Bridging Inner & System Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MDG Report 2010 WINNING the NUMBERS, LOSING the WAR the Other MDG Report 2010

Winning the Numbers, Losing the War: The Other MDG Report 2010 WINNING THE NUMBERS, LOSING THE WAR The Other MDG Report 2010 Copyright © 2010 SOCIAL WATCH PHILIPPINES and UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME (UNDP) All rights reserved Social Watch Philippines and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) encourage the use, translation, adaptation and copying of this material for non-commercial use, with appropriate credit given to Social Watch and UNDP. Inquiries should be addressed to: Social Watch Philippines Room 140, Alumni Center, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, PHILIPPINES 1101 Telefax: +63 02 4366054 Email address: [email protected] Website: http://www.socialwatchphilippines.org The views expressed in this book are those of the authors’ and do not necessarily refl ect the views and policies of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Editorial Board: LEONOR MAGTOLIS BRIONES ISAGANI SERRANO JESSICA CANTOS MARIVIC RAQUIZA RENE RAYA Editorial Team: Editor : ISAGANI SERRANO Copy Editor : SHARON TAYLOR Coordinator : JANET CARANDANG Editorial Assistant : ROJA SALVADOR RESSURECCION BENOZA ERICSON MALONZO Book Design: Cover Design : LEONARD REYES Layout : NANIE GONZALES Photos contributed by: Isagani Serrano, Global Call To Action Against Poverty – Philippines, Medical Action Group, Kaakbay, Alain Pascua, Joe Galvez, Micheal John David, May-I Fabros ACKNOWLEDGEMENT any deserve our thanks for the production of this shadow report. Indeed there are so many of them that Mour attempt to make a list runs the risk of missing names. Social Watch Philippines is particularly grateful to the United Nations Millennium Campaign (UNMC), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Millennium Development Goals Achievement Fund (MDG-F) and the HD2010 Platform for supporting this project with useful advice and funding. -

DOH Presents Agenda for Health Care Financing

Vol. XVII No. 4 July - August 1999 ISSN 0115-9097 DOH presents agenda for health care financing ajor changes in health and local --- spent P34.1 billion or 38.6 the inequities obtaining in the health care financing policies percent while the National Health In- system. “Only those who can afford to are being pursued and surance Program (NHIP) which re- pay are able to support such a system,” Mshall be implemented as placed the Medicare Program spent he said. part of the Department of Health’s P6.4 billion or 7.1 percent. The rest of (DOH) overall effort to reform the the total health expenditure – P7 bil- Second, financing for public health health sector. lion or 8 percent -- came from various programs is subject to the uncertainties of other sources. the annual budget process. Secretary In a roundtable discussion spon- Romualdez pointed out that national sored recently by the DOH and the Based on these figures, one can = 2 Philippine Institute for Development glean some of the problems associated Studies (PIDS), Health Secretary with the manner by which health care Alberto Romualdez expounded on funds are generated. First, the bulk of EDITOR'S NOTES these reforms in his presentation en- the financial burden is on individual fami- titled “An Agenda in Health Care Fi- lies. As Romualdez noted, this leads to For the past couple of years, health nancing for the 21st Century.” Said care financing has been one of the major agenda is being presented to various topics for research and advocacy being sectors for feedback and further refine- WHAT'S INSIDE jointly addressed by the Department of ments. -

