Frontal-Temporal-Lobe-Epilepsy.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 ILAE Classification & Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes in the Neonate

ILAE Classification & Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes in the Neonate and Infant: Position Statement by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions Authors: Sameer M Zuberi1, Elaine Wirrell2, Elissa Yozawitz3, Jo M Wilmshurst4, Nicola Specchio5, Kate Riney6, Ronit Pressler7, Stephane Auvin8, Pauline Samia9, Edouard Hirsch10, O Carter Snead11, Samuel Wiebe12, J Helen Cross13, Paolo Tinuper14,15, Ingrid E Scheffer16, Rima Nabbout17 1. Paediatric Neurosciences Research Group, Royal Hospital for Children & Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Glasgow, UK. 2. Divisions of Child and Adolescent Neurology and Epilepsy, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, USA. 3. Isabelle Rapin Division of Child Neurology of the Saul R Korey Department of Neurology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY USA. 4. Department of Paediatric Neurology, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 5. Rare and Complex Epilepsy Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Bambino Gesu’ Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Rome, Italy 6. Neurosciences Unit, Queensland Children's Hospital, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia. 7. Clinical Neuroscience, UCL- Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, London, UK. Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE London, UK 8. Université de Paris, AP-HP, Hôpital Robert-Debré, INSERM NeuroDiderot, DMU Innov-RDB, Neurologie Pédiatrique, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Paris, France. 9. Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University, East Africa. 1 10. Neurology Epilepsy Unit “Francis Rohmer”, INSERM 1258, FMTS, Strasbourg University, France. -

Epilepsy Syndromes E9 (1)

EPILEPSY SYNDROMES E9 (1) Epilepsy Syndromes Last updated: September 9, 2021 CLASSIFICATION .......................................................................................................................................... 2 LOCALIZATION-RELATED (FOCAL) EPILEPSY SYNDROMES ........................................................................ 3 TEMPORAL LOBE EPILEPSY (TLE) ............................................................................................................... 3 Epidemiology ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Etiology, Pathology ................................................................................................................................ 3 Clinical Features ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Diagnosis ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Treatment ............................................................................................................................................. 15 EXTRATEMPORAL NEOCORTICAL EPILEPSY ............................................................................................... 16 Etiology ................................................................................................................................................ 16 -

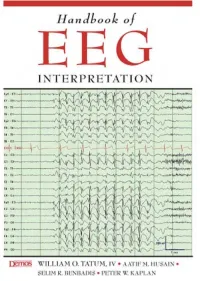

Handbook of EEG INTERPRETATION This Page Intentionally Left Blank Handbook of EEG INTERPRETATION

Handbook of EEG INTERPRETATION This page intentionally left blank Handbook of EEG INTERPRETATION William O. Tatum, IV, DO Section Chief, Department of Neurology, Tampa General Hospital Clinical Professor, Department of Neurology, University of South Florida Tampa, Florida Aatif M. Husain, MD Associate Professor, Department of Medicine (Neurology), Duke University Medical Center Director, Neurodiagnostic Center, Veterans Affairs Medical Center Durham, North Carolina Selim R. Benbadis, MD Director, Comprehensive Epilepsy Program, Tampa General Hospital Professor, Departments of Neurology and Neurosurgery, University of South Florida Tampa, Florida Peter W. Kaplan, MB, FRCP Director, Epilepsy and EEG, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center Professor, Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Baltimore, Maryland Acquisitions Editor: R. Craig Percy Developmental Editor: Richard Johnson Cover Designer: Steve Pisano Indexer: Joann Woy Compositor: Patricia Wallenburg Printer: Victor Graphics Visit our website at www.demosmedpub.com © 2008 Demos Medical Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved. This book is pro- tected by copyright. No part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of EEG interpretation / William O. Tatum IV ... [et al.]. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-933864-11-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-933864-11-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Electroencephalography—Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Tatum, William O. [DNLM: 1. Electroencephalography—methods—Handbooks. WL 39 H23657 2007] RC386.6.E43H36 2007 616.8'047547—dc22 2007022376 Medicine is an ever-changing science undergoing continual development. -

