II FOREWORD Having reached a surplus paddy production in the country from mid 2000, government emphasis was placed on the development of Other Field Crop (OFC) sector to achieve self sufficiency targets of many other crops that can be produced in the country. Nevertheless, the performance of this sector in the recent past had not been promising. Therefore it is necessary to explore issues that are impedimented for the expansion of the OFC sector in Sri Lanka in order to provide some policy direction to the policy makers. A request was also made by the ministry of agriculture to investigate the factors responsible for the backward growth of this sector particularly in the North Western Province (NWP). Considering the necessity, HARTI undertook a study on the changes in other field crop sector in the NW province in 2011. Study identified the main farming system i.e. Chena that had been practiced in the dry zone for many years and supplied bulk of the OFC in the country. This traditional system had evolved into several farming systems in the recent past due to a number of factors. According to the study permanent homesteads cultivating mono-crops without fallowing (Goda hena), irrigated rice fields cultivating OFCs and supplementary irrigated uplands cultivating OFCs are the currently existing farming systems in the province. -

Doubts Fly High Over Overhaul

COVID-19 MT NEW DIAMOND LOCAL CASES TOTAL CASES LEGAL 3,276 IMBROGLIO DEATHS RECOVERED CONTINUES ACTIVE CASES 203 13 3,060 RS. 70.00 PAGES 80 / SECTIONS 7 VOL. 02 – NO. 52 SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, 2020 CASES AROUND THE WORLD RECOVERD TOTAL CASES 22,092,196 RUWAN DOWN TO CRIB TO DEATHS WORK; 20A COMES TO UPDATE CREDIT 30,407,457 951,473 P’MENT THIS WEEK DATA DAILY THE ABOVE STATISTICS ARE CONFIRMED UP UNTIL 6.15 P.M. ON 18 SEPTEMBER 2020 »SEE PAGES 8 & 9 »SEE BUSINESS PAGE 1 »SEE PAGE 5 CENTRAL EXPRESSWAY PROJECT STAGE I Delay costs Govt. Rs. 30 b z Loss mainly due to cost overruns from Section I z Cost increases from $ 158 m to $ 194 m z Govt. blames previous Govt. for Section I delays BY MAHEESHA MUDUGAMUWA The cost overruns have been pace due to the delay in disbursing Meanwhile, the construction of of Highways Johnston Fernando, a calculated based on the price escalations funds of the already signed agreement, Section I of the CEP commenced last proposal has been presented to the The Government will have to absorb billions of rupees as of the construction materials from covering 85% of the contract price, is week. Accordingly, the 37 km stretch Cabinet to construct stretches of roads on additional cost overruns due to the delay in commissioning the date of signing the construction yet to properly begin its construction which was undertaken by Metallurgical the CEP from Pothuhera to Galagedara Section I of the Central Expressway Project (CEP) during the contract agreement to the date when due to the delay on the part of the Corporation of China was scheduled to and Kurunegala to Dambulla. -

Contact Details of Divisional Secretariats Last Update - 2019.03.01

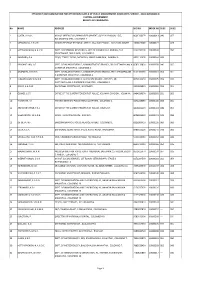

Contact Details of Divisional Secretariats Last Update - 2019.03.01 Divisional Secratariat Divisional Secretary Assistant Divisional Secretary District E-mail Address Divisional Secratariat Address Telephone Number Fax Number Name Telephone Number Mobile Number Name Telephone Number Mobile Number Ampara Ampara [email protected] Addalaichenai Addalaichenai 0672277336 0672279213 J Liyakath Ali 0672055336 0778512717 TJ Athisayaraj 0672277452 0776174102 Divisional Secretariat, Dammarathana Ampara [email protected] Ampara 0632223435 0632223004 N.M.Upeksha Kumari 063-2224595 0702690042 R.Thiraviyaraj 063-2222351 0779597487 Road,Indrasarapura,Ampara Ampara [email protected] Sammanthurai Sammanthurai 0672260236 0672261124 Mr.S.L.Mohamed Haniffa 0672260236 0771098618 Mr.MM.Aseek 0672260293 07684233430 Ampara [email protected] Kalmunai South Divisional Secretariat, Kalmunai 0672229236 0672229380 M.M. Nazeer 0672229236 0772710361 T.J. Athisayaraj 0672224430 0776174102 Ampara [email protected] Padiyathalawa Divisional Secretariat Padiyathalawa 0632246035 0632246190 R.M.N.Wijayathunga 0632246045 0718480734 W.Wimansa Senewirathna 0632050856 0712508960 Ampara [email protected] Sainthamaruthu Main Street Sainthamaruthu 0672221890 0672221890 Nill Nill Nill I.M Rikas 0672056490 0777994493 Ampara [email protected] Dehiattakandiya. Divisional Secretariat, Dehiattakandiya. 027-2250167 027-2250197 Mrs.M.P.W.Shiromani. 027-2250177 0718898478 Mr.S.Partheepan 027-2250081 0714314324 -