20 Century Ends

New Year‟s Celebration 2013 20th CENTURY ENDS ANKIND yesterday stood on the threshold of a new millennium, linked by satellite technology for the most closely watched midnight in history. M The millennium watch was kept all over the world, from a sprinkle of South Pacific islands to the skyscrapers of the Americas, across the pyramids, the Parthenon and the temples of Angkor Wat. Manila Archbishop Luis Antonio Cardinal Tagle said Filipinos should greet 2013 with ''great joy'' and ''anticipation.'' ''The year 2013 is not about Y2K, the end of the world or the biggest party of a lifetime,'' he said. ''It is about J2K13, Jesus 2013, the Jubilee 2013 and Joy to the World 2013. It is about 2013 years of Christ's loving presence in the world.'' The world celebration was tempered, however, by unease over Earth's vulnerability to terrorism and its dependence on computer technology. The excitement was typified by the Pacific archipelago nation of Kiribati, so eager to be first to see the millennium that it actually shifted its portion of the international dateline two hours east. The caution was exemplified by Seattle, which canceled its New Year's party for fear of terrorism. In the Philippines, President Benigno Aquino III is bracing for a “tough” new year. At the same time, he called on Filipinos to pray for global peace and brotherhood and to work as one in facing the challenges of the 21st century. Mr. Estrada and at least one Cabinet official said the impending oil price increase, an expected P60- billion budget deficit, and the public opposition to amending the Constitution to allow unbridled foreign investments would make it a difficult time for the Estrada presidency. -

Governance in Health

3 GOVERNANCE IN HEALTH PEDRITA B. DELA CRUZ I. INTRODUCTION A nation's health does not exist in a vacuum. Today, health is no longer seen from a narrow disease-oriented perspective but recognized as both a means and an end of development. This chapter defines health governance as the ability to harness and mobilize resources to fulfill three fundamental goals: (1) improve the health of the population to help achieve productivity or societal goals; (2) respond to people's expectations; and, (3) provide financial protection against the cost of ill-health. The World Health Organization (WHO) identified these goals as concerns that should drive health systems (World Health Report 2000: 8). The term "resources" covers both material and non-material resources. Material resources include financial, human, facilities, equipment and others. These constitute the "oil" that determines the depth and reach of public health programs or campaigns. Non-material resources, on the other hand, include leadership and management, morale and teamwork, confidence, vision and discipline, creativity and openness, values and culture. They are the "glue" that holds the material resources together, and the "energy" that gives governance ethical direction and momentum. They produce or multiply the material resources. They determine whether these resources are harnessed and maximized or go to waste. Material resources alone are not enough to ensure good health outcomes. Sri Lanka, for example, has a relatively low percentage of GDP devoted to health expenditures but has good health status indicators. India, which has a relatively high percentage of GDP for health expenditures, performs poorly, as measured by health indicators (Figure 1). -

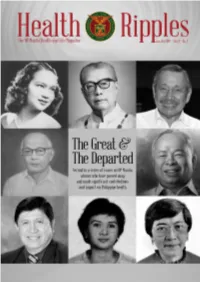

2018 Jan-Jun / Vol. 4 No. 1

The UP Manila Health and Life Magazine i The UP Manila Health Ripples magazine is published bi-annually by the UP Manila Information, Publication, and Public Affairs Office (IPPAO), 8th floor, Philippine General Hospital Central Block, Tel. nos. 554-8400 local 3842. Contributions are welcome. Please email to [email protected] or send to the IPPAO. EDITOR: Cynthia M. Villamor; EDITORIAL CONSULTANT: Dr. Olympia Q. Malanyaon; WRITERS: Cynthia M. Villamor, Fedelynn M. Jemena, January R. Kanindot, Charmaine A. Lingdas; Anne Marie D. Alto LAYOUT ARTIST: Anne Marie D. Alto; PHOTOGRAPHER: Joseph Bautista; CIRCULATION: Sigrid G. Cabiling; Contributing Josephine D. Agapito ii Health Ripples Table of Contents Dr. Florentino B. Herrera, Jr: Humanizing Philippine Medicine 2 Cynthia M. Villamor Dr. Geminiano T. de Ocampo: National Scientist 7 and Father of Modern Philippine Ophthalmology Anne Marie D. Alto Dr. Minda Luz M. Quesada: Passionate Health Champion and Advocate 12 Charmaine A. Lingdas Charlotte A. Floro: Pillar of Rehabilitation Sciences in the Philippines 15 January R. Kanindot Dr. Magdalena C. Cantoria: Advancing Philippine Pharmacy and Botany 19 Fedelynn M. Jemena Dr. Alberto “Quasi” G. Romualdez, Jr.: Crusader for Universal Health Care 22 Charmaine A. Lingdas Dr. Juan M. Flavier: A Doctor for the People 27 Fedelynn M. Jemena Dr. Serafin C. Hilvano: Pillar of Modern Philippine Surgery 32 Cynthia M. Villamor The UP Manila Health and Life Magazine 1 Dr. Florentino B. Herrera, Jr: Humanizing Philippine Medicine By Cynthia M. Villamor “Health must be viewed as both a means to an end and as an end in itself. It is a means insofar as it is a precondition for an individual to harness and maximize his potential as a productive member of the community. -

