Governing Social Security: Economic Crisis and Reform in Indonesia, The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hbeat60a.Pdf

2 HEALTHbeat I July - August 2010 HEALTH exam eeny, meeny, miney, mo... _____ 1. President Noynoy Aquino’s platform on health is called... a) Primary Health Care b) Universal Health Care c) Well Family Health Care _____ 2. Dengue in its most severe form is called... a) dengue fever b) dengue hemorrhagic fever c) dengue shock syndrome _____ 3. Psoriasis is... a) an autoimmune disease b) a communicable disease c) a skin disease _____ 4. Disfigurement and disability from Filariasis is due to... a) mosquitoes b) snails c) worms _____ 5. A temporary family planning method based on the natural effect of exclusive breastfeeding is... a) Depo-Provera b) Lactational Amenorrhea c) Tubal Ligation _____ 6. The creamy yellow or golden substance that is present in the breasts before the mature milk is made is... a) Colostrum b) Oxytocin c) Prolactin _____ 7. The pop culture among the youth that rampantly express depressing words through music, visual arts and the Internet is called... a) EMO b) Jejemon c) Badingo _____ 8. The greatest risk factor for developing lung cancer is... a) Human Papilloma Virus b) Fats c) Smoking _____ 9. In an effort to further improve health services to the people and be at par with its private counterparts, Secretary Enrique T. Ona wants the DOH Central Office and two or three pilot DOH hospitals to get the international standard called... a) ICD 10 b) ISO Certification c) PS Mark _____ 10. PhilHealth’s minimum annual contribution is worth... a) Php 300 b) Php 600 c) Php 1,200 Answers on Page 49 July - August 2010 I HEALTHbeat 3 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH - National Center for Health Promotion 2F Bldg. -

MDG Report 2010 WINNING the NUMBERS, LOSING the WAR the Other MDG Report 2010

Winning the Numbers, Losing the War: The Other MDG Report 2010 WINNING THE NUMBERS, LOSING THE WAR The Other MDG Report 2010 Copyright © 2010 SOCIAL WATCH PHILIPPINES and UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME (UNDP) All rights reserved Social Watch Philippines and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) encourage the use, translation, adaptation and copying of this material for non-commercial use, with appropriate credit given to Social Watch and UNDP. Inquiries should be addressed to: Social Watch Philippines Room 140, Alumni Center, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, PHILIPPINES 1101 Telefax: +63 02 4366054 Email address: [email protected] Website: http://www.socialwatchphilippines.org The views expressed in this book are those of the authors’ and do not necessarily refl ect the views and policies of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Editorial Board: LEONOR MAGTOLIS BRIONES ISAGANI SERRANO JESSICA CANTOS MARIVIC RAQUIZA RENE RAYA Editorial Team: Editor : ISAGANI SERRANO Copy Editor : SHARON TAYLOR Coordinator : JANET CARANDANG Editorial Assistant : ROJA SALVADOR RESSURECCION BENOZA ERICSON MALONZO Book Design: Cover Design : LEONARD REYES Layout : NANIE GONZALES Photos contributed by: Isagani Serrano, Global Call To Action Against Poverty – Philippines, Medical Action Group, Kaakbay, Alain Pascua, Joe Galvez, Micheal John David, May-I Fabros ACKNOWLEDGEMENT any deserve our thanks for the production of this shadow report. Indeed there are so many of them that Mour attempt to make a list runs the risk of missing names. Social Watch Philippines is particularly grateful to the United Nations Millennium Campaign (UNMC), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Millennium Development Goals Achievement Fund (MDG-F) and the HD2010 Platform for supporting this project with useful advice and funding. -

Between Rhetoric and Reality: the Progress of Reforms Under the Benigno S. Aquino Administration