No. No. Business Name/Name of the Organization Address Telephone

MANUFACTURE REGISTRATION FOR THE COCONUT RELATED PRODUCTS YEAR - 2017 Business Name/Name of the Telephone No. No. Address E Mail Address Exact location of the Mill organization Number Cn_DC - Desiccated Coconut 1 1 DESICOLANKA(PVT)LTD GANEWATTE 0372264001 / 011 [email protected] GANEWATTE MILLS,NIKADALUPOTHA 2575705 MILLS,NIKADALUPOTHA 2 2 CHILAW D/C AND OIL MILLS PUTTLAM ROAD, THIMBILLA, 322222324 [email protected] PUTTLAM ROAD, THIMBILLA, CHILAW CHILAW 3 3 Rathkarawwa DC & Oil Mills Rathkarawwa,Maspotha 373972143 [email protected] Rathkarawwa,Maspotha 4 4 Marawila CPCS Ltd. Maravila 0322254272,032- [email protected] Maravila 4928842 5 5 Baduwatta Desiccated Coconut Edwin Silva Mawatha,Katana 312241707 [email protected] Edwin Silva Mawatha,Katana Mills(pvt)Ltd 6 6 Madampe Mills (pvt)Ltd 36,Hill street,Dehiwala 777483292 [email protected] Thambagalla, Kakapalliya, Chilaw 7 7 ST.JOSEPH'S DESICCATED COLOMBO ROAD, WATINAPAHA. 112296445 [email protected] COLOMBO ROAD, COCONUT MANUFACTURERS WATINAPAHA, (PVT)LTD 8 8 SIRIYANGANI DESICCATED & FIBRE GIRIULLA ROAD.KATANA. 312240306 [email protected] GIRIULLA ROAD.KATANA. MILLS 9 9 S.A.Silva & Sons Lanka (PVT) LTD Loluwagoda Mills , Loluwa goda 337389376 [email protected] Loluwagoda Mills,Loluwagoda 10 10 ST.Anne s Factory DALUWA,MAMPURI 322269000 [email protected] DALUWA,MAMPURI 11 11 Renuka Agro Exports(pvt)Ltd Pannala Road, Madampe 312261370 [email protected] Pannala Road, Madampe 12 12 Dunagaha Coconut Producers ' Co- Kehelella Factory, Kehelella, 031-2269146, 031- [email protected] Kehelella Factory, Kehelella, Operative Society Badalgama 2246564 Badalgama 13 13 Potthewela DC & Oil Mills (PVT) Ltd No 51/1 , Matha road , Colombo 08 033 2273049 , 077 [email protected] No 51/1 , Matha road , Colombo 7482241 08 14 14 WICHY PLANTATION COMPANY CHILAW RD, KANATHTHEWEWA, 0115629634 / [email protected] CHILAW RD, (PVT)LTD RAMBAWEWA 0372293652 KANATHTHEWEWA, RAMBAWEWA 15 15 J.PM Pinto & Co. -

Some Historical Sites in Sri Lanka – Short Notes Jayaindra Fernando

Some historical sites in Sri Lanka – short notes Jayaindra Fernando Introduction Sri Lanka is a land like no other, with multitude of places to see. If you are over 18 and has not seen these places, then there is no time to lose. If you have children under 18 still there is no time to lose. Show them these cultural gems before they leave the nest to roam the wide geographical and social world on their own. Your country deserves the duty and your Lankan born children are entitled to the privilege. This document is a rough note and not a publication. Distances are as of the original writings and not converted to metric. Of course it is incomplete. All information in this are already in the public domain. Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Anuradhapura and surrounding area ................................................................................................. 3 Sri maha bodi ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Brazen palace ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Ruvanweliseya .................................................................................................................................... 3 Jethawana ..........................................................................................................................................