Reasons Why We Need to Decriminalize Abortion by Clara Rita A

EnGendeRights, Inc. Asserting Gender Equality Reasons Why We Need to Decriminalize Abortion By Clara Rita A. Padilla 1) To save women’s lives and prevent disability from unsafe abortion complications No woman should die or suffer disability from unsafe abortion complications.1 Deaths from unsafe abortion complications are preventable deaths with access to safe abortion2 and post-abortion care. This bill when passed into law will save the lives of thousands of women. The restrictive, colonial, and antiquated 1930 Revised Penal Code abortion law never reduced the number of women inducing abortion. It has only endangered the lives of hundreds of thousands of Filipino women who are forced to undergo unsafe abortion. Prosecution of women who induce abortion and those assisting them is not the answer. Despite the restrictive abortion law and without access to appropriate medical information, supplies and trained health providers, Filipino women, especially poor women with at least three children, have made personal decisions to induce abortion clandestinely and under unsafe conditions risking their lives and health. In 2012 alone, 610,000 Filipino women induced abortion, over 100,000 women were hospitalized, 3 and 1000 women died due to unsafe abortion complications.4 Based on statistics, the number of induced abortions increases proportionately with the increasing Philippine population.5 This 2012 statistics show that lack of access to safe and legal abortion has a grave public health impact on women’s lives and health translating to: • 3 women dying every day from unsafe abortion complications6 • 11 women hospitalized every hour 7 • 70 women induce abortion every hour8 Each year, complications from unsafe abortion is one of the five leading causes of maternal death— between 4.7% – 13.2%—and a leading cause of hospitalization in the Philippines.9 The high number of women dying yearly from complications from unsafe abortion surpass even the number of people who die from dengue. -

Philippine NGO Network Report on the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social,And Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

Philippine NGO Network Report on the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social,and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) 1995 to Present Facilitated by the Philippine Human Rights Information Center (PhilRights), an institution of the Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates (PAHRA) and the Urban Poor Associates (UPA) for the housing section in partnership with 101* non-government organizations, people’s organizations, alliances, and federations based in the Philippines in solidarity with the Center on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE) and Terres des Hommes France (TDHF) (*Please see page iv to vi for the complete list of participating organizations.) ii Table of Contents List of Participating Organizations . p. iv Executive Summary . vii Right to Work . 26 Rights of Migrant Workers . 42 Right to Social Security . 56 Right to Housing . 71 Right to Food . 87 Right to Health . 94 Right to Water . 112 Right to Education . 121 Resource Allocation . 136 iii Participating Organizations Aksiyon Kababaihan ALMANA Alliance of Progressive Labor (APL) Alternate Forum for Research in Mindanao (AFRIM) Aniban ng Manggagawa sa Agrikultura (AMA) Asian South Pacific Bureau of Adult Education - ASPBAE ASSERT Bicol Urban Poor Coordinating Council (BUPCCI) Brethren Inc. Bukluran ng Manggagawang Pilipino (BMP) Center for Migrant Advocacy - Philippines (CMA) Civil Society Network for Education Reforms - E-Net Philippines CO – Multiversity (COM) Commission on Service, Diocese of Malolos Community Organizing for People’s Enterprise (COPE) DPGEA DPRDI Democratic Socialist Women of the Philippines (DSWP) Economic, Social and Cultural Rights-Asia (ESCR-Asia) Education Network – Philippines (E-Net) Families and Relatives of Involuntary Disappearance (FIND) Fellowship of Organizing Endeavors Inc.(FORGE) FIND – SCMR Foodfirst Information Action Network (FIAN-Phils) Freedom from Debt Coalition (FDC) FDC – Cebu FDC – Davao Homenet Philippines Homenet Southeast Asia John J. -