Acknowledgement I would like to extend my deepest gratitude, first, to the Institute of Developing Economies-JETRO, for having given me six months from September, 2011 to review, reflect and record my findings on the concern of the study. IDE-JETRO has been a most ideal site for this endeavor and I express my thanks for Executive Vice President Toyojiro Maruya and the Director of the International Exchange and Training Department, Mr. Hiroshi Sato. At IDE, I had many opportunities to exchange views as well as pleasantries with my counterpart, Takeshi Kawanaka. I thank Dr. Kawanaka for the constant support throughout the duration of my fellowship. My stay in IDE has also been facilitated by the continuous assistance of the “dynamic duo” of Takao Tsuneishi and Kenji Murasaki. The level of responsiveness of these two, from the days when we were corresponding before my arrival in Japan to the last days of my stay in IDE, is beyond compare. I have also had the opportunity to build friendships with IDE Researchers, from Nobuhiro Aizawa who I met in another part of the world two in 2009, to Izumi Chibana, one of three people that I could talk to in Filipino, the other two being Takeshi and IDE Researcher, Velle Atienza. Maraming salamat sa inyo! I have also enjoyed the company of a number of other IDE researchers within or beyond the confines of the Institute—Khoo Boo Teik, Kaoru Murakami, Hiroshi Kuwamori, and Sanae Suzuki. I have been privilege to meet researchers from other disciplines or area studies, Masashi Nakamura, Kozo Kunimune, Tatsufumi Yamagata, Yasushi Hazama, Housan Darwisha, Shozo Sakata, Tomohiro Machikita, Kenmei Tsubota, Ryoichi Hisasue, Hitoshi Suzuki, Shinichi Shigetomi, and Tsuruyo Funatsu. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science Hegemony

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Theses Online The London School of Economics and Political Science Hegemony, Transformism and Anti-Politics: Community-Driven Development Programmes at the World Bank Emmanuelle Poncin A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. London, June 2012. 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,559 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Patrick Murphy and Madeleine Poncin. 2 Abstract This thesis scrutinises the emergence, expansion, operations and effects of community-driven development (CDD) programmes, referring to the most popular and ambitious form of local, participatory development promoted by the World Bank. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

The Role of Local Leadership in Village Governance

3009 Talent Development & Excellence Vol.12, No.3s, 2020, 3009 – 3020 A Study of Leadership in the Management of Village Development Program: The Role of Local Leadership in Village Governance Kushandajani1,*, Teguh Yuwono2, Fitriyah2 1 Department of Politics and Government, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Diponegoro, Tembalang, Semarang, Jawa Tengah 50271, Indonesia email: [email protected] 2 Department of Politics and Government, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Diponegoro, Tembalang, Semarang, Jawa Tengah 50271, Indonesia Abstract: Policies regarding villages in Indonesia have a strong impact on village governance. Indonesian Law No. 6/2014 recognizes that the “Village has the rights of origin and traditional rights to regulate and manage the interests of the local community.” Through this authority, the village seeks to manage development programs that demand a prominent leadership role for the village leader. For that reason, the research sought to describe the expectations of the village head and measure the reality of their leadership role in managing the development programs in his village. Using a mixed method combining in-depth interview techniques and surveys of some 201 respondents, this research resulted in several important findings. First, Lurah as a village leader was able to formulate the plan very well through the involvement of all village actors. Second, Lurah maintained a strong level of leadership at the program implementation stage, through techniques that built mutual awareness of the importance of village development programs that had been jointly initiated. Keywords: local leadership, village governance, program management I. INTRODUCTION In the hierarchical system of government in Indonesia, the desa (village) is located below the kecamatan (district). -

DOH Presents Agenda for Health Care Financing

Vol. XVII No. 4 July - August 1999 ISSN 0115-9097 DOH presents agenda for health care financing ajor changes in health and local --- spent P34.1 billion or 38.6 the inequities obtaining in the health care financing policies percent while the National Health In- system. “Only those who can afford to are being pursued and surance Program (NHIP) which re- pay are able to support such a system,” Mshall be implemented as placed the Medicare Program spent he said. part of the Department of Health’s P6.4 billion or 7.1 percent. The rest of (DOH) overall effort to reform the the total health expenditure – P7 bil- Second, financing for public health health sector. lion or 8 percent -- came from various programs is subject to the uncertainties of other sources. the annual budget process. Secretary In a roundtable discussion spon- Romualdez pointed out that national sored recently by the DOH and the Based on these figures, one can = 2 Philippine Institute for Development glean some of the problems associated Studies (PIDS), Health Secretary with the manner by which health care Alberto Romualdez expounded on funds are generated. First, the bulk of EDITOR'S NOTES these reforms in his presentation en- the financial burden is on individual fami- titled “An Agenda in Health Care Fi- lies. As Romualdez noted, this leads to For the past couple of years, health nancing for the 21st Century.” Said care financing has been one of the major agenda is being presented to various topics for research and advocacy being sectors for feedback and further refine- WHAT'S INSIDE jointly addressed by the Department of ments. -