Psychogenic Seizurespsychogenicseizures

PsychogenicPsychogenicSeizuresSeizures MMaartrtiinnSaSalliinsnskykyMM..DD.. PoPortrtllaandndVVAAMMCCEEpipillepsyepsyCCententererooffEExxcecellllenceence OreOreggoonnHeaHealltthh&&SciScienceenceUUninivverersisittyy …You’d better ask the doctors here about my illness, sir. Ask them whether my fit was real or not. TTheheBBrrootthershersKaKararamamazzoovv;;FF..DDooststooevevskskyy,,11888811 Psychogenic Seizures Psychogenic seizures (PNES) PNES in Veterans Treatment and Prognosis *excluding headache, back pain Epilepsy Cases per 100 persons 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.2 1.4 neurologists worldwide* The most common problem faced by 0 1 Epilepsy Neuropathy Cerebrovascular Dementia ~1% of the world burden of disease (WHO) Prevalence (per 100 persons) Murray et al; WHO, 1994Singhai; Arch Neurol 1998 Kobau; MMR, August Medina; 2008 J Neurol Sci 2007 Speaec 08%Sprevalence ~0.85% US prevalence ~0.85%US Disorders that may mimic epilepsy (adults) Cardiovascular events (syncope) » Vasovagal attacks (vasodepressor syncope) » Arrhythmias (Stokes-Adams attacks) Movement disorders » Paroxysmal choreoathetosis » Myoclonus, tics, habit spasms Migraine - confusional, basilar Sleep disorders (parasomnias) Metabolic disorders (hypoglycemia) Psychological disorders » Psychogenic seizures Non-Epileptic Seizures (NES) A transient alteration in behavior resembling an epileptic seizure but not due to paroxysmal neuronal discharges; –Psychogenic Seizures (PNES) without other physiologic abnormalities with probable psychological origin Non-Epileptic Seizures (NES) Seizures Epileptic -

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions N Specchio1, EC Wirrell2*, IE Scheffer3, R Nabbout4, K Riney5, P Samia6, SM Zuberi7, JM Wilmshurst8, E Yozawitz9, R Pressler10, E Hirsch11, S Wiebe12, JH Cross13, P Tinuper14, S Auvin15 1. Rare and Complex Epilepsy Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Bambino Gesu’ Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Rome, Italy 2. Divisions of Child and Adolescent Neurology and Epilepsy, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, USA. 3. University of Melbourne, Austin Health and Royal Children’s Hospital, Florey Institute, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia. 4. Reference Centre for Rare Epilepsies, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Necker–Enfants Malades Hospital, APHP, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Institut Imagine, INSERM, UMR 1163, Université de Paris, Paris, France. 5. Neurosciences Unit, Queensland Children's Hospital, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia. 6. Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University, East Africa. 7. Paediatric Neurosciences Research Group, Royal Hospital for Children & Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Member of European Refence Network EpiCARE, Glasgow, UK. 8. Department of Paediatric Neurology, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 9. Isabelle Rapin Division of Child Neurology of the Saul R Korey Department of Neurology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY USA. 10. Programme of Developmental Neurosciences, UCL NIHR BRC Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, UK 11. -