UNIVERSITY of the PHILIPPINES MANILA Taft Avenue, Manila / School of Health Sciences in Leyte, Aurora, So

1 UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES MANILA Taft Avenue, Manila / School of Health Sciences in Leyte, Aurora, So. Cotabato This article first appeared on MALAYA Business Insight (19 Sept. 2013) http://www.malaya.com.ph/business-news/opinion/universal-health-care-pipedream Universal Health Care: A Pipedream? By Alberto Romualdez, M.D. Wednesday, 18 September 2013 ‘Today, halfway through Aquino’s term, health reform advocates are just beginning to realize that attaining universal health care is a long and arduous process.’ “UNIVERSAL HEALTH CARE is the provision to every Filipino of the highest quality of health care that is accessible, efficient, equitably distributed, adequately funded, fairly financed, and appropriately used by an informed and empowered public.” This definition of universal health care was cobbled together by a diverse group of public health experts, economists, clinical specialists, health reform advocates, and health professionals during a workshop in early 2008. The workshop had been organized to review a paper on “The State of the Nation’s Health” to be presented at a panel discussion later in the year as part of the University of the Philippines’ Centennial Celebration. The paper had concluded that the Philippines’ most important health problem was health inequity or the great disparities in access to health care, resulting in significant differences in health status, between the rich minority and the poor majority of Filipinos. The workshop suggested that the definitive solution to this problem was “Universal Health Care”. Many participants had reservations about this suggestion and some even labeled it as a “pipedream”. 2 At that time, the National Health Accounts had reported that, for the year 2006, the country’s total health expenditure (THE) – the amount of money spent by all Filipinos on health goods and services – was around 200 billion pesos, an amount that initially appears to be staggering given the country’s status as a lower middle income nation. -

FOURTH SEMI-ANNUAL UPDATE January 7, 2002

FOURTH SEMI-ANNUAL UPDATE January 7, 2002 – July 6, 2002 POLICY II PROJECT FOURTH SEMI-ANNUAL UPDATE January 7, 2002 – July 6, 2002 Contract No. HRN-C-00-00-00006-00 Submitted to: Policy and Evaluation Division Office of Population U.S. Agency for International Development CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS.....................................................................................................................................v PROJECT OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................1 RESULTS FRAMEWORK........................................................................................................................2 PROJECT RESULTS.................................................................................................................................3 CORE-FUNDED ACTIVITIES...............................................................................................................24 IRs.......................................................................................................................................................24 SSO2 ...................................................................................................................................................32 SSO4 ...................................................................................................................................................33 Quality Assurance...............................................................................................................................33 -

A Legacy Public Health

THE x DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH STORY A Legacyof e Public Health SECOND EDITION 2 Introduction THE Pre-SPANISH ERA ( UNTIL 1565 ) 0 3 This book is dedicated to the women and men of the DOH, whose commitment to the health and well-being of the nation is without parallel. 3 3 THE x DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH STORY A Legacyof e Public Health SECOND EDITION Copyright 2014 Department of Health All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or me- chanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and information system, without the prior written permis- sion of the copyright owner. 2nd Edition Published in the Philippines in 2014 by Cover & Pages Publishing Inc., for the Department of Health, San Lazaro Compound, Tayuman, Manila. ISBN-978-971-784-003-1 Printed in the Philippines 4 Introduction THE Pre-SPANISH ERA ( UNTIL 1565 ) 0 THE x DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH STORY A Legacyof e Public HealthSECOND EDITION 5 THE x DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH STORY A Legacyof e Public Health SECOND EDITION THE x DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH STORY A Legacyof e 6 Public HealthSECOND EDITION Introduction THE Pre-SPANISH ERA ( UNTIL 1565 ) 0 7 THE x DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH STORY A Legacyof e Public Health SECOND EDITION Crispinita A. Valdez OVERALL PROJECT DIRECTOR Charity L. Tan EDITOR Celeste Coscoluella Edgar Ryan Faustino WRITERS Albert Labrador James Ona Edwin Tuyay Ramon Cantonjos Paquito Repelente PHOTOGRAPHERS Mayleen V. Aguirre Aida S. Aracap Rosy Jane Agar-Floro Dr. Aleli Annie Grace P. Sudiacal Mariecar C. -