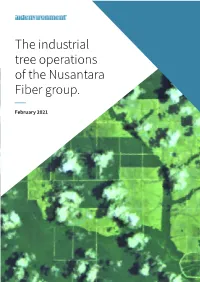

The Industrial Tree Operations of the Nusantara Fiber Group

The industrial tree operations of the Nusantara Fiber group. February 2021 Colofon The industrial tree operations of the Nusantara Fiber group This report is part of the project 'Corporate Transformation in Indonesia's Pulp & Paper Sector' Supported by Good Energies Foundation www.goodenergies.org February 2021 Contact: www.aidenvironment.org/pulpandpaper/ [email protected] Front page image: Forest clearing by Nusantara Fiber's plantation company PT Industrial Forest Plantation Landsat 8 satellite image, early October 2020 Images: Images of Industrial Forest Plantations used in the report were taken with the support of Earth Equalizer www.facebook.com/earthqualizerofficial/ Graphic Design: Grace Cunningham www.linkedin.com/in/gracecunninghamdesign/ Aidenvironment Barentszplein 7 1013 NJ Amsterdam The Netherlands + 31 (0)20 686 81 11 www.aidenvironment.org [email protected] Aidenvironment is registered at the Chamber of Commerce of Amsterdam in the Netherlands, number 41208024 Contents The industrial tree operations of the Nusantara Fiber group | Aidenvironment Executive summary p. 6 Conclusions and recommendations p. 8 Introduction p. 11 CHAPTER ONE Company profile 1 Nusantara Fiber group: company profile p. 12 1.1 Industrial tree concessions p. 13 1.2 Company structure p. 14 CHAPTER TWO Deforestation 2 Deforestration by the Nusantara Fiber group p. 16 for industrial 2.1 Forest loss of 26,000 hectares since 2016 p. 18 trees 2.2 PT Industrial Forest Plantation p. 20 2.3 PT Santan Borneo Abadi p. 22 2.4 PT Mahakam Persada Sakti p. 25 2.5 PT Bakayan Jaya Abadi p.26 2.6 PT Permata Hijau Khatulistiwa p.27 CHAPTER THREE Palm oil 3 The palm oil businesses of Nusantara Fiber directors p. -

The Anti Money Laundering Approach

Center for International Forestry Research Center for International Forestry Research CIFOR Occasional Paper publishes the results of research that is particularly significant to tropical forestry. The content of each paper is peer reviewed internally and externally, and published simultaneously on the web in downloadable format (www.cifor.cgiar.org/publications/papers). Contact publications at [email protected] to request a copy. CIFOR Occasional Paper No. 44 Fighting forest crime and promoting prudent banking for sustainable forest management The Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) is a leading international forestry The anti money laundering approach research organization established in 1993 in response to global concerns about the social, environmental, and economic consequences of forest loss and degradation. CIFOR is dedicated to developing policies and technologies for sustainable use and management of forests, and for enhancing the well-being of people in developing countries who rely on tropical forests for their livelihoods. CIFOR is one of the 15 Future Harvest centres of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). With headquarters in Bogor, Indonesia, CIFOR has regional offices in Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cameroon and Zimbabwe, and it works in over 30 other countries around the world. Bambang Setiono and Yunus Husein CIFOR is one of the 15 Future Harvest centres CIFOR of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) Donors CIFOR Occasional Paper Series The Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) receives its major funding from governments, international development organizations, private 1. Forestry Research within the Consultative Group on International 23. Les Approches Participatives dans la Gestion des Ecosystemes Forestiers foundations and regional organizations. -