Epilepsy and Seizure Disorders: a Resource Guide for Parents

$5HVRXUFH *XLGH IRU3DUHQWV www.chadkids.org/epilepsyonline Epilepsy and Seizure Disorder: A Parent Resource Guide ¡ ¡ ¨ © £ ¤ ¢ ¥ ¦ § ¦ ! " $ # ¡ ¨ ' ( £ ¤ ¢ ¥ ¦ %& ¥ - . , ! # ! ) * + * ' - / ! !! ! # ! + ) ' - 00 ! , ! # ! + ) ¡ ¡¡ ¨ ( ( £ ¤ ## ¢ ¥ ¦ % 12 - - 03 ! # # ) * 0 !! ) + 0 , # ! ! ) * + " ' 4 0$ ! ! , # ! + ) 5 8 9 £7 7 162 6 ¦ ¥ 2: ( - 0; ! < - 0> = ? @ 3A ! = ! # 'C B D 3 0 ! ! C D 33 ? ! ! D 3 B ! < 3; = ! # - 3> @ ! ! EF ¤ ¤ 7 ¢ G % H ? 3/ ! ! = C - A I 0 J www.chadkids.org/epilepsyonline Epilepsy and Seizure Disorder: A Parent Resource Guide 2 WWhathat is epilepsy/seizure disorder? 7KHEUDLQFRQWDLQVELOOLRQVRIQHUYHFHOOVFDOOHGQHXURQVWKDWFRPPXQLFDWH HOHFWURQLFDOO\DQGVLJQDOWRHDFKRWKHU$VHL]XUHRFFXUVZKHQWKHUHLVDVXGGHQDQG EULHIH[FHVVVXUJHRIHOHFWULFDODFWLYLW\LQWKHEUDLQEHWZHHQQHUYHFHOOV7KLVFDQ FDXVHDEQRUPDOPRYHPHQWVFKDQJHLQEHKDYLRURUORVVRIFRQVFLRXVQHVV 6HL]XUHVDUHQRWDPHQWDOKHDOWKGLVRUGHU,QVWHDGHSLOHSV\LVDQHXURORJLFDOFRQGLWLRQ WKDWLVVWLOOQRWFRPSOHWHO\XQGHUVWRRG +DYLQJDVLQJOHVHL]XUHGRHVQRWPHDQWKDWDFKLOGKDVHSLOHSV\$FKLOGKDVHSLOHSV\ ZKHQKHRUVKHKDVWZRRUPRUHVHL]XUHVZLWKRXWDFOHDUFDXVHVXFKDVIHYHUKHDG LQMXU\GUXJXVHDOFRKROXVHRUVOHHSGHSULYDWLRQ$ERXWPLOOLRQ$PHULFDQVKDYH HSLOHSV\DQGRIWKHQHZFDVHVWKDWGHYHORSHDFK\HDUXSWR%DUHFKLOGUHQ DQGDGROHVFHQWV,WGHYHORSVLQFKLOGUHQRIDOODJHVDQGFDQDIIHFWWKHPLQGLIIHUHQW -

Mesial Frontal Epilepsy

Epikpsia, 39(Suppl. 4):S49-S61. 1998 Lippincon-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia 0 International League Against Epilepsy Mesial Frontal Epilepsy Norman K. So Oregon Comprehensive Epilepsy Program, Legacy Portland Hospitals, Portland, Oregon, U.S.A. Summary: The mesiofrontal cortex comprises a number of occur. The task of localization of the epileptogenic zone can be distinct anatomic and functional areas. Structural lesions and challenging, whether EEG or imaging methods are used. Suc- cortical dysgenesis are recognized causes of mesial frontal epi- cessful localization can lead to a rewarding outcome after epi- lepsy, but a specific gene defect may also be important, as seen lepsy surgery, particularly in those with an imaged lesion. in some forms of familial frontal lobe epilepsy. The predomi- Key Words: Mesial frontal epilepsy-cingulate gyrus- nant seizure manifestations, which are not necessarily strictly Supplementary motor area-Absence seizure-Hypermotor correlated with a specific ictal onset zone, are absence, hyper- seizure-Postural tonic seizure-Epilepsy surgery. motor, and postural tonic seizures. Other seizure types also FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY convolution. Traditional cytoarchitectonics have further subdivided this anterior frontal region. The frontal pole The frontal lobe is the largest lobe in the brain, ac- refers to the anterior most portion of the frontal lobe, but counting for one-third to one-half of total brain volume there is little consensus on how far back this extends. and weight. On the medial surface, the most important One or more curved.sulci are seen anterior and inferior to landmark is the cingulate sulcus (Fig. 1). This runs as an the cingulate sulcus, called the superior and inferior ros- inverted “C” following the contour of the corpus callo- tral sulci. -