Coup Attempt

I SPECIAL ISSUE I U.P. ASSESSMENT PROJECT ON THE STATE OF THE NATION THE FAILED DECEMBER COUP View from the UP Community BELINDA A. AQUINO Editor University a/the Philippines Office of the Vice President for Public Affairs in co,yunction with Center for Integrative and Development Studies Diliman, Quezon City Maren 1990 About the Center For Integretlve end Development Studies The UP Center for Integrative and Development Studies (UP-CIOS) was established In September t 985 to promote Interdisciplinary and Integrative studies on crttical topics bearing on development policies Contents and Issues. These studies should address slgnfficant concems 01 Philippine society In that they deal wnh problems whose under t standing and resolution have Important Implications for the well-being 01 major sectors 01 the country. The Center seeks to initiate and support broad research topics that 'ntroductlon call for Innovative methodological approaches and muni-disclplinary collaboration. While public policy questions are the primary concern of lIP-CIOS, n also encourages basic research that Is neededtoInform Intelligently the direction and substance of policy-oriented research. T~e Failed Coup and the Politics of 1 I Violence The Center functions under the Office of the UP President, currently Prof. Jose V. Abueva. For further Information, contact: Dr. C.rolln. O. By Belinda A. Aquino, Vice-Presidenf for Public A!fal~s and Pr?fes~orofPolitical Science and Hem.ndez, Director, UP-CIDS, PeED Hoefer, UP Dlllmen, Quezon City. Tel. N~. I PUblic Admmlstratlon, University ofthe 17-3540, 99-9691 and 97-6061 I~I 518. I Phlllppmes 1 AbDut the National Assessment Project ,! Part ONE The National Assessment Project was launched underUP President I, Jose V. -

ICP PHC 001 19791027 Eng.Pdf (4.523Mo)

ICpipHC!OOl ?1 .January 1980 • • n('IERREGIONAL WORKSHOP ON THE DEVE~MENT OF HEALTH 'IEAMS IN RURAL WORK Convened by the •• WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION REGIONAL OFFICE r'OR THE WES'IERN PACIFIC , . Tacloban City, Philippines 22-27 October 1979 FINAL REPORT Not for sale Printed and distributed by the WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific Manila, Philippines January 1980 NOTE The views expressed in this report are those of the participants in the Workshop and do not necessarily reflect th~ policy of the World Health Organization. • • ... This report was prepared by the World Health Organization r, Regional Office for the Western Pacific for Governments of Member states in the Region and for participants in the Interregional Workshop on the Development of Health Teams in Rural Work, held in Tacloban City, Philippines, from 22-27 October 1979. 1 1. SUMMARY The general objective of the Workshop was to share experiences and stimulate action on the part of WHO Member States in the training and utilization of health teams for rural development. Visits were conducted to two field projects in Leyte to provide common field experience in primary health care and serve as points of reference in group discussions, taking into consideration the 10 recommendations contained in the publication, Training and utilization of auxiliary personnel for rural health teams in developing countries: Report of a WHO Expert Committeel • Criteria and indicators were evolved for each recommendation and, together with orientation on technology in educational planning and management, these served as bases for the development of specific country action plans by the participants.