Giving Report 2010/2011 Report Giving

Medicine Engineering Public Policy Music Business Law Arts and Social Sciences National University Singapore of GIVING REPORT 2010/2011 GIVING REPORT DEVELOPMENT OFFICE National University of Singapore Shaw Foundation Alumni House 2010/2011 #03-01, 11 Kent Ridge Drive Singapore 119244 t: +65 6516 8000 / 1-800-DEVELOP f: +65 6775 9161 e: [email protected] www.giving.nus.edu.sg PRESIDENT’S STATEMENT Dear alumni and friends, Your support this past year has provided countless opportunities for the National Science University of Singapore (NUS), particularly From music to for the students who are at the heart of our University. For example, approximately medicine, your 1,700 students received bursaries. Around 1,400 of these were partially supported by gift today makes the Annual Giving campaign and about 300 are Named Bursaries. Thank you for Computing a difference to a making this possible. student’s tomorrow Our future is very exciting. NUS University Town will open its doors in the coming months and the Yale-NUS College will follow a few years later. These new President’s Statement........................................... 01 initiatives will allow NUS to continue pursuing its goal of offering students, Thank You For Your Contribution.................... 02 from the entire NUS campus, a broader Education { 02 } education that will challenge them and Research { 06 } position them well for the future. Service { 10 } Design and Environment Through these and other innovations, Annual Giving – NUS is also breaking new ground in Making A Difference Together......................... 14 higher education, both in Singapore and the region. The NUS experience will Strength In Numbers............................................ -

World Bank Document

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: PAD2539 Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED LOAN Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF $100 MILLION TO THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA Public Disclosure Authorized FOR A IMPROVEMENT OF SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT TO SUPPORT REGIONAL AND METROPOLITAN CITIES November 7, 2019 Environment & Natural Resources Global Practice East Asia And Pacific Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective October 31, 2019) Currency Unit = USD IDR 14,008 = US$1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 Regional Vice President: Victoria Kwakwa Country Director: Rodrigo A. Chaves Senior Global Practice Director: Karin Erika Kemper Practice Manager: Ann Jeanette Glauber Task Team Leader(s): Frank Van Woerden ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AMDAL Analisis Mengenai Dampak Lingkungan (environmental impact assessment) APBD Anggaran Pendapatan, dan Belanja Daerah (local government budget) APBN Anggaran Pendapatan dan Belanja Negara (national government budget) BAPPEDA Municipal Development Planning Agency Bappenas Ministry of National Development Planning BLUD Badan Layanan Umum Daerah (public service unit) CDM Clean Development Mechanism CHS Complaint Handling System Coordinating Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Investment -

Ng Teng Fong Family — Far East Organization & Sino Group

28 JULY 2014 Ng Teng Fong Family — Far East Organization & Sino Group Founders of Singapore-based developer Far East Organization and Hong Kong-based developer Sino Group Speculative trading by Robert Ng contributed to the collapse of the Hong Kong Futures Exchange in 1987. He was investigated but not prosecuted. The family has close ties to the governments of Singapore, Hong Kong and China. Capital Profile covers 12 family members and 24 companies Ilya Garger INTRODUCTION Editor in Chief [email protected] Brothers Robert Ng Chee Siong and Philip Ng ued at over USD 45bn, according to the Sze Toh Yuin Munn Chee Tat control Far East Organziation (FEO), group website. Forbes estimates Robert and Research Editor Singapore's largest property developer, and Philip Ng's total net worth as of 2014 at USD [email protected] Sino Group, a major developer in Hong Kong. 12.4bn, making the family Singapore's rich- est. David Wu They inherited the business from their father Researcher Ng Teng Fong, who founded FEO in 1960 and [email protected] Sino Group a decade later. Ng Teng Fong, Family who died in 2010, immigrated to Singapore Jacob Li from China's Fujian province in the 1930s. Ng Teng Fong died in 2010 at the age of 82 Analyst and was survived by wife Tan Kim Choo, his [email protected] Robert Ng, the eldest son of Ng Teng Fong, is two sons, five daughters, 22 grandchildren and one great-grandson, according to an Jessica Kurnia based in Hong Kong and chairs Sino Group.