Diagnosis and Management of Epilepsies in Children and Young People 81

81 ���� ������������������������������������������� Diagnosis and management of epilepsies 81 in children and young people A national clinical guideline 1 Introduction 1 2 Diagnosis 3 3 Investigative procedures 6 4 Management 11 5 Antiepileptic drug treatment 15 6 Management of prolonged or serial seizures and convulsive status epilepticus 21 7 Behaviour and learning 23 8 Models of care 25 9 Development of the guideline 27 10 Implementation and audit 31 Annexes 34 Abbreviations 47 References 48 March 2005 COPIES OF ALL SIGN GUIDELINES ARE AVAILABLE ONLINE AT WWW.SIGN.AC.UK KEY TO EVIDENCE STATEMENTS AND GRADES OF RECOMMENDATIONS LEVELS OF EVIDENCE 1++ High quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), or RCTs with a very low risk of bias 1+ Well conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a low risk of bias 1 - Meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a high risk of bias 2++ High quality systematic reviews of case control or cohort studies High quality case control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding or bias and a high probability that the relationship is causal 2+ Well conducted case control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal 2 - Case control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding or bias and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal 3 Non-analytic studies, eg case reports, case series 4 Expert opinion GRADES OF RECOMMENDATION Note: The grade of recommendation relates to the strength of the evidence on which the recommendation is based. -

Treatment for Patients with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome Roundtable

Treatment for Patients with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome Roundtable Video 3/5 – Diagnosis, Issues and Seizures Dr. Randa Jarrar Pediatric Epileptologist at Phoenix Children's Hospital Given the poor prognosis of Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome with regards to seizure control and cognitive outcome, it is very important to apply that term with caution. How do we go about diagnosing it and what kind of investigations do we have to do once we diagnosis it? Well, the diagnosis really relies on that classic triad of many seizure types, mental retardation, and the classic EEG features that we just went over, mainly the slow spike in wave. Some people consider the presence of ten-hertz fast activity as an essential for diagnosis. This can be either associated with atonic seizures or can occur with minimal clinical manifestations, such as apnea or perhaps truncal rigidity, that can be seen mainly during non-REM sleep. As we said, the diagnosis relies heavily on the EEG. Although it sounds easy to diagnosis since you have all these features, the features may not be very clear early at onset. Why? The cause, the history, the seizure types, the EEG features, are not pathognomonic for Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome. They are shared by other epilepsy syndromes and can occur in other seizure types. In addition, the core seizure types may not be present at onset. You can initially have focal seizure or the patient may present with myoclonic seizures, which can complicate the picture. The EEG features we talked about extensively, but I just want to emphasize that a sleep recording is almost essential, not just a sleep recording, but a video sleep recording. -

Epileptic Spasms Are a Feature of DEPDC5 Mtoropathy

Epileptic spasms are a feature of DEPDC5 mTORopathy Gemma L. Carvill, PhD ABSTRACT Douglas E. Crompton, Objective: To assess the presence of DEPDC5 mutations in a cohort of patients with epileptic PhD, MBBS spasms. Brigid M. Regan, BSc Methods: We performed DEPDC5 resequencing in 130 patients with spasms, segregation anal- (Hons) ysis of variants of interest, and detailed clinical assessment of patients with possibly and likely Jacinta M. McMahon, pathogenic variants. BSc (Hons) DEPDC5 Julia Saykally Results: We identified 3 patients with variants in in the cohort of 130 patients with DEPDC5 Matthew Zemel, BS spasms. We also describe 3 additional patients with alterations and epileptic spasms: 2 Amy L. Schneider, MGen from a previously described family and a third ascertained by clinical testing. Overall, we describe DEPDC5 Couns 6 patients from 5 families with spasms and variants; 2 arose de novo and 3 were Leanne Dibbens, PhD familial. Two individuals had focal cortical dysplasia. Clinical outcome was highly variable. Katherine B. Howell, Conclusions: While recent molecular findings in epileptic spasms emphasize the contribution of de MBBS (Hons), novo mutations, we highlight the relevance of inherited mutations in the setting of a family history BMedSc of focal epilepsies. We also illustrate the utility of clinical diagnostic testing and detailed pheno- Simone Mandelstam, typic evaluation in characterizing the constellation of phenotypes associated with DEPDC5 alter- MBChB ations. We expand this phenotypic spectrum to include epileptic spasms, aligning DEPDC5 Richard J. Leventer, epilepsies more with the recognized features of other mTORopathies. Neurol Genet 2015;1:e17; MBBS, PhD doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000016 A. -

Epilepsy in Children – Brain Growth and Behavior

logy & N ro eu u r e o N p h f y o s l i a o l n o r Kanemura and Aihara, J Neurol Neurophysiol 2013, S2 g u y o J Journal of Neurology & Neurophysiology ISSN: 2155-9562 DOI: 10.4172/2155-9562.S2-006 ReviewResearch Article Article OpenOpen Access Access Epilepsy in Children – Brain Growth and Behavior Hideaki Kanemura1* and Masao Aihara2 1Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Yamanashi, Japan 2Interdisciplinary Graduate School of Medicine and Engineering, University of Yamanashi, Japan Abstract The degree of behavioral problems associated with epilepsy in children is greater than would be expected on the basis of the existence of a chronic illness alone. Involvement of the frontal lobe such as atypical evolution of benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BCECTS), epilepsy with continuous spike-waves during slow sleep (CSWS), and frontal lobe epilepsy (FLE) are characterized by impairment of neuropsychological abilities, and are frequently associated with behavioral disorders. In volumetric studies using three-dimensional (3D) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), frontal and prefrontal lobe volumes revealed growth disturbance in patients with atypical evolution of BCECTS, CSWS, and FLE compared with those of normal subjects. These studies also revealed that in patients with shorter seizure durations and abnormal EEG periods, developmental abnormalities of the frontal lobe were soon restored to a more normal growth ratio. Conversely, growth disturbances of the prefrontal lobes were persistent in the patients with longer seizure durations and abnormal EEG periods. These findings suggest that seizure and the duration of paroxysmal anomalies may be associated with prefrontal lobe growth abnormalities, which are associated with neuropsychological problems. -

21543-Non-Epileptic-Seizures-Versus-Frontal-Lobe-Epilepsy-In-An-Adolescent-A-Case-Report.Pdf

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.5732 Non-epileptic Seizures versus Frontal Lobe Epilepsy in an Adolescent: A Case Report Sonia Gaur 1 1. Psychiatry, Stanford University, Stanford, USA Corresponding author: Sonia Gaur, [email protected] Abstract Multiple inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations can be due to system issues, patient complexity, family dynamics, and misdiagnoses to name a few. This study highlights a diagnostically challenging case and how that, in itself, contributed to hospital admissions. Although 18 months elapsed from the time of the initial presentation to the diagnosis of non-epileptic seizures (NES), the suspicion of the diagnosis may have been made earlier by clinicians. The evidence for seizures of post-ictal confusion followed by lethargy, amnesia for the event, and response to an anti-seizure medication only could have provided a higher index of suspicion for NES. Many health care providers will argue that this will create over-diagnoses of NES and usage of anti-epileptic medications. While reviewing the literature on NES, it was noted that frontal lobe epilepsy (FLE) causing psychiatric comorbidities has been poorly studied. Furthermore, this case highlights that within the field of child psychiatry, the same clinical presentation can be interpreted differently. This case helps us understand how eliciting clinical information to enable the timely ordering of imaging could help in diagnoses. This may help set up clinical guidelines for NES for the mental health providers to facilitate improvement in diagnoses and treatment. Categories: Neurology, Pediatrics, Psychiatry Keywords: topiramate, psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, inpatient hospitalization, nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy, vasovagal syncope, adolescent psychiatry, conversion disorder, polypharmacy, electroencephalogram, mri Introduction Non-epileptic seizures (NES) are paroxysmal events with both objective and subjective findings with minimal to absent correlation of electroencephalogram (EEG) findings with the event [1].